I’m not going to write much about the Productivity Hub (Productivity Commission, MBIE, Treasury, and Statistics New Zealand) conference yesterday on “Technological Change and Productivity”. Not all of it was even about productivity, not all of it was even relevant to New Zealand (there was a genuinely fascinating presentation from a US academic on the economics of wind and solar power, which must matter a lot if half your power is generated from fossil fuels, but rather less so in a country where 90 per cent of power is hydro-generated). And there was lots of focus on micro data on firm (or agency) level productivity, even though no work in that area has yet been shown to shed much light on the large gap between economywide average productivity in New Zealand and that in most other advanced OECD countries. But the “Reddell hypothesis” did get a (positive) mention from the platform, when the Productivity Commission’s Director of Economics and Research, Paul Conway, reprised some of the thoughts from his 2016 “narrative”, highlighting the likely importance of the macroeconomic symptoms: persistently high real interest rates (relative to other countries) and a high real exchange rate. Conway suggested that we should focus much more on bringing in highly-skilled migrants, and that if that led to a reduction in total numbers that might well be a good thing. With 47 MBIE people among the 200 or so (mostly public service) registrations, I don’t suppose that proposition commanded universal assent, but there wasn’t any further open discussion.

I couldn’t stay for the final session, but fortunately that speech has been made widely available. The Minister of Finance gave an address on “The Future of Work: Adaptability, Resilience, and Inclusion”. At one level, I was pleasantly surprised: there was more about the productivity challenges New Zealand faces (our overall underperformance) than I’d expected. And if I’m sceptical about the Treasury Living Standards Framework, and attempts to build policy around “well-being”, I couldn’t really disagree with the thrust of this line from early in the speech

Improving productivity is key to improving wellbeing. By producing more from every hour worked, businesses become more profitable, incomes rise, and workers’ wellbeing rises as time is freed up and purchasing power rises.

And it was good to have the new Minister of Finance remind us that productivity growth (lack of it) has been a longstanding problem in New Zealand. Although even then he seemed inclined to underplay the problem: for example, basically no productivity growth at all for the last five years. And he noted that GDP per hour worked is now around “20 per cent below the OECD average”. But since the average includes places like Turkey and Mexico, and a group of countries (ex eastern bloc) which weren’t market economies at all 30 years ago, it might be better to highlight the point I made in yesterday’s post: for New Zealand to catch up with the G7 economies as a whole, we’d require a 50 per cent lift from current levels (assuming those countries had no growth at all), and to match that group of highly productive northern European economies (France, Belgium, Netherlands, Germany, Switzerland and Denmark), we’d need more like a two-thirds increase. Even to catch Australia – which lags some way behind the OECD leaders – would take a 40 per cent increase in economywide productivity. That lost quarter-century won’t be regained easily.

But it is one thing to recite these numbers (early in one’s term as Minister of Finance). As even Robertson put it

I am most certainly not the first New Zealand politician to both highlight the challenge of low productivity, nor to say that we will address it. So the proof will be in what we actually do.

And what is on that “to do” list? And that is where it gets a bit disconcerting.

There are a couple of the reviews underway

Our Tax Working Group and the reforms we are making to the Reserve Bank Act are an important part of setting the path to a more productive economy. That focus on improving productivity is at the heart of the terms of reference for both these reviews.

No serious observer believes that the sorts of changes foreshadowed for the Reserve Bank Act – desirable as the general thrust might be – will make any difference whatever to the trend level of productivity in New Zealand. Monetary policy just isn’t that potent. As for the Tax Working Group, a (limited) capital gains tax might, or might not, be a good idea but I’d be surprised if anyone believed it would make a very material difference to overall economic performance (and, after all, much of the TWG documentation has a prime focus on fairness). For all the talk about “too much investment in housing” recall – as the Minister doesn’t in his speech – that a key element of government policy is building lots more houses. Resources used for one thing can’t be used for other things.

What else is the government planning?

The government has committed itself to the goal of a net zero carbon economy by 2050. This is an essential shift for New Zealand away from an economy that hastens climate change to one that is more sustainable and develops New Zealand’s strategic advantages.

We will need to ensure this is a just transition where affected industries and communities are given the support to find new sustainable growth opportunities.

Again, you might or might not think this is a worthwhile goal, but it isn’t going to lift economywide productivity relative to what would have happened without the net zero goal. Even the Minister is here focused on smoothing transitions, minimising disruption.

Then there is skills.

The Future of Work was the catalyst for our three years’ free training and education policy. One of this Government’s key policies is to provide one year of free post-secondary education or training, gradually progressing to 3 years by 2025.

So in a country where the OECD data suggest that the skill levels of New Zealand workers are already among the very highest in the OECD, the government is going to spend rather a lot of money (all funded by taxes, with their deadweight costs), in the expectation that a marginal cohort of people who would not otherwise have invested in formal training/education will now do so. Most of the immediate gains will go to people who would in any case have gone to university (or done other comparable training) – I’m expecting my kids to be in that category – and most of the people who take up formal training who otherwise would not have done so, are likely to well below the leading edge in terms of productivity potential. If there are gains at all economywide – which seems unlikely, but I’m open to persausion – they will almost certainly be pretty small. It is mostly a middle class welfare policy, not a productivity policy.

Then there is regional development policy

A major example of this is the Provincial Growth Fund developed as part of our coalition agreement with New Zealand First. This will see significant investments in the regions of New Zealand to grow sustainable and productive job opportunities.

The details of the Fund are to be released shortly and will provide some of the most significant development of our regions in decades. These will be driven from the ground up, with the Government as an active partner.

If it ends up less bad than a boondoggle we should probably be grateful. It isn’t the sort of policy that has a great track record, and it is hard to be optimistic that one new minister – with a vote base to maintain – is going to transform the sort of flabby thinking around regional development presented at Treasury late last year. At very very best, it is all rather small beer. Recall that we need a two-thirds lift in economywide average productivity to catch those northern Europeans.

It goes on

It is my strong belief that the most critical element to New Zealand succeeding in the Future of Work is a renewed social partnership between businesses, workers and the government.

If we look at Germany as an example, union members often sit on company boards as part of the decision-making process, ensuring that employee wellbeing is considered alongside high-level corporate profit and financial targets.

One of my goals as Minister of Finance is to develop this new partnership at a system-wide level to promote a combined work stream on how we can apply these lessons to other industries and sectors.

Maybe the Minister doesn’t see this sort of stuff mostly affecting productivity performance. But if not, what will?

Perhaps R&D.

In the Coalition Agreement with New Zealand First we have set a target of hitting an R&D spend of 2% of GDP in ten years. That’s more than a 50% increase in R&D investment relative to GDP over that time and will make a significant contribution to improving our productivity.

Officials say that this is an ambitious goal. We believe this can be done, with the Government incentivising such vital work by the private sector.

Minister for Research, Science and Innovation, Megan Woods, has already begun work on overhauling New Zealand’s R&D regime, with Ministers set to discuss officials’ initial findings later this month. We are committed in the first instance to restoring R&D tax credits to give firms some certainty about their investments.

But, as with earlier comments the Minister made in his speech about relatively low rates of business investment, there is no suggestion that the government has thought about what it is in the economic environment that leaves private businesses – pursuing profit opportunities where they find them – unwilling to spend more, whether on R&D or investment.

It was interesting that the Minister of Finance chose to highlight comparisons with Germany in his speech. As I’ve pointed out in an earlier post, Germany doesn’t have an R&D tax credit (actually of those successful northern European countries I highlighted earlier, neither does Switzerland) – although the senior OECD official whose seminar I attended the other day, who didn’t seem wildly enthused about the merits of such tax credits, did note that the German government is under business pressure to introduce such a scheme because, eg, France and the Netherlands have them.

There are stories galore about what gets claimed for under R&D tax credits, and one person at the seminar the other day indicated that the Australian government is currently looking to wind back its R&D tax credit, having realised that a significant amount of money is being rorted. If free tertiary education is (largely) welfare for middle class parents and their children, R&D tax credits look like welfare for the owners (often foreign) of businesses. The R&D spending already happening would, presumably, have taken place anyway, so if there is to be a tax credit in respect of that spending it is pure gift (on top of the advantage of being able to immediately expense anyway). There will be significant incentives to reclassify some activities as R&D that weren’t previously (because there was no advantage to doing so). Some of that will bring to light genuine R&D spending that wasn’t previously visible – slightly tongue in cheek, the OECD official noted this was one advantage of R&D credits. Other spending won’t really be R&D at all, and IRD will be engaged in a constant battle to hold the line. And perhaps there will be some additional R&D work undertaken that wouldn’t otherwise have occurred. But surely – a bit like the increased teritary participation that will flow from fee-free study – most of that will be, almost by definition, the least valuable, most marginal, activities; the stuff not worth doing without a subsidy?

It is, frankly, a bit hard to believe that even the best R&D tax credit – and I gather MBIE officials are working hard to limit any abuses and wasteful transfers in the forthcoming tax credit – will be a transformative part of the story.

Let’s go back to those northern European countries, with a slide from the OECD official’s presentation:

France – third bar from the left – has some of most generous government support for business R&D of any country in the OECD database, including a generous tax credit. That support has materially increased in the last decade, but it was still fourth highest in 2006 (the white diamond). Germany (DEU) has low overall government support, and no R&D tax credit at all. These are both advanced industrial economies, situated right next to each other, with lots of trade between them. And here is OECD data on the respective levels of real GDP per hour worked.

Identical at the start, identical at the end, and never – through the whole period (Mitterrand, absorbing East Germany or whatever) – any very material deviation between the two lines. It is the sort of relationship – univariate and all – that makes it more than a little hard to take seriously suggestions that introducing an R&D tax credit here will make any material difference to our relative productivity performance.

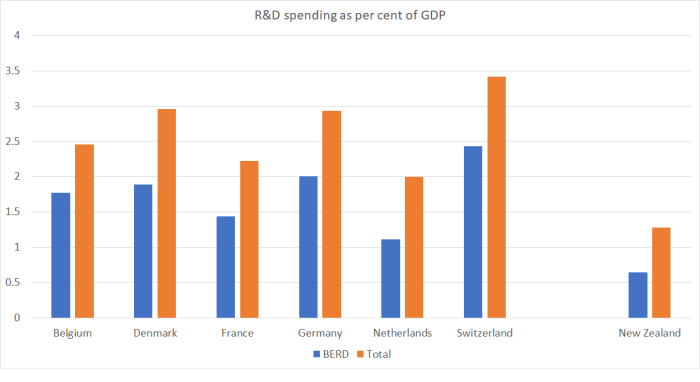

And here is the OECD data (for 2015) on R&D spending in each of those six highly productive northern European countries, and New Zealand. “BERD” is business expenditure on research and development.

Remember that Germany and Switzerland are the two of the northern European group that don’t have R&D tax credits, and provide little direct government support to business R&D. I’m not suggesting any sort of perverse relationship – a lot probably depends on the specific sectors businesses in particular countries concentrate on – but it should at least be a little sobering to reflect that the two countries in that grouping with no R&D tax credits have higher rates of business spending on R&D than any of the other countries in the group (even with all the incentives that such credits create to classify spending as “R&D”). One might wonder if the big French incentives – increased in the last decade – might not have been sold on the basis on “we are lagging behind Germany in R&D spend” and need to “do something” to catch up.

Mostly, a reasonable hypothesis still looks to be that firms will invest (including spending on R&D) when it appears to be profitable for them to do so. If so, it might be better to spend some more time understanding what holds firms back – addressing issues at source if possible – rather than just throwing more government money at a symptom. There isn’t much sign the government has done anything more than highlight a few trendy symptoms, rather than really engaging in an integrated narrative of New Zealand’s economic performance. The Minister of Finance concluded his speech yesterday

I want us to re-write our productivity story, so that New Zealand becomes a leading example of a sustainable and productive economy in which everyone gets a share of economic success.

It is a worthy aspiration – shared, no doubt, by a long line of predecessors stretching back decades – but there is little sign of the sort of serious thinking – or even engagement with the full range of symptoms (eg weak export share, high real interest rates, high real exchange rate, physical remoteness and yet rapid population growth) – that would provide much reason for confidence that they might yet devise an effective strategy to respond to the specifics of New Zealand’s situation.

And since a common response whenever I write along these lines is “but what would you do differently?” here are links to a version of my story given to a business audience , a version given to the Fabian Society, a more recent version to a general audience. In the margins of the conference yesterday, one person commented that he thought one problem was that few officials had read my original paper, prepared a few years ago for a Reserve Bank/Treasury-hosted conference, which puts the basics of the argument in a standard two-sector (tradables and non-tradables) analytical framework, here is the link to that paper too.

Pretty much agree with every single point, with the exeception that I am probably a bit more hopeful about the impact of a small, well-designed R&D tax credit, based on my experience of the Australian scheme. I can only hope Robertson is planning to do more stuff than he is letting on. (Lord knows talking about macroeconomic imbalances and productivity isn’t going to get him on the morning chat shows).

LikeLike

Given that these are mainly service related industries. The lower hours worked equates to more people needing to work. My mother has 4 visits a day to car for her at home. The government has contracted an Australian company to provide the cleaning and grooming service. Each visit we usually see different people working. 4 visits a day by 2 people at an hour each. Rather than providing my mother with 1 person for an 8 hour day. She gets 8 different people that work part time. I guess this means more migration rather than less.

LikeLike

In summary, your recommendation for higher productivity falls back onto a single line ie Change the immigration target back from 50,000 per annum to 15,000 per annum and that will fix our productivity problems as we are at best a primary producer and therefore land dependent and because we are too isolated that is about it for us as a nation.

LikeLike

That is the key element of a prescription. Of course, there is plenty of other good stuff I think we should be doing (and dumb stuff we should stop doing), but even in aggregate most of the plausible stuff in those categories won’t add up to enough to make very big differences to the gap between average productivity here and that in those northern European countries. We could cut capital income taxes, impose congestion pricing, fix land supply and insfrastructure finance, pull back on quite bit of the regulatory burden and I doubt it would close more than 10-20% of the gap.

(Those precise numbers are a cut from 45000 residence approvals, to a range of 10000 to 15000 per annum).

LikeLiked by 1 person

A country like Germany has access to a large market. Its companies therefore adopt a high volume and low margin strategy. Low margin means that you can either sell at a lower price to obtain the volume or you can incentivise via bonuses and higher wages for less hours worked.

NZ is a small and isolated market which means that to be successful companies must adopt a low volume and high margin strategy. Sell less, and put downward pressure on costs to get higher margins.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yesterday’s post about NZ productivity per capita left me too depressed to contribute and today’s post about our governments’s approach to solving the problem is little better.

There seems to be a problem with how politicians and the public think about these kind of issues. They start with some evidence that a particular action gives a good result and them jump to ‘more will be better’. So activities that I very strongly approve of: tertiary education, skilled immigration, investing in R&D are ruined by excess. My doctor has me on blood thinners; he emphasises how they they reduce my risk of a heart attack but he doesn’t say “its a life saving pill so take as many as possible” in fact he goes to great lengths to warn me of the dangers of an overdose.

Switzerland seems to be doing well; certainly economically. It has traditionally had low immigration, about half the number of university students and you say no government encouragement of R&D (well other than letting successful businesses keep some of their profit unlike say communist regimes). It does look closer to potential markets than NZ but the geography is not that friendly so how do they export more manufactured goods to China than much larger OECD countries?

Has NZ loosened the ties between business and worker excessively? Traditionally an average worker stayed in the same business for a lifetime often with brothers and sisters and children working with the same employer. That must have helped focus workers minds on long term success for the business. NZ has made it very easy to employ contractors and low value immigrants and neither will have the same level of commitment to their employer. Just possibly there is something to be said for worker representatives on the boards of businesses. Or have we just lost too many of our large scale employers other than the public service?

LikeLike

I’d say Switzerland’s geography is pretty ideal – surrounded by several big rich countries (Germany, France, Italy) and close to other rich smaller countries (Austria, Belgium, Netherlands, Denmark. Throw in the UK, Poland and Spian and there are probably more rich people close by that anywhere else in the world (places like NY might be getting close, but the western US and Europe are a long way away). Having said all that, as I’ve pointed out, having started with very high productivity 50 years ago, Switzerland is now at the bottom of that group of six countries.

Be careful of those employment tales. There were people who spent a career with one employer in days gone by, but there was a huge amount of casual labour too. I’ve seen statistics – a few years ago now admittedly – suggesting that the median employee today might spend more time with a single employer than people did say 50 or 100 years ago (fewer 40 year people perhaps, but presumably more 5-10 year people?)

I don’t have a problem with worker reps on boards, if companies themselves decide it is mutually beneficial. from memory ,most German firms have two tiers of boards (vague memories of studying industrial relations models decades ago).

LikeLike

Swiss exports to China/Hong Kong exceed their exports to France or Italy. So geography is a factor but not the only one.

LikeLike

Indeed, altho (a) exports to Europe well exceed exports to Asia or the Americas, and (b) when a country’s largest export is gems and precious metals (almost 30%) almost none of which originate there (Israel is similar) the data get harder than usual to interpret.

LikeLike

Enlighten us what Switzerland exports to China.

LikeLike

65% are pearls, precious stones, metals, coins

https://tradingeconomics.com/switzerland/exports/china

(clocks and watches 5%)

LikeLike

Well the answer is https://tradingeconomics.com/switzerland/exports/china

27.5 billion

Pearls, Precious stones, metals and coins, 65% of exports

Pharmacuticals 13%.The balance being lots of small stuff.

Switzerland’s Gold Exports To China Surge To 158 Tons In December

26, January

Switzerland’s Gold Exports To China Surge To 158 Tonnes In December

https://news.goldcore.com/us/gold-blog/switzerlands-gold-exports-to-china-surge-to-158-tons-in-december/

Meanwhile China exports to Switzerland

4 billion

Easy I guess to export gold. No labour hours required.

Probably a lot of Nazi gold gong to be melted down once more.

Or maybe tax haven gold sold to pay Trumpy his taxes.

you think.

LikeLike

I wonder if we are making too much of geography and its effects on trade in NZ. Containerisation has decreased trading costs significantly over the last 50 years. Moreover, the costs of communication has come down to virtually zero

A shipping cost estimator comparing the cost of shipping from Auckland to world markets does show it is more expensive to ship goods from NZ than from locations with higher volumes such as Singapore. But depending on the value of goods, the percentage costs not seem a significant barrier. If our perishable agricultural goods can be exported competitively, I am wondering why exporting higher value goods is a problem.

LikeLike

I have just re-read your excellent article “Large-scale (non-citizen) immigration to New Zealand has been making us poorer” – it needs to be revisited monthly just to remind us all

“The last bus stop before Antarctica”

“Business owners constant clamour is “we need immigrants to cover skill shortages, and the economy would fall apart if we changed policy”. Employers have been

running this line for 100 years now – every decade (I have quotes from the 1920s). And yet even with really large migration inflows, somehow the shortages are never met, and all the time NZ’s performance has been going backwards. Somehow other countries manage – and prosper”

I’m having some concerns about the Coalition Finance Minister whose think big thought bubble project is to re-engineer the workforce to work 400 hours less per year followed by the Coalition backing away from it’s immigration reforms in “Government puts handbrake on immigration pledges” at https://www.newsroom.co.nz/2018/01/30/79390/government-puts-handbrake-on-immigration-pledges

I am apolitical – didn’t vote for either Labour or National

LikeLiked by 1 person

The never-ending demand for exploited work-visa victims

It only needs one to start the process then the ripple effect takes control

If a business recruits and exploits migrant labour at $2 per hour and the intending work-visa holder then has to pay $20,000 to the business owner then that business is far more profitable than its nearest competitor next door. Can and will cut prices. The now struggling competitor has to do the same thing which then squeezes the 3rd guy down the road who then squeezes the 4th guy and so on ad infinitum until they are all in the same boat all doing the same thing, competing against one another – they are back to where they started

Now they all need a never-ending supply of exploited temporary work-visa victims to stay in business

NZ Society is much the poorer for it and has to pick up the tab in infrastructure, schools, health, welfare etc

LikeLiked by 1 person

Iconoclast: my daughter will be looking for work when her baby is a little older. A few years ago she was an assistant manager at Domino Pizza so working in Birkenhead which is our nearest shopping centre would make sense.

See: http://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=11990563

which includes “” Gie Balajadia of 3Kings Filipino Cuisine in Birkenhead”” and “”the judge said the conditions of the victims was not far removed from a modern-day form of slavery”” and “”INZ approved visas for five victims – all chefs from the Philippines – after receiving offers of employment, letters of support and job descriptions for them to work at the restaurant. Although contracted to work for a minimum of 30 hours per week at an hourly rate of $16, they were all either not paid at all or paid for far fewer hours than they worked.””

and see: https://www.stuff.co.nz/business/76647855/masala-indian-restaurant-chain-assets-frozen-in-high-court-order

which under a photo of the old Masala restaurant Birkenhead includes “” sentenced on immigration and worker exploitation charges after former staff revealed they had been paid as little as $2.64 an hour for working up to 11 hours a day.””

Can you recommend a suburb to my NZ citizen daughter where employees are not treated as slaves?

Maybe I am from a different planet but when slavery is occurring because of failures by MBIE I really don’t want to know they had 47 employees attending a conference. Sack all of them and employ some labour inspectors or at least consider redefining ‘skilled’ to mean very well paid.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Funny you should ask that question

I have working for me a 35 year old who is a kiwi who originally trained as a chef and went to Perth WA where he ran a restaurant kitchen. He eventually gave up and returned to NZ because the owner of the restaurant kept holding him responsible for the profitability of the restaurant. After a couple of years he went to Unitec and did an Arborial and Forestry course. He is gold. I don’t have to tell him what to do. He has a 30 year old mate from that Unitec course who got a job with an arborial company as soon as he finished the course. He has just tossed it in as his boss was treating him as a 15 year old apprentice and working him on 4 day weeks and short days and having to run his own transport to jobs. An added factor has been the injuries he has suffered including serious back problems. He has been talking about going to AU to get some work. Today he announced he has enrolled at Unitec to do s cooking course. Gobsmacked, I asked him – “don’t you read the papers” – telling him about the 600 chefs coming into NZ each year on $2 per hour – where did he think he was going to get a job?

LikeLiked by 1 person

It takes 2 set of hands to clap. I am pretty sure both parties had an agreement and both are willing participant. The contractual terms are low wages plus a path to residency. This would have been between 2 willing participants. Sure he did not pay the minimum statutory wage but this is not a criminal offence. It should have been settled in a civil court.

LikeLike

Of course it “takes two hands to clap” as you put it. One case came to light because the exploitation was so extreme that “”… the victim named in the exploitation charges reported his plight to the Philippines Consulate””. Most will never come to light.

It is quite possible the victims in this case and other cases are more saintly than my unemployed daughter; I don’t know. One can feel for them and also all their fellow citizens who experience exploitation back home and dream of a decent life in NZ. However that is not an adequate reason for members my family to suffer employment difficulties simply because foreigners are willing to be exploited. This exploitation is criminal but a crime that is usually undetected. I’m baffled that the population of NZ are willing to tolerate ” a modern-day form of slavery” facilitated by the callous incompetence of our department of immigration.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Is the productive problem in NZ, a reflection of the lack of change in major industries? NZ main export earners remain agricultural, a commodity-based business. 50 years in the aftermath of WW2 where many countries had depressed manufacturing capacity and still had food rationing, NZs exports received great prices.

I want to compare Denmarks top 10 export categories to NZs

Machinery including computers: US$12.8 billion (13.6% of total exports)

Pharmaceuticals: $12.5 billion (13.3%)

Electrical machinery, equipment: $8.8 billion (9.4%)

Mineral fuels including oil: $4 billion (4.2%)

Optical, technical, medical apparatus: $3.9 billion (4.2%)

Meat: $3.6 billion (3.9%)

Furniture, bedding, lighting, signs, prefab buildings: $2.8 billion (3%)

Fish: $2.6 billion (2.8%)

Vehicles: $2.4 billion (2.6%)

Dairy, eggs, honey: $2.4 billion (2.5%)

New Zealand

Dairy, eggs, honey: US$10.2 billion (27.6% of total exports)

Meat: $4.7 billion (12.7%)

Wood: $3.3 billion (9%)

Fruits, nuts: $1.9 billion (5.1%)

Beverages, spirits, vinegar: $1.4 billion (3.7%)

Fish: $1.1 billion (3.1%)

Cereal/milk preparations: $1.1 billion (2.9%)

Machinery including computers: $978.6 million (2.6%)

Modified starches, glues, enzymes: $884.6 million (2.4%)

Miscellaneous food preparations: $873.2 million (2.4%)

Denmark has managed to change its economy from an agricultural to industrial based one. NZs exports remain largely unchanged over the last 50 years. Is complacency an economic concept, I wonder?

How do we change the paradigm? I remember 20 years ago, in the age of rising Asian tigers, there was a segment on the Holmes show, an economist was asked why NZ can’t have the growth rates of Singapore or South Korea. It was explained at the time that all this was catch up growth and NZ having a similar trajectory was unrealistic. In many aspects, these tiger country have caught up and are exceeding NZ’s wealth and performance now.

Can we now catch up and learn from Denmark or Asian tigers? I think in hindsight, NZ has wedded itself to conventional orthodox economics too long allowing the hollowing of key industries. Perhaps its time to learn from Singapore and follow heterodox economists such as Ha-Joon Chang.

LikeLike

From 1960 to 2016 Denmark’s population grew by 25.1% and New Zealand’s by 97.9%.

Looking at your list of exports I can see why Denmark’s may have grown with several of those new businesses needing employees but judging by your list of NZ exports I do not see why we need more people. In fact some of those businesses such as Meat exports almost certainly need far fewer employees now than they did in 1960.

I reluctantly admit it, the Reddell thesis seems to get stronger the more it is considered. The half of the NZ population added since 1960 (including my family) are just doubling the mouths to feed from the same sized pie.

LikeLike

That’s the problem, our economy hasn’t changed from the 1960’s. Immigration is a separate issue but related issue. If the economy hasn’t expanded into new areas, the corollary is more people results in dividing the economic export pie into smaller slices.

I see little reasons why New Zealand could not have expanded into areas where Singapore or Denmark have. To build new industries and the skill and capitals are not indigenous imports knowledge and people are essential. But importing people without a coherent strategy has been a problem. Singapore is trying to build a biotech industry currently which is government directed. Small countries need activist government and can not get away with US-style laissez-faire governance.

Behavioural economics applies psychological insights into human behaviour to explain economic decision-making. That is where I think the issue lies in NZ. As Michael said, there is little effort made or interest in addressing our productivity issues on the national level. Doesn’t that tell you all you need to know why NZ languishes?

LikeLike

Wrong!!. The problem with primary production is the transfer of wealth to the masses. Back then the wealth was in the hands of a few farmers and to distribute that wealth, the tax was at 60% and there was death duties. There is a limit in terms of the land availability and we have reached peak primary production a long time ago. Currently with 10 million cows we have already crossed the limits perhaps by a 50%. Agricultural returns only around 30% of export GDP back to the masses. Industrial production also has a low level return to the masses as a lot of materials are imported. Cows are not just grass fed. They also require palm oil kernals imported as secondary feed. Chemical wash by the tonnage to manage pests, lice, ticks, disease.

High productivity in NZ has always been questionable because it relies on mathematics that excludes counting the livestock. One cow eats and creates unmanaged wastes to the tune of 20 people. With 10 million cows, NZ is currently feeding and not managing the waste production of the equivalent to 200 million people. Export GDP is only around $15 billion. Compare that with 1.5 million Aucklanders that create GDP of $75 billion. Of course a Korean government heavily subsidised Samsung company with 308k workers create sales of $350 billion.

Primary production is not going to deliver the productivity no matter how much we hark back to the old days.

LikeLike

2 million new Kiwis to handle 4 million tourists – assuming there were no tourists in 1960. If a typical tourist stays 2 weeks that is 160,000 tourists or 12.5 new inhabitants per tourist. No wonder our productivity is so low. Surely by retraining the numerous people in our rural sector displaced by technology we could have achieved sufficient tourist support staff with minimal immigration.

Personally I could live with doubling our population if the new businesses David is touting existed. But they did not arrive – investors (even me) preferred to put our money into property.

LikeLike

Every tourist coming into New Zealand should be required to contribute $200 into a “Pure Clean Green Fund” that is used for cleaning up our coastlines and coastal waterways and roadsides – alternatively they get in a speed queue, take a ticket, and go where directed and spend 2 days of their stay as a member of a clean-up crew – cleaning up all the plastic waste and other rubbish

http://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=11995053

LikeLike

Bob, there are currently only 1 million migrants or 25% of NZ population who are overseas born in NZ not 2 million. That is to mainly replace the 1 million New Zealanders that currently reside overseas(600k in Australia) who have chosen to abandon NZ.

LikeLike

Sorry I agree with david in aus and disagree with Micheal and with Bob Atkinson

LikeLike

Mine was a simple description of what happened – people in and no exports out. That is hard to disagree with.

If NZ had produced a Samsung, a Sony, an Apple, an Amazon and the population had tripled and the wealth reasonably distributed and we had the GPD per capita of Denmark I’d be happy.

Those kind of businesses were produced by exceptional people. NZ is still considered a decent place to live; we might just be able to change our immigration policy defining high skill as equivalent to a PhD in computer science from Calcutta and then with some serious PR we might succeed. However our government still thinks low paid pseudo-chefs will trigger an economic revolution despite having been proved wrong year in, year out. They are reluctant to bite the bullet and stop un-skilled and low-skilled immigration because house prices will drop, latte in the coffee shop will go up and young Kiwis will need practical training instead of academic classroom prowess.

LikeLike

Unfortunately 4 million tourists need to be cared for. A PHD in computer science for the few jobs available in Xero is fine. But the hundreds of thousands of jobs are not for computer scientists but for the service needs of tourists.

LikeLike

Bob, Denmarks population grew from 1.5 million to 5 million within about 72 years prior to 1972. They had tremendous growth before population growth started to slow down. It looks like we are just entering that growth phase but a lot slower than Denmark during those periods just prior to 1972.

LikeLike

Interesting analysis, your assessment is in some ways rather bleak. The comments on Robertson were dispiriting, rather than surprising.

I still wonder why it is that we find it so difficult to properly harness and develop our great innovative skills. Are there deep seated cultural issues and attitudes that negate this?

The comments on R&D were interesting. I wonder whether the difference between France and Germany might reflect some cultural/historical differences. My recollection maybe wrong, but France has long had a very centralised and directed economy. In many ways the classic intertwining of bureaucracy,politicians and businesses – large areas of the economy are either state owned or closely aligned. Indeed, France perhaps more than most European countries promotes national champions and through the EU props up the agricultural sector. Many commentators have commented on the core issues of the French economy. Whereas West Germany built a strong economy largely based on the Mittelstand with an emphasis on exports and quality, heavily dependent on smaller to medium size businesses occupying significant market niches worldwide. Not being an economist, I don’t know, but wonder what others think and what lessons for NZ might be drawn.

LikeLike

Whenever I discuss the sort of thing Michael Reddell talks about (with your average worker), the reply is like opening a box and reading what Mike Hosking has written. The narrative in the mainstream media is cauterised on the left (RNZ) where Paul Spoonley stalks and on the right where the BNZ and property developers lean on the editors.

LikeLike