A couple of years ago I did a post on some remote and very small places, many of which had quite a lot of land and very few people. My point was to suggest that New Zealand was quite unusual in having so many people in such a remote spot, all the more so when much of the population growth had been accounted for by deliberate immigration policy. As readers will know – apart from anything else, I keep pointing it out – over at least the last 70 years, productivity growth here has been pretty poor and we’ve drifted a long way down the global league tables. My proposition is that the two stylised facts aren’t unrelated.

At the time of the earlier post, my young daughter was fascinated by a book on remote islands. At the moment – a bit older now – she’s got really interested in Wales and keeps telling me all sort of interesting snippets. But talking with her about Wales reminded me that at the time of the Lions Tour last year I’d been meaning to write a post highlighting just how little population growth there had been in some of the outer reaches of the United Kingdom.

More generally, I’d been thinking about how global studies attempting to assess the economic impact of immigration focus on comparing across countries. In some ways, that makes sense – data are often easier to come by, and countries control immigration policies. But I suspect there is information in the experiences of remote regions. After all, if there were typically really good economic opportunities in remote regions, people in a country are free to move there. The population of the United States, for example, has risen by over 200 million people in the last 100 years – through a mix of immigration and (mostly) natural increase. Those peope have been free to locate themselves where the best opportunities are. One can think of parts of Canada or Australia in the same way. And if our politicians had made different choices in the 1890s, we could simply have been part of the Australian Commonwealth, and it seems unlikely that the economic opportunities here would have been much different if that choice had been made.

Here I’ve focused on the last 100 years or so. Why? Mostly because just prior to World War One New Zealand had probably the highest (or 2nd or 3rd highest) GDP per capita of any country in the world (per the historical tables put together by Angus Maddison). But it was also some decades on from the first big waves of colonial settlement (whether here, Australia, Canada, or the mid-west and west of the United States). At around 1 million people in the 1911 Census, New Zealand was already a functioning country of reasonable size (not large, but there are many smaller countries even today).

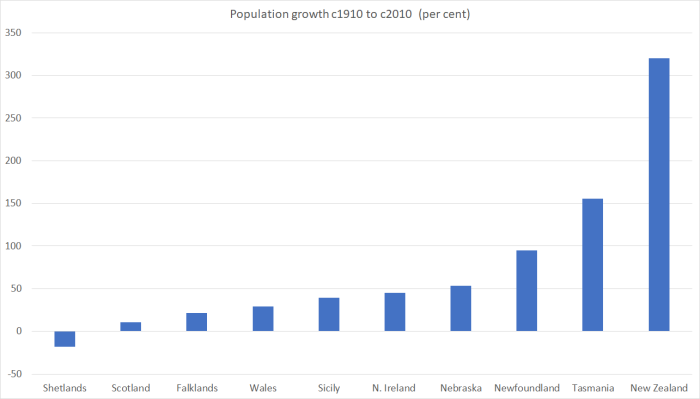

In this table I’ve focused on population growth between the Census nearest 1910 and the most recent Census (in most cases 2010 or 2011, but in New Zealand 2013). The chart shows the percentage increase in population for these remote regions of countries, plus that for New Zealand (Nebraska gets chosen as a “remote” US area mostly because I happen to have been there a few times.)

Australia and Canada (and the US) have had rapid national population growth rates, but these remote regions (Nebraska, Newfoundland, and Tasmania) have had much lower population growth rates than New Zealand. (And, on checking, each of those three have lower population densities now than New Zealand does.) But given that all of these regions have small populations, relative to the respective nation’s total population, there would have been nothing to stop lots of people gravitating to the remote spots if there was real evidence of good economic opportunities for many people in those places.

It has, after all, happened in some remote regions: West Australia for example, now has about 10 times the population it had in 1910, presumably attracted by the mineral resources that mean West Australia has the highest GDP per capita of the Australian states. And two really remote parts of the United States – which I didn’t show on the chart, partly because they were settled so much later (not admitted as US states until 1959) – are Hawaii and Alaska. Both have had faster population growth than New Zealand over the last 100 years (although between them only around 2 million people in total): in Alaska’s case no doubt the oil resources attracted people (Alaska also has among the highest GDP per capita of any state).

But over that hundred years – or any shorter period you like to name really – New Zealand (like Wales, Northern Ireland, Tasmania, Nebraska, or Newfoundland) has had no big natural resource discoveries, or asymmetric productivity shocks specifically favouring our location. Like those places, we’ve only had the skills of our people and the instititutions we’ve built or inherited (in the case of this group a fairly-common Anglo set) to make the most of, and to overcome what appear to be the resurgent disadvantages and costs of distance/remoteness. Our birth rates won’t have been much different over long periods, and New Zealand like all these places – the Shetlands most extremely of the places on my chart – have seen outflows of our own people. The big difference here is immigration policy, which has actively sought to substantially boost the population.

Try a thought experiment. Say the New Zealand and Australian governments had simply combined their respective immigration policies over the last 100 years or so (eg if New Zealand was offering 45000 residence approvals per annum and Australia 200000 – similar to the current policies – the two countries simply said we’ll issue 245000 residence visas and the arrivals can go wherever they like), what would have happened. By construction, the total population of the two countries would have been pretty much the same as what we actually see (5.4 million in 1910, and about 29 million now) but what would the distribution look like? We know that in Australia – given the same choice – the remote region with a mild climate and no big new natural resources (Tasmania) saw much weaker population growth than the rest of Australia. Why wouldn’t it be the case that New Zealand would have experienced much the same phenomenon? At Tasmania’s population growth rate for the last 100 years we might now have a population of around 2.5 million. After all, for almost 50 years now native New Zealanders have (net) been relocating to (the non-Tasmania) bits of Australia, so why – given the free choice – wouldn’t the migrants – facing a free choice at the point of approval – have done so too?

Would we have been better off? The migrants who went to Australia instead presumably would have been – both judged from revealed preference (they made the choice) and that incomes in Australia are higher than those here. I’d argue that the smaller number of New Zealanders probably would have been economically better off as well. Natural resources are still a huge part of the economic opportunities in these remote islands – perhaps still 85 per cent of our exports – and those limited resources would be spread across a considerably smaller number of people. For those who simply prefer “more people” for its own sake, perhaps they’d have been worse off – but then such people could have self-selected for Sydney or Melbourne (as Tasmanians of a similar ilk do, or people in Newfoundland who wanted to be part of something big self-select for Toronto).

I’m not suggesting something conclusive here, just that people pause for thought, and reflect on what questions the experiences. For a remote place we aren’t particularly lightly settled, and especially not as a remote place without the sort of abundant natural resources of – say – a West Australia. We’ve had no distinctive favourable productivity shocks, and we’ve long lost any claim to be the richest (per capita) country on earth. It is no surprise that some people want to move here – plenty would want to move to Nebraska if it had its own immigration policy like ours – but there isn’t much evidence, from experience of other remote regions, to suggest we benefit from them doing so. Without big new natural resource discoveries, remote places – regions, territories – in the advanced world tend to have quite weak population growth rates. It isn’t obvious why in New Zealand we should let immigration policy up-end that otherwise natural outcome.

In Europe Finland could be considered a remote region. It has only a small land border with other EU countries -the top of Sweden and Norway. It does have a long border with Russia -but that brings challenges as well as opportunities -many on both sides do not forget Russia was once Finland’s colonial master (as was Sweden before Russia) and the Soviet Union tried to reclaim its territory in WW2.

Finland has not utilised mass immigration to improve economic growth (although Finns are free to move to more central parts of Europe -and all EU citizens can move to Finland). Finland hasn’t relied on its stock of natural resources -which hasn’t changed -no oil boom for Finland -unlike Norway. Finland’s stock of natural resources is rather limited, especially considering its challenging climate.

100 years ago -post independence Finland massively concentrated on education to improve its human resources. That was seen as the way forward -both individually and collectively. This has been a success, which isn’t surprising because places with the best institutions, which gives the most opportunities for individuals to reach their full potential are successful. Lots of research about institutions indicate this.

Places with a high amount of natural resources but poor institutions do badly. As the 100 year capitalist experiment in the US’s Appalachia shows.

https://qz.com/1167671/the-100-year-capitalist-experiment-that-keeps-appalachia-poor-sick-and-stuck-on-coal/

Perhaps a 100 years ago the reason NZ was wealthy was a combination exploitable natural resources (refrigeration opened up the global market for diary and lamb) and good institutions that spread opportunity across society. The Liberal govt of 1890 to 1912 being led by several ministers who were very cognisant of the need to avoid the problems of other agricultural exporters -in particular the Highland Clearances and the Potato Famine -Ireland continued to be a net food exporter through the whole potato famine period.

Michael NZ can’t do much about its stock of natural resources (other than dilute it on a per capita basis as you argue) but we can improve on our institutions and thereby improve our human resources. Perhaps if NZ did this better we wouldn’t need a mass immigration programme to counteract the mass emigration of New Zealanders away from NZ?

LikeLiked by 2 people

It is said NZ does produce skilled workers. OK many then leave.

Probably further expansion of tertiary education for New Zealanders wouldn’t help our nation economically and anecdotally I suspect less classroom time and more practical would be better use of our taxes. What I suspect would work is to improve the quality not quantity. If you are really wish to be the top of your chosen field then you look for the best worldwide. For rugby players or rowers you stay in NZ. We need the same option for academics; that would require stellar salaries and for scientists long term serious investment in research. That way we may produce and retain an intellectual elite.

LikeLike

Interesting idea, although closeness to other academics tends to be a big issue for academics (eg ease of travel for conferences, joint work etc). Email etc changes things to some extent, but there isn’t much sign anywhere of top-notch universities developing in remote locations – some of the Scottish universities and Trinity College have some pre-existing establishment advantages, but even they are not top-notch in many fields.

LikeLike

Maybe Bob. In Finland being a teacher is considered a high status occupation (I think pay is comfortable not amazing). I have a Finnish friend who applied to get into the Finnish nursing teaching course. She had to sit an exam (which is common for all sorts of courses in Finland), which over a 100 nurses sat, while the space on the course was only open to a couple of students!

Maybe if we could make NZ a less easy place to leave this would help? Another Finnish friend lived for a while in Sweden. Even though he was a fluent Swedish speaker he never felt truly comfortable, eventually returning to Finland.

Maybe if NZ had a stronger culture -developed a fusion food culture for instance, more affordable housing (my big issue) and stronger communities etc, less people might leave and we could worry less about the immigration to replace emigration.

Maybe if NZ got these sort of institutional factors right then gradually productive businesses and enterprises would grow -in both natural and human resource based industries…..

LikeLike

Spent a lot of time over the last 2 days waiting and watching for the launch of Rocket Labs latest rocket streamed Live. I was amazed that many Kiwis thought it was an overseas company launching in NZ and more worried about the birds and the insect population than the fantastic technological achievement that New Zealanders can muster against world wide competition.

I am also very surprised the lack of mention in your own blog on this potential technological advancement and the impact to productivity other than the usual rhetoric on distance and remoteness and immigration being the cause when we all know it is more to do with technology and innovation being widely applied.

Samsung trades $350 billion in sales with 250k staff. It is a heavily Korean government subsidised private company. This is how to get productivity. It is in high tech and it is in manufacturing.

LikeLike

i spent a whole post on Rocket Lab last year, including noting the two factors that seem to have explained how it has done well so far: public money, and our extreme physical remoteness (not many planes or ships around the east coast of the North Island – unlike, say, Florida). As I’m pretty sure i said then, good luck to ROcket Lab if they can survive/flourish on their own merits, but precisely because of the reliance on extreme remoteness – for a launch pad – it is unlikely to foreshadow the rise of lots of other new industries in NZ.

LikeLike

THanks Brendon

Not only Finland, but Iceland even more so count as remote. I didn’t include them here precisely because they were whole countries, and had control of their own immigration policy (so we don’t just see voluntary choices within countries). Of the two, Iceland has had almost as rapid population growth as NZ – presumably almost all natural increase – but Finland has had much slower population growth. Ireland could also be treated as “remote” and interestingly it had similar population growth to Northern Ireland – but they have found a key policy – corporate tax – to enable them to lift incomes above those in other British Isles remote regions (Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland). but even then for a population that peaked in the 1840s…….

I agree we could/should improve things like education and related human capital and institutional things. But it would be a great deal easier to cut immigration, which in itself might deter some NZ from leaving, and try to do the institution building stuff as well. Iceland also does very well on the latter.

We can offer v good material living standards here, but it is a real self-imposed uphill battle to do it for many with such a large-scale (not very skilled) immigration/population policy.

LikeLiked by 2 people

First you need to focus on the industries and the jobs. At the moment successive government has focused on education. Educating high skilled jobs for a non existent high skilled job market equates to more high skilled kiwis leaving for offshore high skilled jobs. I would have thought that by now our educators would have understood that you can’t have the cart ahead of the horse and expect the cart to move fast.

LikeLike

“First you need to focus on the industries and the jobs. ”

No, first you cut off the rapid influx of low skill immigration. This is something that can achieved (virtually) overnight with a mere policy change. Institutional changes take time.

LikeLike

The worm may turn. The pro growth arguments fly in the face of common sense. Nichola Sturgeon is claiming Scotland needs migrants for economic growth, however Migration Watch UK last year noted that “immigration as a solution to a pensions problem has been dismissed by all serious studies”, pointing out among other factors that “immigrants too will grow old and draw pensions”.

http://www.breitbart.com/london/2018/01/16/scotland-mass-migration-challenge/

It’s amazing that informed people (Noelle McCarthy, Jim Bolger, Paul Spoonley) haven’t been confronted with an alternative set of facts.

Jordan Peterson ran rings around a Channel 4 journalist. He burst a bubble but the bubble was the making of the establishment.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Nichola Sturgeon should do some cross-country research ….

Meanwhile closer to home – NZ has discovered how to breed baby-boomers – otherwise known as the current wave of nascent age-pensioners plus all new age-pensioners since 2010

1966 census there were – 1,098,473 age 20 and under – that’s all the normally resident baby-boomers some of whom would have been imports – no idea how many would have been naturals – at least they all would have contributed to the crown purse by 2010 and not all of them would make it to 2010

http://www3.stats.govt.nz/New_Zealand_Official_Yearbooks/1966/NZOYB_1966.html#idchapter_1_8140

Baby Boomers – Data extracted from censuses 1996-2013

Baby-Boomers Born 1945-1965

NZ-Total number of Baby-Boomers – all groups

1996 1,111,000

2001 1,110,000

2006 1,134,000

2013 1,138,000

Can’t make any more of them organically

Asian – Boomers – Total

1996 66,000

2001 80,000

2006 97,000

2013 113,000

Between 1996-2013

The National total of Baby-Boomers grew 27,000

The Asian total of Baby-Boomers grew by 47,000 (Que?)

Which means 20,000 of the original 1996 national crop never made it

LikeLiked by 1 person

Malthus had a theory of a finite world, where the world would become overloaded with people without the means of supporting them. Michael has a similar view to immigration in NZ. There is a finite productive capacity and more people just dilutes the wealth.

That is a really pessimistic view and the corollary is that shrinking NZ’s population is desirable for per capita wealth.

This hasn’t been in the experience of Australia, Canada, Singapore and the US.

By many measures NZ is longer isolated as it once was, be it trade-flows, population flows, international travel and exposure to international thought. I wonder if Michael is using reason to justify his instincts.

Positivity and problems solving is a more productive attitude to nihilism.

The conventional wisdom of fifty years ago was that Singapore will remain a poor backwater, that East Asia, in general, will remain poor due to being resource-poor, uneducated, overpopulated and the distance from rich markets.

Let’s us not have excuses why we can’t do things. But ask, what is holding us back.

LikeLike

Malthus might be wrong about the timing but not the over all trend. If global warming affects food supply he is dead right.

LikeLike

Hi Mike

A few quick thoughts –

I intuitively agree with your basic proposition that NZ would be better off (from an economic perspective) if it’s relatively limited natural resources were spread across a smaller population.

I also agree that, given a choice, immigrants on average seem to prefer less remote places.

However I’m not sure it follows that low population of growth in the places in your chart above establishes that NZ’s “otherwise natural outcome” is also a relatively low population.

Immigrants’ preference for less remote places is a function of the choices available to them (across countries accepting them and then within the country to which they have been given admission).

If each of the remote places in your chart were a country able to set its own immigration numbers, no doubt many immigrants would chose to go there (as the best of their available options).

In short, the hierarchy of immigrants’ preferences may be “natural”, but obviously there is nothing “natural” about the range of places available to immigrants.

Cheers

Tony

LikeLike