Two local articles on possible tax system/housing connections caught my eye this morning. One I had quite a lot of sympathy with (and I’ll come back to it), but the other not so much.

On Newsroom, Bernard Hickey has a piece lamenting what he describes in his headline as “Our economically cancerous addiction”. The phrase isn’t used in the body of the article, but there is this reference: “our national obsession with property investment”. Bernard argues that the tax treatment of housing “explains much of our [economic]underperformance as a country over the past quarter century”, linking the tax treatment of housing to such indicators (favourites of mine) as low rates of business investment and lagging productivity growth.

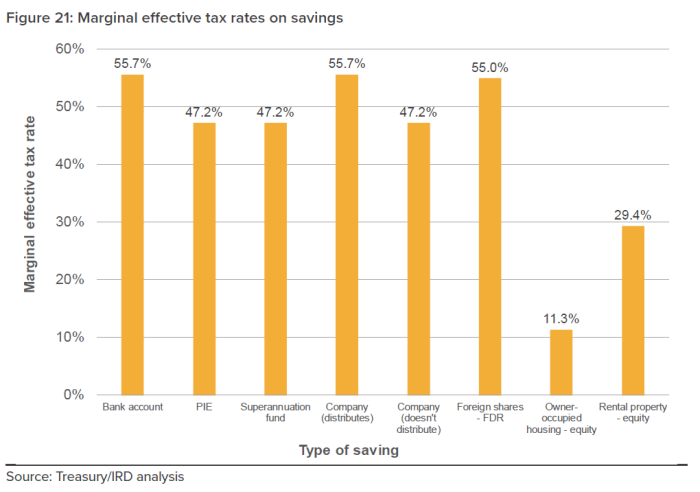

Centrepiece of his argument is this chart from the Tax Working Group’s (TWG) discussion document released last week.

Note that, although the label does not say so, this is an attempt to represent the tax rate on real (inflation-adjusted) returns.

It is a variant of one of Treasury’s favourite charts, that they’ve been reproducing in various places for at least a decade. The TWG themselves don’t seem to make a great deal of it – partly because, as they note, their terms of reference preclude them from looking at the tax-treatment of owner-occupied housing. They correctly note – although don’t use the words – the gross injustice of taxing the full value of interest income when a large chunk of interest earnings these days is just compensation for inflation, not a gain in purchasing power at all. And, importantly, the owner-occupied numbers relate only to the equity in houses, but most people get into the housing market by taking on a very large amount of debt. Since interest on debt to purchase an owner-occupied house isn’t tax-deductible – matching the fact that the implicit rental income from living in the house isn’t taxed – any ‘distortion’ at point of entering the market is much less than implied here.

Bear in mind too that very few countries tax owner-occupied housing as many economists would prefer. In some (notably the US) there is even provision to deduct interest on the mortgage for your owner-occupied house. You – or Bernard, or the TOP Party – might dislike that treatment, but it is pretty widespread (and thus likely to reflect some embedded wisdom). And, as a reminder, owner-occupation rates have been dropping quite substantially over the last few decades – quite likely a bit further when the latest census results come out. Perhaps a different tax system would lead more old people – with lots of equity in a larger house – to downsize and relocate, but it isn’t really clear why that would be a socially desirable outcome, when maintaining ties to, and involvement in, a local community is often something people value, and which is good for their physical and mental health.

So, let’s set the owner-occupied bit of the chart aside. It is simply implausible that the tax treatment of owner-occupied houses – being broadly similar to that elsewhere – explains anything much about our economic underperformance. And, as Bernard notes, it isn’t even as if, in any identifiable sense, we’ve devoted too many real resources to housebuilding (given the population growth).

So what about the tax treatment of rental properties? Across the whole country, and across time, any distortion arises largely from the failure to inflation-index the tax system. Even in a well-functioning land market, the median property is likely to maintain its real value over time (ie rising at around CPI inflation). In principle, that gain shouldn’t be taxed – but it is certainly unjust, and inefficient, to tax the equivalent component of the interest return on a term deposit. Interest is deductible on rental property mortgages, but (because of inflation) too much is deductible – ideally only the real interest rate component should be. On the other hand, in one of the previous government’s ad hoc policy changes, depreciation is not deductible any longer, even though buildings (though not the land) do depreciate.

But, here’s the thing. In a tolerably well-functioning market, tax changes that benefit one sort of asset over others get capitalised into the price of assets pretty quickly. We saw that last year, for example, in the US stock market as corporate tax cuts loomed.

And the broad outline of the current tax treatment of rental properties isn’t exactly new. We’ve never had a full capital gains tax. We’ve never inflation-adjusted the amount of interest expense that can be deducted. And if anything the policy changes in the last couple of decades have probaby reduced the extent to which rental properties might have been tax-favoured:

- we’ve markedly reduced New Zealand’s average inflation rate,

- we tightened depreciation rules and then eliminated depreciation deductions altogether,

- the PIE regime – introduced a decade or so ago – had the effect of favouring institutional investments over individual investor held assets (as many rental properties are),

- the two year “brightline test” was introduced, a version of a capital gains tax (with no ability to offset losses),

- and that test is now being extend to five years.

If anything, tax policy changes have reduced the relative attractiveness of investment properties (and one could add the new discriminatory LVR controls as well, for debt-financed holders). All else equal, the price potential investors will have been willing to pay will have been reduced, relative to other bidders.

And yet, according to Bernard Hickey

It largely explains why we are such poor savers and have run current account deficits that built up our net foreign debt to over 55 percent of GDP. That constant drive to suck in funds from overseas to pump them into property values has helped make our currency structurally higher than it needed to be.

I don’t buy it (even if there are bits of the argument that might sound a bit similar to reasoning I use).

A capital gains tax is the thing aspired to in many circles, including the Labour Party. Bernard appears to support that push, noting in his article that we have (economically) fallen behind

other countries such as Australia, Britain and the United States (which all have capital gains taxes).

There might be a “fairness” argument for a capital gains tax, but there isn’t much of an efficiency one (changes in real asset prices will mostly reflect “news” – stuff that isn’t readily (if at all) forecastable). And there isn’t any obvious sign that the housing markets of Australia and Britain – or the coasts of the US – are working any better than New Zealand’s, despite the presence of a capital gains tax in each of those countries. If the housing market outcomes are very similar, despite differences in tax policies, and yet the housing channel is how this huge adverse effect on productivity etc is supposed to have arisen, it is almost logically impossible for our tax treatment of houses to explain to any material extent the differences in longer-term economic performance.

And, as a reminder, borrowing to buy a house – even at ridiculous levels of prices – does not add to the net indebtedness of the country (the NIIP figures). Each buyer (and borrower) is matched by a seller. The buyer might take on a new large mortgage, but the seller has to do something with the proceeds. They might pay down a mortgage, or they might have the proceeds put in a term deposit. House price inflation – and the things that give rise to it – only result in a larger negative NIIP position if there is an associated increase in domestic spending. The classic argument – which the Reserve Bank used to make much of – was about “wealth effects”: people feel wealthier as a result of higher house prices and spend more.

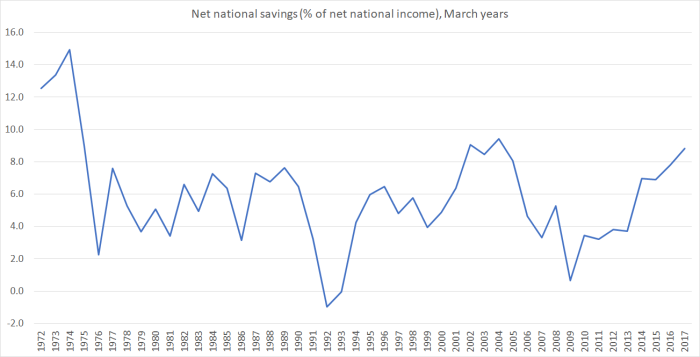

But here is a chart I’ve shown previously

National savings rates have been flat (and quite low by international standards) for decades. They’ve shown no consistent sign of decreasing as house/land prices rose and – for what its worth – have been a bit higher in the last few years, as house prices were moving towards record levels.

What I found really surprising about the Hickey article was the absence of any mention of land use regulation. If policymakers didn’t make land artificially scarce, it would be considerably cheaper (even if there are still some tax effects at the margin). And while there was a great deal of focus on tax policy, there was also nothing about immigration policy, which collides directly with the artificially scarce supply of land.

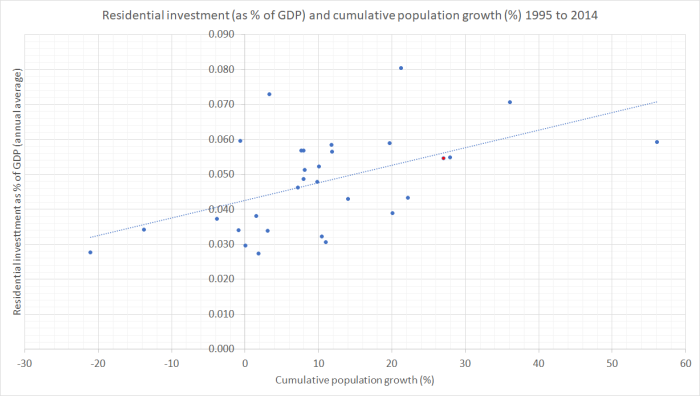

I’ve also shown this chart before

These are averages for each OECD country (one country per dot). New Zealand is the red-dot – very close to the line. In other words, over that 20 year period we built (or renovated/extended) about as much housing as a typical OECD country given our population growth. But, as I noted in the earlier post on this chart

The slope has the direction you’d expect – faster population growth has meant a larger share of current GDP devoted to housebuilding – and New Zealand’s experience, given our population growth, is about average. But note how relatively flat the slope is. On average, a country with zero population growth devoted about 4.2 per cent of GDP to housebuilding over this period, and one averaging 1.5 per cent population growth per annum would have devoted about 6 per cent GDP to housebuilding. But building a typical house costs a lot more than a year’s average GDP (for the 2.7 people in an average dwelling). In well-functioning house and urban land markets you’d expect a more steeply upward-sloping line – and less upward pressure on house/land prices.

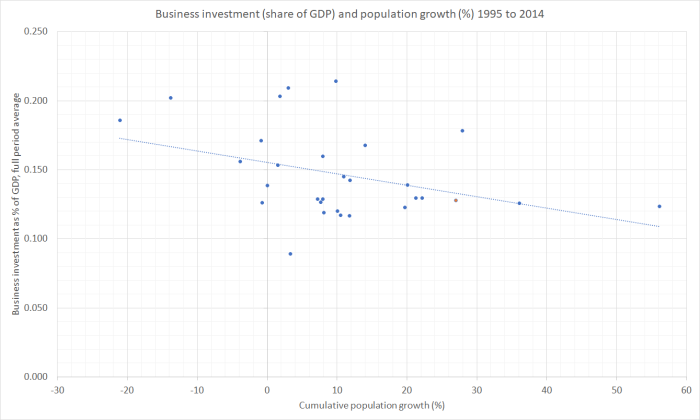

And, since Hickey is – rightly – focused on weak average rates of business investment here is another chart from the same earlier post.

Again, New Zealand is the red dot, close to the line. Over the last 20 years, rapid population growth – such as New Zealand has had – has been associated with lower business investment as a share of GDP. You’d hope, at bare minimum, for the opposite relationship, just to keep business capital per worker up with the increase in the number of workers.

This issue, on my telling, isn’t the price of houses – dreadful as that is – but the pressure the rapid policy-fuelled growth of the population has put on available real resources (not including bank credit). Resources used building or renovating houses can’t be used for other stuff.

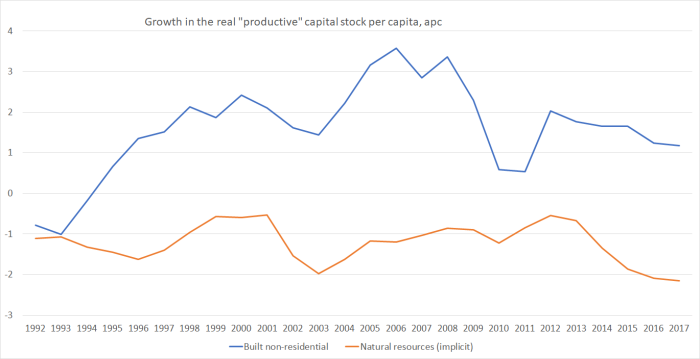

And one last chart on this theme.

The blue line shows the annual per capita growth rate in the real capital stock, excluding residential dwellings (it is annual data, so the last observation is for the year to March 2017), but as my post the other day illustrated even in the most recent national accounts data, business investment has been quite weak. I’ve added the orange line to account for land and other natural resources that aren’t included in the official SNZ capital stock numbers. We aren’t getting any more natural resources – land, sea, oil and gas or whatever – (although of course sometimes things are discovered that we didn’t know had been there). The orange line is just a proxy for real natural resources per capita – as the population grows there is less per capita every year, even if everything is renewable, as many of New Zealand’s natural resources are (and thus the line is simply the inverted population growth rate).

In New Zealand’s case at least, rapid population growth (largely policy driven over time) seems to have been – and still to be – undermining business investment and growth in (per capita) productive capacity. Land use regulation largely explains house and urban land price trends. And it seems unlikely that any differential features of New Zealand’s tax system explain much about either outcome.

The other new article that caught my eye this morning was one by Otago University (and Productivity Commission) economist, Andrew Coleman. He highlights, as he has in previous working papers, how unusual New Zealand’s tax treatment of retirement savings is, by OECD country standards. Contributions to pension funds are paid from after-tax income, earnings of the funds are taxed, and then withdrawals are tax-free. In many other countries, such assets are more often accumulated from pre-tax income, fund earnings are largely exempt from tax, and tax is levied at the point of withdrawal. The difference is huge, and bears very heavily on holding savings in a pension fund.

As Coleman notes, our system was once much more mainstream, until the reforms in the late 80s (the change at the time was motivated partly by a flawed broad-base low rate argument, and partly – as some involved will now acknowledge – by the attractions of an upfront revenue grab.

The case for our current practice is weak. There is a good economics argument for taxing primarily at the point of spending, and not for – in effect – double-taxing saved income (at point of earning, and again the interest earned by deferring spending). And I would favour a change to our tax treatment of savings (I’m less convinced of the case for singling out pension fund vehicles). I hope the TWG will pick up the issue.

That said, I’m not really persuaded that the change in the tax treatment of savings 30 years ago is a significant part of the overall house price story. The effect works in the right direction – and thus sensible first-best tax policy changes might have not-undesirable effects on house prices. But the bulk of the growth in real house (and land) prices – here and in other similar countries – still looks to be due to increasingly binding land use restrictions (exacerbated in many places by rapid population growth) rather than by the idiosyncracies of the tax system.

With respect to this point:

“In some (notably the US) there is even provision to deduct interest on the mortgage for your owner-occupied house. You – or Bernard, or the TOP Party – might dislike that treatment, but it is pretty widespread (and thus likely to reflect some embedded wisdom).”

Yes, interest deductions on mortgages do apply, but conversely, a seller of their own home does pay capital gains tax unless they re-purchase at a similar or higher price, as I understand it.

LikeLike

Yes, there is some CGT on owner-occupied houses, but considerable “rollover relief” which means that few ordinary homeowners are caught. Those provisions were made less taxing about 20 years ago and may (at the margin) have contributed to the early stages of the US house price boom).

LikeLike

Available to rent Rental stock is down 70% in Wellington and down 35% in Auckland. Rents have moved up considerably as a result. These are clear signs of under investment in rental property rather than an over investment. Bernard Hickey does not know what he is taking about.

The misallocation in resources is the continued focus on Primary Industries as our top industries. Billions of dollars of taxpayer subsidies have gone into roads for Fonterra to move trucks around to pick up milk from farmers and for irrigation so that hectares and hectares of farmland is productive.

Billions have to be spent on tree planting under the Paris Agreement to off set the pollution from waste production of 10 million cows and 30 million sheep and the carbon dioxide from the agricultural industry. otherwise the taxpayer would have to subsidise the Paris Agreement. This is why we do not spend on productive industries. We are subsidising the Primary Production industries. Nothing to do with property owners or rental property owners.

LikeLike

Economic under performance is due to our other largest industry which is Tourism. Tourists need to be serviced and they need housing. You need more and more workers to clean, groom and service tourists. They in turn need to eat and be housed. More and more tourists now a $11 billion industry reduces economic productivity as the best service equate to more people and not less.

LikeLike

“More and more tourists now a $11 billion industry reduces economic productivity as the best service equate to more people and not less.” You missed the critical piece, its more low paid work.

Economic under performance has no one cause, and to fix it one needs to know the main three causes.

Road user tax income still exceeds roading expenditure (i think), certainly does motorway work that is population driven, so there is no way any body gets taxpayer subsidies except the main centres.

LikeLike

Where on earth is the horticultural industry subsidised ?

Are rentals not subsidised by Government.?

LikeLike

The government has 2 choices build their own social houses or supplement market rents. No one will rent out their properties to tenants that are prone to damaging property and do not pay rent. The government needs to provide social housing either by paying out accomodation supplements or build houses. The government with $10 billion of land can’t build houses. They can’t get rid of those social tenants living in 2 million dollar stand alone houses to build high rise high density houses on that land whilst those long term social tenants are still alive. Can’t be seen getting rid of old people from those $2 million social houses.

Accomodation supplements are not subsidies. They are supplements to meet market rents.

It’s similar to the big argument that Shane Jones is having with Air NZ. The regional routes are being shut down because the cost of keeping those routes open is too expensive. Shane jones has travelled the regional routes and he wants continuity in his travel plans. The government has 2 choices either supplement the cost of that travel and pay Air NZ or face the consequence of not having flights. Yes it can force Air NZ to run at a loss but then the private owners will take fright and sell their shares and get out of private ownership. Similarly, it can force private landlords to take below market rents but then you get into a situation that no one rents to social tenants and they are out on the streets.

LikeLike

The horticulture industry I would guess fall under agriculture. Plants need nitrates and they need water and they need transport. Nitrates contaminate water supplies and cause algae bloom. Generally the subsidies are in irrigated water and roads into rural farmland. 50% of carbon dioxide emissions are from the agricultural industries which under Paris Agreement needs to be paid for. Therefore either plant more trees which is the billion tree that Shane Jones is trying to plant from his regional fund to try and offset the carbon dioxide created by the Agriculture industries that is killing the planet Earth.

LikeLike

I’m not sure if something being widespread is necessarily an indicator of its wisdom. We do lots of stupid things across loads of societies.

LikeLike

agree not necessarily, but there is plenty of wisdom/reason embedded in societal practices that initially look odd to, say, economists.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on The Inquiring Mind and commented:

Well worth reading with care

LikeLike

“And, as a reminder, borrowing to buy a house – even at ridiculous levels of prices – does not add to the net indebtedness of the country (the NIIP figures). Each buyer (and borrower) is matched by a seller. The buyer might take on a new large mortgage, but the seller has to do something with the proceeds.”

??? this sounds like a Ponzi scheme. One could say the same for bitcoin. Ok as long as everyone keeps buying.

Over the long run assuming that land values eventually revert to the mean (interest rates back up, immigration finally drops off & the planning system is unwound to some degree) then much of the excessive increase in land value will be removed. The last buyer(s) will be saddled with debt and lower capital (house + land) values to offset it. The net indebtedness of the country will be affected.

LikeLike

Even in that bleak/optimistic world – I’m not sure which, but it would be great if the land laws were freed up – it still doesn’t change the net external indebtedness of the country much. In fact, in the NZ case it might slightly improve that specific measure – domestic borrowers default on loans, and those losses are borne initially by bank shareholders (mostly, in our case, Australian). If the banks failed either there would be a govt bailout – still no change in NIIP – or creditors/depositors would bear the losses, and quite a lot of the wholesale creditors are foreign.

I’m not suggesting housing booms or busts are necessarily benign things just that – of themselves – they don’t change the NIIP position. of course, house prices booms often occur in the context of economic booms and surges in investment (often poor quality – see Ireland), which results in a widening in the current account deficit and a worsening in the NIIP position. That effect tends to be reversed in the subsequent painful bust.

I remain pessimistic on prospects for reform, so don’t expect any big sustained house price correction. THere will be another recession along, but no country that has messed up its land use laws as we have has yet succeeded in undoing them. I long for us to be first, but am not optimistic.

LikeLike

I have a friend that has only bought 2 houses in his 60 years. The first is a Remuera property that he paid $50k for in his teens which he sold recently and at the same current period he paid $3 million for his St Heliers property with a sale price of $3 million for his remuera property. He told me that he is reaching an age that he wanted to retire and the property market currently was slow. So I offered him $2 million for his property. He said to me “NO”. Hell would freeze over first before he would sell for less than his purchase price of $3 million. But I said he will still make a capital profit of $1.95 million because all of that was purely equity growth. But no matter how hard I tried he still saw it as a capital loss of $1 million from his $3 million buy price.

LikeLike

All housing debt has a limited lifespan. The bank only offers 30 year debt. Interest only debt is only 5 years and the principle has to be paid. Commercial debt usually has only a 10 year lifespan and then has to be paid. Debt has to be paid off eventually. The bank demands it. It is a question of when not if.

LikeLike

Michael you might feel that the politics of housing reform is too difficult -maybe it is -maybe it isn’t. A few months in government is too short a time to make a call on this. But let’s be clear -the head in the sand, do nothing approach has economic consequences beyond increasingly dividing NZ into winning home owning and losing renting groups.

It affects productivity and resource allocation and it is this I would like to hear more from Grant Robertson.

In particular, on how the pressures from land-use restrictions/unaffordable housing has created barriers of entry to the labour market, affected productivity and misallocated resources. Yale Law Professor David Schleicher explains the general case argument here.

View at Medium.com

In the specific NZ case, a lot of the labour shortages and wage increase demands from teachers and nurses etc is a result of high house prices/rents, which have risen faster than wage growth.

It would be good to get some indication from Grant on where he stands on the continuum of treating the underlying cause -housing pressures with implications for government expenditure wrt expensive infrastructure requests to unlock land-use to create a more elastic housing supply potential versus treating the symptoms -stressed out teachers/nurses working with labour market shortages demanding expensive wage increases?

There is a difficult choice, especially given NZ’s government fiscal constraints -treat the symptoms or treat the cause?

It would be also good if NZ’s business journalists like Bernard Hickey got down to this real-life nitty gritty stuff…..

LikeLike

Tiny apartments haven’t solved Hong Kong’s affordability problems (if I follow your argument)

https://www.cnbc.com/2017/04/09/heres-why-hong-kong-housing-is-so-expensive.html

LikeLike

Sorethumb -most serious affordable housing advocates are asking to remove restrictions on cities building up and out (technically we want to make both the intensive and extensive margins be more elastically supplied in response to demand).

Only removing a few minor restrictions for intensification will almost certainly be unsuccessful. The effect will be mostly capitalised into increased land prices rather than more built residential spaces, because it doesn’t fundamentally change the problem of monopolisation to a few the ability to supply additional residential space.

Removing planning restrictions and opening up infrastructure enabled land-use areas needs to done in a large scale manner to create competitive market disciplines.

The government either has to commit to innovative new infrastructure funding mechanisms where growing urban areas can capture some of that growth to fund its own infrastructure needs or the government uses its own balance sheet to supply more infrastructure directly.

If the government ignores these choices or addresses them in a half- hearted manner and instead focuses most of its attention on treating the symptoms by mechanisms, such as, public sector wage increases and private sector wage subsidies -like Working for Families then the underlying problem is not fixed and the can is kicked down the road again……

LikeLike

This debate might all seem very dry and academic. But real issues and hard choices need to be made.

I work as registered nurse in Hillmorton hospital in Christchurch. The places is close to full meltdown -almost every shift there is one or more staff member doing a double 16 hour shift. Occupancy is regularly over 100% and acuity is high. Google Hillmorton hospital and you will see incident after incident (fires,assaults, injuries…) -a small tip of the iceberg. Something needs to be done and it will not be cheap…

But I also know the staffing situation would be better if housing costs for younger staff starting out in life was cheaper. I know of staff who working in Christchurch could not save a penny due to the high cost of renting, but in Australia (admittedly in the case I am most familiar with, a smaller city of about 100,000) their rent is lower and salary higher and they have saved $1000’s in quick order.

My situation, Hillmorton hospital’s situation and Christchurch’s housing situation is repeated up and down the country.

Grant, Jacinda and co. have some tough choices -I hope they choose wisely.

LikeLike

In Auckland, the intensity solution can really only be realised by removing the Viewshaft height limits imposed by the Unitary Plan. The Viewshafts cover 40 million sq metres of land around 57 sacred mounts and prevent highrise. Logically you would expect suburbs like Mt Eden, Mt Albert, Mt Roskill next to the CBD to be the next suburbs to be zoned unlimited highrise. But due to the Viewshafts most of these CBD adjoining suburbs will remain single dwelling and heights won’t exceed 3/4 level accommodation. This is not going to change because Council is pretty much run by the Labour Party with Phil Goff former Leader of the Labour Party is the mayor. The Unitary Plan has been reviewed by a panel of Independent experts presided over by a judge already in consultation with Auckland 2040 and Heritage NZ. 5 years of negotiation is not that easily taken apart by a bandaid government with the Greens and NZFirst essentially a Maori Party and Labour having to appease the 7 Maori seats.

Phil Goff has already issued a plan for $30 billion for infrastructure spending in Auckland which he hopes the government will gift to Auckland which is just not available.

The Labour government is still drip feed spending $15 billion over the next 10 years in Christchurch and Kaikoura, twin disasters. There is no money available. No matter how innovative you get it does mean that the government has a looming mega budget deficit. Grant Robertson and Jacinda Ardern has to bend over and make peace at the Election lies they have promised and Kow Tow to Steven Joyce for the $11.7 billion budget hole that he predicted as being conservative and accurate and tell the public the Labour Party lied and 7 economists including Bernard Hickey that backed them do not know mathematics and can’t add.

LikeLike

Hong Kong on land area of 2,750 skm has 7.5 million people. Auckland has 5,000 skm with 1.5 million people. Going up will still equate to cheaper housing in Auckland. But because of the 57 sacred mounts we have created an artificial island of 550skm equivalent to the size of Singapore with 729 skm with 5 million people.

LikeLike

I am not sure about the argument that borrowing to buy a house has no impact on NIIP. It seems to me that it is a dynamic process with many different channels – e.g. expectations. My understanding is that the expansion of Australian banks balance sheets is not able to be funded by domestic deposits and is significantly funded by a continuous flow from offshore wholesale markets.

Call me Presbytarian, but I would prefer if it was a cultural norm for every household to keep 3 months salary in cash as a precautionary against emergencies and this was supported by the tax system by an exemption on interest up to say $20k per person. No doubt the Treasury would be horrified (big revenue loss for initially small behaviour change) but it’s about the kind of values we want to have as a society.

LikeLike

NZ households savings deposits equal to $170 billion at Dec 2017. NZ household housing debt is $175 billion at Dec 2017. Offshore funding is not for NZ households. It funds the $60 billion of farming debt and the $150 billion in commercial debt to run businesses and another $60 billion to buy investment property.

Most of NZ debt is actually for business purposes. Largely due to the lack of depth of NZ capital markets and kiwis prefer full control of their businesses rather than lose control with third party capital.

LikeLike

Hickey is a pure leftist when it come to economics… not trained in the subject at all and prone to bandaid simple solutions to complex problems. Anyone who thinks we can tax our way to prosperity is a fool…

Let’s be clear.. property development is high risk, low return… developers make at least as much as they lose and are widely optimistic about their abilities and skills. Complex and aggressive local zoning rules drive up costs and risk… it’s no wonder housing is expensive in NZ given the institutional settings. Hickey is focus on a visible ‘cause’ but not the root cause. Less land and zoning regulation will help lower costs but is a dream to think that will occur.

I know of two apartment developments that are turning into hotel developments simply because the rules are less restrictive and thus are more profitable… no need for car parks… a huge cost and no stupid balconies either… it’s economics pure and simple… the planners at council are ignorant of the real world… and it costs all of us

LikeLiked by 1 person

Car parking has already been removed under the Unitary Plan for Apartment and Terrace housing zones. It is just as difficult to build hotels as it is to build apartments. The difference is the profit margin is higher in a serviced apartment as part of a hotel. Selling an apartment as part of a commercial activity allows zero rated GST on the sale price which means the seller does not need to pay GST of 15% on the sale price. The buyer is required to be GST registered to purchase and usually will not be aware that the GST obligations have been passed from the seller to the buyer. If the buyer decides to rent out and to live in the property outside of the hotel in the future, There would be a deemed sale in the change of use which triggers GST payable by the buyer.

LikeLike

Also zero rating still allows the GST on the building costs to be refundable. Therefore if you can get a buyer to accept zero rating ie Buyer registers as a GST buyer, you can potentially get extra profit margin from the GST refunded on the build cost and you do not have to pay GST on the sell price.

LikeLike

Two points: Not having to build carparks in the basement significantly lowers the build cost and the risk of construction… hotels don’t need carparks. So there is margin there by having a simpler and lower risk build project

If you don’t collect GST you can’t claim it on the other side… so the profit margin is not really there. In fact it is worse. You buy some land and nowadays there is no GST on land claimable except in very special circumstances, however, when you develop and then sell the finished product GST is payable on the entire sale price… ouch!

LikeLike

Fat Bastard, your comments are wrong. Apartment and terrace housing zones under the Unitary Plan does not need car parks either. If you buy land from a non gst registered entity you can claim the GST. You have to zero rate if you buy from a gst registered entity. But the build cost as a developer, you can claim the GST on the build cost. When you sell through a hotel pool you usually zero rate the sale price as it is a commercial activity you can request buyer to be GST registered.

LikeLike

Note that you are mixing up GST Exempt activity on residential property versus Zero rated GST activity. They operate differently.

LikeLike

GGS: do you sleep or are you multiple individuals working different shifts?

LikeLiked by 1 person

We cant develop our way to prosperity either and the reason is resource constraints to population.

A land tax might hinder development but it recognises some fundamentals of a civil society, for example, some things belong to the members of the nation.

You could look at Queenstown as an example of ‘wealth creation”. Queenstowns GDP and value of it’s capital stock is way above what it was in 2004. The taxi driver from Mumbai might feel at home but others can’t get out fast enough.

Of course property developers embrace globalisation because we function in a social and physical environment. Status* and locale are available to the wealthy.

* status is a predictor of health even when material needs are accounted for.

LikeLike

But it does get 1 million visiting tourist a year and therefore the infrastructure needs to be developed to capture the spending by the 1 million visiting tourists. Tourists need to eat so restaurants need to be developed. Tourists need to go shopping so retail shops, supermarkets need to be developed Tourists need to be cleaned and groomed and serviced by workers. These workers need a place to stay so housing accomodation needs to be developed to house the workers. Others can’t get out fast enough but more others need to work and therefore come flocking in.

LikeLike

How about the worldwide suppression of interest rates following the GFC by central banks. This has engendered a massive increase in credit and consequently asset prices, as well as the case for capital gains taxes. RBNZ is merely a fast follower of northern hemisphere central banks in practicing financial repression to supposedly achieve inflation and employment targets. Chasing these chimera has has engendered a massive build up of world debt, and potential financial instability, as well as causing social instability. Target inflation at zero and the need for capital gains taxes will disappear.

LikeLike

Global inflation is currently low to zero. Capital gains have not disappeared.

LikeLike

I remember reading a history of Diamond Harbour. The Lyttelton County Council would develop land available and get a bit peeved when people didn’t move there. Where my parents lived we had double sections with golden ake-ake hedges and holes either side so we could walk through to the neighbours.

LikeLike

Jesse Mulligan needs a bigger house for a growing family

APRIL 29, 2016

Immigration is high, and they’re all coming to Auckland – that’s not an accident, it’s part of the plan.

https://thespinoff.co.nz/society/29-04-2016/auckland-property-has-become-a-farce-but-who-is-the-asshole-to-blame/

LikeLike

No it is because Auckland is the most visited city in New Zealand. Auckland Airport now handles 19 million inbound and outbound passengers every 12 months. 19 million people need to be serviced by workers, baggage handling, cleaning, feeding, shopping, transporting. Blame Auckland Airport as the gateway.

LikeLike