My quick post on Saturday, in response to someone’s comment, was designed simply to illustrate what should have been quite an obvious point: looking across countries in any particular year, countries with large populations don’t tend to be richer (per capita GDP) than countries with small populations. Just among the very big countries, the United States is towards the top of the GDP per capita rankings (beaten by a bunch of small countries), and China, India, Indonesia, Pakistan, and Brazil are not. Since both the physical sizes of countries, and their populations, are the outcomes of all sorts of historical factors, it wasn’t an observation about immigration policy or (wince) “population policy”. And, of course, GDP per capita isn’t everything: moderately well-off large countries are typically more powerful (defence or offence) than small rich ones.

But, continuing to play with the same data download from the IMF WEO database (190 or so countries and territories) for the period since 1995, is there any obvious relationship betweeen population growth rates, and growth in real per capita GDP?

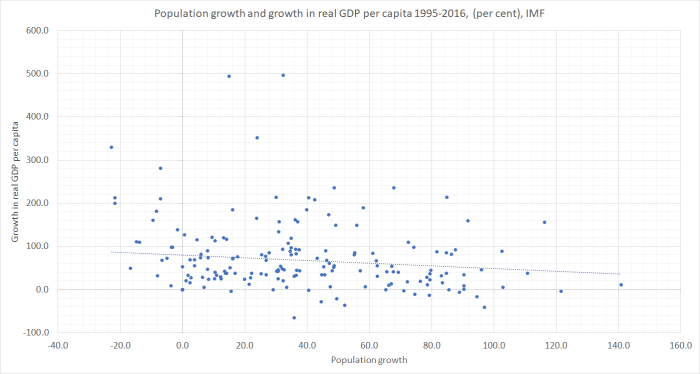

Here is the chart

Actually, I’ve left out three extreme outliers – all oil producers. Equatorial Guinea had growth in real GDP per capita of about 2500 per cent over the period, and UAE and Qatar had population growth of 300-400 per cent (in one case, with falling real GDP per capita, and in the other with a moderate increase).

There is basically no relationship between the two series – again, each dot is a country. The simple linear regression line is downward-sloping but that probably wouldn’t be a statistically significant relationship. Bear in mind though that simply charting population growth and per capita GDP growth for the same period could have shown an upward-sloping relationship even if there was no causal link from faster population growth to faster per capita economic growth: countries with rapid growth in real GDP per capita might be expected to attract more people (immigrants flow towards opportunity) and perhaps even induce higher birth rates. But there is no sign of even that sort of relationship, across all countries, and over this period of 20 years or so (this sort of reverse causality is a big problem looking at annual data, but much less so looking at long periods).

The full sample of countries includes a huge range of types of countries – from war-torn poverty stricken basket cases (Syria, Somalia, Afghanistan) to tiny remote islands (Tuvalu), as well as places with strong institutions, good connections, and an established record of economic performance. How do this simple bivariate relationships look if we focus just on these latter countries?

In various posts over the years, I’ve used a sample of about 40 fairly advanced countries, encompassing the members of the OECD and the EU, as well as Taiwan and Singapore. There is still a lot of difference among these countries: places that were non-market communist economies only 30 years ago, the odd place (eg Mexico) that is more like an honorary member of the group of advanced countries, as well as the places with very high productivity (France, Germany, United States, Ireland, Norway). And there are countries as small as Malta or Luxembourg, and as large as the United States. This group leaves out countries that appear to be rich only because of oil.

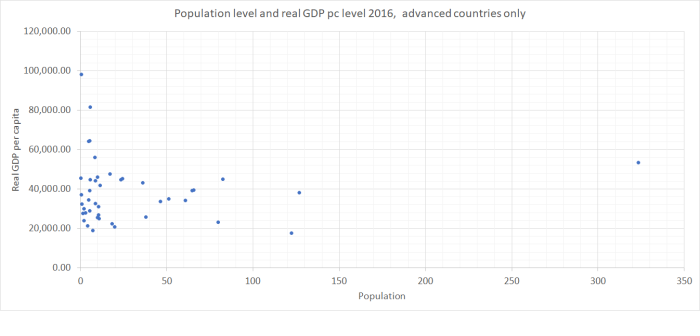

Here is the simplest plot: of the levels of population and GDP per capita in 2016.

This time, the simple regression line is very slightly upward sloping. Remove the US and it changes sign. Remove all the countries with more than 50 million population and it is still downward sloping.

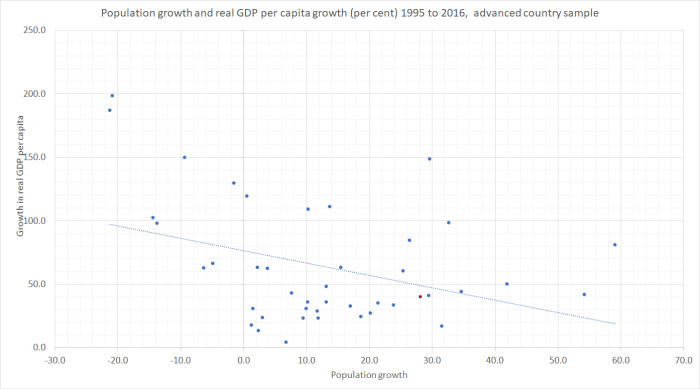

But what about growth rates? For quite a few of these countries, GDP per capita is pretty shaky before about 1995 (communist-era and immediate post-communist transition). That’s why I’ve done all these charts for just the last 20 years or so. But that also happens to be a period when there has been a lot more population movement between advanced countries (especially in Europe).

Recall that even if there was no causal relationship running from population growth to growth in real GDP per capita, there was a possibility that we might have seen an upward-sloping relationship simply from any link between successful economies drawing in more people (as happened in Ireland most obviously – net immigration rising well after the boom in per capita GDP and productivity). But, in fact, across these 40 or so advanced countries, any relationship is downward sloping. Across these countries in this period, faster population growth has been associated with slower real per capita GDP growth. (For the eagle-eyed among you, New Zealand is the red dot.)

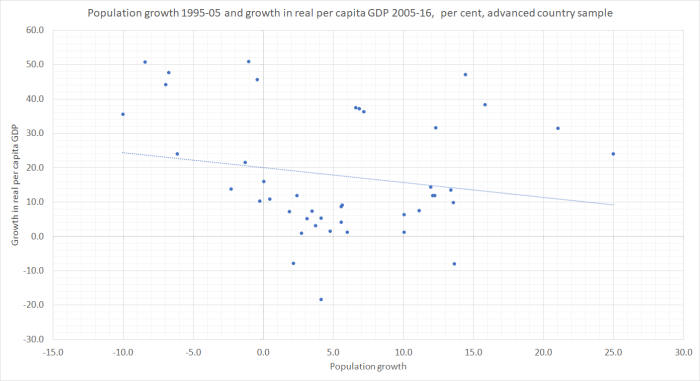

And in this final chart, I’ve broken the period in two. I’ve charted, for each country, population growth in the first 10 years of the period (1995 to 2005) against real GDP per capita in the second half of the period (2005 to 2016). In other words, none of the population growth variable is directly caused by the growth in the real per capita GDP variable.

The downward-sloping relationships is weaker this time – less of the variance in GDP growth is explained simply by prior population growth – but again it is downward-sloping, and not the upward-sloping line many of the immigration-policy boosters in New Zealand would like us to believe. I forgot to mark New Zealand on this chart – we are one of the dots a bit below the line with 12 per cent population growth – but there is nothing unusual about New Zealand’s place on either chart.

If one wants to get more sophisticated, one could look at growth in labour productivity or total factor productivity, rather than just real GDP per capita. Especially for TFP, one becomes dependent on the model used in estimating TFP and the available sample of countries drops away, As for labour productivity, in earlier posts I’ve illustrated the lack of a positive relationship between population growth and productivity growth (and recall that New Zealand has managed better real per capita GDP growth than productivity growth, by working longer hours), and that – for example – if anything business investment as a share of GDP has been negatively correlated with population growth across advanced countries. That is the opposite of what might been expected if population growth – and immigration – was typically boosting the productivity and per capita income prospects of recipient countries.

It is past time we started backing our own people, not looking to replace or augment them with a mythical group from across the water. Part of that involves the government getting serious about facing up to the disappointing economic outcomes of our long-running Think Big economic and social experiment with large scale immigration. As part of that, in turn, a serious review of immigration policy by the Productivity Commission – there have been two in Australia in the last 15 years – would be a good place to start.

Number of people doesn’t change amount of natural/primary resources. This might explain the consistent slight downward slope to some extent.

Or maybe there are multiple factors mostly cancelling each other out, or maybe there is no effect at all and it’s just noise.

LikeLike

NZ Productivity Commission

We recommend you

Agree/disagree

b agree that Commission’s second tranche of inquiries be selected on the degree that

they:

• are relatively uncontroversial given the desire to establish broad political support for the Commission

Click to access t2011-2000.pdf

LikeLike

That was a pragmatic recommendation at the time, but the PC now seems more securely established than it was in 2011.

LikeLike

It is strange that the Australian PC tackled the issue. Maybe our elites were fore warned (is what I think)?

LikeLike

“”review of immigration policy by the Productivity Commission – there have been two in Australia in the last 15 years”” – what were their conclusions? Doesn’t seem to have changed their immigration policies nor the number of Kiwis moving to Australia.

LikeLike

In a study for the Government in 2006, the Productivity Commission modelled a 50 per cent increase in the skilled migration program (an increase that eventuated in subsequent years.) That substantial increase in skilled migration was projected to yield an estimated gain in annual per capita income of just 0.7 per cent ($320) and only after 20 years. It was swamped by other, domestic drivers of productivity growth. Moreover, most of the aggregate gain accrued to migrants themselves — the average incomes of the population existing in ‘year zero’ actually declined slightly.

From Introduction

http://www.pc.gov.au/research/supporting/sustainable-population

Oliver Hartwich smells money (?) in multiculturalism [Chapter 11]

LikeLike

Sorethumb: Just read that chapter 12. In general it seems sensible to me. In summary immigration can work if selecting genuine skilled workers and fails when selecting low-paid. The welfare state encourages the low paid, low skilled and their families to stay on as dependents when they are no longer needed. In UK and in Germany failure to plan and think through immigration has led to significant problems.

So if Mr Lees-Galloway is reading this:

. stop low paid immigration – both for residency and for extended work visas

. think about what you are doing and where it is leading

Minor objection: the idea that 50,000 Huguenots arriving over a period of a century is somehow comparable to 7 million immigrants arriving since 1950 shows the author has little concept of maths.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well if you go back even further then you would have NZ migrants at 80% of the population. The current migrant level at 26% of the population is actually considered very low given our migrant intensive history.

LikeLike

Yes, that sounds like a fair summary. And individual country circumstances may matter: for a country near the centre of things, no longer much reliant on natural resources immigration is more likely to be economically beneficial all round than in a remote place primarily flourishing by natural resources. To shift the focus off nz one could think of Belgium or Denmark on the one hand and Australia on the other.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I heard Mathew Hooten on RNZ. He said a tram line down Dominion Road won’t fix anything. Labour made a fuss about Chinese sounding names and NZ First is (supposedly) opposed to immigration. Yet it is as strong as ever.

…

The Herald has an item about Invercargills first mosque and it’s Iman (a Harley riding dairy farmer). The question being how tolerant are the people of Invercargill? After all there is an unwritten law being violated here the logic of which is long forgotten? . My friend was in Invercargil recently with his little daughter and remarked on what a great place it was for children. Eg kids hide coloured stones with numbers on and post on social media ; other kids find them and hide them again.

LikeLike

Does leverage and debt effect the amount of immigrants we let in?

LikeLike

Business Credit Agency Moody’s “We assess New Zealand’s fiscal strength as Very High (+)”

Moody’s gives a nod to the Government’s fiscal responsibility rules – keeping Core Crown spending at roughly 30% of GDP and to reduce public debt to 20% of GDP by 2021/2022.

New Zealand’s economic strength is also “Very High (-)”.

“New Zealand’s economy has shown faster GDP growth than other Aaa-rated sovereigns in the past five years, which counterbalances its economic weaknesses,”

LikeLiked by 1 person

If the population ponzi stopped it wouldn’t look so good?

LikeLike

Informative charts. Despite all the evidence that our current turbo-charged immigration policy hasn’t delivered economically, it is still full speed ahead. Not sure why exactly. Maybe it is because various business lobby groups have quite a lot of influence over the labour party, or maybe the labour party is acutely sensitive to accusations of xenophobia (which the supporters of immigration will trot out whenever there is any discussion of reduction in migration).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Clearly profitability outweighs economic productivity in the service sector.

LikeLike

A pilot programme that prioritised overstayers for deportisation has been suspended by Immigration Minister Iain Lees-Galloway, despite an assurance from Immigration NZ that ethnicity was not a factor that it had ever taken into account.

https://www.stuff.co.nz/business/industries/102931217/immigration-nz-ethnic-profiling-didnt-happen

According to the most recent ABS data, for every 100 000 Australia-born residents there are 202.4 prisoners. The total rate for the entire resident population, however, stands at 170 prisoners per 100 000 residents. This means that foreign-born residents actually have a lower chance of being imprisoned for serious offences than the native-born population (ABS 2010).

A few caveats remain, though. First, the prisoner statistics relate only to the most serious crimes. Second, there is a wide gap between different migrant groups, ranging from an extremely low rate of 28.2 for Indian-born to 555.3 for Samoan-born residents. Third, the figures are not controlled for age or socioeconomic status. Fourth, it may be that foreign-born offenders without Australian citizenship are

deported early on in their criminal careers.

Oliver Hartwich

Chapter 11 Australian Productivity Commission – Population

LikeLike