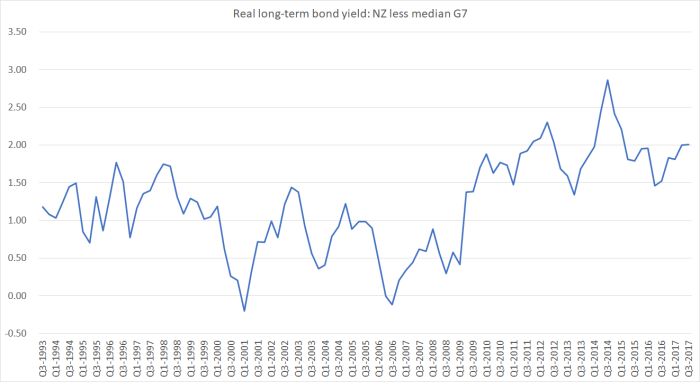

In Friday’s post, I illustrated how persistent and large the gap between New Zealand long-term interest rates and those in other advanced countries has been (and remains). The summary chart was this one

The gap is large and persistent whichever summary measure of other countries’ interest rates one looks at.

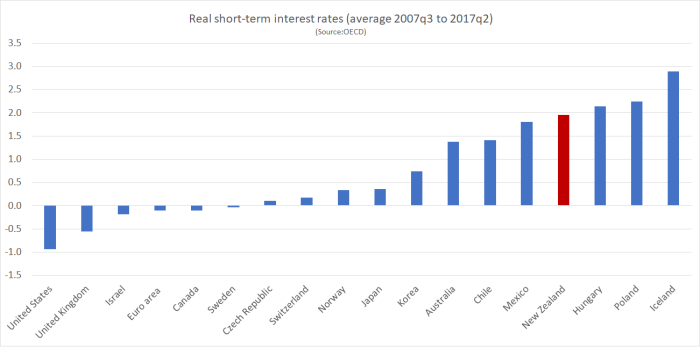

It is also there for short-term interest rates. In this chart, I’ve shown average real short-term interest rates for the OECD monetary areas (17 countries with their own monetary policies, plus the euro-area) for the last 10 years, adjusting average nominal interest rates for average core inflation (the OECD reported measure of CPI inflation ex food and energy).

Of the countries to the right of the chart, Iceland and Hungary have had full-blown IMF crisis programmes in the last decade, and Mexico and Poland had precautionary programmes. That isn’t meant to suggest that New Zealand is crisis-prone, just to highlight how anomalous our interest rates look relative to those of the other more-established advanced economies.

In yesterday’s post I reviewed some of the arguments sometimes advanced to explain why New Zealand interest rates have been persistently higher than those in other advanced countries. As I noted, these factors don’t look like a material, or compelling, part of the story:

- size (of the country),

- (lack of) economic diversification

- market liquidity,

- creditworthiness,

- accumulated external indebtedness,

- unusually rapid productivity growth

And, as I noted, none of those explanations has as a corollary a persistently strong real exchange rate. A story that can make sense of New Zealand’s persistently high real interest rates needs to be able to make sense of the persistently strong exchange rate, and also of New Zealand’s persistently poor productivity performance. As it is, in a country with a poor productivity performance and the disadvantages of remoteness, one might have expected to find persistently low interest rates and a persistently rather weak exchange rate.

At an economywide level, interest rates are about balancing the availability of resources with the calls on those resources. In principle, they have almost nothing to do with central banks – we had interest rates millennia before we had central banks. They also don’t have anything necesssarily to do with “money”, except to the extent that money represents claims on real resources.

In any economy with lots of exceptionally attractive and profitable opportunities, firms will be wanting to do a lot of investment. Resources used for investment today might well generate really strong returns in the future, but those resources can’t also be used for consumption (or producing consumption goods) today. Interest rates play the role prices typically do – acting as “rationing device”. Higher interest rates today make some people willing to consume a bit less now, and they also help ensure that the only the investment projects with the higher expected returns go ahead. In other words, interest rates help reconcile savings and investment plans. (If they couldn’t adjust that way, the price level would do the adjustment – and that is where central banks these days come in, adjusting the actual short-term interest rate to reconcile savings and investment plans while keeping inflation in check).

Sometimes the strong desire to undertake investment projects will be based on genuinely great new technologies. Sometimes it might be just based on a pipe-dream (credit-fuelled commercial property development booms are often like that). Sometimes, it will be based on direct government interventions (one could think of the Think Bg energy projects). And sometimes, it will simply be based on rapid population growth – people in advanced economies need lots of investment (houses, roads, shops, offices, schools etc).

Various factors can influence the desire to save. If firms in your country have developed genuinely great new technologies, it may seem reasonable to expect the future incomes will be a lot higher than those today. If so, it might be quite rational to spend heavily now in anticipation of those income gains (consumption-smoothing). Some governments tend towards the spendthrift, and others towards the cautious end of the spectrum. Tax and welfare rules might affect desire and willingness to save (although my reading of the evidence is that they affect more the vehicles through which people choose to save). Demographics matter, and compulsion may also play a part. Culture probably matters, although economists are often hesitant about relying on it as an explanation. Business saving is often forgotten in these discussions, but can be a significant part of total savings.

But if, for whatever reason, people, firms and governments don’t have a strong desire/willingness to save at “the world interest rate”, then (all else equal) interest rates in your country will tend to be a bit higher than those in other countries. And if firms, households and governments have a strong desire to invest (building capital assets) at “the world interest rate”, then (all else equal) interest rates in your country will also tend to be a bit higher than those in other countries. Quite how much higher might well depend on how interest-sensitive that investment spending is (in aggregate).

Of course, we don’t get to observe actual supply curves for savings, or demand curves for investment. We don’t know how much New Zealanders (or people in other countries) would choose to save or invest at “the world interest rate”. Instead, we have to reason from what we do see – actual investment (and its components) and actual savings.

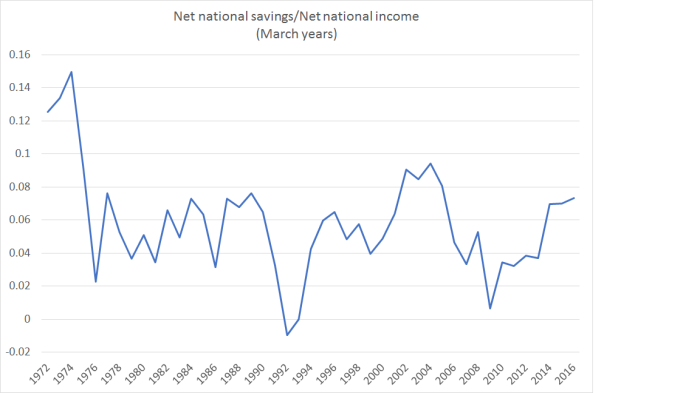

Take savings rate first (and by “savings” here I mean national accounts measure – in effect, the share of current income not consumed). Net national savings rates in New Zealand have been similar, over the decades, to the median for the other (culturally similar) Anglo countries, but lower typically than in advanced (OECD) countries more generally. Savings rates are somewhat cyclical, but as this chart illustrates, for some decades now they’ve cycled around a fairly stable mean (through big changes in eg tax policy, retirement income policy, fiscal policy, financial liberalisation etc).

All else equal, if tomorrow we woke up and found that somehow New Zealanders had a much stronger desire to save then our interest rates would fall relative to those in the rest of the world. But that is an illustrative thought-experiment only, not a basis for direct policy interventions. A relatively low but stable trend savings rate over a long period of time – especially against a backdrop of moderate government debt – suggests something more akin to a established feature of New Zealand that policy advisers need to take account of. A different New Zealand economy might well feature a higher national savings rate – more successful firms, wanting to invest more heavily over time to pursue great profit opportunities, retaining more profits to reinvest – but that would be an outcome of a transformed economic environment, not an input governments could or should directly engineer. Higher saving rates are not, automatically, in and of themselves, “a good thing”.

By the same token, if we all woke tomorrow and (collectively) wanted to build less physical capital (“invest less” in national accounts terminoloy), our interest rates would fall relative to those in the rest of the world. Actually, that is roughly what happens in a recession: pressure on scarce resources eases and so do interest rates (central banks typically helping the process along). But less (desired) investment is not, in and of itself, “a good thing”. Nor, for that matter, is more investment automatically desirable – in the last 40 years, investment/GDP was at its highest in the Think Big construction phase.

Whether over the last 40 years, or just over the last decade, investment/GDP in New Zealand has been very close to that of the typical advanced country. On IMF data, investment/GDP for 2007 to 2016 averaged 22.0 per cent in New Zealand, and the median advanced country had investment as a share of GDP of 22.1 per cent.

But these investment shares for New Zealand happened with (real) interest rates so much higher than those in the rest of the world. As I noted earlier, we can’t directly observe how much investment firms, households and governments would want to have undertaken at the “world” real interest rate – perhaps 150 basis points lower than we actually had.

We might, however, reasonably assume that desired investment would have been quite a bit higher than actual investment. Both because some investment – whether by firms, households or (more weakly) government – is interest rate sensitive, and because we’ve had much more rapid population growth than the typical advanced economy. In the last 10 years, the median advanced country has had 6 per cent population growth, and we’ve had 13 per cent growth in population. More people need more houses, shops, offices, road, machines, factories, schools etc. All else equal, with that much faster population growth we’d have expected more investment here (as a share of current output) than in the typical advanced economy. But all else isn’t equal, because our interest rates are so much higher. That population-driven additional demand is one of the reasons why interest rates have been so much higher than those abroad. Combine it with a modest desired savings rate, and you have pretty much the whole story.

As I noted earlier, some investment is more readily deterred by higher interest rates than others (“more interest-elastic” in the jargon). Most of government capital expenditure isn’t – government capex disciplines are pretty weak, and if (say) there are more kids, there will, soon enough, be more schools. And more people will mean more roads. A lot of household investment isn’t very interest-sensitive either: everyone needs a roof over their head and (by and large) they get it. With a higher population growth rate than other countries, on average we devote a larger share of real resources to building houses than other advanced countries typically do (albeit less than might occur with well-functioning land markets). Business investment is another matter altogether. Businesses only invest if they expect to make a dollar (after cost of capital) from doing so. All else equal, increase the interest rate and less investment will occur. That won’t apply to all sectors, because in the domestically-oriented bits of the economy not only are interest rates higher, but the underlying demand is higher (more people). And so non-tradables sector investment probably isn’t very materially affected. But for the bits of the economy exposed to international competition (whether exporting, competing with imports, or supplying firms that do one of those) it is a quite different story. An increased population here doesn’t materially increased demand, and a higher cost of capital makes it harder to justify investment in the sector.

And all that is before even mentioning the exchange rate.

In an open economy, the floating exchange rate system is what allows countries to have different (risk-adjusted) nominal interest rates. Without a floating exchange rate, higher interest rates here would offer a “free lunch”, and the interest rate differences wouldn’t last. With a floating exchange rate, one can have differences in interest rates across countries, but the exchange rate adjusts such that, overall, expected returns are more or less equal across markets. Higher interest rates here are, roughly speaking, offset by an implicit expectation that one day our exchange rate will fall quite a lot. It appreciates upfront, to create room for that future depreciation.

The exchange rate, of course, also serves as a “rationing device”. Some of the high domestic demand spills over into imports. And the higher exchange rate makes exporting less profitable, all else equal. And so when we have domestic pressures (savings/investment imbalances at “world” interest rates) that put upward pressure on our interest rates, not only is business investment in general squeezed, but the squeeze falls particularly on potential investment in the tradables sector. Firms in (or servicing) that sector face a double-whammy: a higher cost of capital, from the higher real New Zealand interest rates, and lower expected revenues as a result of the higher exchange rate.

We don’t have good data on investment broken down between tradables and non-tradables sectors. But we do know that overall business investment as a share of GDP has been towards the lower quartile among OECD countries (whether one looks back one, two, three or four decades), even though we’ve had faster population growth than most. We also know that there has been no growth at all in tradables sector real per capita GDP since around 2000, and we know that the export share of GDP has been flat for decades (even though in successful economies it tends to be rising). Those stylised facts are strongly suggestive of a situation in which:

- lots of government investment takes place (market disciplines are weak),

- lots of houses get built (even if not enough – because people need a roof over their heads),

- a fair amount of investment occurs in the non-tradables sectors, despite the high interest rates, but

- a great deal of potential investment in the tradables (and tradables servicing) sectors has been squeezed out.

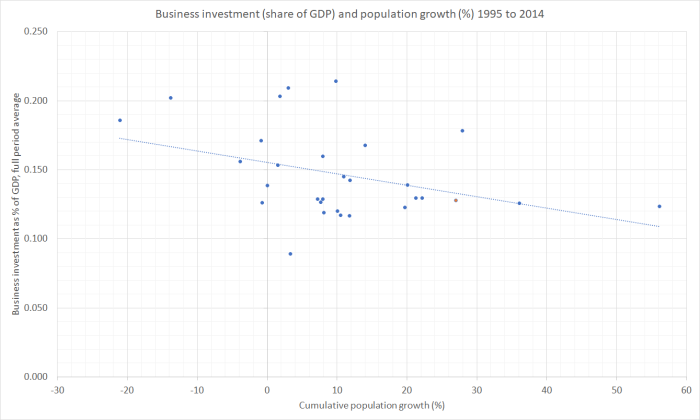

That is, roughly speaking, how we end up with rapid population growth and yet an investment share of GDP that is no different from that of a median advanced economy. We know that population growth seems to adversely affect total business investment across the OECD (I ran this chart a few months ago)

And it is surely only commonsense to reason that tradables sector investment will have borne a lot more of the brunt than the non-tradables sectors.

I’m not getting into the details of immigration policy in this post. Suffice to say that our immigration policy – the number of non-citizens we allow to settle here – is the single thing that has given New Zealand a population growth rate faster than that of the median OECD/advanced country in the last 25 years or so. It is, solely, a policy choice. Our birth rate is a little higher than that of the median advanced country, but we have a large trend/average outflow of New Zealanders. So, on average, the choices of individual New Zealanders would have resulted in a below-average population growth rate (again, on average over several decades). And that, in turn, would seem likely to have delivered us rather low real interest rates and a lower real exchange rate. Real resources would have been less needed simply to meet the physical needs of a rising population, and more firms in the tradables sectors would have been able to have overcome the disadvantages of distance. And our productivity outcomes – and material living standards – would, as a result, almost certainly have been better.

You can read about all this at greater length in a paper I did for a Reserve Bank and Treasury forum on the exchange rate and related issues back in 2013.

High interest rates caused by high population growth. What about NZ just being arisky country? Earthquakes, vocanoes, tidal waves and an economy that would be thrashed by an outbreak of foot and mouth.

I remember high interest rates in PNG ; surely a rusky country and little to do with a birth rate that really is high.

LikeLike

all possibilities, but there is no external evidence for them (eg no evidence that NZ-based borrowers borrowing in USD terms pay more – higher interest rates – than other advanced country borrowers).

And unlike many other countries, we don’t face much risk of invasion, or limited nuclear attack, or EU-breakup risk or…….

A “population growth interacting with modest savings rates” story is an entirely conventional sort of macro story.

As for PNG, the underlying degree of credit risk is hugely higher. I still recall the story the head of PNG ANZ told me about the time they had to send someone out to a village to retrieve a fridge that had secured a personal loan. Was (physically) risky for the banker……

(Comparisons across stages of development shed light on some things, but it is usually more enlightening in understanding oddities in an advanced country by comparing across other advanced countries).

LikeLike

It is particularly significant for New Zealand that the higher interest rates that we pay are mostly paid to foreign-owned banks

LikeLiked by 1 person

Of course, most of the high interest rates are paid by NZers too other NZers (both our lending and deposit rates are high, and bank profits aren’t much affecrted by the absolute level of interest rates). On the net IIP position we are paying foreigners – ultinately savers in other countries.

LikeLike

Maybe population growth needs explication. House building and need for cars etc relate to family units rather than individuals. So stopping family reunion which mainly meant bringing isolated grandparents to live in the same house will have had little effect whereas a move to younger single immigrants will be making matters worse.

LikeLike

This post isn’t about the detail recommendations for immigration policy, but the distinction you draw isn’t quite so clear cut: the young single people will often be working (ie adding to available capacity) and might well be flatting, those using houses just as intensively as an extended family including an elderly grandparent.

LikeLike

seems the ‘flow of saving’ from the household sector is low because the ‘savings stock’ is perceived as permanently high given elevated house prices; that’s the square I can’t circle – what happens if the stock of savings turns out to be lower than currently perceived? I guess the flow of saving could increase which could lead to the lower current demand and fall in interest rates / exchange rate; the trigger? no idea but if housing supply meets policy expectation, could be part of the reassessment….a big if…

LikeLike

you might be right about an interaction with perceived housing wealth, but……not that the flow savings rate hasn’t fallen since house prices started rising strongly. the key thing about a lot of housing “wealth” is that the flipside of that “wealth” is the higher expected cost facing younger generations. The country as a whole isn’t better off, even if a few individuals/families are.

LikeLike

…..yes but it isn’t always domestic residents that are settling housing or other real / financial asset transactions; I’m not sure how it fits in but the BIS (promoted by earlier post) argues best to keep any eye on gross as well as net capital flows given growth in the former over the past few decades; another confusing area on the fx dilemma….for my mind at least!

LikeLike

in terms of financial risks, I think grosses certainly matter at least as much as nets. You could, in a sense, see that in the US/euro area positions pre-crisis. Net they weren’t that big (apparently) but there were some very large gross positions, that were part of what gave rise to elements of the crisis.

LikeLike

This is the only coherent macro level explanation of the long-term underperformance of the economy that I have seen. I hope they teach it in Econ 101.

I guess my quibble would be with treating the low savings rate, on the one hand, as a fact of nature, and the high immigration rate as a policy choice. (Fully acknowledging that the former would take a lot of political capital to change, and the latter could be changed in a week with very little blowback from voters, if not donors).

My reading of history is that there has been a very deliberate series of decisions since the 1930s to obviate the need for precautionary private saving, from the development of the welfare state to the rise of national super to the deregulation of consumer credit. It’s my further view that capitalism doesn’t really “work” without a large pool of private savings, although it’s better than socialism without savings.

This would explain why even in years when immigration has been very low, there hasn’t been a big turnaround in the economy. Of course you need at least 3 years to see a chance in trend. It looks like manufacturing is just beginning to pick up in the UK after years of a lower exchange rate.

LikeLike

Re savings, I entirely take your point in absolute terms, but there isn’t much evidence that policy changes in those areas have, in overall effect, been much different than in the rest of the advanced world. As we’ve discussed previously, even in Australia national savings rate didn’t rise after compulsory super came in (altho of course the Aus national savings rate is materially higher than in the rest of the Anglo world, probably largely because production structures – esp the mining sector – are very capital intensive (hence high business saving).

Re your immigration point, two points. First, when our interest rates got down to US levels in 2000 the exch rate did go very low and in time we started seeing quite a volume response…..and then the exch rate rose sharply again. At the time, of course, there was a lot of uncertainty about how temporary the fall would be – I recall Don Brash being v optimistic it was permanent, while most of the senior RB staff were much more sceptical. The other point is that when net migration falls sharply it is usually associated with “other stuff” going on – there haven’t been any clean substantial policy changes in the last few decades that one could point to for a test of what an exogenous adjustment might lead to. The last big discrete changes were in the early 90s when we were still adjusting to all the other big reforms.

Which is frustrating all round, since it makes it hard to “prove” my case, and hard to refute it – in fact hard to test statistically at all, which I why I rely – as economic historians often do – on narrative, reasoned argument, identifying corollaries etc.

On Tue, Nov 7, 2017 at 3:59 PM, croaking cassandra wrote:

>

LikeLike

I’m sure the tax wedge doesn’t help either.

Paying tax on, say, term deposits probably implies the real rate has to be pushed up to some degree to compensate.

LikeLike

Very interesting. Are you able to point to anything that indicates reducing population growth by your suggested 40,000 people per year (around 1% of the population) would have enough of a quantitative impact on non-tradable investment demand to see interest rates converge to the OECD median? You’ve mentioned before that the capital stock is 2.5-3 times GDP. Assuming most of this is non-tradable, this would suggest that a reduction in population growth equal to 1% of the population would reduce non-tradable investment demand by about 2% of GDP. This seems like a relatively small amount. But would the elasticity be high enough to see interest rates drop by the 100-200bp needed to converge to the OECD? Also, would this even be a good thing given NZ’s current proximity to the zero lower bound?

LikeLike

Interesting question, which I will reflect further on. For now, it does seem plausible: the effect of cutting annual population growth by that much would be similar in effect to, say, a 2 percentage point reduction in excess demand (at world interest rates) – the change in investment offset by a smaller change in savings. Shift the output gap by that much and my impression would be that interest rates would move by perhaps a couple of hundred basis points. It isn’t an exact parallel, but is conceptually similar, and involves removing that incipient excess demand (again, at world interest rates) each and every year.

I’m not sure the immigration policy change alone would lead to full interest rate convergence (the int rate gap is , after all, a reflection of two sides of the coin – savings supply and investment demand), but I am confident of the direction of the effect, and that the scale of the effect would be substantial (not just in the initial transition but semi-permanently). And the implications for the exchange rate even if the average gap was only halved would be pretty substantial.

LikeLike

If I understand correctly, I think what Zathras is saying is the bit I can’t get my head around. In my words, would current immigration levels increase our interest rates by 100-200bp, or some chunk thereof? It doesn’t seem likely to me, so I look forward to some further thoughts on this.

LikeLike

Actually, it is totally consistent with past RB research that immigration shocks generate pretty substantial interest rate effects. In this paper https://www.rbnz.govt.nz/-/media/ReserveBank/Files/Publications/Analytical%20notes/2013/an2013-10.pdf a 1% shock to population from immigration boost 2 year fixed mortgage rates by 0.5 percentage points (the effect on the OCR or 90 day rates – not modelled – would be larger). Recall that one of the problems in thinking about this issue is that we don’t observe actual exogenous immigration shocks (because migration policy is pretty stable). Thus the reduced exodus of NZers to Australia in recent years goes hand in hand with (is causally related to) relatively weak domestic demand and activity in the economy of our largest trading partner. Thus, in the data we observe, immigration effects are offset by eg trade and investment effects.

LikeLike

I was thinking about this today and came across a couple of estimates that broadly support your hypothesis:

1. In the RBNZ’s May MPS, they have a ‘higher output gap scenario’ where they estimate that a 0.8ppt higher output gap would require the OCR to be 40bp higher. Based on this, a 1ppt lower population growth rate, leading to investment demand 2ppt of GDP lower, would translate to 100bp lower interest rates. That would partially, but not fully, close the gap to world interest rates.

2. There is a theory that the neutral interest rate should be equal to the potential growth rate. 1% lower population growth would then translate to 100bp lower interest rates. I’m not sure how robust that theory is though.

LikeLike

Thanks. My impression – which i may have wrong – was that NZSIM was calibrated to something more like 100bps for a 1 percentage point change in the output gap. Of those two May 17 scenarios, in some ways the residential investment one may be more useful – because it is about a forecast difference (whereas the output gap one was about realising they’d been wrong for the last couple of years). In the res I scenario, a half percent of GDP decrease (in the policy relevant window) lowers the OCR by around 0.5 percentage points.

Thanks for the reminder of point 2, which I should have cited myself. I wouldn’t put much weight on the precise relationship – esp as we have long been in a non-equilibrium situation – but it is another straw in the wind supporting the idea that an exogenous change to population growth will make quite a difference to the future path of interest rates.

While it certainly isn’t conclusive I’d cite the experience in the laste 70s and early 80s, when net migration moved structurally lower, is not inconsistent with my story. Interest rates were too regulated to make much of, but the real exchange rate was certainly trending lower.

LikeLike

…part of the same investigation? a real brain ache now…(!!):

http://www.treasury.govt.nz/publications/research-policy/wp/2010/10-09

LikeLike

yes, I was quite involved in that paper (working at Treasury at the time).

LikeLike

I would say mining, drought, super, means testing of age pension, lack of ACC, and greater financial literacy all contribute to the higher savings rate, among other things.

LikeLike

Means-testing of the age pension quite probably works in the opposite direction (discouraging middle class savings while making no difference to people at the top, or the bottom.)

I’m sceptical that ACC makes much difference, esp since under the prevous govt it became a funded scheme.

I’m not wedded to these explanations individually, but it is worth remembering that Australia’s national savings rate was materially higher than NZ’s (or those of other Anglo countries) 40 or 50 years ago too.

LikeLike