After my post last week, prompted by the Reserve Bank’s recent statement that

Work is currently under-way to assess the future demand for New Zealand fiat currency and to consider whether it would be feasible for the Reserve Bank to replace the physical currency that currently circulates with a digital alternative.

I exchanged notes with a few readers with some in-depth thoughts on the issue, and found my way to some other relevant material including the recent first report of the Swedish central bank’s e-krona project. And I noticed that Phil Lowe, Governor of the Reserve Bank of Australia, was giving a speech on exactly that topic – “An eAUD?” – yesterday. I gather that among advanced country central banks this is now treated as quite a high priority issue. But it is also interesting that – contrary to the Reserve Bank of New Zealand comment about their work – both the RBA and the Riksbank are only talking about the possibility of electronic retail cash as a a complement to physical currency, rather than a replacement for it (and Sweden already has one of the very lowest currency to GDP ratios of any country anywhere).

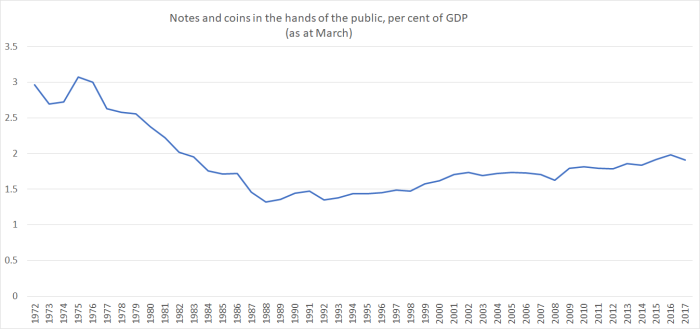

Lowe’s speech was interesting, but also unsatisfying and unconvincing in a number of important areas. As a New Zealand reader – from a country with many of the same banks (and presumably banking technology options) – I was struck by the contrast in what has been happening to currency to GDP ratios in the two countries. Lowe illustrates that the share of transactions being effected by cash is also dropping sharply in Australia. But here is the New Zealand currency to GDP chart I ran last week

And here is comparable Australian chart from Lowe’s speech.

45 years ago, the levels of the two series were very similar. Since then, the trends have been very different and now there are many more physical AUDs in circulation (relative to GDP) than NZDs. But there is nothing in Lowe’s speech about just why so much physical currency continues to be held in Australia – far more than any plausible transactions demands (supported by evidence from payments practices data) would support. Ken Rogoff suggested, in a US context, that the bulk must be held to facilitate illegal activities, or tax evasion in respect of otherwise legal activities. Perhaps Lowe felt it wasn’t his place to venture far into territory around lost tax revenue, crime etc, but it was still a surprise to see no mention at all, when the RBA seems largely content with currency physical currency arrangements.

I was also rather surprised to see no serious engagement with the issues around the near-zero lower bound on nominal interest rates, which arises because of the option to convert unlimited amounts of bank deposits etc into zero-interest physical currency, an option that would be likely to be exercised on a large scale if official interest rates were dropped much below, say, -0.75 per cent. Like New Zealand, Australia hasn’t yet approached the near-zero bound. Neither had the US, Japan, Switzerland, Sweden, or the euro-area, until they did. But Australia’s official interest rate is now only 1.5 per cent. Perhaps it will be raised a bit before the next serious recession hits, but no prudent central banker could be discounting the possibility that even the RBA will hit the effective floor – and limits of conventional monetary policy – when that next recession comes. Dealing effectively with that floor – by significantly winding back access to physical cash – should be one important consideration when central banks are considering e-cash options. But Lowe doesn’t even mention the issue, and while the limits of monetary policy might not have been of much interest to his immediate listeners (the Australian Payment Summit), interest in his speech – and the issue – goes much wider than the immediate audience. (Strangely, in the Riksbank’s work they also talk in terms of zero-interest e-cash options – albeit with the flexibility to change that at a later date – and thus don’t really grapple either with the near-zero bound problem.)

To me, the heart of Lowe’s speech was his discussion of the possibility of the Reserve Bank of Australia issuing one or other of two types of eAUDs.

-

An electronic form of banknotes could coexist with the electronic payment systems operated by the banks, although the case for this new form of money is not yet established. If an electronic form of Australian dollar banknotes was to become a commonly used payment method, it would probably best be issued by the RBA and distributed by financial institutions, just as physical banknotes are today.

-

Another possibility that is sometimes suggested for encouraging the shift to electronic payments would be for the RBA to offer every Australian an exchange settlement account with easy, low-cost payments functionality. To be clear, we see no case for doing this.

I’m not sure I have a particularly good sense of what the first option involves, but here is how Lowe describes the possibility

The technologies for doing this on an economy-wide scale are still developing. It is possible that it could be achieved through a distributed ledger, although there are other possibilities as well. The issuing authority could issue electronic currency in the form of files or ‘tokens’. These tokens could be stored in digital wallets, provided by financial institutions and others. These tokens could then be used for payments in a similar way that physical banknotes are used today.

But he doesn’t seem keen, and so I’m going to focus my discussion in the rest of this post on the second of his options. The issues and risks are pretty similar for both options, and I favour (provisionally) something like the second option.

At present, central banks offer exchange settlement accounts to facilitate the interbank settlement of transactions (the RBNZ policy is here – something they must be reviewing, as there was an RFP for work in this area a few months ago). These accounts facilitate payments, but they also allow entities given access to such accounts to hold electronic claims on the Reserve Bank (that are free of credit risk). Central bank physical banknotes are also credit risk-free claims on the central bank. But one set of claims is newer technology, regularly updated, enabling banks to both easily make payments and store value, while the other is a declining technology.

Here is how Lowe describes the option in this area

Another possible change that some have suggested would encourage the shift to electronic payments would be for the central bank to issue every person a bank account – for each Australian to have their own exchange settlement account with the RBA. In addition to serving as deposit accounts, these accounts could be used for low-cost electronic payments, in a similar way that third-party payment providers currently use accounts at the RBA to make payments between themselves. Some advocates of this model also suggest that the central bank could pay interest on these accounts or even charge interest if the policy rate was negative.

I’m not sure anyone argues for this approach to “encourage the shift to electronic payments”, but rather to reflect the world we now find ourselves in, in which electronic payments media and (records of) stores of value overwhelmingly dominate. If favoured banks and financial institutions are allowed access to risk-free overnigh electronic balances, why shouldn’t ordinary Australians (or New Zealanders) have such access? After all, at the absurd extreme, central banks could still insist that to the extent banks wanted to deal with them, they did so in physical banknotes. It would be wildly inefficient to do so, but it could be done. But if it doesn’t make sense to restrict such “big end of town” transactions to physical currency, why does it make sense to restrict ordinary citizens’ access to central bank outside money?

But the RBA is firmly opposed to change of this sort.

On this issue, we have reached a conclusion, rather than just develop a hypothesis. The conclusion is that we do not see it as in the public interest to go down this route.

Why? Lowe raises three concerns, of which two are substantive and one is mostly rhetorical.

If we did go down this route, the RBA would find itself in direct competition with the private banking sector, both in terms of deposits and payment services. In doing so, the nature of commercial banking as we know it today would be reshaped. The RBA could find itself not just as the nation’s central bank, but as a type of large commercial bank as well.

In times of stress, it is highly likely that people might want to run from what funds they still hold in commercial bank accounts to their account at the RBA. This would make the remaining private banking system prone to runs.

On both counts, I think he is largely wrong, and that any issues are quite readily manageable.

It isn’t at all clear why (many of) the public would want to use an RBA (or RBNZ) exchange settlement account for routine transactions services. Revealed preference suggests that people are mostly very happy to run the modest credit risk associated with using private bank deposit and payment services. Almost all of us now use bank deposits for most of our transactions – even when physical cash is a perfectly feasible alternative (eg there is no additional cost in time or anything else to, say, taking out $400 from an ATM once a week rather than say $200). And in the handful of places where private banknotes still circulate (eg Scotland) there doesn’t seem to be any unease about taking them, or transacting with them.

In addition, banks can offer bundled products – cheaper fees for example where you have your mortgage, or term deposits, with the same bank as your transaction account. No one proposes that central banks will be offering mortgages, term deposits or any of the rest of the gamut of products the typical commercial bank makes available.

I’m not aware that anyone is suggesting central banks should set out to out-compete banks. The argument for making central bank e-cash readily available is about a fallback – a residual option, much as cash is now for many purposes. Central banks almost inevitably would lag behind commercial banks in their technology anyway, which wouldn’t make a central bank transactions account product particularly attractive. And it could easily be kept that way – don’t offer provision for regular direct debits etc, don’t allow overdrafts at all, keep the fees just a bit higher than those on commercial bank accounts, and – of course – be prepared to adjust the interest rates paid (or charged) on credit balances to limit potential demand. What would be on offer would be a basic credit-risk free product – something similar to the fairly basic products central banks provide to banks themselves. Frankly, I’d be a bit surprised if there was much (normal times) demand at all (and I think back to the days – decades ago – when the Reserve Bank offered – in direct competition with the private banks – cheque accounts to its own staff; perhaps some people used theirs extensively, but I used it hardly at all).

Lowe’s other concern – and I’ve seen this concern in other places too – is that provision of e-cash for ordinary citizens might destabilise the banking system. As he noted earlier in his speech “it is likely that the process of switching from commercial bank deposits to digital banknotes would be easier than switching to physical banknotes. In other words, it might be easier to run on the banking system.”

Frankly, if the only thing that prevents runs on the banking system is that it is too hard to run to cash, central banks and regulators have bigger problems that they might need to address directly. Runs are often quite rational – there are real issues with the “victims” funding and/or asset quality. If it really were easier to run with electronic central bank cash, banks – and their regulators – might need to look to the size of the capital and liquidity buffers. As it is, Lowe seems to be suggesting banks can free-ride on technical obstacles their (retail) depositors face.

But I’m not really persuaded that simply making available a basic retail e-central bank cash option would either increase the prevalence of runs or threaten the stability of the financial system. When there is a concern about an individual bank (or non-bank) people “run” electronically anyway – mostly they don’t withdraw their deposits into physical cash, but into liabilities of another private institution (and we seem to have been seeing such a quiet run on UDC in recent months). Wholesale runs – the sort that took down Bear Stearns and Lehmans – all happen electronically. Banks themselves can run straight to central bank cash, when they cut lines on each other. Is the Governor really suggesting that it is just fine that wholesale investors should find it easy to run but not retail investors? In practice, that is what he is saying. In a systemic run – or a period of heightened systemic unease – it is very easy for wholesale investors to find a safe asset (whether exchange settlement account balances for banks, or government bonds/ Treasury bills for others). It isn’t for retail investors. And recall that in New Zealand we have no deposit insurance.

If I’m uneasy at all about the idea of making available an eNZD (or AUD) for retail users – a basic store of value/means of payment technology with no credit risk – it is that demand would be very limited in normal times, and that if there ever was a systemic crisis it might prove very hard to scale the product quickly to adequately demand. There are probably ways of resolving that concern, but it does need more work.

One other concern I’ve heard expressed if this if the central bank issued retail e-cash it would create a reinvestment problem – what would the Reserve Bank buy and hold on the other side of its balance sheet (with associated credit and quasi-fiscal risks). This is mostly a non-problem for several reasons:

- normal times demand is likely to be low, and can be kept fairly low through pricing,

- retail e-cash would probably go hand in hand with steps to reduce the stock of physical cash (and central banks already reinvest the proceeds of the sale of notes),

- in a crisis, central banks have this issue anyway – the substantial liquidity injections typically involve material credit risk anyway, and

- in practice, many central banks typically reinvest the proceeds of note issue (or subscribed capital) in government bonds (predominant approach in New Zealand) or foreign reserves (typically mostly the government bonds of other countries).

With an integrated approach to gradually reduce the stock of physical currency, while making available a retail e-cash product, I would expect that if anything central bank balance sheets would shrink somewhat (especially in Australia, with a higher currency to GDP ratio) rather than grow. Steps in that direction would:

- help deal with the zero lower bound problem,

- reduce the tax evasion etc issues apparently associated with large holdings of physical cash, and

- provide ordinary citizens with the same sort of basic risk mitigant/payments product open to banks.

Finally, I said that one of Phil Lowe’s counter-arguments was mostly rhetorical. That was this one

The point here is that exchange settlement accounts are for settlement of interbank obligations between institutions that operate third-party payment businesses to address systemic risk – something that is central to our mandate. A decision to offer exchange settlement accounts for day-to-day use would be a step into a completely different policy area.

Well, yes, as conceived at present exchange settlement accounts are about interbank dealings. That is a core part of the RBA’s (and RBNZ”s) responsibilities. But the provision of basic “outside money” – credit risk free – has also long been a core part of both central bank’s responsibilitiies. Retail e-cash helps fulfil that part of those mandates in a technological age.

The lower NZ holding of currency/GDP at 2% compared to that of AU at 4% is astonishing. The auditor in me is put on enquiry – and – I just don’t believe it. Then I have periodically expressed doubt about official NZ data

The AU chart rises post 2008 GFC – as one would expect – even though Federal Government calmed the waters by providing a Bank Guarantee – and yet it still rose in spite of that comfort

The NZ chart suggests there are very large and very different social influences at work. To be 50% lower is cause for assuming NZ’ers are far more relaxed about the GFC. Perhaps the silence and poor penetration of the MSM is a disturbing consideration.

AND

It suggests the understanding by the populace of the OBR is poor to non-existent – One would expect when the RBNZ or whoever finalised the formulation of how the OBR would work the graph should have spiked up – it didn’t – I really don’t think the NZ public is that stupid – the problem of course is where and how to hold cash

In my own case in response to the OBR I continue to hold my cash reserves in AU to take advantage of the bank guarantee – can’t imagine I am alone

LikeLike

Greece when they exercised their version of the OBR had a cut off, ie Depositors at bailed-out Cyprus’ largest bank will lose 47.5% of their savings exceeding 100,000 euros ($132,000).

As part of the bail-in of Bank of Cyprus, depositors taking losses — estimated roughly at around 4 billion euros — will get shares in the bank. Those depositors hardest hit are pension funds belonging to employees for state-run companies, followed by private savers of which some of the biggest are Russians.

LikeLike

We did think about this issue around the time that we were pushing a numbers of payment system reforms, including the move to real time gross settlement. There is certainly an argument that there is a public interest in allowing electronic access to central bank money as well as (or potentially instead of) physical access. And there must be significant efficiency gains available, given the considerable costs of producing, storing, handling and guarding physical currency.

However, we were not all transacting on-line back then (and we still are not) and we left the idea for the time being. As an alternative, we encouraged the banks to introduce same-day cleared payments as an alternative to (somewhat problematic) bank cheques. This gave ready public access to a low-credit-risk method of undertaking large transactions. While SCPs were not “as good as cash”, they were close enough for most purposes.

The fact that some of the demand for cash derives from its anonymity is a conundrum. No central bank likes to be a facilitator of illegal activities, and, indeed, much effort has gone into the detection and prevention of money laundering and the like. If central bank eMoney were issued in a form where it was traceable, some of the demand for it would be driven into the likes of bitcoin. Would that be socially desirable??

LikeLike

Thanks for those comments Peter. According to the RB analytical note, Bitcoin transactions will in effect be traceable back to individuals – and of course those vehicles look much riskier (on multiple dimensions) than central bank e-cash,

SCP (a welcome innovation) seems to me to meet the payments assurance need, but doesn’t deal with the store of value issue.

LikeLike

The IRS has been putting pressure on the various Bit coin facility provider to provide details. Limited details have been provided but wholesale detail is still being subject to lawyers blocking full access.

However as far as the IRS is concerned Bitcoin is a speculative investment and subject to tax on value realisation, ie in the act of trading goods and services will trigger tax liability.

LikeLike

I just rediscovered this fine presentation.

https://www.rbnz.govt.nz/research-and-publications/speeches/1996/speech1996-05-16

The specific issue is referred to in Para 19

I am pretty happy that there is little I would change 20+ years on

LikeLike

Excellent article. Thanks. 21 years have elapsed. Did that ever go anywhere. Have there been any further investigations. Papers. Smiled at the 1996 “purse” concept. Now called the Bitcoin “wallet”

Where is the RBNZ on this today?

LikeLike

As I’ve noted in these posts, the RB has recently said it has work underway. I have OIA’ed what they have done already, and if anything comes of that I will link to it here.

LikeLike

[…] Sweden, Australia, we now have some bit from New Zealand as well. Though, unlike the Sweden and Australia posts which were based on speeches of their […]

LikeLike

thinking aloud: could an eNZD impose quasi ‘market discipline’ on RBNZ macro-prudential policy assuming a switch from a commercial deposit to an eNZD signalled systemic risk concens? granted, it would typically be a quick fire switch but a slow leak could serve as a red flag that prudential policy might be lagging unsustainable risk taking.

LikeLike

it could be the sort of signal you suggest, altho for most banks you’d expect a wholesale run to have got going earlier, and for the bank concerned to be finding it increasingly difficult to raise any term funding – at least on terms that don’t themselves signal crisis.

LikeLike

Michael, great set of blog posts on the topic of e-NZ.

“The issues and risks are pretty similar for both options, and I favour (provisionally) something like the second option.”

Let me point out the benefits of the first; electronic banknotes. Society gets all the benefits of the second, including the ability to set a negative interest come the next crisis, while also getting the same level of privacy as banknotes. So when banknotes are eventually replaced, at least society has some form of private payments media.

There is a thorny trade-off between the use of cash by tax-payers who want legitimate privacy, and the use of cash by non-taxpayers to evade taxes. One way to strike a balance between the two is to reduce the largest note denomination to $20, as you suggest in your previous post. This burdens users with higher storage and handling costs and may somewhat mitigate tax evasion.

But there are potentially superior methods for striking this balance via electronic banknotes. The advantage of an electronic banknote over cash is the ease of paying (or docking) interest. A permanently negative interest rate of -0.25% or so would act as a toll on users of anonymity, the extra seignorage flowing to the government acting as an offset to revenues lost from tax evasion and the costs of policing against cash-using criminals.

Central bankers have accidentally wandered into being society’s sole provider of anonymous payments, a role they didn’t anticipate years ago when they monopolized the issue of banknotes. My belief is they should recognize privacy as a core part of their responsibilities, which means that upgrading to electronic banknotes may be a mandate worth investigating.

LikeLike

Thanks. I agree with the argument for privacy, but I suspect societies are going to be increasingly intolerant of it.

LikeLike

[…] Central bank e-cash – croaking cassandra […]

LikeLike

[…] On central bank’s e-cash https://croakingcassandra.com/2017/12/14/central-bank-e-cash/ […]

LikeLike