It is another glorious day in Wellington – I always reckoned a 2 degrees warmer Wellington would be a good thing – and there is Christmas shopping to do, but I couldn’t let the latest speech from the Reserve Bank go by without comment.

It is presented as a speech by “Reserve Bank Governor Grant Spencer”. Fortunately, most of the media haven’t fallen for that line – which they’ve tried on in a number of recent documents. If Spencer is anything, he is “acting Governor”, and no more.

How do I know? Because Parliament was quite clear that

The Governor shall be appointed for a term of 5 years

And when he appointed Spencer, Steven Joyce was quite clear that the appointment was for six months only. He only ever claimed to be appointing an “acting Governor” – who can, under certain conditions, be appointed for only up to six months.

As it happens, even that appointment is almost certainly unlawful. The Act is also pretty clear that an acting Governor can only be appointed when a Governor leaves office before his or her term has expired. That wasn’t the case here. In other circumstances, the Minister and the Board are simply expected to get on and make a permanent appointment, so that a new permanent appointee can take office when the previous appointee’s term expires (a date known, in this case, for the previous five years). It might not be ideal phrasing, but it is the law, and if there was a problem – as there was in the case, around the election – either the law needs to be worked within, or to be changed by Parliament.

But we now have the strange situation where the Minister who appointed him thought Spencer was acting Governor, while Spencer himself now seems to purport to be – not just have the powers of – Governor. As I’ve been doing for the last couple of months, I will continue to describe him only as “acting Governor”, or “the economist purporting to be acting Governor”.

Whatever his label, there is a bit of sense of relief that Graeme Wheeler is gone and that Spencer – someone well-liked and generally more open – is minding the store. But his speech earlier this week, on monetary policy and the challenges of low inflation, still left a great deal to be desired. I suspect it wasn’t intended this way, but in practice it amounts to not much more than excuses for not keeping inflation near target for the last five years, partly by attempting to obscure a New Zealand debate with the (somewhat different) issues some other advanced countries face. And, of course, whatever the merits of Spencer’s views, he’ll be gone in little over three months and as yet we have no idea who the new single decisionmaker will be (let alone who will eventually serve on the new statutory monetary policy committee to be put in place next year).

There is some interesting stuff in the speech though. Most notable perhaps was the number of references to unemployment. Often enough Reserve Bank monetary policy documents mention it barely at all – the Bank even tried to displace it with a new (but sadly ill-fated) labour market capacity indicator of its own devising. For decades, the capacity variable in the Bank’s inflation models was (its estimate of) the output gap, and there were typically lots of references to it in speeches or Monetary Policy Statements.

But in Spencer’s speech – his first as “acting Governor”, and the first under the new government – there is but one reference to the output gap (and then only in abstract terms) and 17 references to “unemployment”. And to think that some people reckon it doesn’t make much difference who is appointed Governor.

But the odd thing is that much of the speech is devoted to making the case that the unemployment rate (itself) hasn’t been much help in explaining inflation in recent years. Which might be true, to some extent, but so what (at least when considering events of the last decade)? After all, for years the Bank told us they didn’t put much weight on the unemployment rate, didn’t think they could fix on a NAIRU etc etc, and that we really should be focusing – as they did – on the output gap and a broader suite of high-tech capacity indicators. It might even – if valid – be an argument for not putting too much specific focus on a specific or precise unemployment rate in the new monetary policy regime the government envisages – but that isn’t the case Spencer makes, and weirdly he suggests that the Bank is already (since when?) putting more weight than previously on employment indicators. It isn’t very coherent, in a New Zealand context.

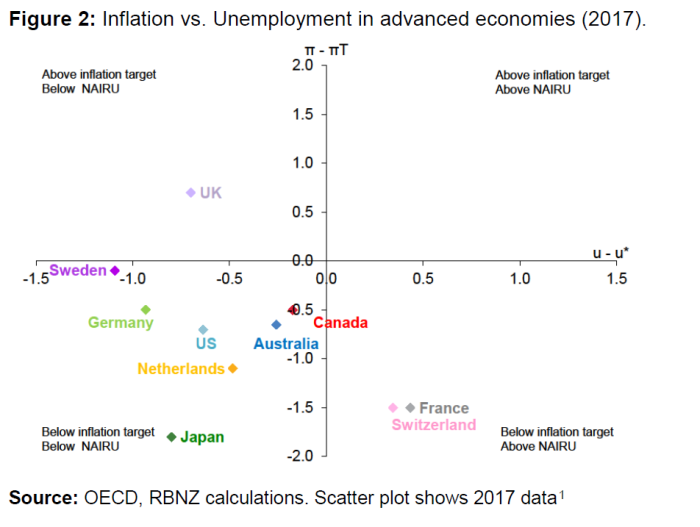

This chart ran in the recent Monetary Policy Statement (when I didn’t get round to commenting on it) and it appears again in Spencer’s speech.

It is the sort of chart the word “chutzpah” might have been invented for. They use it to try to suggest that much of the advanced world is “stuck” in a situation in which the unemployment rate is below the sustainable rate (a NAIRU) and yet inflation is also below target.

There are a number of odd things about the chart. For example, they include three separate observations for Germany, the Netherlands, and France, even though all three are in a common currency (and thus common monetary policy) area. And surely it would have been more enlightening to include the other advanced countries with independent monetary policies (eg Norway, South Korea, Israel, Iceland? There is also no place at all for inflation expectations in the story the Bank is trying to tell in the chart.

But the biggest, most obvious, omission is New Zealand. And where would New Zealand fit on the chart? Well, core inflation is about half a per cent below target and on most estimates – even on the most recently quarterly unemployment observation (4.6 per cent) – the unemployment rate is still above an estimate of the NAIRU. If these relationships hold at all, there are lags, and the average unemployment rate for the last four quarters was 4.9 per cent. By contrast, before the major revision downwards to the HLFS unemployment rate last year, the Reserve Bank had a NAIRU estimate of 4.5 per cent in its models (a part of that model that had no implications for the inflation forecasts), and after those revisions, Treasury published estimates suggesting they thought the NAIRU was now nearer 4 per cent. In other words, for now at least, New Zealand still belongs in the bottom right quadrant of the Reserve Bank chart, the one in which there isn’t much of a mystery or puzzle at all: with inflation below target and unemployment above a NAIRU, a typical response – in an inflation-targeting framework – would be to cut the OCR. Switzerland and France can’t do that – Swiss interest rates are already negative, and France can’t control interest rates – but New Zealand could. It is just that the Reserve Bank chose not to.

In the chart the Bank uses OECD estimates of the NAIRU. That is understandable – they are the only consistent cross-country estimates I’m aware of – but not one without its problems. For example, somewhat unusually, the OECD thinks the New Zealand NAIRU this year is still in excess of 5 per cent. Then again, if you believe the OECD’s estimates, unemployment in New Zealand has been below the NAIRU for almost the entire 21st century so far (rising just very slightly above only in 2009, 2010, and 2012). It simply doesn’t ring true.

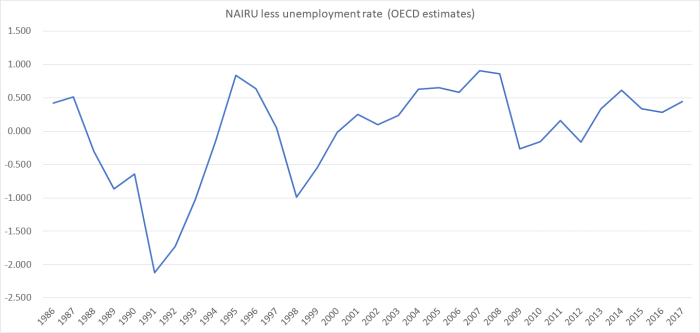

The Reserve Bank’s next chart in this area is this one

The suggestion is that there was a relationship between unemployment and inflation in the 2000s (when they also didn’t use the relationship), but that it has disappeared (for now at least) in the last few years.

Given that the relationship (even in the previous decade) wasn’t tight by any means, and many of the higher inflation numbers related to things – eg oil shocks and short-term exchange rate movements – that didn’t have much to do with New Zealand unemployment rates, I didn’t find the chart overly persuasive. Moreover, since everyone recognises that the NAIRU changes over time – with things like demographics, labour market regulation, some hysteresis etc – even the theoretical relationship shouldn’t be with the unemployment rate itself, but with the gap between the NAIRU and unemployment rate. I suspect the Bank is currently feverishly working on a suite of time-varying NAIRU estimates – to reflect the new government’s interest – but there is no hint of those in this speech.

Ideally, one might want to look at something more like an unemployment gap estimate against deviations of core inflation from target (what the Bank was trying to do, in a snapshot) for other countries in the first chart). As I’ve already said, I don’t have any confidence in the OECD’s levels estimates of the New Zealand NAIRU, although the changes in the associated gap from year to year might not be too bad. For now, it is all I have.

So in this chart, using annual data (all we have for the unemployment gap) I’ve shown the deviations of sectoral core factor model inflation from the midpoint of the inflation target and the OECD estimate of the unemployment gap from 1993 (when the core inflation data start) to 2016 (each dot is one year’s data).

Even including the most recent years (the furthest left observations) there is still a relationship there, albeit not a very tight one. Then again, it wasn’t very tight – although a bit more upward sloping – when I deleted those most recent years. No doubt the Bank could – and perhaps is doing so privately – do this sort of analysis in a more sophisticated way.

I’m not suggesting there are no puzzles about New Zealand’s inflation performance in the last few years. But simply plotting the raw unemployment rate (and not even looking at, say, the underutilisation rate or the gap) against headline inflation isn’t going to tell you much – we aren’t in 1958 now (when Phillips wrote) and, apart from anything else, inflation expectations matter.

For the last couple of years, the Bank has consistently tried to tell a story of how inflation expectations are firmly anchored at the 2 per cent midpoint of the inflation target. That has always been a questionable proposition, especially as regards the sorts of expectations that might affect wage and price setting behaviour. Their favoured two-year ahead measure of inflation expectations is now around 2 per cent, but a decade ago it was averaging almost 3 per cent. Household inflation expectations are also lower than they were. Again, that isn’t very surprising because a decade ago the Reserve Bank wasn’t seriously aiming to deliver inflation at 2 per cent (the target midpoint): we might have been happy enough to take it if inflation had got there of its own accord, but our projections (the Governor’s choice) rarely showed inflation dropping below 2.5 per cent any time soon. Actual core inflation was up around 3 per cent.

And these days? Well, core inflation hasn’t been anywhere near 2 per cent for years now – persistently below. And although the Bank consistently talks of getting inflation back to 2 per cent, it hasn’t done so, and for several years consistently erred on the hawkish side, with constant talk of wanting to “normalise” interest rates, and actually following through on an unnecessary and ill-judged tightening cycle. Even now, “normalisation” got a lot of attention in last week’s FSR (although mercifully absent from the speech), and the Bank constantly talks about not wanting to act aggressively to get inflation back to target. Any rational observer would not only assume inflation will be materially lower than it was, but that the Bank is quite relaxed about that (it more or less says so). The practical target isn’t really 2 per cent – any more than it was, on the other side, 10 years ago – but something a bit lower.

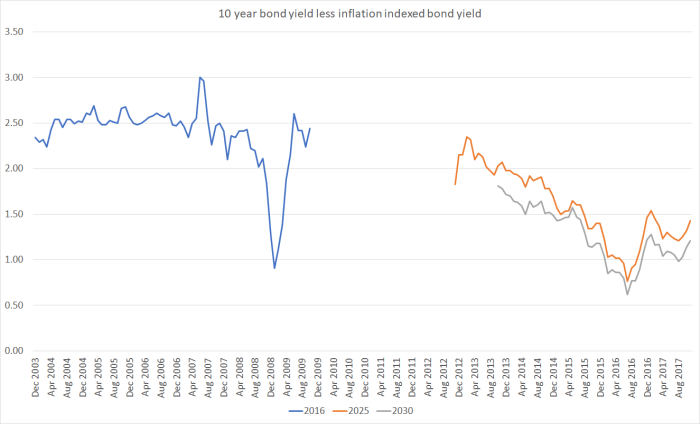

The Bank must hate data from the inflation-indexed bond market (because it never engages with it in any of its publications), but the gap between indexed and conventional bonds is not inconsistent with my story. Interpreting that data in fine detail isn’t easy. For a long time, we had only a single indexed bond (matured in Feb 2016), and by late in its life headline inflation (eg the GST change in 2010) mattered much more than the medium to long-term outlook). These days there are several indexed bonds, but they have fixed maturity dates while the Reserve Bank’s published “10 year bond rate” has, in effect, a maturity date that moves through time.

But consider this chart, showing the gap between yields on successive indexed bonds and the conventional 10 year bond rate.

In the years prior to 2008 (when the indexed bond still had 10 years to run), the implied inflation expectation was around 2.5 per cent. As noted earlier, that wasn’t too far from how we were running things in practice. What of now? It is late 2017, so 10 years from now is roughly half way between 2025 and 2030, the two indexed bond maturity dates either side of 2027. In November, the average gap between orange and grey lines was 1.3 per cent, and for the year to date the average gap has been 1.2 per cent.

No doubt, there are all sorts of idiosnycratic things going on, so these breakeven inflation rates may not be “true” inflation expectations (as, for example, they weren’t in the midst of the crisis in 2008). There are, for example, a lot of inflation bonds on the market, and it is possible that Treasury has somewhat glutted the market. My point simply is that if one wants to make sense of relationships between unemployment (or other capacity measures) and core inflation over the Wheeler years, it is wilfully blind to simply ignore a story about changing inflation norms.

The next chart is just a rough and ready thought experiment. What if, when Graeme Wheeler took office in September 2012, inflation expectations were genuinely about 2 per cent, and people really thought that was what the Reserve Bank was serious about. The indexed bond yields – rough and ready as they are – suggest that isn’t wildly implausible. And, say, now people really think the target (for sectoral core inflation) is more like 1.3 per cent – the most recent actuals are 1.4 per cent. Then the chart just shows the relationship (using quarterly data) between the unemployment rate and the gap between actual core inflation and an implied target taken by interpolating from 2 per cent in 2012 to 1.3 per cent now.

I”m not suggesting that is the “true” relationship, but it looks like an idea worth taking more seriously than the Bank has thus far been willing to do in public. After all, expectations adjust gradually in most circumstances. It seems negligent, or deliberately obtuse, not even to engage with the possibility.

After all, the “acting Governor” – I almost slipped there and initially typed it as Governor – ends his speech with the suggestion that

To the extent that the leverage of monetary policy over domestic inflation may have reduced, this suggests a cautious approach when responding to inflation deviations from target and careful attention to our assessment of economic slack. It may be appropriate for monetary policy to put relatively more weight on output, employment and financial stability relative to inflation.

Why wouldn’t a reasonable observer conclude that the Bank isn’t really targeting 2 per cent (although it might be happy enough to get there by accident) and continue to adjust their expectations and behaviour accordingly.

With a new government planning to revise the Bank’s mandate to increase the Bank’s focus on employment/unemployment, Spencer’s line would almost be some sort of sick joke if it weren’t so serious. When the unemployment rate has been above New Zealand estimates of a NAIRU for nine years, and when the economic recovery (average growth in real per capita GDP) has been so muted, you might reasonably suppose that the government would have been expecting the Bank to do its job more energetically – which would involve getting inflation back to target, and in the process finally delivering an unemployment rate around the (unobservable NAIRU) and even a bit faster real GDP growth. But Spencer – with no mandate whatever, but presumably with the support of his colleagues, Bascand and McDermott – wants to tell us that their idea of putting more focus on “employment and output” than in the past has been to deliberately deliver such weak cyclical outcomes – ie deliberately accept higher unemployment/lower employment than is strictly necessary. And the implicit promise is more of the same to come, at least if people like them are left in charge. I hope the Minister of Finance is paying attention, and that his recent talk of possibly removing the midpoint reference from the PTA wasn’t a sign that he has begun to buy into this Wheelerish mentality (even if given a glossed up public face by his colleagues now that they are minding the store).

Does it matter to compare an economy that moves to a service base versus manufacturing. To work in hospitality and tourism you have to be presentable? Then there is the language factor (China being our second source of tourists)?

Only 10% work in that sector so not a big factor?

LikeLike

I think 10% is directly employed but indirectly substantially more. If you wander down main roads like Dominion Road or Mt Albert Road or out to Chowick, you have to add in the businesses, the retail shops, restaurants, the lawyers, accountants, real estate agents etc

LikeLike

The sectoral shifts have been happening across the advanced world. I’m not sure it is likely to affect the activity/unemployment vs inflation short-term relationship – the relevant channel isn’t clear – but maybe.

LikeLike

To be fair, Grant Spencer is described as Acting Governor on the organisation chart on the RBNZ website:

https://www.rbnz.govt.nz/about-us/organisation-chart-and-senior-management

LikeLike

Perhaps Grant Robertson has given Grant Spencer the impression that he is the Governor. Perhaps a handshake and a nod with a follow up contract at the appropriate time.

LikeLike

Unless he is going to change the Act he couldn’t appoint Grant S permanently – as he is already 65 and an appointee has to be able to serve for 5 years, age barred at 70. Plus, Grant S has already announced he is retiring.

LikeLike

That is encouraging (and what i’d Expect) but leaves the mps, fsr, and this speech as a bit puzzling. I suspect they are trying to reinforce an image of legitimacy etc

LikeLike

Will no one rid me of this turbulent priest?

LikeLike

Not too sure why the reference to priest? I thought these days it is the turbulent Imams that radicalize to cause turbulence.

LikeLike

Assuming yours was a genuine query:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Will_no_one_rid_me_of_this_meddlesome_priest%3F

Not sure whether Michael appreciates his equivalence to Thomas Becket!

LikeLike

I did note the reference, but I’m pretty sure I’ll be regarded as more irrelevant than troublesome – and of course, Henry apparently never intended to be taken seriously.

LikeLike

I love your blog, even though the more technical discussions sometimes phase my uneducated brain.

It seems to me that unemployment in NZ is surely better measured by the labour underutilisation rate rather than by the “employed for one hour per week” measure? A quick walk around any lower socio-economic area of NZ during a weekday will show you a lot of people are out of work. Surely wage pressures won’t grow while there is a limitless pool of cheap labour available from overseas as well as many people who want more work but can’t find it?

Would lowering the OCR another %1 say really help growth that much now? Would business really invest more? Would a bit less on interest payments on my mortgage make me spend more (more likely I would double down on paying it back)? Are households a bit fed up with taking on more debt? My elderly mother would be spending less to as her deposits would earn less. Bond holders would earn less. People would factor in lower rates into their prices.

I have listened to some economists like Summers and Blanchard recently say that now is the era of fiscal policy. I would love to read your views on that. Or is lowering the OCR enough?

Many thanks for your blog. Makes a change from the “shallow” pieces you seem to get in the mainstream.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Lowering the OCR would definitely boost business investment. The problem is that our banks are a monopoly and lowering the OCR by 1% may likely only result in at best 0.25% fall in real interest rates if the banks decide to pass any crumbs to us borrowers.

LikeLike

In the event of a need for a 1% OCR cut, businesses, that I know and have known, would not be boosting any investments, they would be battening down the hatches and tightening the purse strings

LikeLike

depends on the trigger surely. often enough cuts come because business conditions are already worsening. if last week’s fall in business confidence continues we may yet find ourselves in that position. even then, lower interest and exchange rates (eventually) tend to act as a stabilising force

LikeLike

A 1% cut from 10% down to 9% would stimulate completely different business reasoning compared to a 1% cut from 1.75% down to 0.75%

While a 0.75% interest rate to a debt-free business who would be prepared to take on debt it is also the highest risk of the two conditions

LikeLike

A 1% drop by the banks if they follow the OCR coupled with a drop in the LVR restrictions to 30% equity would increase working capital availability. Any business that wants to grow would either look for equity or look for debt.

The resultant fall in savings deposits would go into higher risk equities seeking higher yields boosting again investments.

But there is an anchor that the RBNZ has placed on banks which is tied to available local deposits in order to increase your local lending books. This dependence on local savings by the banks limits the lending availability and limits the large multinational banks from competition in the local NZ market. No wonder all these international banks have not been able to deliver lower interest rates as they have to attract local savings and offer higher interest rates in order to attract local savings before they can build a NZ lending book.

LikeLike

Thanks for the comments – there is a difficult balance to strike across (a) the topics that interest me, and (b) the differing aptitudes and interests of different classes of readers (my former RB colleagues prob constantly lament the lack of sufficiently technical treatments.

Re underutlisation rate, yes I agree if we want some sort of measure of thre absolute unemployment rate. Macro people mostly use the official series because it has the longest time series.

Re fiscal policy, I might come back to in a separate post, but the issues here are different than those in most countries. On the one hand we have more “fiscal space” – lower debt – but on the other we don’t need to use fiscal policy as interest rates are still a reasonable way clear of the lower bound (say -0.75 per cent). We may well need that fiscal space in the next recession.

On the question of how much difference would lower interest rates make, the only possible answer is “some, and in the right direction”. One of the main channels would be through a lower exchange rate. From a monetary policy perspective, the higher inflation is the goal – lifts to growth and lower unemployment are largely welcome side-effects.

LikeLike

On previous occasions when the rate was below NAIRU, what was the impact on the macroeconomy? In other countries I understand wage gains and productivity have been good, and haven’t always spilled over into inflation.

LikeLike

yes, those are the things than could reduce NAIRU itself, altho demand management can move U relative to NAIRU

LikeLike

We clearly saw wage and price inflation pick up here in the mid 00s. In other countries, my impression has been that wage inflation is really just beginning to pick up. Re productivity, you may recall a post a few weeks ago here showing that wage inflation here has been running well ahead of (non-existent) productivity growth. In effect, our real exchange rate is getting further out of line.

LikeLike

…just hope the MoF is also attuned to the reality that its “Not Actually Inflation which Reduces Unemployment” (the other NAIRU) but rather policies that aim to improve people’s incentives toward accessing education, apprenticeships, skills training, regional mobility etc.

LikeLike