What will happens if – perhaps “when” if we take a long enough horizon – a major Australian bank fails isn’t at all clear.

We went through a phase of failures and near-failures a generation ago, after the post-liberalisation boom and (spectacular) bust. On the Australian side, there were the failures (in effect, bailed out by governments) of the state banks of Victoria and South Australia – the latter bank had operations in New Zealand. Westpac – operating as a single entity on both sides of the Tasman – came under some pretty severe pressures. And on this side of the Tasman, we had the failure of the DFC and the two episodes in the failure (again bailed out by the government, the primary owner) of the BNZ. (In both countries, some new entrant foreign banks also lost a lot of money, but they weren’t really the problem of governments and regulatory authorities in Australasia).

In that episode (or succession of episodes), handling the failures (or threat of failure) was almost entirely a matter for the home authorities – those where the bank concerned was based. That was so even when there were substantial losses on the other side of the Tasman (eg many of BNZ’s losses were on the loan book it had built up trying to buy its way into the Australian market).

Things were easier and clearer in that episode. In particular, the banks that actually failed were all government-owned (wholly or primarily) to start with. And in Australia, the failures were of second-tier institutions: we (fortunately) never got to see how a Westpac failure would have been handled. And at the time, the New Zealand and Australian banking systems were also much less intertwined. Westpac and ANZ had substantial New Zealand operations, but NAB and Commonwealth Bank were hardly here at all, and we had fairly large banks that weren’t active in Australia (the Lloyds-owned National Bank, Trustbank, Countrywide). BNZ was the largest bank in New Zealand, but although the BNZ’s operations in Australia were important to them, they were not very important to Australia. BNZ was clearly our problem.

These days, by contrast, our banking system consists of the operations of the four big Australian banks, state-owned Kiwibank, and the rest don’t matter much at all (whether retail or wholesale). And for the Australian banks, New Zealand exposures are typically the largest chunk of the non-Australian assets of the respective banks. In ANZ’s case, almost 20 per cent of the group’s assets are in New Zealand. Our problems are their problems, and their problems are our problems.

But the interdependence isn’t symmetric: not only is Australia much bigger than New Zealand, but all the banks are (ultimately) Australian-owned and based. Things would look rather different if, say, one of the four big Australasian banks was owned and based here. And our legislative approaches are different too: Australian had explicit statutory preference for the claims of Australian depositors (and, more recently, deposit insurance, but that is a different issue), while under our legislation all creditors are treated equally. That longstanding depositor preference rule was one of the main reasons why some years ago (it must be getting on for 20 years now) we insisted that the local operations of Australian banks taking material amounts of retail deposits had to be locally incorporated (ie operate through a New Zealand subsidiary). The proceeds of the New Zealand subsidiary’s assets were to be available to meet its own explicit liabilities, not just be part of a wider trans-Tasman pool.

On paper, the New Zealand subsidiary is pretty fully separable from the parent. Should the whole banking group fail, New Zealand authorities can decide how to handle the New Zealand subsidiary independent of what the Australian authorities decide (although in both countries, legislation commits each country to take account of the financial stability interests on the other). If the subsidiary also failed we could choose to bail it out, or not. And if the subsidiary was strong, even though the parent was in trouble (say there had been a particularly severe shock specific to Australia), the subsidiary would be capable of keeping on operating here. That separability comes at a cost, but it might well be technically workable. In principle, we could apply the OBR mechanism to the (failed) New Zealand sub of an Australian bank (the stated preference of the Reserve Bank and the previous government) even if the Australian government bailed out the parent (the generally expected approach under successive Australian governments).

In practice, it isn’t very likely. And everyone in the relevant government agencies on both sides of the Tasman knows it. Should the whole of a banking group be in trouble, it is much more likely that the Australian government will push (very strongly) for a bail-out of the entire group, and will put a great deal of pressure on the New Zealand government to contribute to such a bailout. What is their leverage? Well, on the one hand, there are always large numbers of issues on the boil between the two countries at any one time – don’t play ball on something that really matters to Australia, and we’d find ourselves exposed to bad outcomes in some other areas, and damaged relationships over time. And on the other hand, there would be straightforward domestic political pressure here: how likely is a New Zealand government to let the depositors of ANZ New Zealand lose money, while the news headlines tell of the Australian government bailing out in full those of ANZ Australia? And from the Australian perspective they won’t want a major subsidiary, carrying the same name, failing, even if the Australian operations themselves are ringfenced – the headlines won’t look good with the investor base in New York, London, or Tokyo.

In sum, it is much more likely that if one of the major Australian banks fails, (a) it will be bailed out at a group level, and (b) there will be a great deal of pressure for New Zealand to participate in a bail-out in some form or other. The details will be haggled over at the time, under intense pressure, and with active high-level political engagement. Australia, for example, would probably prefer we put in money to help recapitalise at a group level (while the parent then recapitalises the NZ sub). Our authorities might prefer a clean break in which we took, and recapitalised the sub, and had control over what happened down the track. What actually happens would depend on, inter alia, the key individuals at the time, the wider state of political relations between NZ and Australia, perhaps where the source of the failure primarily lay (NZ-centred losses or not), on the global environment, and on whether this particular failure was perceived to be idiosyncratic, or potentially the first of a sequence.

One of the issues the Europeans (in particular) have been grappling with since the 2008/09 crisis has been the ability – fiscal capacity – of single countries to stand behind (“bail out”) large international banks that are based in their countries. It isn’t really an issue in the United States (for example) where the banks are not that large (as a share of GDP) and the country itself is big. It is potentially a different issue in, say, Switzerland or the Netherlands – and since the crisis, the Swiss authorities have been taking steps to lower the relative size of the international banks based in their country.

One of the academics who has done a great deal of work in this field is Dirk Schoenmaker, of the Rotterdam School of Management, who has been in New Zealand for the last couple of weeks as the Reserve Bank/Victoria University professorial fellow. When the Reserve Bank has these visiting fellows, Treasury tends to “free ride” and use the opportunity to host a public guest lecture by the visitor (which used to annoy me a little when I was at the Bank – it was our money funding the visit – but for which I’m now grateful).

Last Friday, Schoenmaker gave just such a lecture at The Treasury on exactly this issue: can small countries cope with international banks based in their country, and the risk of them failing. His published paper on the issue is available here. This is from his abstract.

While large countries can still afford to resolve large global banks on their own, small and medium-sized countries face a policy choice. This paper investigates the impact of resolution on banking structure. The financial trilemma model suggests that smaller countries can either conduct joint supervision and resolution of their global banks(based on single point of entry resolution) or reduce the size of their global banks and move to separate resolution of these banks’ national subsidiaries (based on multiple point of entry resolution). Euro-area countries are heading for joint resolution based on burden sharing, while the United Kingdom and Switzerland have implemented policies to downsize their banks.

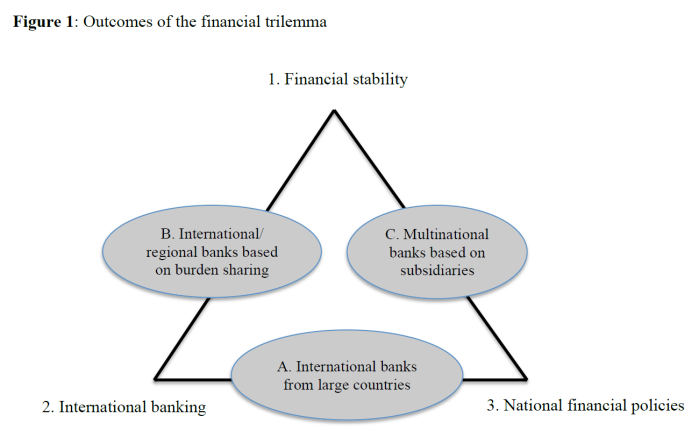

This is his trilemma

You can, he argues, have any two of these dimensions but not all three if you are a small/medium country. That reasoning seems sound. I’m less sure about what follows from it.

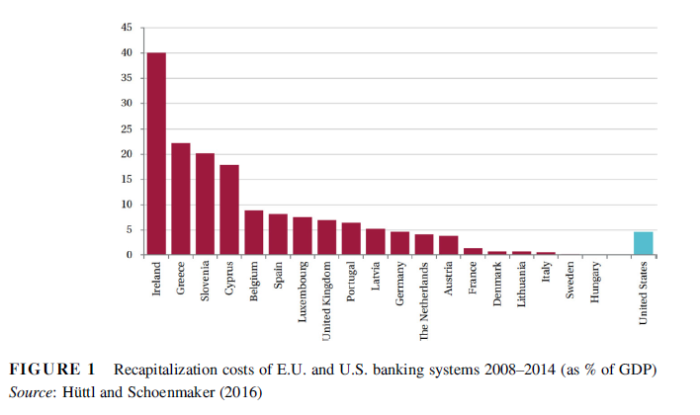

First, what can individual countries afford to do (as bailouts) if they want to? Schoenmaker does quite a bit of analysis of the last series of crisis (2008 and after) and concludes that the most any country can really spend on a bailout is 8 per cent of GDP. This is his chart

As he notes, the first four countries on the left of the chart couldn’t cope themselves and needed either IMF or EU support, and Spain also needed external assistance. But all these countries were in the euro-area, and thus not only lost the capacity to adjust domestic interest rates for themselves, but also couldn’t do anything to adjust the nominal exchange rate. By contrast, the UK’s bailout costs – not that much lower than Spain’s – never ever raised any serious questions about the UK’s fiscal capacity. And that was with a far higher starting level of public debt (as a share of GDP) than, say, Ireland had.

As he notes, the first four countries on the left of the chart couldn’t cope themselves and needed either IMF or EU support, and Spain also needed external assistance. But all these countries were in the euro-area, and thus not only lost the capacity to adjust domestic interest rates for themselves, but also couldn’t do anything to adjust the nominal exchange rate. By contrast, the UK’s bailout costs – not that much lower than Spain’s – never ever raised any serious questions about the UK’s fiscal capacity. And that was with a far higher starting level of public debt (as a share of GDP) than, say, Ireland had.

So his analysis looks to be quite useful in an intra euro-area context. Belonging to the euro – whatever advantages it may bring – involves a substantial sacrifice of national flexibility in a crisis. And so the logic of the direction Schoenmaker is calling for – and which the Europeans are moving gradually towards – involving (at least for big international banks) unified supervision and loss-sharing (across national boundaries) in the event of failure and bailout, seems to make quite a lot of sense. If I were Dutch, I’d probably be rather keen on the idea.

But Schoenmaker also argues that the model is directly relevant to this part of the world. In particular, he shows a table in which the cost of recapitalising (ie replacing existing capital) of the three largest Australian banks (he uses the top-3 banks in each area he looks at) would be around 7.6 per cent of GDP. That is close to his 8 per cent “fiscal space” threshold, and thus he argues that Australia may be only barely able to cope with a systemic financial crisis in this part of the world. Part of that recapitalisation burden would, on these numbers, include the overseas operations, the largest of which are typically in New Zealand.

Schoenmaker has written a new paper specifically on the idea of a possible trans-Tasman banking union. It is still in draft, and isn’t yet available on his website, but he has given me permission to make it available here. Schoenmaker on Trans-Tasman Banking Union

It is worth reading, both for the coverage of the ideas, and because the current draft already incorporates comments from Wayne Byres, the head of the Australian Prudential Regulatory Authority (APRA).

I don’t really buy the potential fiscal incapacity argument in either Australia or New Zealand. Both countries have very low levels of public debt (Australia’s even lower than our 9 per cent net government debt, properly defined), and plenty of capacity for the exchange rate to adjust in a crisis (not just against each other if necessary, but against the wider world). Neither country is hemmed in as (say) the Irish were – “prohibited” by various EU agencies from allowing any private sector bail-in, even of wholesale creditors, in the midst of the crisis.

But set that to one side for the moment, how might his proposed trans-Tasman banking union work? And why is not likely at all to be established?

Schoenmaker doesn’t set out precise details in his paper, but from his various papers and presentations it is clear that he draws an important (and correct) distinction between non-binding memoranda of understanding and the sorts of binding pre-committed burden-sharing arrangements he is talking about. As he notes, there is a lot of contact between New Zealand and Australian officials in this area, culminating in the Trans-Tasman Banking Council (TTBC). There is probably a fair amount of goodwill, statutory provisions to encourage looking out for each other, and the various agencies even “war-game” crises from time to time. But none of this commits anyone (or their political masters, who change) to anything in a crisis. In crises – as in 2008/09 – it is largely every country for itself.

And so what he seems to envisages is a binding treaty entered into by the New Zealand and Australian governments, under which a common set of supervisory standards would be applied (at least to the big banks operating in both countries), and the two countries would agree in advance on a (binding) formula for the allocation of losses in the event of failure (and bailout). As he notes, roughly 87 per cent of the big-4 assets are in Australia and other places, and 13 per cent are in New Zealand. In this model, New Zealand would commit to 13 per cent of any bailout costs, enabling resolution issues to be handled jointly (by a single agency accountable to both governments/Parliaments). On the European model (ESM), this single agency could even be given the ability to borrow to meet recapitalisation costs. Under this sort of model, Australia would (presumably) get rid of depositor preference, and we would get rid of local incorporation requirements for Australian banks.

One can, sort of, see why something along these lines might, on the right terms, appeal in Australia. There was long been a strand of thinking in Australia that we are (a) free-riders, and (b) more than a little crazy. In other words, so the argument goes, the soundness of our banks mostly depends on robust APRA supervision at the group level (“after all, the RBNZ doesn’t do any ‘real’ supervision at all”). And, as for OBR, well “you can’t really be serious, can you……..? We hope not…………” So from an Australian perspective, arrangements that tied us into a pre-commitment to share the cost of bailouts would be a win – a (pretty modest) fiscal saving, but removing the uncertainty that perhaps the crazy New Zealanders might actually use OBR and thus (in some thinking) further damage the wider banking group.

But on what terms would it be attractive to Australia? Presumably terms on which the Australian authorities got to determine, finally, what banking regulatory standards were applied, and what action would be taken at the point of (actual or impending) failure. New Zealand might be represented on a regulatory agency board, but with 13 per cent of the financial contribution, it might perhaps get 13 per cent of the vote. 13 per cent of the vote on a two-country entity is no power at all.

When I asked him, Schoenmaker suggested that perhaps the arrangement would have to be one in which New Zealand had a veto. If so, it would rather dramatically change the nature of the arrangement – more attractive to New Zealand, but (almost surely) totally unacceptable to Australia. Is it even possible to conceive of an arrangement under which an Australian government would commit, by treaty, to giving New Zealand a veto on (a) bank supervisory policies, and (b) crisis resolution? I wouldn’t if I was them.

And even if, somehow, such an arrangement were put in place in a mutual fit of bonhomie and trans-Tasman togetherness, there is no certainty that it would be honoured in a crisis (perhaps by then under different – more mutually distrustful politicians). This was the big point on which Schoenmaker and I differed at his seminar. I argued that if, say, New Zealand wanted to let the bank fail and Australian wanted to bail them out then whatever the treaty said, Australia could – and probably would – just do so anyway. Sure, there might be a binding treaty with dispute resolution provisions, but they would take years to get to a determination (think of the WTO disputes) and the crisis needs dealing with tonight. Schoenmaker argues that it just doesn’t happen, but (a) we don’t have examples in banking crisis resolution, and (b) his mental model is one of the EU where there are (i) lots more countries, not just one big one and one small one, and (ii) a shared elite commitment to working towards political union. There is nothing similar here.

Perhaps the Australians wouldn’t renege, but we’d have to take account of the possibility. And with all the banks based there, not here, the issues and risks aren’t remotely symmetrical. If, one day, New Zealand and Australia are working towards a political union, something along the lines of what Schoenmaker suggests might well be one part of that progress. For now, it isn’t an idea that is likely to go anywhere, and nor should it go much beyond the seminar room (and any associated public debate).

If it doesn’t happen, Schoenmaker warns that we may well find ourselves on a path that will eventually make the Australian parents reconsider the benefits of operating in New Zealand at all. As he notes, in eastern Europe many countries are putting up higher and higher barriers (eg very high capital requirements) to assure themselves of an ability to manage foreign-owned subsidiaries of western banks in a crisis. If it were to come to that point in New Zealand, I personally think it would be unfortunate (we gain from having at least modestly-diversified banks), but it isn’t clear that New Zealand voters would necessarily see it the same way. And if the two countries really wanted to deal with the potential costs of high New Zealand local capital requirements, they (Australia) could at last do something about mutual recognition of trans-Tasman imputation credits. The inability/unwillingness to resolve that issue after 30 years is a salutary reminder of why we should not count on being able to easily pre-specify rules for handling a major economic and financial crisis hitting the two countries. Crises, and loss allocations in particular, are almost inherently nationa, and – for now anyway – these two nations aren’t merging.

(And, of course, the politics of banking in the two countries remains quite different. We weren’t the country that almost nationalised the banks in the 1940s, and – whatever the unease in some quarters now about Australian domination of the banking system – we aren’t the country where the possibility of a Royal Commision into banking – to what possible substantive end – is in the headlines day after day.)

(There was an attempt by the Australians to take over all supervision back when Michael Cullen was Minister of Finance. Alan Bollard – rightly in my view – fought back strongly and eventually persuaded the government not to accede to the Australian government bid. Much of the reason for resistance comes down to the ability to manage crises in the interests of New Zealanders.)

What do you think of the Reserve Bank’s revised bank outsourcing policy? It mainly seems to be motivated by concerns that an Australian government will use the threat of switching off the NZ sub to pressure the NZ government to do things it would rather not do in a crisis (like bail out the sub). It’s a very costly policy given that there are large economies of scale to bank IT systems, and the risk it addresses is remote. And the Australian government has various other means of exerting influence over New Zealand. But it is conceivable that an unfriendly Aus govt would act as the RBNZ fears. I’m not sure if it’s worth the cost though. What do you think?

LikeLike

I haven’t read it (but will try to do so). Personally, my bias is now towards rethinking the outsourcing policy (towards something more liberal), partly because i think the domestic political pressure to bail will be overwhelming if any of the big banks fail, no matter what the Aus-pressure situation.

LikeLike

But who pays those restructuring costs? NZ consumers or bank shareholders?

LikeLike

Very hard for a layman to understand but I will reread. From my perspective bank failure is a black swan event. I entered ‘NZ disaster preparedness’ into google and it returned a page of answers that covered earthquakes with a side order of volcanoes. Pleased the RBNZ and informed commentators discuss these matters.

LikeLike

Sorry about the relative obscurity. In many respects, central banks (at least with a financial stability hat on) are like the crash fire brigade at the airport: all exercising and preparation for really bad events they hope never actually to experience.

LikeLike

As a thought experiment compare a sudden volcano in my back garden to my Bank abruptly failing. The former: well I’d fill up the car and drive away; the latter: well petrol station doesn’t accept my card and I’m using the same plastic source to buy my granddaughter’s nappies and some cooking oil – result disaster.

Nobody in the UK had considered a retail bank could fail until customers began to queue to remove their deposits from Northern Rock. I was a world away and it had never been my bank but it still makes me shudder to contemplate it.

What I deduce from your article is that if things went wrong then Australia could if it wished choose to be the big bully but NZ couldn’t. A permanent problem related to relative size that presumably applies wider than banking. So a small country either attempts to dissolve itself into the big country (e.g. join the EU) or keep itself independent (Brexit) but trying to find a middle ground means being at a disadvantage or at least being dependent on good-will.

LikeLike

Australia has shown a willingness to protect its banks from collapsing. They would more than likely force a NZ taxpayer bailout to assist in ensuring that the NZ subsidiary banks do not collapse either which is not necessarily a bad thing.

If the worlds Central Bankers did not decide to act in unison during the GFC around the world our own hawkish RB governor at the time would have still have maintained the OCR at the high end of 9% until today. Wheeler also did initially demonstrate a keen willingness to push upwards interest rates being the very first bank in the entire world to be pushing up interest rates when globally everyone was still pushing interest rates down before realising that he had completely misjudged.

LikeLike

….hmm; think there needs to be a shift in mindset within bankers-regulators-capital investors re public money being the ultimate backstop to ‘the system’; it is almost as if bank resolution via bail in is somehow beyond the wit of man; if there is still ‘too little’ capital relative to risk, NZ should increase the former at the local entity and if the Australian banks can’t generate high double digit ROEs, I’m sure there will be plenty of domestic equity investors willing to accept low double digit ROEs….

LikeLike

Raising capital does not reduce the risk as Capital is only a historical book entry and really has no significance to risk mitigation. It is how that capital is used that mitigates risk.

Cr Capital

Dr Cash in the bank

Cash in the bank is then on lent. The risk management comes from where that cash gets lent or invested to earn a margin. The entries are,

Cr Cash in bank

Dr Investments or

Dr Lending to borrowers

Thats where economists fail to deliver the correct outcomes. They do not know how to read a a set of Financial Statements.

LikeLike

Tax payer bank bailouts are the most distasteful in my book. But somehow we bank or every financial institution in this country. I suppose high return on political donations, or high leverage….

LikeLike

Bank or =>bail out

LikeLike

In a NZ context, where the banks are primarily retail, I think the compelling pressure to bail wouldn’t come from big donors, but from the sheer mass of retail depositors and their families. A bank like ANZ could easily have half the country (or more) as either direct depositors or immediate family of direct depositors.

Which is part of the reason why I favour deposit insurance as a (second best) way of scratching that itch – which won’t go away – will still allowing losses to be imposed on wholesale creditors.

LikeLike

1) Schoenmaker’s model is more appropriate for the EU with a degree of political union.

2) The Herfindahl Index (H) for the NZ banking market is between 0.15 to 0.25 indicating moderate concentration (we roughly have 0.25^2 *4 = 0.25 ignoring kiwibank). We need more competition & there is probably an argument that the current big 4 banks verge on still being systemically too large a risk for NZ and the capital ratios should be conservatively managed. Local incorporation was obviously a good step towards risk reduction.

3) I’ll make the point again that not having a deposit insurance system is absurd. We can insure just about everything else, house, car etc. Having one would also better align NZ & Australian regulations without going as far as 1).

LikeLike

Agree re deposit insurance (altho note that there is nothing in law prohibiting private deposit insurance, altho the probablility of unpriced govt bailouts probably squeeze out any effective demand for such insurance). Private insurance probably couldn’t cope with systemic risk in a big country, but in a small country, with scope for offshore reinsurance, it could – in principle – cover most risk.

LikeLike

Good to see some public discussion from somebody who has worked for the Reserve Bank.

I am interested in why do you think Schoenmaker’s model is appropriate at all when it takes no account of the currency sovereignty status of the countries involved?

While I agree totally NZ should have a deposit guarantee scheme I would have thought that one of the main advantages to this would be that it can be effectively implemented by the reserve bank and would therefore have no need to impact on our government budget in the event it needs to be invoked (which has a lot to do with currency sovereignty of course). Another advantage being that the rules of the bailout can be agreed well before, rather than in a rush behind closed doors and probably with little public oversight.

LikeLike

I didn’t agree with the usefulness of his empirical model (ie how large losses states can cope with), and the real focus of the post was on the idea of a trans-Tasman banking union (and ideas of that sort have appeared here from time to time).

Re your second para, remember that any expenditure by the RB is consolidated into the overall government budget, and that there is an important distinction betweeen deposit insurance and bailouts. Deposit insurance allows some things to be pre-specified, and it should help reduce the chances of a general bailout, but it won’t reduce that probability to zero, and if a bailout happens it is still likely to be a rather rushed thing, done with little ex ante oversight (as happened for example with the deposit guarantees in 2008 – issued under MOF powers in the Public Finance Act requiring no parliamentary approval or appropriation).

LikeLike