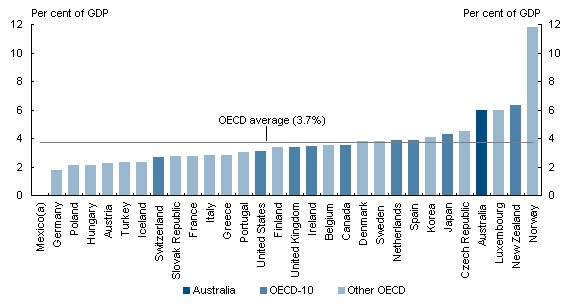

Almost 10 years ago I stumbled on this chart in the background papers to Australia’s tax system review.

Chart 5.11: Corporate tax revenue as a proportion of GDP — OECD 2005

I was intrigued, and somewhat troubled by it. New Zealand collected company tax revenue that, as a share of GDP was the second highest of all OECD countries. And yet New Zealand:

- didn’t have an unusually large total amount of tax as a share of GDP, and

- had had quite low rates of business investment – as a per cent of GDP – for decades, and

- as compared to Australia, just a couple of places to the left, New Zealand’s overall production structure was much less capital intensive (mines took a lot of investment).

And, of course, our overall productivity performance lagged well behind.

Partly prompted by the chart, and partly by a move to Treasury at about the same time, I got more interested in the taxation of capital income. After all, when you tax something heavily you tend to get less of it, and most everyone thought that higher rates of business investment would be a part of any successful lift in our economic performance. That interest culminated in an enthusiasm for seriously considering a Nordic tax system, in which capital income is deliberately taxed at a lower rate than labour income. It goes against the prevailing New Zealand orthodoxy – broad-base, low rate (BBLR) – but even the 2025 Taskforce got interested in the option.

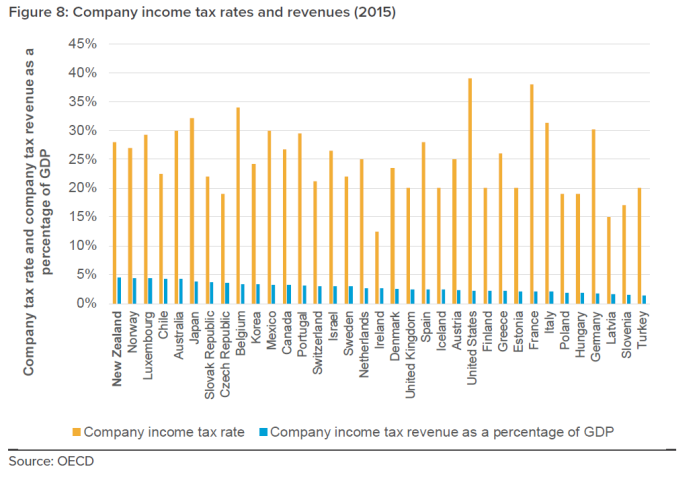

Flicking through the background document for our own new Tax Working Group the other day I came across this chart (which I haven’t seen get any media attention).

It is a bit harder to read, but just focus for now on the blue bars. On this OECD data New Zealand now has company tax revenues that are the highest percentage of GDP of any OECD country. A footnote suggests that if one nets out the tax the government pays to itself (on businesses it owns), New Zealand drops to only fourth highest but (a) the top 5 blue bars are pretty similar anyway, and (b) it isn’t clear who they have dropped out (if it is just NZSF tax that is one thing, but most government-owned businesses would still exist, and pay tax, if in private ownership).

So for all the talk about base erosion and profit-shifting, and talk of possible new taxes on the sales (not profits) of internet companies, we continue to collect a remarkably large amount of company tax (per cent of GDP). Indeed, given that our total tax to GDP ratio is in the middle of the OECD pack, we also have one of the very largest shares of total tax revenue accounted for by company taxes.

The Tax Working Group appears to think this is a good thing, observing that it

“suggests that New Zealand’s broad-base low-rate system lives up to its names”

There is some discussion of the trend in other countries towards lowering company tax rates, but nothing I could see on the economics of taxing business/capital income. It is as if the goose is simply there to be plucked.

There are, of course, some caveats. Our (now uncommon) dividend imputation system means that for domestic firms owned by New Zealanders, profits are taxed only once. By contrast, in most countries dividends are taxed again, additional to the tax paid at the company level. But, of course, in most of those countries, dividend payout ratios are much lower than those in New Zealand, and tax deferred is (in present value terms) tax materially reduced.

And, perhaps more importantly, the imputation system doesn’t apply to foreign investment here at all. Foreign investment would probably be a significant element in any step-change in our overall economic performance. And our company tax rates really matters when firms are thinking about whether or not to invest here at all. And our company tax rates are high, our company tax take is high – and our rates of business investment are low. Tax isn’t likely to be the only factor, or probably even the most important – see my other discussions about real interest and exchange rates – but it might be worth the TWG thinking harder as to whether there is not some connection.

Otherwise, as in so many other areas, we seem set to carry on with the same old approaches and policies and yet vaguely hope that the results will eventually be different.

Well it seems like the old soak the rich argument… I remember Cullen while MoF stating that he thought the tax rate for businesses was irrelevant, when in fact it is extremely important when considering new capital investment…

Maybe one idea worth looking at is a differential rate for smaller businesses – there is something like this operating now in Australia and in a few other countries I think… not saying its a good idea – just something to have a look at and see whether it passes the sniff test…

Iwi enterprises have a tax rate of 17.5%, however, small businesses may also benefit from lower tax rates as well… Worth a punt?

LikeLike

Capital income should be taxed at the same rate as other personal income (minus inflation) and corporate income should not be taxed. And, no, a piece of appreciating land or a painting or whatever doesn’t generate income, not until it is sold.

LikeLike

Capital Income has no cashflow until actually sold and settled. Rather difficult to expect a retired couple in their golden age of doddering around to find the spare cash to pay for the capital increase whilst it is unrealised. What if the person is buying the next house in the next street? Does it mean once he has sold he can’t buy back a similar property in the same street? Does seem to be a major anomaly even to tax on the sale. Therefore it is back to the days to death duties which can be avoided by having Family Trusts as owners.

LikeLike

Yes, once sold a house of the same value cannot replace it if housing in general has appreciated due to the loss of some of the appreciation profit to tax. This isn’t a silver bullet to solve the housing crisis, there are none. Instead about a dozen different things need to be done to fix the housing market, this is only one of them.

LikeLike

We have to be careful how these numbers are analysed. Singapore has a corporate tax rate of 17% but they have a compulsory Company Super contribution rate of 15%. By separating out the corporate tax rate from the retirement of employees there is a perception that countries like Singapore has a lower corporate tax rate. Our Universal Pension payments for retirees come from the the 28% Corporate tax collected that may skew the comparisons quite dramatically.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Michael

I start the tax section of my public finance course with graphs similar to these, and note that NZ’s tax system is so different to most other countries that we have to begin by studying other tax systems in order to understand the full range of possible taxes.

As you hint, one of the main differences is that NZ does not have significant social security taxes (the small ACC levy is the exception), which in other countries are applied to labour income not capital income. This means most other countries tax capital income at lower rates than labour income and thus have a system much closer to the Nordic Dual Income tax system than we do. New Zealand policy makers and politicians invented and swallowed the “broad base low rate” slogan years ago, and have been loathe to recognize the growing international plaudits for dual tax systems. One consequence is that we have high effective taxes on capital income (other than income from land) and low effective tax rates on labour income. This is the opposite combination that European and Nordic countries have adopted. As Peter Lienert (the public finance historian) observed fifteen years ago, if you are going to have a very high tax-GDP ratio like many Nordic countries, you have to make sure you have the most efficient taxes or else you risk crippling your economy. In practice this means taxing labour income more highly than capital income, as labour is supplied more inelastically than capital. Nordic countries even use much of their tax income to induce high labour supply, particularly among women,by subsidising child-care.

Here’s what Joel Slemrod and Jon Bakija say in the fifth edition of their book “Taxing Ourselves” (p407-408).

” If the VAT is the world’s tax success story of the past half century, then a contender for the success story of the next fifty years is a Scandinavian innovation known as the Dual tax System….The basic structure of the DIT is straightforward: combine a graduate tax rate schedule on labour income with a low flat tax on all capital income.

The argument for the DIT, which is especially relevant for small open economies like Scandinavian countries, is that a low capital income tax rate would lessen the incentive both for domestic wealth owners to invest capital outside the country and to invest in hard-to-measure types of capital that aren’t included in the tax base. ….It may come as shock that the Nordic countries, with a reputation for highly progressive tax and other policies, would abandon a graduated tax schedule for capital income. Apparently they believe that a highly progressive tax rate on at least some forms of capital income is an inefficient means of redistributing income compared to a progressive labor income tax, and that inequalities stemming from large inherited stocks of wealth may be better addressed through instruments such as an inheritance tax.”

To me, one of the most disappointing aspects of tax policy over the last decade or so is the limited willingness to discuss different tax options.It is true that the Hall-Rabushka “Flat tax” expenditure tax has not been adopted anywhere yet, or for that matter Bradford’s X-tax, but these ideas have solid academic backing and you would think we could at least consider them. Somehow New Zealanders have bought into the idea that broad-based low-rate income taxes (applied to all forms of income except owner-occupied property) are the best tax system, even though there is not much evidence to support this position. It possibly stems from an unwillingness to reopen the bitterly fought policy battles of the 1980s and 1990s. Yet even if 80 percent of the decisions were right back then, times have changed and it is surely time to consider fixing up the remaining mistakes.

Andrew

LikeLiked by 2 people

You say “One consequence is that we have high effective taxes on capital income (other than income from land) and low effective tax rates on labour income” ????

Please define “capital income”

LikeLike

One thing I did notice that Auckland Council Valuers at the last rates valuation exercise have been doing is there appears to be a larger emphasis on shifting more value towards land value where houses have not had extensive renovations. I noticed this changed emphasis just yesterday filing my lastest tax returns that the land value component of the valuation has shifted upwards dramatically and the Value of Improvements dropped considerably. Perhaps preparing for a more broad based land tax on top of our regular rates and perhaps sneaking it in on top of rates with the Council acting as the tax collector on behalf of the government.

Rather sneaky I thought. I would not have noticed but for the reason that I have adopted current value reporting on my tax returns rather than historical reporting which is more common for most accountants.

LikeLike

Australia does have a 10% GST flat tax rate modelled on the NZ GST introduced in 1986. There was a lot of work for accountants in NZ to consult in Australia when they transitioned their GST system in Australia in 2000. But their system had a large number of exemptions for political reason which makes their system a lot more complex to administer including exemptions for tourists buying in Australia can claim GST refunds from the tax office in the airport. NZ does not give tax refunds to tourists unless they shop in specialty giftshops and at the airport.

Singapore has a GST tax of 7% an increase from 3% in 1993. I was involved in some consulting work over in Singapore when it was introduced in 1993.

Malaysia recently adopted GST and did so as they noted in their study that there are 160 countries that have either adopted VAT or GST broad based tax on consumers and that Malaysia’s tax system needed to come up to speed with the rest of the world.

LikeLike

Thanks for those thoughtful comments Andrew. I largely agree, and made a similar point to that in your last sentence in a post earlier in the week.

I remain attracted to a progressive consumption tax and, like you, lament the limited willingness to look seriously at such options.

LikeLike

Higher depreciation rates on new plant and equipment is really a no brainer. Stimulates the purchase and use of new upto date equipment. allows a better cash flow. Helps the productivity problem.

everyone assumes that business owners are all about profit (which is important.) but many are all about the buiness of doing what they are passionate about. all without exception I suggest love the latest and more efficient equipment to work with but lack of cash restrains that. The alternative is to borrow at extortionate interest rates from the likes of UDC etc. That often doesn’t fit as they want their money back fast whereas the business may have a longer timeline. More cash back before tax will change the picture.

This should not apply to registered motor vehicles.

LikeLike

Michael

Important policy issue. I agree with Andrew that policy is not really research – based. Big problem. Hi tax rate lowers productivity for sure.

LikeLike

Unfortunately Andrew Coleman is wrong about no one else adopting a broad based GST tax system. There are 160 countries that have adopted either VAT or GST with Malaysia recently adopting a 6% GST after considerable studies and then selling it to the Malaysian public as the best thing since sliced bread.

LikeLike

Weshah, I beg to differ on your opinion that tax policy is not really research based. It is one of the most reseached topics in the world with Governments trying to gain revenue from the voters and yet at the same time trying to appease voters so that they do not get tossed out of the Government. Tax working groups are working all the time to get right balance and mix. So you have some of the most brilliant minds dedicated to tax planning accountants, tax lawyers, journalists, tax academics around the world trying to maximise or minimise or simply avoid tax.

LikeLike

Company tax requires making a profit. NZ is full of small companies and very few can move overseas so our carpet installers and car repair yards are interested in making profits. If profits are big enough who seriously cares about tax? Of course even the mega-wealthy hate giving money to the government; we are all convinced they will not give that money the same tender love that we do ourselves. However given a business making a million dollar profit I would rather concentrate on making two million next year than worry about whether the company tax rate is going up or down. Surely it is a very small fraction of NZ companies that have overseas competitors and the big ones like Fonterra that do have competition in export markets are not likely to make investment decisions based primarily on international company tax rates – that might apply to Amazon, IBM, Apple, airlines and mining companies but not NZ businesses.

Conclusion: reduce company tax rate but don’t expect it to have much effect.

LikeLike

To GetGreatStuff

As a point of clarification, I never claimed that no other countries have adopted a broad based GST. To claim that would be absurd, as you point out. The claim is that no-one has implemented a Hall-Rabushka Flat tax or a Bradford-style X tax. These are different.

With a broad based GST, firms pay tax on the difference between their revenue minus their costs excluding wages. (Most countries implement this using the credit-invoice method.) With the Hall-Rabushka plan, firms deduct costs including wages, but wage earners have to pay tax on their wages. Why would you bother to allow wages to be tax deductible for employees but then require employees to pay tax on these wages, rather than simply make them no deductible to firms (the current GST system)? The answer is that you can apply graduated taxes to the employees based on employee income, which means you can make the expenditure tax progressive. Hall Rabushka proposed making the first X-thousand dollars tax free and all subsequent income taxed at a flat rate. Bradford showed you could make it even more progressive.

I wish I were clever enough to have dreamed up such a system. It does mean you can have progressive expenditure taxes if you want them.

LikeLike

Andrew, not too sure what your point actually is. I think you are mixing up Corporate Income tax and Consumer GST which are two very different types of taxes. I don’t think the general public has an issue with the current tax system. Of course there is an element of Labour and Green Party Envy taxes in terms of CGT or a wealth tax that is at odds with the concept of Income tax or broad based consumption taxes.

LikeLike

Interesting discussion Michael. A submission on progressive consumption tax – and anything else that interests you – would be great!

LikeLike