The Reserve Bank of New Zealand has long been averse to references to a “natural rate of unemployment” or its cognate a “non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment” (NAIRU). It started decades ago, when the unemployment rate was still very high, emerging from the structural reforms and disinflation efforts of the late 80s. We didn’t want to lay ourselves open to charges, eg from Jim Anderton, that we regarded unemployment as natural or inevitable, or were indifferent to it, let alone that we were in some sense targeting a high rate of unemployment. Such a criticism would have had little or no analytical foundation – we and most mainstream economists held that a NAIRU or “natural” rate of unemployment was influenced largely by labour market regulation, welfare provisions, demographics, and other structural aspects (eg rate of turnover in the labour market) that were quite independent of monetary policy. But the risk was about politics not economics, and every election there were parties looking to change the Reserve Bank Act. And so we never referrred to NAIRUs if we could avoid it – which we almost always could – preferring to focus discussions of excess capacity etc on (equally unobservable) concepts such as the output gap. In our formal models of the economy, a NAIRU or a long-run natural rate could be found lurking, but it made little difference to anything (inflation forecasts ran off output gap estimates and forecasts, not unemployment gaps).

Other central banks do things a bit differently, perhaps partly because in some cases (notably Australia and the US) there is explicit reference to employment/unemployment in monetary policy mandates those central banks are working to. In a recent article, the Reserve Bank of Australia observed that

“When updating the economic forecasts each quarter, Bank staff use the latest estimate of the NAIRU as an input into the forecasts for inflation and wage growth”

It may not make their monetary policy decisions consistently any better than those here, but it is a difference in forecasting approach, and in how the RBA is prepared to talk about the contribution of unemployment gaps (as one indicator of excess capacity) to changes in the inflation rate.

I’ve been arguing for some years – first inside the Bank, and more recently outside – that our Reserve Bank put too little emphasis (basically none) on unemployment gaps (between the actual unemployment rates and the best estimate of a NAIRU). It has been the only central bank in the advanced world to start two tightening cycles since 2009, only to have to reverse both, and I had noted that this outcome (the reversals) wasn’t that surprising when for years the unemployment rate had been above any plausible estimate of the NAIRU. The Bank sought to fob off criticisms like this with a new higher-tech indicator of labour market capacity (LUCI) – touted by the Deputy Governor in a speech, used in MPSs etc – only for that indicator to end badly and quietly disappear.

But since the change of government – a government promising to add an explicit employment dimension to the Bank’s monetary policy objective (now only 12 days to go til the new Governor and we still haven’t seen the new PTA version) – there has been some pressure for the Bank to be a bit more explicit about how it sees, and thinks about, excess capacity in the labour market, including through a NAIRU lens. In last month’s Monetary Policy Statement, they told us their point estimate of the NAIRU (4.7 per cent) and in the subsequent press conference, the Governors told us about the confidence bands around those estimates. All this was referenced to an as-yet-unpublished staff research paper (which still seems an odd inversion – senior management touting the results before the research has had any external scrutiny).

Last week, the research paper was published. Like all RB research paper it carries a disclaimer that the views are not necessarily those of the Reserve Bank, but given the sensitivity of the issue, and the reliance on the paper at the MPS press conference, it seems safe to assume that the paper contains nothing that current management is unhappy with. What the new Governor will make of it only time will tell.

There was interesting material on the very first page, where the authors talk about the role of monetary policy.

The focus of monetary policy is to minimise fluctuations in cyclical unemployment, as indicated by the gap between the unemployment rate and the NAIRU, while also maintaining its objective of price stability.

I would very much agree. In fact, that way of stating the goal of monetary policy isn’t far from the sort of wording I suggested be used in the amended Reserve Bank Act. Active discretionary monetary policy exists for economic stabilisation purposes, subject to a price stability constraint. But the words are very different from what one has typically seen from the Reserve Bank over the years (including, for example, in their Briefing to the Incoming Minister late last year).

But the focus of the research paper isn’t on policy, but on estimation. The authors use a couple of different techniques to estimate time-varying NAIRUs. Since the NAIRU isn’t directly observable, it needs to be backed-out of the other observable data (on, eg, inflation, wages, unemployment, inflation expectations) and there are various ways to do that. The authors draw a distinction between a “natural rate of unemployment” and the NAIRU: the former, conceptually is slower moving (in response to changes in structural fundamentals – regulation, demographics etc), while the NAIRU can be more cyclical but tends back over time to the longer-term natural rate. I’m not myself convinced the distinction is that important – and may actually be harmful rhetorically – but here I’m mostly just reporting what the Bank has done.

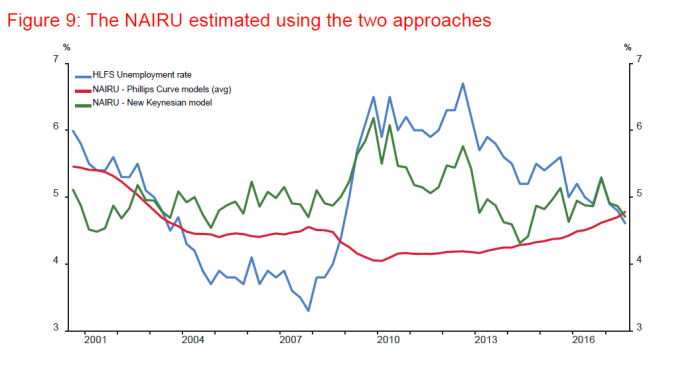

The first set of estimates of the NAIRU are done using a Phillips curve, in which wage or price inflation is a function of inflation expectations, the gap between the NAIRU and the unemployment rate, and some near-term supply shocks (eg oil price shocks). Here is their chart showing the three variants the estimate, and the average of those variants.

Perhaps it might trouble you (as it does me) but the authors never mention that their current estimates of the New Zealand NAIRU, using this (pretty common) approach, are that it has been increasing for the last few years. Frankly, it doesn’t seem very likely that the “true” NAIRU has been increasing – there hadn’t been an increase in labour market regulation, the welfare system hadn’t been becoming more generous, and demographic factors (a rising share of older workers) have been tending to lower the NAIRU.

As it happens, the authors have some other estimates, this time derived from a small structural model of the economy.

Even on this, rather more variable, measure, the current central estimate of the NAIRU is a bit higher than the authors estimate it was in 2014. But the rather bigger concern is probably the extent to which over 2008 to 2015, the estimated NAIRU on this model seems to jump around so much with the actual unemployment rate. Again, the authors offer no thoughts on why this is, or why the pattern looks different than what we observed in the first half of their sample. Is there a suggestion that the model has trouble explaining inflation with the variables it uses, and thus all the work is being done by implicitly assuming that what can’t otherwise be explained must be down to the (unobserved) NAIRU changing? Without more supporting analysis I just don’t find it persuasive that the NAIRU suddenly shot up so much in 2008/09. For what it is worth, however, do note that the actual unemployment rate was well above the NAIRU (beyond those grey confidence bands) for years.

Here is what the picture looks like when both sets of estimates are shown on the same chart.

On one measure, the NAIRU fell during the 08/09 recession, and on the other it rose sharply. On one measure the NAIRU has been steadily rising for several years, while on the other it has been jerkily falling. No doubt the Bank would like you to focus on the end-point, when the two sets of estimates are very close, but the chart does have a bit of a “a stopped clock is right twice a day” look to it. When the historical estimates coincide it seems to be more by chance than anything else, with no sign of any consistent convergence.

I noted the end-point, where the two estimates are roughly the same. But end-points are a significant problem for estimating these sorts of time-varying variables. The authors note that in passing but, somewhat surprisingly, they give us no sense of how material those revisions can be, and have been in the past. I went back to the authors and asked

I presume you’ve done real-time estimates for earlier periods, and then checked how – if at all – the addition of the more recent data alters the estimates of the NAIRU for those earlier periods, but if so do you have any comments on how significant an issue it is?

To which their response was

An assessment of the real-time properties of the NAIRU and the implied unemployment gap was beyond the scope of our paper.

Which seems like quite a glaring omission, if these sorts of model-based estimates of a time-varying NAIRU are expected to play any role in forecasting, or in articulating the policy story (as the Governors did in February).

As it happens, the Reserve Bank of Australia published a piece on estimating NAIRUs etc last year. As a Bulletin article it is a very accessible treatment of the issue. The author used the (reduced form) Phillips curve models (of the sort our Reserve Bank used in the first chart above).

The solid black line is the current estimate of Australia’s NAIRU over the whole of history. But the coloured lines show the “real-time” estimates at various points in the past. In 1997 for example (pink line) they thought the NAIRU was increasing much more – and thus there was less excess labour market capacity – than they now think (or, their model now estimates) was the case. In 2009 there was a stark difference in the other direction. Using this model, the RBA would have materially underestimated how tight the labour market actually was.

It would be surprising if a comparable New Zealand picture looked much different, but it would be nice if the Reserve Bank authors would show us the results. These end-point problems don’t mean that the model estimates are useless, but rather that they are much more useful for identifying historical NAIRUs (valuable for all sorts of research) than for getting a good fix on what is going on right now (the immediate policy problem). That is true of many estimates of output gaps, core inflation (eg the RB sectoral core measure) and so on.

Having said that, at least the Australian estimates suggest that Australia’s NAIRU has been pretty steadily falling for the last 20 years or so, with only small cyclical dislocations. Quite why the Reserve Bank of New Zealand’s Phillips curve models suggest our NAIRU has been rising – when demographics and welfare changes typically point the other way – would be worth some further examination, reflection, and commentary (especially if Governors are going to cite these estimates as more or less official).

Comparing the two articles, I noticed that the RBA had used a measure of core inflation – their favoured measure, the trimmed mean – for their Phillips curve estimates, while the RBNZ authors had used headline CPI inflation (ex GST). Given all the noise in the latter series – eg changes in taxes and government charges – I wondered why the authors didn’t use, say, the sectoral factor model estimate of core inflation (the Reserve Bank’s favoured measure). It would be interesting to know whether the NAIRU results for the last half decade (when core inflation has been very stable) would be materially different. It might also be worth thinking about using a different wages variable. The authors use the headline LCI measure, as a proxy for unit labour costs. But we have actual measures of unit labour costs (at least for the measured sector), and the authors could also think about using, say, the LCI analytical adjusted series and then adjusting that for growth in real GDP per hour worked (a series that has itself been revised quite a bit in the last year). No model estimate is going to be perfect, but there does seem to be some way to go in refining/reporting analysis research in this area.

I have argued previously that the Reserve Bank should be required to report its estimates of the NAIRU, and offer commentary in the MPS on the contribution monetary policy is making to closing any unemployment gaps. I’d have no problem with the Bank publishing these sorts of model estimates, but I’d have in mind primarily something a bit more like the Federal Reserve projections, in which the members of the (new, forthcoming) statutory Monetary Policy Committee would be required to publish their own estimates of the long-run sustainable rate of unemployment that they expect the actual unemployment rate would converge to (absent new shocks or structural changes). The individual estimates are combined and reported as a range. No doubt those individual estimates will have been informed by various different models, but in the end they represent best policymaker judgement, not the unadorned result of a single model (end-point) problems and all.

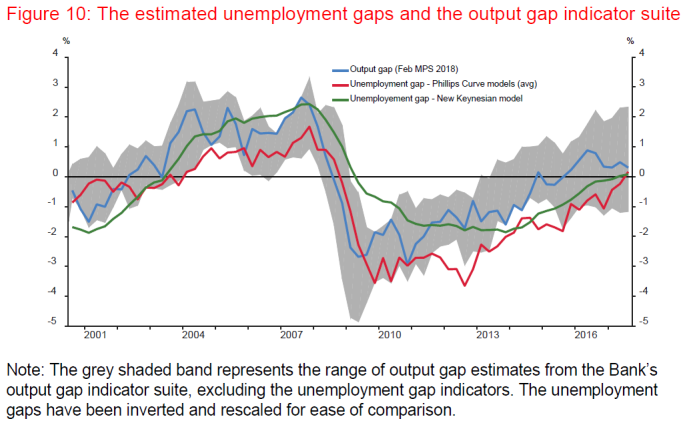

And finally, the Reserve Bank (aided and abetted by the Board) has always refused to concede it made a mistake with its (eventually reversed) tightening cycle of 2014 – sold, when they started out, as the beginning of 200 basis points of increases. The absence of any emphasis on the unemployment rate, or unemployment gaps, was part of what got them into trouble. In the latest research paper there is a chart comparing the Bank’s current estimates of the NAIRU (see above) with their current estimates of the output gap.

The tightening cycle was being foreshadowed in 2013, it was implemented in 2014, it was maintained well into 2015. And through that entire period, their unemployment gap estimates were outside the range of the output gap estimates.

We don’t have their real-time estimates of the unemployment gap, but we do have their real-time output gap estimates. They might now reckon that the output gap in mid 2014 (blue line) was still about -1 per cent but in the June 2014 MPS they thought it was more like +1.5 per cent.

The failure to give anything like adequate weight to the direct indicators of excess capacity from the labour market (ie the unemployment rate and estimates of the NAIRU) looks – as it felt internally at the time – to have contributed materially to the 2014 policy mistake.

(In this post, I’m not weighing into the specific question of what exactly the level of the NAIRU is right now, and the Bank does emphasise that there are confidence bands around its specific estimates, but I’m aware that is also possible to produce estimates in which the current NAIRU would be 4 per cent or even below.)

Spoonley is beating the drum for more migrants. He fails to mention that real wages in tourism and hospitality are falling (24.5% between 1979 and 2006).

i.stuff.co.nz/national/102243731/here-are-some-of-the-jobs-that-kiwis-

LikeLike

https://i.stuff.co.nz/national/102243731/here-are-some-of-the-jobs-that-kiwis-cant-or-wont-do

LikeLike

I can understand the linked article more easily than the NAIRU concept. For once there was plenty of sense from Prof Spoonley so long as you accept his definition of a ‘skill’. In particular his being reported as saying we “are too reliant on immigrants”. Every time he identifies an area of our economy that is dependent on immigrants it clearly identifies an area of our economy where NZ has a problem. You can’t complain about Paul Spoonley when he is the messenger but it is our government which plasters over the problem with more immigrants.

NAIRU: the post was very heavy going today. The concept seems to be that when you need workers and there is high unemployment all goes well with the economy but with low unemployment levels it makes sense that a demand for more workers will lead to general wage inflation which may not be good for the economy and specifically for price sensitive export businesses.

If NAIRU is an attempt to identify the point where high unemployment changes to low unemployment then I wonder if a single figure is relevant. Doesn’t a demand for workers have a different effect depending where and how the demand occurs. ‘Where’ applying to both physical location and employment type. A surge in demand for timber workers in Northland is not going to effect the economy the same as a demand for the same number of workers in Auckland to fill teaching and medical roles.

My mental image is of getting a stew to simmer; apply heat too quickly and it burns at the bottom while looking OK at the top.

LikeLike

He is arguing for support for industries which can only pay 3rd world wages?

…………

Spoonley said 30 or 40 years ago, most horticultural jobs would have been filled by locals doing seasonal work, but there are no longer enough locals to meet the demand.

……

30 or 40 years ago the Government started an agenda to diversify the population. This involved back filling with migrants when the NZ economy wasn’t so healthy and the “best and brightest” headed overseas.^

…..

Maybe migrants displaced Kiwis?

Globalization breaks the social contract?

LikeLike

Samoan people have largely been used to fill the needs of horticulturalists and fruitgrowers as seasonal fruitpickers, largely in the fruitgrowing regions. Whether they enter into NZ on temporary work visas is not known, but is assumed. We do know the Samoan people are not considered as part of the annual Pacifica 1000 draft from Tonga, Niue, and Fiji

From the available Census data the Samoan Population in NZL is

NZL Samoan population 2001 = 115,000

NZL Samoan Population 2006 = 131,100

NZL Samoan Population 2013 = 144,100

Most of those are located in Auckland with the greatest concentration in South Auckland

It appear that many of the seasonal fruitpickers do not return at the end of the fruitpicking season and find there way into South Auckland and stay there. The following year there is a need for another influx from Samoa for the next fruitpicking season which in turn will migrate north to South Auckland to make way for next years intake

How else can the 29000 increase in 12 years be accounted for.

The same situation repeats itself for international students coming to NZ and filling the menial service jobs, then as they graduate they move to Auckland and make way for the perpetual never-ending need for low-skilled workers

Total resident population of Samoa is 195,000

LikeLiked by 1 person

There is a specific Samoa quota as part of the residence approvals programme. Also the census numbers will mostly be NZ-born people on Samoan descent. Birth rates that are probably above average, and intermarriage (and the ability to list multiple ethnicities) probably explain the increase you cite (just over 2% pa),

LikeLiked by 1 person

Samoans are no problem. If Samoa disappeared below the ocean and they all came to NZ it wouldn’t change NZ greatly. Not like my ancestors arriving 200 years ago nor compared to say 1% of the population of [China India Indonesian Russia] (take your pick) arriving. Simple matter of numbers.

Using PI fruit pickers makes sense; good for us and good for them and good for the countries they come from. Since they arrive for short periods they would not be appearing in our immigration statistics because we define immigrant as intending to stay for over a year. I do know the devil would be in the detail; I cannot speak of other PI countries but having a squad of Papua New Guineans arriving would have to be organised very carefully – there can be serious cultural differences – personally I would use church groups and have both NZ contacts in PNG and PNG contacts in NZ (the same group leaders arriving year after year). A couple of months NZ minimum wages goes a very long way in a PNG village.

LikeLike

When is someone from the MSM going to show independence and integrity and critique globalist Paul Spoonley?

LikeLike

As long as our industry focus remains targetted at service then the only way that companies generate a profit is to keep lowering the cost of servicing the revenue base. MacDonalds is trying hard to get productivity by increasing revenue, getting the customers to clean up the tables and self ordering on automated push button ordering systems and reduction in the number of labourers.

BurgerKing next door has a different business strategy by reducing attendant labour and getting customers to queue a little longer for their food. Lower revenue but higher margins. Of course both outlets use a lot of international student and migrant labour to keep the labour costs lower.

LikeLike

Actually at BurgerKing, you queue to order with only 1 order attendant available to take orders. You then also queue and wait for your food to be served. But to make your wait time more worthwhile, they give you unlimited access to the the beverage machine and you collect your cup when you complete your order. You burn some wait time selecting your beverage of choice, topping up with ice and perhaps mixing a number of different flavours to achieve your own unique flavour and then you wait for your food to be served up but with a cold unique flavoured drink to happily sip away and once your food is ready you can do a top up with another flavour and have another full cup of beverage to finish your meal and then another top up before you leave.

But knowing the high sugar content of these beverages you would usually top up with a full cup of ice and use very little beverage in the top up. Smart marketing and low tech but increased wait time.

LikeLike

I had a look at that NAIRU paper and understood maybe the first and last pages!

I did note they said this:

“The unemployment rate is only one measure of slack in the labour market

and should be supplemented with other indicators and analysis.”

For me, this is surely the key to why we have so little wage and CPI inflation and such a “low” unemployment measure. In fact there are a lot of people underemployed. It certainly resonates with what I see around me. And this goes the world over….

But I am afraid that the middle sections were beyond my small brain until I improve my maths! So I thank you, as always, for giving a good layperson’s summary.

I find the NAIRU concept morally abhorrent. That a certain proportion of the population AND THEIR CHILDREN must be sacrificed to poverty and misery in the name of controlling inflation via disciplining labour seems like a political choice to me rather than some natural law. Surely if we can send spacecraft to Mars, we can find a better way to run our economy so that is unnecessary.

We use an unemployed buffer stock to control inflation and forget these stock are not stock they are people.

LikeLike

the RBA piece is much more accessible (it was written for a lay audience, while the RB one was aimed at a more technical audience.

On your second to last para, if what you wrote was an accurate description I’d find it morally abhorent too. But it isn’t. The NAIRU, or natural rate, is really determined by that whole mix of structural factors that have nothing to do with monetary policy. For example, unemployment benefits are probably a good thing, but they do tend to have the effect of raising the average or normal unemployment rate – search is a little less urgent than it otherwise would be. Minimum wage laws have similar effects. And, on the other hand, when there are more young people in the workforce, the normal or natural rate of unemployment tends to rise too, just because young people turn over jobs more frequently, and are likely to count as unemployed for a short-term between each.

So whenever we look at micro reforms affecting the labour market, one thing – not the only thing – to think about is the implications for the natural or normal level of unemployment,

In this context, what I regard as fairly morally abhorent is a central bank running monetary policy in a way that holds the actual unemployment rate above their own estimates of the NAIRU for the best part of 9 years. That should be inexcusable, and simply not tolerated. Except that NZers – leaders (Labour and National) and voters, RB Governors and Boards – did.

LikeLike

The fact that the two methods give such different answers a lot of the time suggest we don’t really know. One would think that as a matter of human compassion, a reasonable step (for a CB who had been below the inflation target for some time) would be to decrease the unemployment rate until tangible wage pressures started to be seen. The white of inflation’s eyes, so to speak.

LikeLike

Yep. Not since 2009 has either measure of the unemployment gap suggested the U rate had dropped materially below NAIRU. As I just noted to another commenter, that should have been inexcusable. But we – leaders and voters – excused it.

LikeLike