I was going to write about something quite different this morning but I noticed an article by Bernard Hickey suggesting that the presence of a capital gains tax in Australia, and tighter restrictions there on foreign ownership of residential property, explains a substantial difference in performance in the two housing markets, across decades and over the last few years in particular.

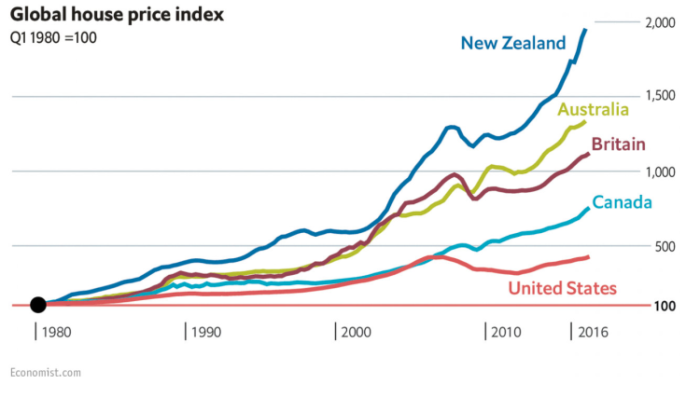

Hickey starts from this chart, using a helpful tool The Economist makes available for comparing house price inflation across countries.

But (a) this is a chart of nominal house prices and everyone knows we had much more general inflation than these countries early in the period, and (b) 1980 marked near the trough of a savage correction in New Zealand real house prices (down around 40 per cent over five years or so, as the New Zealand economy went through some troubled times and the exodus of New Zealanders to Australia (not then offset by increases in other immigration) began). 1980 is the starting point The Economist uses, but it isn’t where I’d be starting looking for evidence of the contribution of Australia’s CGT and foreign ownership restrictions.

Australia’s capital gains tax came into effect in September 1985. The restriction on foreign ownership of residential properties was already in place, but no one thinks that was a material issue in Australia at the time (either there, or here). Rising concerns about non-resident foreign ownership (actual or potential) of residential dwellings – especially in New Zealand – have mostly been an issue for the last five years.

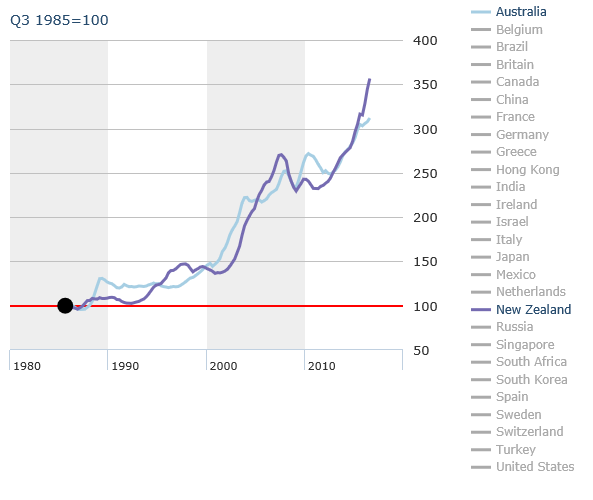

So how have real house prices in the two countries behaved since September 1985, when Australia introduced the CGT? Using the same Economist database – which has data only up to the end of 2016 – this is the resulting picture.

In total, real house prices have increased a little more here than in Australia. But at times, even over this period, prices in Australia have been increasing faster and at times here. In the late 80s for example – just after the capital gains tax was put in place – prices in Australia were much stronger (the difference is quite large even if, without a log scale, it doesn’t appear that way). And real house prices here fell from around 1997 to 2002 while they surged in Australia.

There are, of course, differences in the housing markets in the two countries, but the similarities look a lot stronger than the differences. Both countries have tight land use restrictions, both countries have had rapid population growth (and although both countries currently have quite low absolute interest rates, both countries have among the highest real interest rates anywhere in the advanced world). Here is the last 20 years of data (1996 q4 to 2016 q4).

Over the whole period, New Zealand house prices have increased just slightly less than those in Australia.

Of course, over just the last few years New Zealand real house prices have increased more than those in Australia. Capital gains tax provisions haven’t changed materially in the two countries, although we did impose the bright-line provisions (on re-sale within two years) in 2015, and Hickey notes that Australia “removed the exemption from its capital gains tax for the main home for overseas investors in this year’s budget” (beyond the end of the data in these charts).

Perhaps the differing approaches to non-resident non-citizen purchases of existing residential property have played a part, at the margin. We’d need a much more careful study to know, and it may never be possible to conclusively answer the question. But recall – the point I made yesterday – that banning, or taxing, non-resident purchases of existing dwellings does not stop such purchasers buying new properties, or does not remove any of the road-blocks that stand in way of increased supply, of urban land in particular. In both countries, land price inflation is by far the largest component of urban house+land inflation.

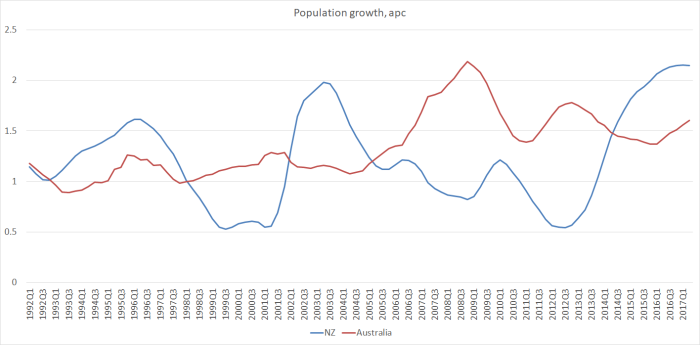

Personally, I’ve got a different candidate explanation for why house price inflation has been stronger in New Zealand just in the last few years than it was in Australia: our population growth has simply been much faster.

Those are huge swings – both in New Zealand’s own population growth rate, and in that growth rate relative to Australia’s population growth rate. You might think that rapid population growth is a fine thing – as people at the New Zealand Initiative (probably) do – or a deeply problematic one, as I do, but no serious observer is going to dispute that when you have the sorts of land-use restrictions that both New Zealand and Australia do, big unexpected changes in population growth will, all else equal, quickly spill into higher house prices. They did in Australia around the post-recession peak mining investment boom years, and they’ve done so here in the last few years. Over longer periods of time, the two housing markets look (depressingly) similarly bad.

To be clear, I’m not suggesting that idiosyncratic tax or (eg) credit-restriction changes have no effect on housing market in the short-term. Australia has tinkered with its CGT, we’ve altered depreciation rules, ring-fencing rules etc, and we’ve put up and lowered again our maximum marginal tax rates (all things potentially relevant for investors). I’m also not suggesting that large enough changes in the foreign buyer rules will have no effect in the short-term. But the New Zealand and Australian experience over decades suggests that such effects don’t last for very long (and any permanent effects are pretty small), that the similarities in the two markets are much more important than the differences, and the toxic brew of tight land use restrictions in the face of policies that drive up the population rapidly are a more compelling part of the story in both countries. Relative economic cycles aren’t always in synch, and waves of intense population growth occur at slightly different times but the divergences in relative housing market performance never seem to have last for very long. And are unlikely to, unless one or other set of governments sets about seriously fixing the land-use rules (and/or materially pull back on the policy contribution to population growth and housing demand).

Even the government seems to agree. Asked about the foreign buyers ban the other day, David Parker noted (according to a record of press conference I saw) that “the impact on the number of houses built in New Zealand will be negligible”, and suggested that any price effect now would be pretty modest too.

The Bright Line Test (another name for CGT forced onto the National government by the RBNZ) was introduced in 2015. Looking at the charts, you could make the same lack of any correlation studies to point to the introduction of the Bright line test as the reason for the increased price spike from 2015 to 2017.

I guess extremely poor researchers like Bernard Hickey and the RBNZ believes that the price of cigarettes actually falls when the tax on cigarettes increase at each budget.

LikeLike

You are funny

Don’t recall cigarettes being sold at auction where price is set by the open market, and then unavoidable excise tax is applied – A tax on tobacco is acknowledged as reducing demand. Remind us how much of the price of a packet of cigarettes is excise tax

LikeLike

Since the tax has pushed the price of cigarettes so high the poor folk who can’t afford it now just beat up Indian shopkeepers and steal it. So I guess you can source these stolen cigarettes from the Dark Web on the various illegal auctions and bid for some stolen cigarettes. So yes it is set in an open auction. All you do is log into one of those Silk Road dark web addresses and go bid. Any tax is a tax. You could just call it a CGT rather than excise tax. same tax just with different names like the Bright Line Tax or you could just call it CGT. Same thing.

LikeLike

When I invested in a lotto ticket yesterday I gave little thought to possible taxation. Somehow whether I gain $20m or $18m doesn’t seem to be much difference. Same with my investment property bought 15 years ago and I thinking of selling – I will make $500,000 and paying 15% CGT will not be life changing. In actual fact the property is owned by my company so one way and another profits will eventually be taxed at my IRD rate.

Therefore CGT at say 15% will have little effect on the market. Foreign buying is too easy to evade so it too will have little effect.

What did bother me about the post was the figures which apparently refer to average or median houses. Both Australia and NZ have a dramatic, rapid move from the country to the city so both countries have bargain price (below cost of replacement) properties in unfavourable small towns and ludicrously expensive property in cities.

The problem of expensive properties is not helped by the various factors that make it difficult for builders of inexpensive housing. That is worth an article on its own and has been mentioned by other contributors recently but my interest is in this drift to the city. These are some factors:

1. Mechanisation of farming – fewer support jobs in small towns

2. Improvement of transport – easier to visit the nearest city for major purchases so fewer support jobs in small towns

3. Tertiary education – most school leavers are forced to move to cities to study and once there build new social networks

4. Sex imbalance – most rural jobs are male dominated: farming, hunting, building infrastructure and when there are no young women the young men will reluctantly follow them to the city. There are many tourist jobs but they tend to be seasonal and therefore held by temporary migrants.

5. Immigration – immigrants like cities; a fact identified by sociologists almost 100 years ago. They may arrive to work in a rural area but they tend to move to the city to mix with fellow immigrants and their children have no extended family ties in the rural areas unlike Kiwis so are faster to move and of course they share a family background in moving to find new opportunities.

6. Modern social media – young people who used to be playing sports or just hanging out are now glued to social media which is an endless advertisement for life in cities.

Many of these factors combine to produce a snowball effect with ever faster decline. Most family wealth in NZ is in property; city dwellers have been winners and owners of rural properties have seen their homes effectively decline in value. Other than lottery winners there is nobody with money to invest locally.

Does it matter? We could just leave it to market forces – that is usually the best answer to distribution of resources but there is a significant social cost with schools, medical centres, libraries and even police stations closing all of which deprive the generally poor rural people who are unable to follow the pied piper to the city of gold. So alarmingly I seem to be agreeing with Winston – we need to do something to slow the decline of our regions.

LikeLike

But it is not market forces which is closing schools, medical centres, libraries or even police stations. That is a government decision. The respective governments labour and National have decided that it is prudent to reduce government foreign debt and to run budget surpluses. When the National government under John Key decided to try and get to a budget surplus in the face of the triple disasters of the GFC, the Christchurch Earthquake and the Kaikoura Earthquake something has to be given up on. There are no free lunches so the saying goes.

My previous opinion at the time was that we could have had a mini QE of $50 billion as a disaster recovery at the time that the US was running its trillion dollar QE. It would have made sense when the USD was declining and the NZD was rising. That would have dropped interest rates and dropped the NZD but it does require a highly competent RBNZ that knew what it was doing and had its eye on global events. Sadly our RBNZ is just a bunch of highly paid people that do not know what they are doing, have not done any research other than to check if there is mould on their cakes that they have for morning tea each day.

LikeLike

Cycled the Otago rail track – at Hyde we staying in units built in the middle of a school rugby field – the school had closed 20 years ago and now the total population of Hyde is 18 with zero children. I was told that where Richie MacCaw grew up there were 5 schools and now there is one. No pupils = no school. That is rapid change. I’m not objecting to the change merely the speed.

I suspect us elderly city folk would move to the countryside if rates were not higher and services less in rural NZ and if retirement villages were being built outside our cities.

Another possibility is to reverse the accommodation benefit which has the government pouring $2b into Auckland so it was higher in rural areas and lower in cities. Given regular free bus passes so the single mothers could make occasional visits to their families and friends in Auckland it would move kids into the countryside which would be healthier for them and it would free up state housing for low paid workers.

Then there is tertiary education – why does it have to be in our cities? The teachers training college used to be in Ardmore when Ardmore was rural. Now it is somewhere in the city. Our government is increasing the student accommodation allowance and providing free tuition which will persuade even more kids to cram into Auckland.

LikeLike

we already have welfare sinks like (my old childhood home) Kawerau. encouraging people to move to those places is a false economy – perhaps some short-term fiscal savings (or city housing on your story) – but at a long-term cost of reducing the chances of those people ever coming off the benefit (and worse, increasing the chances their kids grow up into intergenerational poverty).

Do remember that some rural places are still growing – Ashburton and the dairy areas of Southland will, i imagine, have more people now than they did 40 years ago (whether that is environmentally sustainable is another question).

LikeLike

Welfare sinks: I wasn’t being totally serious, just pointing out one of the many costs caused by the rush to the city and increasing the demand for housing. Whether a welfare sink is in South Auckland or being rebuilt in Northcote or in Kawerau makes little difference to the inhabitants if it is a welfare sink. A suitable small town in a rural area with seasonal work might be better than Auckland; it depends on the numbers involved.

Much more effective to remove the universities from Auckland; a reduction in students would create more low paid jobs suitable for some of our long term beneficiaries. Reduction in immigrants would help too.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What needs to be stated loud and clear is Australia’s CGT never applied to the family home or principal place of residence. Bernard Hickey refers to it indirectly with the tortured statement – Australia “removed the exemption from its capital gains tax for the main home for overseas investors in this year’s budget”

If the bulk of the country’s 9 million homes are family homes then don’t expect any great influence on house price by CGT – it’s a long article to bloviate about something that doesn’t even apply

LikeLike

Indeed (I took it for granted people were aware of that), altho to be fair, advocates of a CGT in NZ also want to exempt the family home. The Aus CGT was also grandfathered.

Advocates of CGT who think it will make a difference to house prices – as distinct from those who just favour it on tax policy grounds – have a view of house prices that sees them substantially driven by “speculators”, independent of structural fundamentals (like land laws, population pressures etc).

LikeLike

TOP makes it a point to include the family home in any CGT regime. I am surprised they even got 2% votes. Clearly they managed to scoop up the students that do not have houses and would like to see the old folk give it up to them.

LikeLike

People are not as self-interested as you believe. I was seriously considering TOP despite their serious attack on my superannuation and a wealth tax on my house. They claimed their arguments were ‘evidence driven’ but I found them argued with clarity, minimal virtue signalling and waffle free (compare with the Greens). Their universal child benefit was a return to a common sense investment in Kiwi children and their immigration policy was clearly designed purely for the benefit of NZ not immigrants.

They lost me with an unnecessary attack on Winston Peters (they couldn’t get it out of their mind that he was racist) when they should have been concentrating on the two main parties and an insistence on what seemed to be an undemocratic Maori veto.

Maybe the majority of voters are self-interested but with a little less Gareth and a reduction in the 5% MMP threshold they had a chance.

LikeLike

Offhand, do you know of any analysis of the impact “speculators” have had on a property market? People prepared to pay a premium because they are fairly certain of large capital gains (regardless of tax) must surely have an effect on price?

LikeLike

I think it is probably an impossible question to answer. A smart person five years ago recognising the wave of immigration to come would have leveraged up, bought property, and sold again to take the profits. But if they hadn’t – if there had been no one like that – the price would eventually have risen anyway, from the underlying population pressure in the face of land restrictions. So-called speculators generally facilitate and speed up price adjustment that would happen anyway, ( but sometimes might overshoot, in either direction).

LikeLike

It would be almost impossible to introduce a CGT in New Zealand – unless it was retrospective – that’s impossible – the inequity would be colossal when it is considered all the gains have been made and many have walked away with those gains while newbies (the young) would wear it – can never do it

LikeLiked by 1 person

The problem was the stupidity of the National Government ever letting the situation to get so out of control – it is now irrepairable – you can put that in your history books for when you look back in 30 years time

LikeLiked by 2 people

Property prices on average have doubled every 10 years if we ignore inflation. From 2007 to 2017 that 10 years concept still holds true. Nothing really to do with the National government.

The property concept is actually very simply but surprisingly for many people and usually those are the economists that do not seem to be able to do maths.

1. 60% to 70% of the property market ie people buying and selling in the property the market are people that already own property. Therefore this concept of affordability is not a factor. They are buying and selling in the same market. Price is not a factor. Affordability is not a factor. 70% of the market does not really care.

2. Therefore it is only 30% of the market needs to have sufficient liquidity to give enough momentum for the 70% to start to buy and sell between themselves.

Where does the liquidity come from to enable this 30% to start to drive the market.

Foreign buyers like Kiwis that buy property with an overseas income with a plan to return to NZ or foreigners who have sold their UK houses and have decided to buy one in Auckland. As we all know London houses or New York houses can cost upwards of $40 million. A equivalent $3 million house in prime Auckland is considered cheap buying.

Now a Foreign buyer could have paid $5 million for the $3 million property and still would consider that cheap but given that property prices are increasingly very transparent and available online at a seconds notice, no one pays $5 million for a $3 million property. But there is an emotional component to any purchase. I really like that property. I won’t pay $5 million because i know the market price but i would be prepared to pay 10% more say $3.3 million. small 10% increases from emotional buying doubles your property price every 10 years. The more emotional the faster the price goes up.

So Jacinda Ardern trys to stop foreign buyers. Fair enough.

But property liquidity also comes from salary and wages which is $180 billion plus the spending by International students and Tourists that spend $15 billion in the economy. The question now is how long does that $180 billion in wages plus that $15 billion spend up by International students and tourists every 12 months start to translate to property prices in the form of improvements. eg, a bit of spare cash, add a bedroom, add a bathroom, a a new kitchen add value etc

Again historically that average is 10% a year that feeds back into property prices doubling property prices every 10 years. Nothing new.

Thats why Mitre 10 is a mega centre, Bunnings and Placemakers are in every suburb these days. People in NZ spend money on the property. Even the Warehouse is selling paint and other DIY stuff these days.

LikeLike

A couple of comments

That’s a broad-brush-stroke generalisation – During the 10 year period you are referring to, at one point Auckland property prices were escalating a 20% pa (and we are talking about Auckland) – that happened at least over 2 years that I can remember, so I suspect your 10 year doubling doesn’t hold

Never said National were the cause of the “problem” but they sure as heck sat back and allowed it to happen

You are wrong on the mechanics of price-setting – but relax – you are in esteemed company – I have started to prepare a short thesis on the driver and the sustainers of price – but I’m not a very good writer or explainer – so it has been abandoned several times – I will get there one day – one sentence from it states

What has been noticeable has been the huge volumes of misguided opinions put forward as attempts to apply a veneer of respectability and sensibility to the myriad causes of the price of housing in New Zealand –

What is borderline recklessness is the silence of those who do know and the failure of those scribes who never think to contact those who do know – and they’re not who you might think – I do know but have never thought it my job to explain

LikeLike

I formulated my property investment logic 15 years ago and invested based on that logic. From $250k to now a $9 million portfolio $6.2 million net equity. Not to bad considering that I am wrong about the price setting mechanics.

LikeLike

Yes it does. It’s called the law of averages. If prices stay down too long then the catch up would be that much larger in subsequent years to maintain the 10 year average.

LikeLike

Of course there is also the concept of gentrification which does move the prices of specific areas at a different rate, much slower initially and then the do up and flip momentum makes for a increasingly nicer suburb that attracts a better quality owner that attracts increasing prices.

LikeLike

yes, but there is a distinction to applying a CGT to gains from implementation date (on all properties covered – eg rentals) and one only applying to properties purchased afrer the implementation date. I would strongly favour the former if we are to have a CGT – the alternative creates an even bigger lock-in effect than is inevitable in any real-world CGT.

LikeLiked by 2 people

apologies – that comment was careless – was thinking of the TOP proposal to CGT all homes

LikeLike

“A controversial $200 million plan to build the first 115 residential units above and around the North Shore’s Milford Shopping Centre has been delayed and depositers repaid their money. The project was strongly opposed by Milford residents who were concerned about tall apartment blocks in the predominately low-rise suburb. They fought against it in the Environment Court and won some concessions against initial plans for a 16-level project.”

http://www.nzherald.co.nz/property/news/article.cfm?c_id=8&objectid=11939974

Looks like as Labour tries to ramp up their 10,000 house Kiwibuild, private developers are ramping downwards building projects. Looks like extending the Bright Line Test to 5 years is just a waste of time and effort as the property market starts to slow down due to the raft of Government interventions.

LikeLike

I doubt the victory in terms of downwards price adjustment can be attributed to the new Government’s initiatives just yet. Once Kiwibuild gets going, (if it produces a supply glut) perhaps that will have some direct/positive effect.

But the present turn started as soon as the PRC moved to stem the outflow of capital and those price-makers ex-China stopped arriving by the bus load.

LikeLike

Mark Gunton and his privately-owned New Zealand Retail Property Group have had serious question marks against them for some time, some going back as far as 2010. More recently there was a lot of publicity about his Highbury Birkenhead development and the the difficulties he was having getting it off the ground. Sufficient to say the delays plus problems have been going long before the 2017 election.

http://www.stuff.co.nz/business/4473834/Westgate-cash-on-way-at-last

LikeLike

More to do ex RBNZ governor Wheelers 40% equity LVR restrictions that may be putting the breaks on buyers who have already purchased and finding that they have to pull out due to lack of sufficient equity.

LikeLike

If you want real house price charts for a large number of countries going back to 1975 (and debt to income, nominal house prices, and real house price to disposable income) look at: http://www.dallasfed.org/institute/houseprice/index.cfm . Data are updated to Q2 2017.

If you want household debt to income, check out https://data.oecd.org/hha/household-debt.htm. Data are annual, last data point December 2016.

And if you are interested in credit-to-GDP gaps (that’s credit vs credit trend compared to GDP vs its potential) from 1951 , see http://www.bis.org/statistics/c_gaps.htm. The most recent data are Q1 2017.

LikeLike