I’ve been fascinated for some time by the way elements of the right wing of the Australian business and political community have sought to lionise John Key and Bill English. On the day of his successful party room coup, Malcolm Turnbull was at it

“John Key has been able to achieve very significant economic reforms in New Zealand by doing just that, by taking on and explaining complex issues and then making the case for them. And I, that is certainly something that I believe we should do and Julie and I are very keen to do that again.”

As I noted at the time, I couldn’t think of any such “very significant economic reforms”, although there were various useful modest reforms, offsetting other backward steps.

The “look at New Zealand, why can’t we do it like them” theme has endured to the end. There was a column along those lines in The Australian the other day headed “Bill English, John Key leave NZ a far stronger economy”, by Nick Cater, Executive Director of the Menzies Research Centre, a think tank affiliated to the Liberal Party (his column is reproduced here).

The column was so full of questionable claims and overstatement that it was almost hard to believe it was written by a serious commentator. Near the start Cater notes

Key and English were described more than once as the quiet achievers. The governments they led as the bore-cons introduced reforms in tax and welfare while balancing the budget without fanfare or fuss. Seldom has the demise of a New Zealand government caused such political shockwaves on this side of the Tasman. In a period of near-universal political volatility, it raises the dispiriting possibility that simply governing well may no longer be enough. The Key and English legacy compares starkly with Australia’s record over the same period.

The first item is his list of achievements is this

In 2008, when the National Party came to power, New Zealand was 24th on the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Index, six places behind Australia. Since then the positions have been reversed. Today New Zealand is in 13th place on the index, eight positions ahead of Australia.

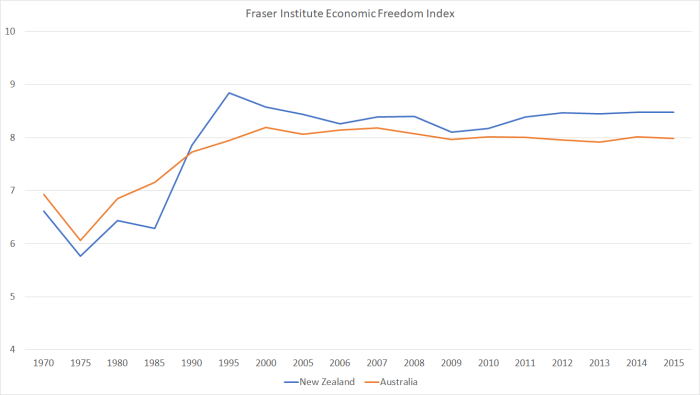

I’m not so familiar with that particular index, and tend myself to use the Fraser Institute’s economic freedom index, partly because there is a long time series of data.

The big story, for both countries, is surely that of a lot of reform and liberalisation in the 1980s and 1990s, and almost nothing material since then. On this measure, of course, New Zealand does better than Australia, and has at every reading for more than 20 years now. Perhaps New Zealand policymakers have done slightly better than their Australian counterparts in the last nine years or so but any differences are pretty small.

Cater then turns to GDP outcomes

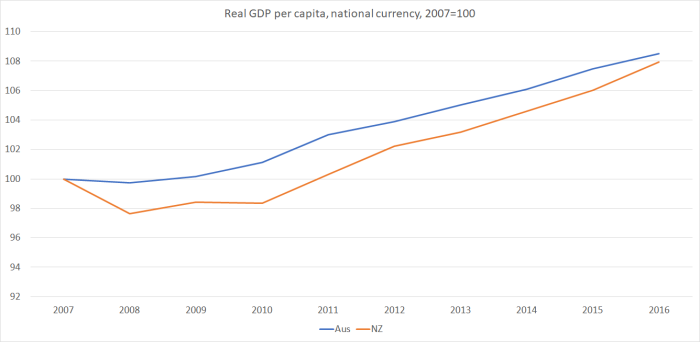

New Zealanders are still poorer than Australians on average but they are catching up fast. Nine years ago GDP per capita in New Zealand was 30 per cent lower than in Australia, now the gap has narrowed to 19 per cent.

Would that it were true, but it isn’t. Here is real GDP per capita for the two countries, both indexed to 100 for calendar 2007, just prior to the global recession..

Over that time, we’ve done just slightly worse than Australia has. Cater might argue for starting the comparison from 2008. but I doubt even he is going to credit John Key and Bill English with ending the global recession.

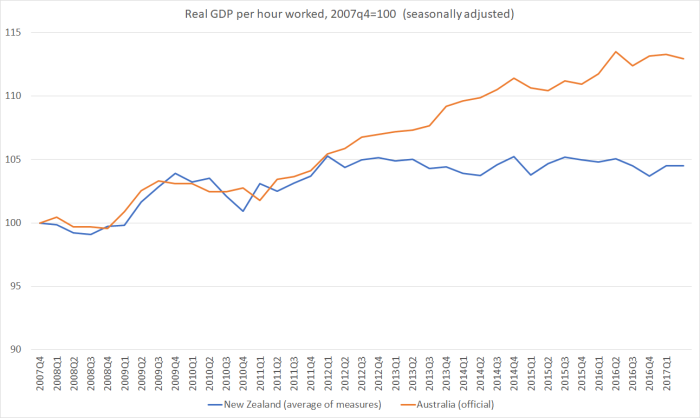

The productivity growth comparisons, of course, are particularly unfavourable to New Zealand, esepcially over the last five years.

Productivity is something closer to what government policy can usefully and materially influence (although other stuff matters too).

If we assume that governments have the power to control the economy — which incidentally 33 per cent of Australians no longer believe, according to the most recent Australian Electoral Study — then Key and English governed exceedingly well by almost any measure.

On the bits governments have a fair influence over we’ve done particularly badly relative to Australia (less badly relative to some other countries). But there are bits of the economy that national governments have almost no control over whatever. Commodity prices are perhaps foremost among them. Our government can’t do anything much about the dairy price and the Australian government can’t do much about, say, iron ore prices. Fluctuations in the terms of trade affect real per capita income measures even when the volume of production doesn’t change.

Australia had a huge terms of trade boom up to 2011, and even now if we take the last 15 years as a whole Australia’s terms of trade have increased more than ours have. But since 2007/08, our terms of trade have done a bit better than Australia’s. Hard to see how governments on either side of Tasman deserve credit or blame for those developments.

But as a result of these terms of trade swings, on a measure that adjusts for the effects of the terms of trade (real GDI per capita), New Zealand has grown three percentage points faster than Australia since 2007. A nice-to-have windfall to be sure, but (a) even that gap makes only tiny inroads into the accumulated levels differences between New Zealand and Auatralian incomes, (b) the terms of trade are volatile, and who knows what they’ll do to the income gaps in the next decades, and (c) in the long-run, productivity growth is almost everything, when growth in living standards is in question.

As Cater notes, there has been a big change in trans-Tasman immigration (although even those flows have been quite – typically – variable over the last nine years).

The relative change in economic fortunes has changed the migration flow across the Tasman. Inward migration from Australia exceeded outward migration last year for the first time in a quarter of a century.

Of course, that last time – quarter of a century ago – was when the Australian labour market was also doing very badly. New Zealand’s was as well, but when you are looking at moving to another country, conditions in the destination market matter a lot. Australia has struggled in the last few years, but actually both countries are still among the diminishing number of advanced countries where the unemployment rate is still well above pre-2008 downturns levels. That reflects no great credit on governments, or central banks, on either side of the Tasman.

Then, of course, there is a fiscal policy. Personally, I think the outgoing government has done a pretty reasonable job on that score – as, in fact, its predecessors for the previous 20 years had done.

But even here Cater gets some things quite badly wrong

While treasurer Wayne Swan was doling out cash and spending billions on poorly conceived make-work projects to help Australia survive the 2008-09 financial crisis, English gave personal and business tax cuts.

I’m no fan of the Rudd/Swan fiscal stimulus programme, but….. the appropriate comparison here is that we had no active discretionary fiscal stimulus to attempt to counter the recessionary forces. None. And the almost accidental stimulus that happened to be in place resulted from the Budget choices of the outgoing Labour government which had put in place tax cuts and spending increases at a time when Treasury was advising them that the government accounts would remain in surplus even after those initiatives.

Of course, there were some tax reforms here – in 2010 – and conventional wisdom tends to count them “a good thing” (I’m less convinced, because the package of measure increased the effective taxation levied on capital income, against the prescriptions of standard economic analysis). But I’m not aware of any analyst who thinks those changes made a material difference to New Zealand’s economic performance in the last few years.

Cater quotes some debt numbers that I don’t recognise

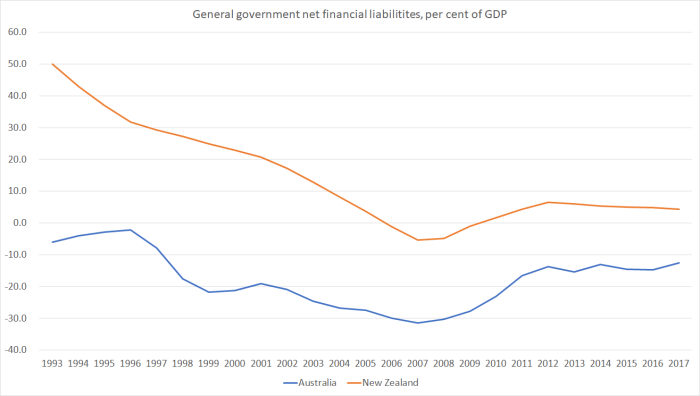

Today the New Zealand budget is in surplus while Australia is still running deficits. Ten years ago the New Zealand government’s gross debt stood at 25 per cent of GDP while Australia’s sat on 20 per cent. Today the positions are reversed. Australia’s net public debt is at 47 per cent; New Zealand’s hit a peak of 41 per cent in 2012 and has steadily declined to 38.2 per cent.

Here are the OECD’s number for general government net financial liabilities as a share of GDP.

Every year for the last 25, Australia’s overall government net debt has been less than ours, and if the gaps between the two countries has closed a bit in the last few years, the change is pretty small and the similarities, in the respective paths, are more striking than the differences. Of course, we’ve had one nasty shock they haven’t had – earthquakes. Then again, they’ve been coping with a really big correction in the terms of trade.

On both the tax and spending sides of the government accounts, we have a slightly bigger government (share of GDP) than Australia – and more variable one. None of that has looked like changing over the last nine years.

Perhaps you thought this was just an economic case. But, no. Cater is just getting into his stride.

The achievements of Key and English are by no means limited to the economy, however.

Cater appears to be a big fan of the “investment approach” to welfare and related government spending. I’m still more ambivalent – the use of data appeals, of course, but big-government joined-up data makes me very nervous (hints of, eg, Chinese social credit scores). For now, I’m happy to look for evidence of results. Cater is convinced.

From this thinking flowed a new approach to welfare that has since been adopted by the Abbott and Turnbull governments to great effect.

and

In its second of two [three?] terms the National government first halted the long-term trend of rising welfare dependency and then reversed it. The number of New Zealanders claiming sole parent benefit has fallen by a quarter as 20,000 single parents found work. Long-term welfare dependency has fallen substantially. In 2012 78,000 New Zealanders had been collecting benefits for 12 months or longer. By June this year the number had fallen to 55,000.

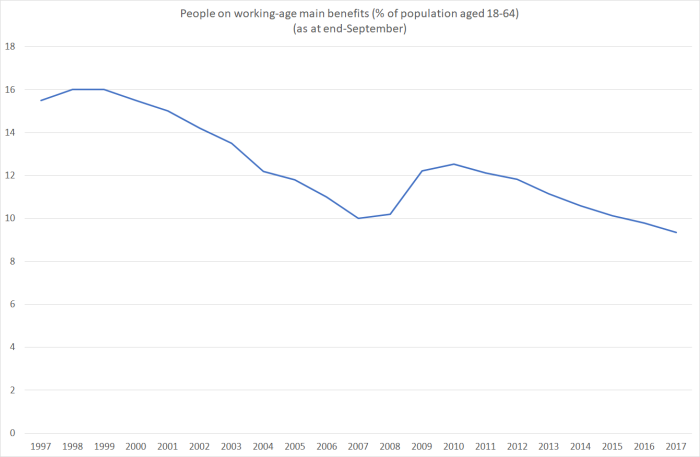

The first sentence is simply wrong. Here is the MSD data on the number of working-age main benefit recipients as a percentage of the population aged 18 to 64.

There was a recession in the first term – welfare benefit numbers rise in recessions – and then the downward trend that had been in place for the previous decade resumed. But as of last month, the share of the working age population on these main welfare benefits was only very slightly below where it had been in September 2007.

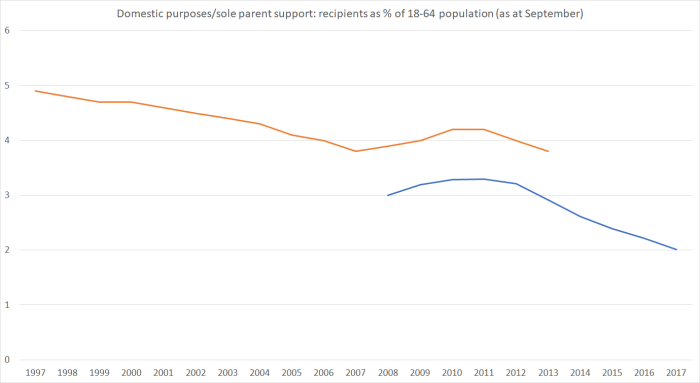

In a way, that isn’t surprising. Unemployment is still well above pre-recession levels. But it should be somewhat troubling, both on that count, and because one component of benefit numbers has dropped away quite sharply. As Cater notes, the number of sole parents on the benefit has fallen away a lot. Here is the chart – there is a discontinuity in the series associated with the welfare changes (including labelling changes) in 2013.

The trend was underway during the decade prior to the recession. The pace of decline has certainly accelerated since then (at least since 2013), but since the overall number of benefit recipients as a share of the working age population hasn’t changed since 2007, other categories must have increased.

It would also be interesting to see a serious study of just what role policy changes have played even in the decline in sole parent beneficiaries. After all, teen pregnancy rates have been dropping globally – for reasons not, I think, that well-understood – and in New Zealand the teen birth rate halved between 2008 and 2016 (but, even so, was still higher than the comparable rate in Australia). Welcome as that trend is, it seems unlikely that New Zealand government policies will have been a large part of the explanation.

And, of course, over the outgoing government’s term there has been a huge increase in the number of elderly age-benefit recipients (2011 saw the first baby-boomers turning 65). In the last months of the outgoing government, there was finally talk of lifting the age of eligibility – something Australia began years ago – but it was going to happen 20 years hence. And now – for now – it isn’t going to happen at all.

At this point, Cater leaves the numbers behind.

The government’s strategy of taking the public with them on reforms, explaining the logic well in advance in language people could follow, adjusting expectations and then implementing the promised changes, was remarkably successful until the end.

On what measures I wondered?

And he concludes

For 11 years he and Key had written a counter-narrative to that prevalent in Australia that reform was all but impossible in the era of Facebook and Twitter. While Australia appeared stuck in a policy drought, New Zealand was breaking new ground, discovering new ways to measure government programs by their results and finetuning them accordingly. Feel-good policy, sentimentalism and identity politics were anathema to them.

English and Key proved that centre-right parties were not condemned to be nasty parties, focused on numbers rather than people, as they doggedly cleared up their predecessors’ fiscal mess. Devoid of ideology, fiercely pragmatic, self-aware and inspired, the pair stands as inspiration to the rest of the developed world in these anxious and volatile times.

So horrendous house prices, no productivity growth, an export sector shrinking as a share of GDP are the sorts of things that provide an inspiration to the world? I’m flabbergasted. The terms of trade have certainly been favourable, and yet even the outgoing Minister for Primary Industries has been heard to talk of the possibilities of “peak cow”. Where exporters haven’t done badly, it has too often – export education and dairy being prime examples – been partly a result of unpriced subsidies and environmental externalities.

Relative to Australia, the story of the last nine years isn’t all bad. Neither country has been managed that well. There are some good stories. Broadly speaking, New Zealand’s fiscal policy is one of them, but too much can be made even of that. A much lower balance of payments current account deficit is often counted as another good story, except that much of the contraction reflects (a) the slump in global interest rates, reducing the cost of our external indebtedness, and (b) the weakness of investment even years into the recovery phase. Perhaps we’ve had tidy stewardship, but going nowhere. A safe pair of hands at the bridge perhaps, but with the ship meandering without clear direction, or any compelling sense of how better outcomes might be achieved.

All of which should not be taken as any sort of enthusiasm for the new government. No doubt – like their predecessors – they’ll do a few sensible things. But, like their predecessors, at present they (or the constituent parties) show little sign of either understanding the nature of New Zealand’s dismal long-term economic performance, or of adopting the sorts of policies that could at last begin to reverse that decline. A pessimist might incline to the view that things may even get gradually worse – and here I’m not thinking of the cyclical pessimism Winston Peters was enunciating on Thursday night.

There have been very few periods in the last 150 years when policy has been much better managed in New Zealand than in Australia. The last nine do-little-or-nothing years (following on from a similar nine years) hasn’t been one of those periods. That is to the credit of neither New Zealand or Australian politicians, but of course Australia’s starting point is so much less bad than ours.

At the time, Turnbull was faced with a $40 billion deficit on the Australian Treasury Books. NZ with a small surplus and a economy growing at 3% would have looked like a great achievement.

LikeLike

Certainly Turnbull’s challenge was the bigger one. Imagine how many low skill, low wage immigrants they’d have to bring in by the tanker load to match NZ’s ‘growth’.

LikeLike

In the interest of accuracy – it was Tony Abbot who inherited the $40 billion deficit – and under his stewardship it only got worse – then they rolled Abbot

LikeLike

The Deficit was small and getting smaller as a % of GDP. If you use accrual accounting it is around 0.5% of GDP or a balanced budget.

you are comparing apples with oranges. Remember we had a reduction in the terms of trade which meant a small nominal GDP outcome. Very important for budget outcomes.

LikeLike

You can’t use accrual accounting when you actually have a cashflow operating deficit of AUD 40 billion that you need to go into the debt market and issue Australian Government bonds in order to fund the spending shortfall. In other words, go on your knees and beg China to take up those Treasury bonds.

LikeLike

The point is about apples for apples comparisons. NZ govts use accrual accounting ,and our numbers are all reported that. We still run what are known as residual cash deficits and still have to issue bonds.

LikeLike

Growing up in Scotland I learned that Scotland beating England at soccer was more important than say Scotland winning the world cup. As an Englishman we proved we were intellectuals by placing French phrases in our conversation. My French son has taught me that the French would never compare themselves with the English but live with a severe chip on their shoulder about the Americans and see Germany as their benchmark. When I lived in New York the comparison was a nostalgic one with Europe; the New Yorker and the NY Times being full of references to aristocratic and artist life in Britain.

Comparisons with Australia litter our newspapers from the front page to sports pages via the arts pages. It is unusual to hear of Australians comparing themselves with New Zealand but it seems to be the semi-obsession of Kiwis to compare themselves with Australia. You see T-shirts saying ‘I support anyone who is playing against Australia’ but I doubt you see the reverse across the Tasman.

If economic success depends on governance, geography, history and sheer random luck it is hard when comparing Australia with New Zealand to identify what has been the result of government actions. A better comparison might by South Island and Tasmania, Sardinia and Corsica, various Caribbean and PI countries.

Government makes a difference: North and South Korea would be an extreme example. But the 33% of Australians may be right: the governments of OECD countries could be interchanged with minor economic results.

LikeLike

Oh dear

The Menzies Research Centre is an independent think tank associated with the Liberal Party of Australia. The Centre was established in 1994 to undertake research into policy issues which will enhance the principles of liberty, free speech, competitive enterprise, limited government and democracy. The Centre publishes policy monographs and books, holds conferences and has an extensive research and lecture program

Much of what you quote reads of Curated Political Spin

A google search of Nick Cater does not produce a flattering set of results an aspiring captain of industry would want

LikeLiked by 1 person