I’m spending today in a conference organised by the Productivity Commission and various government departments on technological change and productivity. Yesterday afternoon I went to a seminar at the Productivity Commission at which one of the conference speakers, a senior OECD official, was speaking on technology, “innovation policy” etc. It had been billed as something that would address the huge gap between New Zealand average productivity levels and those in much of the rest of the OECD. In fact, it hardly touched on that issue at all, and much of the discussion had the feel of analysis and advice for the OECD grouping as a whole, and particularly its more advanced members (the speaker himself was Dutch), rather than for a laggard country.

For New Zealand the biggest challenge, by far, is – as it has been now for some decades – catching-up again. Decades ago we were at or near the frontier – economic frontier that is, rather than physical remoteness – with per capita incomes in the top 2 or 3 in the world. These days, probably a few New Zealand firms are at or near the frontier, but the overall New Zealand economy lags quite badly behind.

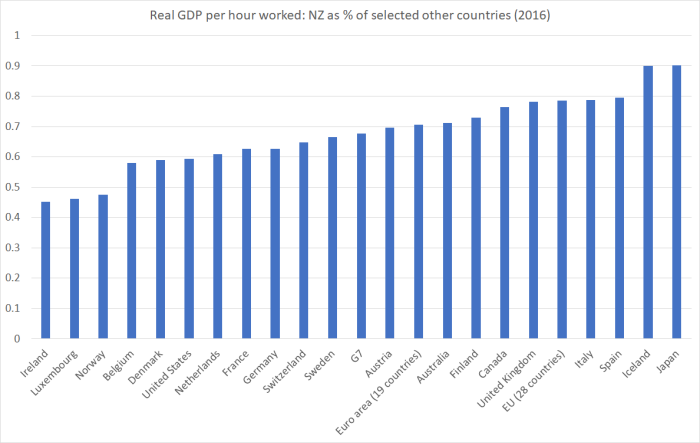

My favourite base for comparison is real GDP per hour worked. Levels comparisons are really only approximate, but using OECD data – based on the 2010 purchasing power parity (PPP) exchange rates – here is how New Zealand’s real GDP per hour worked compared to the OECD countries that have higher average productivity than we do. You could discount Ireland to some extent – there are some measurement/classification issues around their tax system, and in truth productivity in Ireland might be nearer German or Dutch levels. On the other hand, I don’t show Slovakia which, on this particular metric, went past us a couple of years ago.

As it happens, of the 23 bars shown, the G7 countries’ total is the median observation. Our real GDP per hour worked in 2016 was only 67.6 per cent of that for the G7 group of countries as a whole. In other words, it would take a 50 per cent increase from here – with no change in those countries – for us to catch up again. If we take the subset of countries from Belgium to Germany, it would take about a two-thirds increase in our average productivity to catch up again. When the OECD data series starts – 1970 – average productivity here was about equal to that of the G7 countries as a whole.

Another way of looking at these same data is to look at when other countries reached the level of productivity New Zealand had in 2016 (37.5 USD per hour, expressed in real 2010 terms, converted at PPP exchange rates).

Some of the other OECD countries first get to that level in the early-mid 70s (Luxembourg, Switzerland, Netherlands, Norway). Two only got to our current level in the mid 2000s (Iceland and Japan), but of course even that leaves us at least a decade behind. The G7 countries as a group got to our current level of real GDP per hour worked in 1990, and the median country (as per the chart above) got to our current level of real GDP per hour worked in 1989 – 27 years, or just over a quarter of a century, ahead of us. Jacinda Ardern would have been in primary school then.

One can’t too much weight on the precise numbers/data – different conversion rates will produce somewhat different gaps – but the gaps are huge, and we – in aggregate – are a long way behind. I’m hoping – but am not optimistic – that today’s conference might help shed some further light on the matter. I’d settle for some hardheaded realism about how far behind we now are – lagging the core of the advanced world (the countries we usually liked to compare ourselves too) by a quarter of a century now.

And, of course, the idle hope is that some political leaders might (a) care and (b) set about doing something about closing the gap. Productivity is the foundation for prosperity, and many desirable social goals. It isn’t everything of course – even if, in economic terms, it is almost everything in the long run. But in all the hoopla about the first 100 days of the government, or even its challenges for the next thousand, there wasn’t any sign of a determination to reverse these decades of underperformance. Sadly, although there were a few references to the productivity failure during the campaign, the new government seems to have lost interest even faster than their predecessors did.

That’s a worry – your first paragraph implies that the Productivity Commission (plus various government departments) spent time and money organising a conference, inviting a senior OECD official to speak to the confreres. The paragraph concludes that much of the discussion had the feel of addressing a wider audience of the OECD on topics that were not “true to title”

who organised it? Was the conference trojan horsed?

Dislike saying this again – I have said it before – this seems to be a repeat of the Wellington Bubblewrap Biosphere condition of insularity where nothing gets in from outside. BubbleWrap is a registered trademark of Sealed Air Corpn

(a) Have a look at the website for the https://productivity.govt.nz/ – there is nothing about the conference. There are no papers published. There are no updates for 2018. It is out of date. I have a long standing interest in technology. Will the presentation papers on technology be published and listed at the commissions web-site

(b) The news over the past couple of days has dwelt on the congestion implications in Auckland the supposed engine-room of the NZ economy. Yet 700 new motor vehicles are being added to Auckland roads each week and inbound migration keeps running at 120,000 per annum most of which floods into Auckland. The place is de-productivising itself

(c) and we are providing a platform for an OECD official to come here and lecture the Northern Hemisphere

LikeLike

Phil Goff intends to charge a congestion toll into Auckland and a Hotel Levy. Perhaps he should also charge a inbound and outbound Airport levy on passengers. All of which adds to GDP and helps pay for Len Browns intercity rail currently with a cost blowout from $2 billion to $4 billion. to get from Britomart to Mt Eden.

LikeLike

Probably a bit unfair. The Productivity Commission is mostly doing stuff that adds some value, and employs some able people. The interagency Productivity Hub – which organised today’s conference – does have an update newsletter people can sign up for https://www.productivity.govt.nz/get-involved.

UPDATE 20/2 The PC has now posted links to presentations/slides etc

https://www.productivity.govt.nz/news/2018-productivity-hub-conference-on-technological-change-and-productivity

LikeLike

I suspect that politicians will continue to shy away from the necessary changes until the public wakes up and realises that essential services can’t be paid for. The public will only then accept changes in the face of a funding crisis.

Regrettably, NZ can’t be kicked out of the OECD for poor performance. That might have beeen the signal for change being necessary.

What changes are required is unknown to me, but I’m confident that if they were politically-easy changes, some government would have made them since 1996.

Unfortunately, the world will lend NZ enough money for long enough that the crisis will be long delayed and NZ will go through the decades’ long slow decline the public appears to accept, and even welcome at times because it means their weekends remain sacrosanct.

Demographics plays a large part in this. The old age population doesn’t gain from reforms as immediately as the working age population.

LikeLike

With GDP annual growth hovering around 3.5% and likely the highest GDP growth in the OECD, I think it is hardly a bad scorecard to be tossed out of the OECD. Essential services are being paid for because tourists and international students fork out $15 billion every 12 months into the local communities. There is a 100% conversion rate from the pockets and credit cards of these visitors into the pockets of local retailers, restaurants, entertainment centres, pubs, etc

The world continues to lend NZ money because NZ net wealth is $1.4 trillion against household debt of $203 billion.

LikeLike

I expect Micheal agrees with that statement completely,

“They are all real world considerations that reform advocates need to grapple with – it isn’t enough to simply assert (correctly) that a government with its own currency can never run out of money.” – Michael Reddell

https://croakingcassandra.com/2017/07/31/a-radical-alternative-to-macro-policy/

Commercial banks have a similar property to the government when it comes to their own bank deposits (which make up a substantial part of the money supply).

If your arguing some exchange rate behavior, then say that not some institutionally impossible fantasy.

LikeLike

Governments need never run out of money when they have their own currency (although they still sometimes choose to default). It also isn’t much of an issue in NZ where govts have responsibly opted for low and fairly stable debt (unlike, say, the increasingly worrying US fiscal position).

The original comment in this chain seems to have been around overseas borrowing by NZ residents as a whole. There, equally obviously, defaults can happen. However, the net external indebtedness of NZers as a % of GDp has been stable (but high) for 25 years now. The high level of indebtedness is mostly a reflection of our rapid population growth rate (on average) in a country with a modest savings rate.

LikeLike

Oops, wrong reply button for the above comment.

LikeLike

“I suspect that politicians will continue to shy away from the necessary changes until the public wakes up and realises that essential services can’t be paid for. The public will only then accept changes in the face of a funding crisis.”

The country is and will remain more than capable of funding itself indefinitely. The notion that NZ can run out of money is pure ideological drivel, basically all the money which is spent in and around the NZ economy originated in a financial institution in NZ and probably still resides here.

One part of this issue is NZ needs to do more publicly funded research and development as private sector research can not afford to take the same research risks (which may not pay off soon, but may be incredibly valuable longer term). The repetitive demands, and political goals, to shrink public sector spending as a proportion of GDP do not help us to face up to this.

LikeLike

Excluding the $5 billion in dividends plus also the extra undisclosed billions in royalties for the use of the brand and other shared services costs every year that our monopoly Australian banks transfer to their parent company in Australia.

LikeLike

Even so, do Australian banks extract transfer payments in $AU or $NZ? In $AU they must have of course have traversed through a Forex market somewhere in between.

LikeLike

It all depends on whether internationally there is confidence in the NZD. Theoretically if we closed off our economy and become just kiwi manufactured and consumed then as a closed system which does not import any overseas production then what you say is true, that NZ can fund itself indefinitely.

But unfortunately we do not manufacture these days but import most of what we need which means that a overseas seller must have confidence in the NZD as a stable medium of exchange. We can only buy better and more if we have a higher NZD. If confidence in the NZD falls then of course we have to pay more for our imports. But a loss of confidence means that you can issue all the NZD you like but the overseas suppliers would not sell you their products if the NZD value falls dramatically and consistently.

LikeLike

That’s exactly right. The original comment is extremely miss-leading because it implied some kind of financial default was a possible outcome, its not. In fact what is being argued is that there will be some impact on the exchange rate.

Of course in practice it is considered that NZ dollar could be lower and more helpful to our exporters.

LikeLike

Does our host – an economist – not have something to say about this statement? Because it’s extraordinarily ignorant, Social Credit stuff. Were it true we would have no need to borrow overseas now or at any time in the last century or more. Even politicians of the past like Vogel, filled with ambitious ideas for development, did not believe such nonsense, nor the likes of Alexander Hamilton in the early American Republic. They knew they had to borrow on international markets.

That’s not actually what getgreatstuff said. In the context of a discussion about productivity he made the very sound point (as the blog host is doing), that lagging productivity over long periods of time, will eventually produce a situation where we’re not generating enough money per person to pay for the services we consume – largely because more productive countries are slowly and steadily outbidding us for products (like drugs) and services (like doctors, nurses and teachers). In fact we’re already well on the way there; how many American or German doctors and nurses do you see in our hospitals compared to those we’ve hired from the Developing World. Them we can still outbid.

And the phrase “run out of money” is itself the sort of nonsense spouted by people who walk around saying that nations are not like companies (true) and can’t go broke (false). Look at Iceland. Look at Greece; technically they never ran out of money either – but there’s also no doubt that they went broke. Try telling your average Icelander or Greek who couldn’t get cash out of the ATM’s that his country was not broke, and that each was “more than capable of funding itself indefinitely.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I expect Micheal agrees with that statement completely,

“They are all real world considerations that reform advocates need to grapple with – it isn’t enough to simply assert (correctly) that a government with its own currency can never run out of money.” – Michael Reddell

https://croakingcassandra.com/2017/07/31/a-radical-alternative-to-macro-policy/

Commercial banks have a similar property to the government when it comes to their own bank deposits (which make up a substantial part of the money supply).

If your arguing some exchange rate behavior, then say that not some institutionally impossible fantasy.

LikeLike

The government’s capacity to play a lead role in driving innovation and productivity was destroyed by the demise of the DSIR. Now we have an “Innovation Institute” that spends a good part of its budget on entertaining itself or its corporate welfare clients. Unfortunately there seems to be little interest in making the necessary changes. New Zealand’s scientific institutes forty years ago made a huge contribution to our economy, one only has to think of the work of the Grasslands’ scientists. Science is no longer seen as an attractive vocation; better to be a lawyer or get an MBA.

LikeLiked by 3 people

This is exactly where the problem is. Government has removed itself from the role of incubation of high productive industries. The tourism industry gets a budget of $130 million to sell NZ to tourists. With 4 million tourists arriving every 12 months together with 125k international students guess where all the new jobs are in? Rocket engineers?

LikeLike

It’s one thing to describe the productivity problem, it is another thing to describe why we have low productivity and lastly a solution to our problems. I think we are still stuck in the first stage.

LikeLike

I’ve done both in other posts, and will come back to those issues in discussing today’s conference.

But it is at least as important that leaders first recognise/accept there is a major problem.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That of itself is part of the problem, especially as I suspect many of them do not understand the issue

LikeLike

Our largest industries are in the service sector. The problem is very clear. The best service is in having more people. Until you can automate chefs, waiters, cleaners, baggage handlers, productivity will remain low.

This is a Labour led government. The recognition of productivity as an issue equates to more automation and more people out of jobs or more people back in school to retrain funded by the government and more money in the hands of the few shareholders that own these automated entities. The masses just have to contend with being out of work. Not exactly the leading objective of a Labour led government??

LikeLike

Not sure I agree, history would suggest that as one sector dies another is borne. However, I venture to suggest that NZ has some signicant societal issues with success and achievement in business.

LikeLike

Exactly, as our manufacturing and productive industries get replaced by the new larger and larger service sector. Sounds like we are in agreement?

LikeLike

Given that robots have just learned how to open a door there is still a long way off to replace humans in the service sector. My mother is currently being cared for by caregivers 4 times a day in her own home as she elected not to be placed in a rest home. She has a dedicated human lift system powered by a battery provided by our healthcare but needs to be operated by a human. Health and safety rules still requires 2 caregivers to be present at all 4 care times. Therefore even with an automated human lift system, 2 humans are still required to operate prior to a lift. An hour each session times 2 people times 4 times makes it a full 8 hour working day.

It therefore requires the equivalent one young person to look after an immobile old person. It is clear that as our population ages, we will need the equivalent number of younger people to care for them.

LikeLike

Real GDP per hour worked is the gospel. Preach it.

I say that even as I’m not a fan of GDP in general.

LikeLike

I do not know of too many workers happy with less hours at work as it translates to less pay but having to produce more.

LikeLike

Fletcher Building is finding out that making its asset resources work harder with higher Revenue does not necessarily translate to a bottom line profit. Its value decimating rapidly from a high of $11.00 to now around $7.70 a share with billions wiped from its capital value in announcing a huge $160 million losses to be confirmed. Chalk that to Maori Iwi groups, NIMBY and Heritage NZ groupies blocking and delaying development.

The Labour Government wants to tell us it is more capable than Fletcher Building in building houses and will not run up risk losses on behalf of the taxpayer??

LikeLike

This is a lesson that productivity without profitability is a bigger problem.

LikeLike

Chalk that down to lack or proper risk management by Fletchers.

LikeLike

Not necessarily. There is a tendency for imported senior managers from overseas, used to larger markets to try and adopt high volume and low margin practices. The small size of NZ markets mean that a low volume and high margin approach is more successful. But many large NZ companies want to get bigger and bring in expertise from offshore with the preconceived notion that large market strategies can create a larger company. The reality is you can’t grow a large company in NZ any larger when the market is so small.

LikeLike