When I was very young one of the picture books I enjoyed – favourably reviewed, so I see now, even by the New Yorker – was Richard Scarry’s What do people do all day? Set in Busytown, there was a pervasive sense of activity and, well, busyness. I don’t think the book had a separate entry for government policy advisers, but the book came to mind as I reflected on a Treasury guest lecture I went to yesterday.

A recently-retired MBIE official had been invited by Treasury to share her experiences of 10 years in the regional economic development wing of MBIE (or its predecessor the Ministry of Economic Development (MED)), and the title of the lecture was “The Great Cat Muster”. At the start of the lecture she asked us to observe Chatham House rules, by which she meant that anything she said could be reported, but that she shouldn’t be identified. I’m not sure why, when the flyer for the presentation is easily accessible on Treasury’s website, but for my purposes the presenter’s name probably isn’t very important. The worry is that her content epitomised a cast of mind that can too easily pervade official bureaucracies. As I summed it up last night to another attendee “all that energy and good intention, with so little of an analytical framework and even less evidence”.

We weren’t off to a good start when she briefly ran through her various roles in regional development. In the first of them she had, apparently, been responsible for the West Coast timber settlement. But, as she noted – and full marks for candour I suppose – when the NZIER later rated the policy paper on this issue (as they do for a bunch of participating ministries), it scored the worst rating MED had ever achieved.

But most of her time had been spent on more pro-active government initiatives. There was something called the Food Innovation Network, work on Maori economic development, and then for the last few years work as part of the flagship Regional Growth Programme. The presenter was clearly pretty passionate about what she’d been doing and the relationships she’d been building. There was no shortage of energy or ambition. And no shortage of central Wellington perspectives either. There were countless working groups, and charts to illustrate complex networks across central government and between arms of central and regional governments. Meetings abounded, briefing papers multiplied, Air New Zealand profited from frequent flights, relationships were built, and sometimes the recalcitrant were called into line, or simply bypassed. At one point, she even celebrated the “fact” that regional governments had mostly simply chosen to ignore an act of Parliament – for the greater good no doubt. And as for the private sector, well……..the government had simply had to be involved in the Food Innovation Network because we had to develop our food industries, and add value to our exports, and they had found that the private sector was “terribly unsophisticated”.

We learned about the regional studies that have been conducted in several areas under the auspices of the Regional Growth Programme, itself initially sponsored by three ministers (and their agencies). Now there are “action plans” sponsored by even more minister and agencies. One mayor had apparently finally been convinced by wise officials that one particular product did not represent his district’s economic future.

It was all remarkably busy. I had to sympathise with the senior manager who, she recounted, had asked her of one programme “can you be sure we can contain this?”. To which her response had been along the lines of “well, no, I can’t. You’ll just have to trust me”.

But, since this presentation was being held at The Treasury, and MBIE is purportedly an economic agency, a few simple things struck me as missing. There was little or no sense of any of the myriad ways in which governments and official agencies fail, and sometimes leave things even worse than when they started. There was nothing at all, even in passing, on what the market failures might have been to justify all this busyness in pursuit of regional economic development. Hadn’t we been this way before, numerous times (one of my earliest political memories is of Matai)? And, for all the busyness, what difference had all this regional development promotion activity actually made. After all, there had been no national productivity growth for the last five years, and although she several times highlighted the idea of boosting export industries, exports as a share of GDP have been falling.

So when question time came I stuck up my hand and asked what the market failures were, and how different things would have been if none of this activity had gone on.

Her response was that the market failure was “information asymmetries”. It wasn’t at all clear what she thought she meant by that phrase, but she seemed to have in mind some sense that central government knew stuff people in the regions (private sector or government) didn’t. Public servants had needed to “explain to regions where they fit in the system”. That just isn’t what any economist means by the sort of information asymmetry that might – just possibly, under some circumstances – warrant government intervention. But then it got even worse. She declared that she’d come from a family that didn’t rank public servants very highly, but “I’ve come to realise that public servants see things no one else sees”, and can offer a “strategic perspective”.

She overlooked answering the second part of my question, so when other people had asked their questions, I asked again what difference all this regional development promotion activity had actually made. And there was a brief moment of dawning unease: “I sometimes ask myself that”. She went on to claim that the effects can’t necessarily be quantified by statistics, and that the gains might take more than a few years to realise, but that if we didn’t “do something” we’d see the eventual effects of that.

What stunned me, in someone invited to give such a public lecture at Treasury, was the lack of any rigour, the lack of any robust framework, around all this effort. Not that many years ago, we’d have counted on The Treasury to be particular intolerant of such, apparently, woolly enthusiasm (at the taxpayer’s expense). But no longer? I’d like to think that somewhere in MBIE or Treasury there is a somewhat more hard-headed assessment and evaluation going on, but….it wasn’t on display yesterday.

(And, as one other sceptical attendee described it to me, most of the other attendees – I suspect mostly public servants – appeared to be “lapping it up”. I really hope that assessment is wrong, but there were no other sceptical questions from the floor.)

In a way, perhaps, one of the MBIE staff in the audience summed up, unwittingly, the problem with much of this. He noted that they have “been focused on the levers we can pull easily”, while ignoring others. And with, it seems, no hard-headed analysis as to whether levers MBIE can’t pull might be considerably more important than those they can – I think, most notably, of the real exchange rate.

And what of the regional economies? How have they been doing? To have listened to the presentation one might have supposed they were wastelands of poverty and economic failure, remarkably different from the urban centres of Auckland, Wellington and Christchurch.

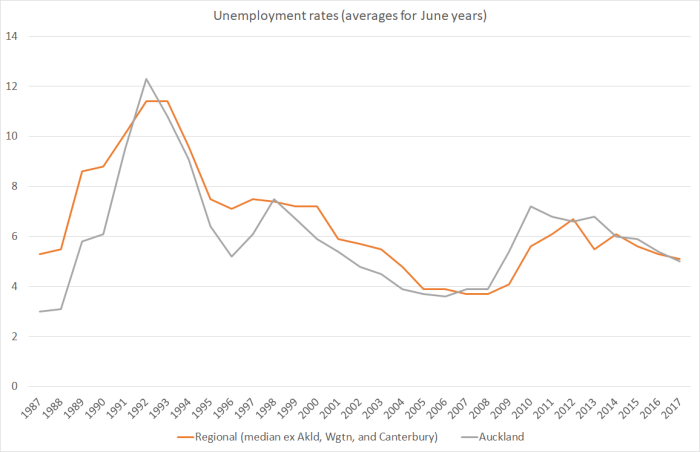

But the data don’t really seem to back up that sort of story. Take the unemployment rate for example. Here is a chart showing the median unemployment rate for the regional council areas other than Auckland, Wellington and Christchurch against the unemployment rate for Auckland.

For most of the last decade, Auckland’s unemployment rate has been a bit above that in the median non-urban region (even though theory typically predicts that a big urban area will typically have a slightly lower unemployment rate – skill matching is a bit easier in a deeper market).

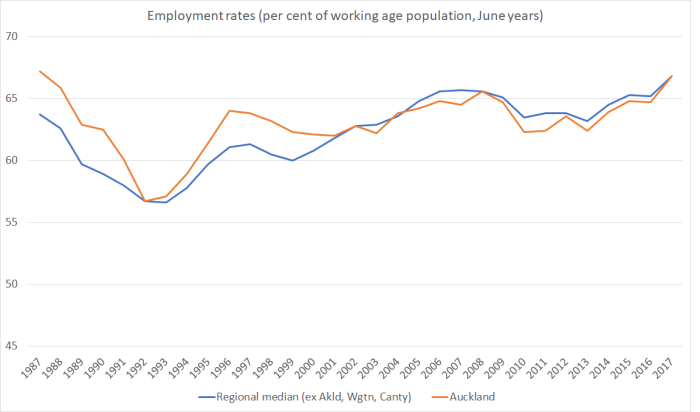

Or the same chart for the employment rate.

For the last 15 years, the employment rate in the median region has typically been a touch higher than that in Auckland.

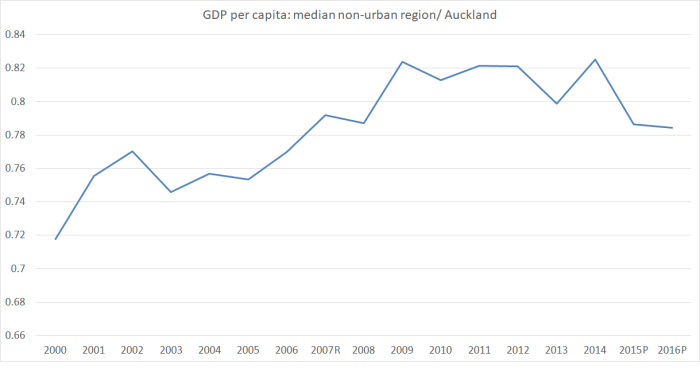

What about regional GDP? In earlier posts, I’ve pointed out that Auckland has been seriously underperforming relative to the rest of New Zealand: not only is GDP per capita relative to the rest of the country low compared to what we see for big cities in typical advanced countries, but that margin has been shrinking since 2000. The flipside of that, of course, is that the non-Auckland bits of the country have been doing okay on this measure (not absolutely – New Zealand’s overall productivity record is poor – but better than Auckland).

This chart shows the GDP per capita of the median non-urban region relative to GDP per capita in Auckland (I could have used the median of the three big urban areas, but in every single year Auckland was the median).

In the last couple of years – for which SNZ still label the data provisional – the median region has lost a bit of ground relative to Auckland (big building booms to accommodate population surges tend to do that), but (a) over the last decade the regions have lost no ground, and (b) over the full period since 2000 they’ve made quite a bit of ground on Auckland.

There just doesn’t seem to be much in the data to warrant government regional economic development programmes, even if one believed – as I don’t – that such programmes might make any material useful difference to economic outcomes. Markets work when governments let them, and governments are better advised to focus on getting the overall parameters of economic policy set right – tax rates, regulation, even immigration policy – and let activity then occur where it will. The private sector won’t typically or consistently be slow to seize opportunities, and when they get things wrong mostly they are the ones who live with the consequences. When officials and ministers spend lots of our money on busy programmes signifying much and accomplishing little, then not so much.

Looking through the glossy document MBIE put out (they do those really well), under the auspices of three ministers, it was hard not to conclude that the whole programme had probably been more about being seen to be busy, and shoring up the National vote in the provinces, than about making a material difference to economic performance.

Reblogged this on The Inquiring Mind and commented:

Michael Reddell looks at the nonsense which surrounds us and suggests that much analysis is in fact just assertion.

LikeLike

Describe the make up of the audience – what do you have to do to get an invite – were you there as a guest speaker? A supernumerary? Have they allowed you to keep your swipe-card

LikeLike

It is an open invitation to anyone interested. Nothing underhand or specific to me at all. Indeed, you too could sign up here http://www.treasury.govt.nz/publications/media-speeches/guestlectures

(And I commend Treasury on running the series, which often has interesting and stimulating visiting speakers. Alan Bollard, for example, is speaking next week, although as it is school holidays I won’t be attending,)

LikeLike

Thanks

LikeLike

Your last paragraph is looks to be accurate

From her LinkedIn profile

Tai Tokerau Regional Growth Study and Action Plan – Starting January 2014

The Tai Tokerau Northland Growth Study launched in Feb 2015 set the platform for the Tai Tokerau Northland Economic Action Plan launched in Feb 2016. The value of this work is not in the reports themselves but in the relationships built and the shared understanding of and commitment to some key actions. It needs all parties to understand their roles in the economy and to work together to address long term, deeply entrenched issues that will support better economic and social outcomes for this region.

Team members: Sue Dobbie

LikeLike

What is the point of having a public lecture program under Chatham house rules? Most people do not understand what they mean anyway

LikeLike

Indeed. There might be something in applying that approach to, say, naming anyone asking a question.

On this occasion, she did at least articulate her meaning of Chatham House – seemingly oblivious to the flyer sitting on the website – which I have sought to comply with.

LikeLike

Easy to see why someone (may have been Douglas Hurd?) once remarked that the civil service thought Yes Minister was a training video. By the sounds of this, Sir Humphrey would have been right at home in MBIE.

LikeLike

“”A key aspect of the government’s support for the regions is the appointment of a Senior Regional Official as a single representative for government at the regional governance level. The Senior Regional Official is a deputy chief executive from a government agency who advocates for the region and coordinates government support. “”

Maybe instead of sending a senior person out to the region they could do it in the opposite direction – find a local person broadly accepted by and knowledgeable of the region and send them to do battle with the government’s bureaucracy to get the best deal they can manage for their region. They would need an office in Wellington but would spend much of their time home in the region listening to disgruntled local business men & women. We could call them MPs. They are expensive but overall it would be a saving on another level of bureaucracy and many glossy reports.

Please follow up this article with an appraisal of ATEED. It must be a failure of my imagination but try as I might I just can’t work out what they do that benefits New Zealand.

LikeLike

This article triggered a momentary interest in what is actually being done which led to: http://www.northlandnz.com/media/documents/Tai-Tokerau-Northland-Economic-Action-Plan.pdf

and on page 8 “point 4.3. BEING PART OF THE ACTION PLAN” there is a list of key benefits:

1. Networking and collaboration

2. Being part of the success story

3. Access to expertise, support and advocacy for economic development projects

And I think I can see where they have gone wrong. If you are successful you know it and don’t need a quango to boast about it. Replace that with ‘autopsy’ and ‘find the guilty party’ and they would have a chance. Nothing beats learning from failures, preferably others’ failures.

LikeLike

You guys just know how to criticise. It sometimes makes me wonder: have you ever done anything useful for New Zealand? Let us know if you have.

LikeLike

Well I retired so no chance of launching more computer software. You might think that useful. Before that I may have helped you very indirectly if you ever signed a contract to purchase property. Also provided significant software enhancement that helped export of aircraft parts.

Quite seriously the point is who is measuring whether tax-payers (such as you) are getting value for your money. Maybe you are and maybe you are not. A commercial business would set targets and measure against them.

Where it does get interesting is how to measure performance in the civil service. I find persuasive the idea that attempting to measure teaching productivity is counter-productive. Watching a friend’s cancer treatment I was very impressed by the quality service provided – any time and motion expert would have cut down on the meetings with nurses and doctors and made meetings far shorter and that would have been disastrous but you had to be there to realise why. The IRD help line now takes forever to get through whereas 15 years ago it was quick. That must mean IRD staff are not now sitting around waiting for calls – efficient use of their time but not the best result for NZ in my opinion.

The question “what are you doing and why” applies beyond bureaucracies. I remember working hard supporting a retail software installation when the big boss asked why I hadn’t I delegated the task to the user. He was right and until that moment I had been proud of my effort.

LikeLike

Societies – at least democracies- advance by scrutiny and challenge. When it is public institutions involved there is, after all, no market test. When leading public institutions – in this case Treasury – promote something, I don’t feel any compunction about exposing what is presented to scrutiny.

LikeLike

Looked at the MIE doc. —- the opening picture was a hot-air balloon—- how appropriate

LikeLike

As an official who was not able to make the lecture, I’m now sorry I missed it, especially question time. But your observation about “easy levers” sounds very familiar, and is a symptom of overwork, whether the work is justified or not…

LikeLike

[…] to maintain – is going to transform the sort of flabby thinking around regional development presented at Treasury late last […]

LikeLike