It has been a quite remarkable rookie error by the Labour Party that allowed the mere possibility of specific tax increases to become such a major part of the election campaign, in a climate where the government’s debt is very low, and where official forecasts show surpluses projected for years to come. If government finances were showing large deficits, and there was a desperate need to close them, that political pressure might have been unavoidable. Closing big deficits involves governments taking money off people who currently have it – by whatever mix of spending cuts or tax increases – and doing so in large amounts. But the PREFU had growing surpluses, and Labour’s fiscal plan had almost identical surpluses for the next few years – without relying on any further tax changes that might have flowed from the recommendations of the proposed Tax Working Group.

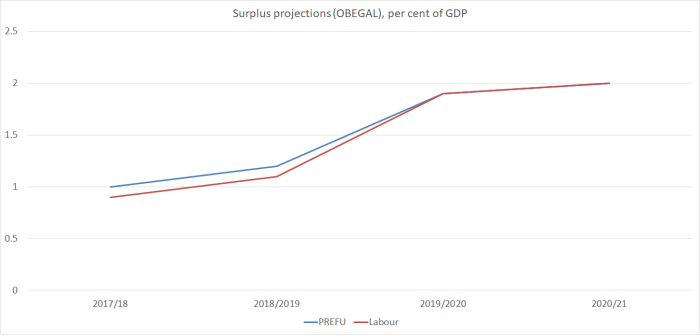

These are the surplus projections

Of course, Treasury GDP forecasts can’t always be counted on – and it is seven years now since the last recession – but there is quite a large buffer in those numbers even if the economic outlook changes. But the other side of politics wasn’t disputing the (Treasury) GDP assumptions. And it seems to have been lost sight of that in a growing economy, with low and stable debt levels, modest deficits (on average) are the steady-state outcome (consistent with low stable debt). That might involve decent surpluses in boom years, and perhaps quite big deficits in recession years (as the automatic stabilisers work on both sides) – but again the Treasury numbers, which both sides are basing their numbers on, say that at present we are in the middle (estimated output gap around zero, unemployment still a bit above a NAIRU, and on the other hand the terms of trade above average).

I guess it was always the sort of risk Labour faced in changing their leader so close to the election (things move fast and something – who knew what specifically – was almost bound to not work out well), but it was all so easily avoidable. They could have:

- stuck with the Andrew Little policy (now reverted to) of no changes flowing out of the TWG process to come into effect before the 2020 election,

- they could have reverted to the 2014 policy (a specific detailed capital gains tax proposal, perhaps including revenue estimates), or

- they could have committed to any package of TWG-inspired changes implemented before the next election being at least revenue neutral (if not revenue negative). This latter sort of commitment would have been easy to make precisely because of the large surpluses in the projections both sides are using (see chart above).

After weeks of contention and uncertainty – some reasonable, some just fear-mongering – they’ve finally adopted the first option.

But you have to wonder what the proposed Tax Working Group will be left to do? In practice, it looks as though it might most usefully be described as a capital gains tax advisory group – to advise on the practical options and details on how to make a capital gains tax work, as well perhaps as to review the evidence and arguments for (and against) such an extension to our tax system (my reflections on the CGT option are here).

They’ve ruled out increases in personal or company tax rates, they’ve ruled out GST increases, and they’ve ruled out a land tax affecting the land under “the family home” (which is most of the value of land in New Zealand). They apparently haven’t ruled out revenue-neutral packages that involve a reduction in income tax rates, but this looks like a pretty empty suggestion. Why?

The first reason is that they claim that their suite of policies are going to solve the housing crisis. I’m a bit sceptical about their claims (and those of the government), but if they are right, how much revenue do they suppose there is likely to be from a capital gains tax anytime in (say) the next 20 years? Treasury once produced some rather large revenue estimates, but (from memory) they involved some sort of muted extrapolation of the experience of the previous 20 years. Both sides of politics seem to think they can stabilise nominal house prices, and then let income growth and inflation reduce real prices and price to income ratios. If so, there are no systematic capital gains on housing – and idiosyncratic ones (particular cities or specific locations that do well) won’t add to much revenue at all. Of course, it might be different if the housing measures fail, but Grant Robertson yesterday seemed pretty adamant.

“What we are signalling is, the Labour Party’s policy is that our focus is on fixing the housing crisis. That is our focus.

A capital gains tax might (or might not) be a sensible addition to the tax system, but it shouldn’t raise much money.

What else is there? I’m sure tax experts have various small things they’d like the working group to look at, but it is hard to believe there is anything that could raise much revenue. For some, a land tax looked promising – my own scepticism is here. But Labour has now ruled out a tax on the land under “the family home”, which effectively nullifies any possibility of a sensible, credible, and enduring land tax.

It is one thing to rule the family home out of a capital gains tax net. Even for most of those left liable for capital gains tax (CGT), the effective liability can be deferred for many years (reducing the present value) simply by not realising the gain (not selling the asset). That is even more true with the sort of institutional holders than many seem keen to encourage into the rental market. And, of course, there is only a liability if prices actually go up. Those are among the reasons why the overseas literature tends to find little evidence that a CGT would make much useful difference to the housing market.

A land tax would be different. It is a liability year in, year out. Owner-occupiers (and associated trusts etc) wouldn’t pay it, but everyone else would. It would be a huge change in the effective cost of (say) providing rental services.

New Zealand real interest rates are the highest in the advanced world. A very long-term real government bond rate is around 2.5 per cent at present (the real OCR is currently zero or slightly negative). So suppose a government imposed a 1 per cent per annum land tax on land not under owner-occupied dwellings. Relative to a risk-free rate of, at most, 2.5 per cent that would be a huge impost (40 per cent of the implied safe earnings of the asset – the appropriate benchmark since the tax itself isn’t risk-dependent.) It would dramatically lower how much any bidder who wasn’t planning to live on the land could afford to pay for the land – by perhaps as much as 40 per cent.

That might sound quite appealing. Rental property owners (actual and potential) drop out of the market and land (and house+land) prices plummet. But wait. Wasn’t the political promise that they weren’t trying to cut existing house prices? And what about the people who – because of youth, or desire for mobility – don’t want to own a house and positively prefer, for time being at least, to rent. And what about farmers? Lifestyle blocks (presumably exempt from the land tax) instantly become much more affordable than farming (which presumably does face the tax). To what social or economic end?

Attempt to impose such a land tax and my prediction would be (a) that it would never pass, since it would represent such a heavy impost on a large number of people (and yet on not enough to raise enough revenue to allow meaningful income tax cuts to offset the effect), and (b) if it did pass, exemptions and carve-outs would quite quickly reduce it to the sort of land tax we actually had in New Zealand only 30 years ago – which only affected city commercial property.

Now perhaps there is a limited middle ground. There is a plausible case that can be made for use of land value rating by local councils rather than the capital value rating system that most councils now use. I’m not aware that we have good studies suggesting better (empirical) outcomes in places that still use land value rating, but the theory is good. The problem, of course, is that by ruling out a land tax on the family home, Labour would appear to have ruled out (say) using legislation to encourage or compel councils to rely more heavily on land value rating. Perhaps that might leave undeveloped land within existing urban areas as potentially subject to land value rating? There might be some merit in that, but the potential seems quite limited.

So, as I say, it looks as though the proposed tax working group should really just be a CGT advisory group.

And that would be a shame because, whatever you think of the merits of a CGT, it isn’t the only issue that would have been worth addressing in a proper review of the design of our tax system. For 30 years now – since what was a fairly cynical revenue grab (recognised at the time by those involved) in 1988/89 – our tax system has systematically penalised returns to savings (both relative to how we treated those returns previously, and relative to how other countries typically treat such returns). The prevailing mantra – broad base low rate – which holds the commanding heights in Wellington sounds good, until one stops to think about it. We have modest rates of national savings, and consistently low rates of business investment – and our productivity languishes – and yet the relevant elites continue to think it makes sense to tax capital income as heavily as labour income. It doesn’t, whether in theory or in practice. They don’t, for example, in social democratic Scandinavia. They don’t – when it comes to returns to financial savings – almost anywhere else in the advanced world. We should be looking carefully at options like a Nordic system, a progressive consumption tax, at inflation-indexing the tax treatment of interest, and at whether interest should be taxed (or deductible) at all.

Plenty of people are worrying about the potentially radical nature of some aspects of a possible new left-wing government. I come from the market-oriented right on matters economic, but I worry that in these areas they won’t be radical enough – won’t even be willing to open up the serious issues that might be contributing to our sustained economic underperformance. And frankly, when the debt levels are as low as they now, and sustained surpluses appear to be in prospect, if ever there is a time to look at more serious structural reforms it is now. It is a great deal easier to do tax reform when any changes can be revenue-negative (actually the approach taken by the current government in 2010 – see table of static estimates here) or (depending on your orientation) used to increase public spending. But it looks as though another opportunity is going to be let go by. That would be a shame.

(Having mentioned the 2010 package in passing, I am a little surprised that the increase in the effective rate of business taxation in that package doesn’t get more attention. It often passes unnoticed because the headline company tax rate was reduced, but as the published Treasury assessment at the time put it

While the tax package lowers the company tax rate, changes to thin capitalisation rules and depreciation allowances mean that, on average, firms will pay more tax as the reduction in the company tax rate does not fully offset the impact of higher taxable income owing to the base-broadening measures. As a result combined company and dividend tax revenues are estimated to be about 3-4% higher than in the absence of the package. In the case where all investment is financed by equity, this could increase the user cost of capital by about 0.6%.

Using the New Zealand Treasury Model (NZTM) we estimate that the increase in the user cost of capital leads to the private business capital stock reducing by 0.45% compared to what would have been the case in the absence of the package.

Not obviously a desirable outcome for an economy that had, for decades, had low levels of business investment.)

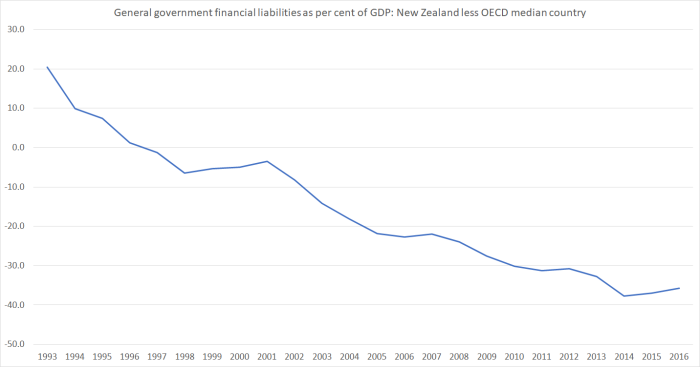

And finally, a chart showing in just what good shape New Zealand public finances are relative to those in the rest of the advanced world. New Zealand government debt has increased relative to GDP under the term of the current government (mostly some mix of a recession and earthquakes), but government debt as a share of GDP has increased in most other countries too. Here is the gap between New Zealand and the median OECD country, using the OECD’s series of general government net financial liabilities. Our net financial liabilities last year were around 5 per cent of GDP on this measure (seven OECD countries have less net debt, or have net assets). The median OECD country has net financial liabilities of 40 per cent of GDP. But here is the gap, going back to 1993 when the data commence for New Zealand.

It is quite a striking chart – and took me a little by surprise frankly. If you didn’t know when the two changes of government had occurred, there would be no hint in this chart. For almost 25 years now we’ve kept on lowering our net debt relative to that of other OECD countries, through good times (for them and us) and for tougher times, under National governments and Labour ones. There just isn’t any obvious break in the series. And as we have a lot fewer off-balance sheet liabilities (eg public service pension commitments) the actual position is even more favourable than suggested here.

I’m not a big fan of increasing government debt as a share of GDP – and low as current interest rates are (a) productivity growth is lower still, and (b) our interest rates are still the highest around. But you do have to wonder quite what analysis backs up the drive for still lower rates of government debt to GDP, absolutely and relative to the rest of the advanced world. And persisting with the “big New Zealand” strategy of rapid population growth makes the emphasis on very low levels of government debt even more difficult to make much rational sense of.

I did wonder if Robertson/Ardern were leaving the option open for lower taxes on savings and higher taxes elsewhere to achieve an overall tax neutral change. They might want to do this to improve the incentives for investing in productive capital. This tax change designed to work alongside a move away from investing in unproductive capital (bidding up the prices of existing houses), which is achieved by regulatory reforms to planning, infrastructure etc.

LikeLike

the Labour tax document released yesterday explicitly says “The Working Group will not consider increases to personal income or corporate taxes, or GST rates”, sadly not even as part of a rebalancing of the sort you suggest.

LikeLike

Lower taxes on savings equate to higher savings. Higher savings lead to more liquidity for housing loans. Savings do not naturally flow into productive capital as the banks act as intermediaries and therefore will have to make a margin by on lending to borrowers. Higher savings do not lead to higher productive capital. In fact it actually bleeds from productive capital in a conservative category within a portfolio of investments.

LikeLike

National tax policy – rather out of my depth. However land tax is easier to grasp and we have it as a component of rates. My home in Auckland is values as 72.5% land and 27.5% house. I assume a similar property is a remote rural community would be 5% and 95% respectively. Services provided by council are roughly proportional to the number of inhabitants and their lifestyle so a better system would be for the National government to confiscate the component of the rates that relate to land. Where I live that would mean my rates more than tripling just to pay for Auckland council’s services but it would have little effect in rural areas. OK rather unfair to retired me but for the good of the nation and an encouragement for the high density building young people in Auckland prefer. No need for a ‘big-bang’ implementation that would penalise recent buyers with large mortgages but lets assume the government took say 5% next year and steadily increased their take year by year – easy to implement. Others can decide what to do with the money.

LikeLike

Land Tax will work as long as you have every property included in the Land Tax. It is already a failed Labour Tax policy the minute you try and exclude your own homes from the equation. The administration costs will start to exceed the revenue collection.

LikeLike

quote “you have to wonder what analysis backs up the drive for still lower rates of government debt to GDP, absolutely and relative to the rest of the advanced world”

Interesting question – this very same question has been posed by you in a round-a-bout way, either directly or indirectly within your last 3 or 4 articles.

It has been couched in terms of plans and intentions and productivity and immigration and so on – to the point I have been on the cusp of writing a response about things like strategic planning, strategic plan, the objectives, where you want to be in 5 years time and how you intend to get there, what you need to do, and milestones and reviews and did you reach those milestones and if not why not and should the strategic plan be changed in light of current circumstances etc etc etc but decided it would be too long – but funnily enough you never mention such things

In fact you have to wonder where these plans are – do they exist

LikeLike

Two small things for the TWG.

Reward saving by lowering or eliminating tax on bank deposits.

Counter this by imposing a tax on borrowings so that gearing becomes a penalty on “using other peoples money” for personal gain. That is just an extension of loss spreading to other income streams.

LikeLike

even more impressive is the government’s net worth position (per PREFU) which is essentially underpinned by current land values: why would a government implement a tax that would negatively impact its own balance sheet? in fact, stuggling to think of a country that has used tax to redistribute the housing gains from one cohort to another (especially when private debt has ballooned): probably because there is no example?

LikeLike

And why can’t NZ be the first? We have been first before with significant political decisions. There is something wrong when wealth is more a lottery than the reward for prolonged hard work and thrift.

LikeLike

My answer to that would have two strands:

1. We should really fix the problem at source – land-use regulation – rather than address symptoms with taxes. Of course, no one who has got into that pickle has done that either. Can we be first? I wish it would be so, but I’m not optimistic.

2. A land tax might well make sense if consistently applied across all land, with the proceeds “rebated” through lower income taxes. But it isn’t a slam dunk, even if one could get political weight behind applying it consistently. Why, for example, should the govt in effect force an old person with little cash income into either moving house (from a community they may have spent a lifetime in) or running up an increasingly large debt against their estate in pursuit of some elegant tax theory? There may be a good answer to that one, but I’m not sure what it is, once one puts some weight on community connections (see eg the article you sent me yesterday).

LikeLike

1) Agreed

2) Taxing all land may well cause problems but land with inhabited houses is simpler. No dramatic change (ref TOP) would be fair but just the rumour of a change to the land component of rates is likely to change perceptions and might deflate the big city property bubble. I can speak with authority about the situation of an old person with little cash income. Auckland council rates beat inflation year in year out – so although I might prefer Auckland unchanged I am paying for considerable infrastructure that I will rarely use. In other words the problem already exists.

LikeLike

Yes, and as I’ve noted elsewhere, land prices are such a large component of Akld house+land prices that altho you have capital value rating, actually it isn’t hugely different from land value rating for lots of people. (And, of course, hasn’t solved any problems.)

LikeLike

Newsflash

quote” Why, should govt force an old person with little cash income into either moving house from a community they may have spent a lifetime in, ie downsizing”

In case you weren’t following Gareth Morgan’s evolutionary ride, that’s exactly what his “Big Kahuna” set out to do

http://www.interest.co.nz/opinion/54671/opinion-gareth-morgan-fleshes-out-his-big-kahuna-idea-comprehensive-capital-tax-and

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/12712187-the-big-kahuna

LikeLike

I know. I’m not backing Gareth, and gave my tax reasons in a post late last year. https://croakingcassandra.com/2016/12/16/gareth-morgans-tax-policy/

You won’t find that particular point in the earlier post – which was just about the economics – but I have spent quite a bit of time this year trying to work thru what communities mean etc.

LikeLike

Newsflash

quote” Why, should govt force an old person with little cash income into either moving house from a community they may have spent a lifetime in, ie downsizing”

In case you weren’t following Gareth Morgan’s evolutionary ride, that’s exactly what his “Big Kahuna” set out to do

http://www.interest.co.nz/opinion/54671/opinion-gareth-morgan-fleshes-out-his-big-kahuna-idea-comprehensive-capital-tax-and

full detail here

‘https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/12712187-the-big-kahuna

LikeLike

On the topic of capital gains taxes – it seems to me that one source of capital gains that is overlooked in the policy discussion is windfall gains from drops in the neutral interest rate. This has been at least part of the story of nz capital gains over the past 15 years. If a portion of long run capital gains were due to volatility in the neutral rate, do you think this would strengthen the fairness or efficiency cases for a CGT? I agree that a GCT has many disadvantages, including double taxation of gains arising from increases in the annual income of an asset. Interested in your thoughts.

LikeLike

Which channel did you have in mind? There is the rise in bond prices as yields fall, but that is a temporary effect because the bond price has to converge to face value by maturity.

I’m more sceptical of the proposition that (say) high house prices are materially influenced by the fall in interest rates. First, interest rates are low for a reason (presumably expected future income growth rates) and second a change in interest rates should really only affect non-reproducible assets (eg unimproved land values). Of course, in some urban areas land values have risen very high – even the unimproved (but unobservable) component. But in others real house and land prices are still lower than they were 10 years ago. That suggests to me that population interacting with land use regs is more important. Of course, it is still a windfall. In principle, i have no problem with taxing it, but there are no expected revenue gains from windfalls (lose will balance gains), and a practical CGT is less attractive than a theoretical one, even in respect of windfalls (because of issues like lock-in problems).

LikeLike

Thanks Michael. Yes I don’t think volatility in the neutral interest rate makes for a strong case for a CGT, but I do think it’s been part of the explanation for NZ capital gains over the last 20 years. I’m mainly thinking of housing assets here. Even places with low population growth (like Wanganui and Gisborne) have had decent increases in their price to rent ratios (you can find the data handily on the time series page here: https://mbienz.shinyapps.io/urban-development-capacity/).

I suspect factors in addition to lower expected growth have been behind the fall in NZ’s neutral rate, perhaps some of the factors talked about in this Bank of England piece (http://voxeu.org/article/towards-global-narrative-long-term-real-interest-rates), like demographics leading to a greater preference to save. For whatever reason though, rental yields in low population growth parts of the country haven’t returned to their 1990s levels after dropping in the mid-2000s.

In the long run of course there would be no expected capital gains for asset owners from volatility in the neutral interest rate. But seeing as a real world CGT would tax gains and only provide limited deductability for losses, it might raise a bit of revenue on those rare instances where the neutral rate drops materially

LikeLike

Of course, with a trend decline in the neutral interest rate one would expect rental yields to fall nationwide. The only question is whether that occurs through lower rents (as it would in a functioning land supply market) or higher prices.

LikeLike

Sorry yes you’re right. Although it looks like only about half the rise in prices in Wanganui and Gisborne since 2002 can be explained by rents. In wanganui real rents are up 36% while real house prices are up 68%. In Gisborne rents are up 38% and prices up 80%. This suggests that falling interest rates have had a fairly large role in pushing up house prices since 2002.

LikeLike

I’d argue that it is probably the extent of land use restrictions (which often still bite even in places with limited population growth) that influences the extent to which falling interest rates are reflected in lower rents as opposed to higher house prices. after all, sharp falls in interest rates don’t seem to have raised real house prices in places like Atlanta or Houston.

LikeLike

Yes I think we’re in agreement now

LikeLike

It is not interest rates that would drive house prices because when I first bought a property, interest rates were at 18% and house prices was rising. It has more to do with liquidity and availability of credit. Liquidity can come from the accumulation of rising wages or accumulated business incomes. Of course bank credit availability also allow for higher house prices. Wheeler’s 40% equity LVR combined with China’s capital controls has dampened property market prices.

LikeLike