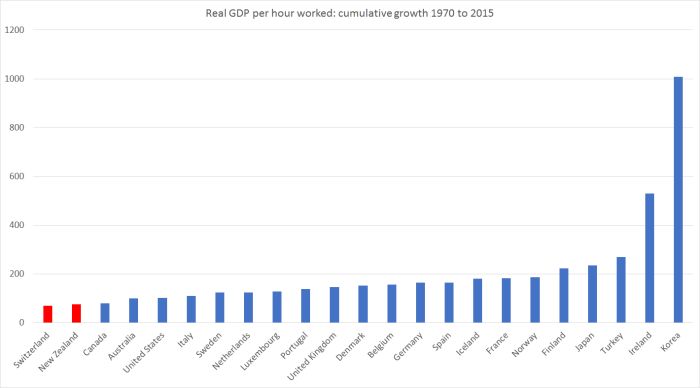

A month or so ago, prompted by a Herald news article talking up a New Zealand Initiative study tour to Switzerland to learn “the secrets of their success”, I pointed out that Switzerland wasn’t such an obvious place to look for lessons on lifting New Zealand’s continuing disappointing economic performance. After all, since 1970 they were the only OECD country to have had slower productivity growth than New Zealand

and although the average productivity level in Switzerland is still much higher than that in New Zealand, it is no longer among the very best in the OECD. Denmark, Belgium, and the United States are among the countries doing much better than Switzerland, and even they don’t top the rankings.

A few days later it turned out that the author of the article, veteran journalist Fran O’Sullivan, was actually participating in the study tour, not just talking it up. At the time, I noted that it would be interesting to hear, in due course, what she learned from Switzerland, while being a little sceptical as to how detached from a New Zealand Initiative perspective she would prove able to be.

In Saturday’s Herald, O’Sullivan devoted a substantial article to reporting back on what was learned on the tour (this time with all the appropriate disclosures, including her partial sponsorship from one of the Initiative’s member companies). Much of the article is quotes from New Zealand Initiative people. And the answer it seems, at least on O’Sullivan’s summary take, is in the headline: Education key to Swiss success.

Near the start she observes of her own past trips to Switzerland

Other times I have been to Switzerland, it has been straight to Geneva to the World Trade Organisation’s HQ for trade discussions, or to observe the World Economic Forum in Davos. Not to look at what underpins Switzerland’s own resounding economic success.

I’m still quite genuinely puzzled at where she – or the Initiative – get this idea of “resounding economic success”. I’m sure there are many things to like about Switzerland but – despite a very strong starting point a few decades ago – it just isn’t one of the great economic success stories of modern times. Productivity growth has been underwhelming – to say the least – and although GDP per capita in Switzerland is higher than in, say, France or Germany, it is so mostly because the Swiss put in a lot of hours. Average productivity is higher in France and Germany, while Switzerland is like New Zealand in that total bours worked per capita are very high in both countries.

I quite like the sound of the Swiss political system – highly decentralised, lots of quite small, and competitive local authorities. It is the antithesis of something like the Auckland “supercity” put in place a few years ago by our government. But one has to wonder quite what economic gains it might have produced. The New Zealand Initiative seems dead keen on the highly decentralised system

“Private and central bankers, economists and journalists, federal and local politicians alike – in fact everyone we talked to – agreed that this was the most crucial component to the Swiss success formula,” says NZ Initiative executive director Oliver Hartwich.

But when your country has had the weakest productivity growth in the OECD over 45 years, you have to wonder whether the alleged contribution to “economic success” is not mostly one of those myths that all countries have, that don’t necessarily line up that well with the evidence. I’m sure the decentralised system is cherished, but in modern times it has seen (although not necessarily caused) Switzerland drifting backwards.

But the political system isn’t the thrust of O’Sullivan’s article. Rather, the education and vocational training systems seem to be. In fact, even Hartwich seems to agree

Concludes Hartwich: “The most important insight was the fact that a solid vocational apprenticeship is just as respected as a university degree (and sometimes leads to better salaries, too). New Zealand businesses should not only co-operate with institutions but lead the debate on the required reforms.”

And a couple of quotes to give you the flavour of the rest

It may seem ruthless to stream students at an early level into academic and vocational education training (VET) streams. But Switzerland does just that.

About 20 per cent go into the university stream and the rest into the upper secondary school vocational education training stream, where students combine school learning with skills developed in the workplace.

This system serves 70 to 80 per cent of Swiss young people, preparing them for careers ranging from high-tech jobs to health sector roles and traditional trades. Both white collar and blue collar roles are appreciated. There are about 230 vocational categories.

and

The upshot is that Switzerland enjoys virtually full employment, the youth unemployment rate is among the lowest in developed countries and the Swiss enjoy a very high standard of living. Those doing the VET stream are not locked out from university education, which they can do at a later stage.

….

Asked if they could import one feature of Switzerland to New Zealand, the consensus of the visiting business leaders was that it would be the vocational training system.

ASB chief executive Chapman says any growing economy relies on a pipeline of skilled and motivated workers for momentum, and “in that context I think there is a lot to learn from the Swiss”.

“The Swiss have an enviable record of high youth employment.

I don’t know anything specific about the Swiss vocational training programmes, so there may well be some specific aspects that New Zealand firms, or New Zealand governments, could learn from. But as I reflected on O’Sullivan’s article, the story about education etc didn’t seem terribly convincing as an explanation of Swiss “economic success”.

Overall employment rates in New Zealand and Switzerland are very similar (on OECD data 66.2 per cent in both countries last year). But on youth employment, Switzerland does appear to have had a consistently higher employment rate. Among those aged 15 to 24, 62 per cent of Swiss were employed last year, and 54 per cent of New Zealanders.

Employment among young people is a bit of an ambiguous indicator. After all, if young people are in full-time study (school or tertiary) they often won’t be in employment at all. Youth employment rates were probably higher in both countries 100 years ago.

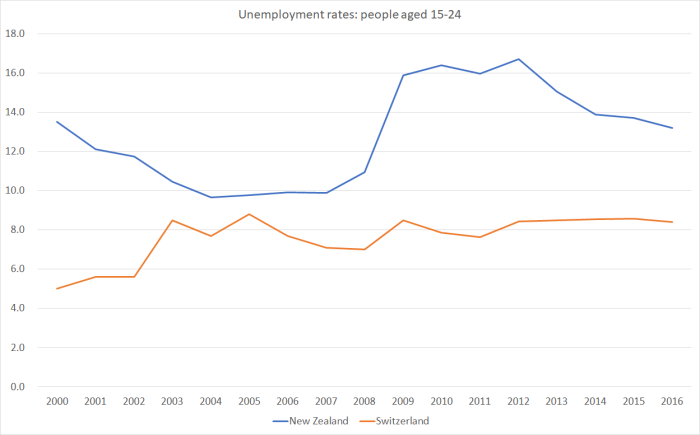

But what about youth unemployment: people who want a job, are looking for a job, but can’t find a job? Here, Switzerland seems unambiguously to do better than New Zealand.

And what are some of the things that affects the ability of young people to get into work? Minimum wage laws are likely to be one of them. I recall the New Zealand Initiative’s Eric Crampton, when he was at Canterbury University, making some very useful contributions (eg here) to the debate about the impact of the much more stringent minimum wage provisions, especially as they affect young people, that were put in place here about 10 years ago.

Readers may recall that, relatively low as New Zealand wages are, our minimum wage relative to median wages – the sort of metric relevant when thinking about whether minimum wage provisions exclude some people from employment – are very high by OECD standards (fourth highest in fact).

And what about Switzerland? Well, in Switzerland there is no minimum wage law at all. And not that long ago, Swiss voters overwhelmingly rejected an attempt to establish one. Perhaps in the course of the Initiative’s study tour no one thought to ask the question about minimum wages. But whatever the reason, it looks as though it could be a rather important omission. It isn’t the really skilled young people who typically have difficulty getting jobs, but the less skilled and more troubled ones. Our systems works against them getting established in the labour force, while the Swiss one seems not to. As the ASB chief executive put it:

“You can’t underestimate the power this has on the optimism and confidence of their youth as they look to their own future.”

But I was also a little puzzled about the story that seemed to downplay the role of universities in Switzerland. I’m as willing as next person (including New Zealand Initiative members) to think that perhaps New Zealand went through a phase where too many people went to university. And a good builder or plumber will certainly earn more than many of the occupations our more-marginal university students end up in.

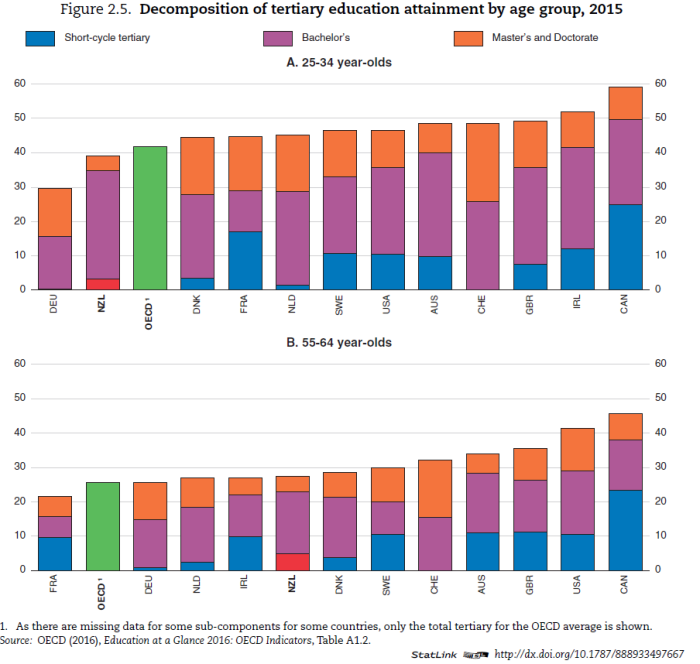

But what did the data show? As it happens, the OECD Economic Survey on New Zealand came out on Thursday, and they had a whole chapter on the labour market, skills etc. So I flicked through it looking for relevant charts. Like this one.

Switzerland is “CHE”. Relative to New Zealand – and to the OECD as a whole – Swiss young workers (25 to 34 year olds) now have a far higher rate of completed tertiary qualifications than New Zealand ones do.

And there was also this chart

Whether for younger people or older ones, Switzerland is ahead of New Zealand, particularly in the proportions with masters or doctorates.

And yet

Tertiary Education Commissioner Sir Christopher Mace says, “to be highly qualified technically rather than academically was totally acceptable in Switzerland.”

No doubt that is true – or rather I have no reason to doubt it. But a huge proportion of Swiss young people are getting strong academic qualifications.

Oh, and the OECD also makes much in their reports of the adult skills data I’ve written about here previously. Switzerland didn’t participate in that survey, but New Zealand workers came up with some of the very highest skills (notably problem-solving skills) of any of the many countries that did participate.

Still flicking through the OECD chapter, I found another interesting chart on employment. Ideally it would be a chart of all sole parents, not just mothers, but it was part of another chart focused on maternal employment.

Switzerland is at the far right end of the chart.

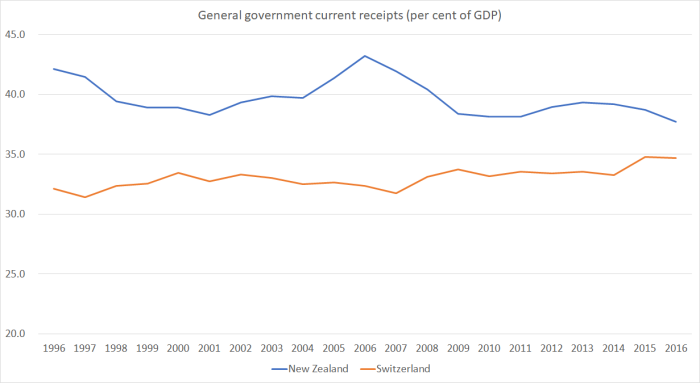

Which is by way of leading into another difference between Switzerland and New Zealand – the overall size of government is a bit smaller there. Here is the OECD data on current government receipts (mostly taxes) as a per cent of GDP.

The Swiss tax take is smaller than ours, as a share of GDP, but (a) the gap seems to have been closing, and (b) at least as much of that is coming from the Swiss raising average taxes as from us lowering them. Again, if one is concerned about productivity, it isn’t obvious that the Swiss experience has a great deal that is positive to teach us, even if the reasons for their weak productivity growth might well be different from the reasons for our own.

The Swiss track record with weak productivity growth isn’t something new that no one had noticed before – the OECD, for example, has been offering thoughts on it for some time (eg here). So it is still a bit of a mystery why the New Zealand Initiative is touting Switzerland as a success story to emulate, or why a senior journalist is channelling those lines. Perhaps it would have offended New Zealand business leaders’ sense of amour propre to have gone further east, but if there are many lesssons to be learned for us in Europe about lifting overall economic performance, it seems more likely they might be found in countries like Slovakia or Slovenia, Estonia or Latvia (all now fellow members of the OECD) where productivity is fast catching up (in some cases already has) average levels in New Zealand – and that in countries that for the whole of modern New Zealand history (ie since say 1840) have been much much poorer and less productive than New Zealand.

Travel generally broadens the mind, and almost any country can probably offers some experiences (good and bad) that visitors could learn from. I’ve no doubt Switzerland does too (eg about minimum wages and company tax rates perhaps) . But Switzerland’s overall economic growth performance has been poor for decades, and that even with the advantages that come from being a relatively-small government place in the heart of one of the most prosperous places on the planet (northern Europe). It seems unlikely there is very much to learn from them, at least in a positive sense, about how to markedly lift the performance of another struggling country almost as far from anywhere (and from suppliers, markets, clusters of knowledge) as it is possible to be.

One could wonder whether this group of leading business people, (having gone off to learn from Switzerland, where they would have found a system with no minimum wages and much lower company tax rates, but nonetheless want to tell a story about training and education as the secrets of what they see as Swiss success) are not perhaps preparing against the chance of a change of government later in the year. All that talk in the article would, no doubt, have seemed like music to Grant Robertson’s ears. Perhaps not, but I’m struggling to formulate a better hypothesis. Because the data don’t really seem to fit their story.

My own general knowledge of Switzerland was that it used to be the Financial Hub of Europe and international money launderer of the worlds hot money. It was a neutral zone during WW11 and a place of rest and recreation for German officers and a store of of Nazi stolen wealth. Its productivity decline in recent decades probably aligns with its now transparent banking sector under global pressure from Anti Money Laundering activities and its decline as the Global recipient of hot money and repatriation of stolen Nazi wealth to aggrieved nations. Not exactly the best example for NZ.

LikeLike

Geography has a lot to do with it. A lot of the richest parts of Europe are along the rivers Rhine and Po. http://econlog.econlib.org/archives/2016/05/the_rich_heart.html

Not knocking it. In terms of places to live and work, I would put Switzerland at the very top.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree re the significance of geography (to them but also to us)

Mostly I’m sure it is a great place to live, altho I still rankle at the story i was told when on a course there, about local government restrictions on when one could or couldn’t mow one’s lawn.

LikeLike

Michael, I missed your earlier comments.

You will find it is commonplace in media reports for the disclosure of any assistance with trips to come in reports emerging from the visit. Not in a short preview story.

You earlier wrote: “One presumes NZME is paying for her to undertake the tour, but even so. Wouldn’t it normally be elementary to let readers know of your involvement when you write up the story?”

As I disclosed in a piece last Saturday, Air NZ assisted me with flights to get to Switzerland. What you chose to overlook in my disclosure was the fact that I had personally paid the programme fee. For the record this was about $9000 all up. Perhaps this did not fit your unfortunately snide insinuation?

LikeLike

Thanks Fran. I had assumed that the cost of the programme was greater than the cost of the airfare (given that costs in Switzerland are very high), and thought that was covered by the “partial sponsorship” comment.

LikeLike

Michael, the disclosure is clear.

Fran O’Sullivan funded her programme fee for the NZ Initiative’s Go Swiss study tour and received assistance from national flag carrier Air New Zealand to fly to Switzerland.

The programme fee included internal travel, meals and accommodation – among other costs.

I could have given further clarification if you had done me the courtesy (first) of calling me before bursting into print.

But again – that may not have fitted with your assumptions.

LikeLike

Sorry, I didn’t think my last comment was particularly disagreeing with anything you said. I took the disclosure at face value, wasn’t trying to misrepresent it, and what you’ve said since is roughly what I’d have expected.

I am uneasy about journalists and media outlets getting too close to those they report on, and taking partial sponsorship is a part of that. But it is probably the established way of the world in New Zealand, and to some extent “inevitable” given the small size of the country. We presumably have different views on the merits/risks of such practices and that is fine – the issue around partial sponsorship isn’t exactly central to this or the previous post. I’m sure the views you run are (when quoted) those of Initiative members, and otherwise your own considered reflections. And my bigger concern – surely apparent in these posts – is the problems with the prior assumption (Swiss resounding economic success, and whether there are lessons for us) rather than with the risks of a journalist getting to close to lobby groups.

LikeLike

Fran – any thoughts on the actual substance of the commentary though? Michael has identified some pretty clear themes out of the data suggesting the conclusions from the ‘tour’ are somewhat (considerably?) off the mark…

If NZ can’t replicate the historic/geographic advantages that led to Switzerland’s high relative wealth, why should we now be trying to emulate the strategies and policies that have subsequently led to the poorest productivity performance in the OECD?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think it’s pretty simple. Countries that have a lot of large, external-facing corporations, tend to have high incomes. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Swiss_companies_by_revenue

LikeLike

I had forgotten that ABB when it merged had moved its head office to Switzerland. Now that is a huge Automation and infrastructure company. Even Rockwell USA does not compare in size to ABB. In NZ, ABB trades upwards from $120 million per annum compared to Rockwell NZ that does about $40 million and those numbers are from 20 years ago when I had worked for both companies in succession.

LikeLike

I recall Rockwell used to sell lots of Automation and industrial equipment to Carter Holt Harvey and ABB could not crack that market. So ABB came and offered a complete outsource solution by taking over the entire engineering division of CHH and changing all the equipment towards a ABB standard.

LikeLike

Revenue of the top 2 companies alone exceeds NZ’s GDP

LikeLike

In 2005, Fran O’Sullivan was gushing over John Key’s praise for the “Irish miracle” that quickly turned into an “Irish mirage,” then an “Irish debacle.” Now the same writer followed Key’s line again, this time with Switzerland as the object of our desire.

Two points seem obvious to me about such an approach to business journalism.

The first is that I am extremely sceptical of any attempts to present any particular country as an example New Zealand should emulate. This is because, to state the obvious, all countries are different, and perhaps no countries within the OECD bear direct comparison with New Zealand, and that includes Australia. In particular, as Michael points out, Ireland and Switzerland are well established countries in close proximity to the huge economy of Europe, while we are still a relatively young, small economy and isolated, thus very much subject to the gravity theory of trade.

My second point is that writers like O’Sullivan should be astute enough to invoke a “sniff test” on the promoters of such adulation of carefully selected examples. The NZI, while I accept they strive for independence, nevertheless inevitably approach these issues from a particular ideological perspective (no criticism implied, we all do). Examples like Switzerland, Ireland and, indeed, like the oft-praised authoritarian Singapore (a favourite of Don Brash at one stage) often turn out to have scant direct relevance to New Zealand.

I worry at the tendency for some writers to adopt such an uncritical tone, especially when “embedded” with the promoters.

I would love to see such articles from business journalists that adopt at least a stance of reserving judgement, or even consciously critical, while laying out the evidence for readers to judge for themselves.

And I was surprised that this high-powered group and senior journalist arrived in a comparable country with no minimum wage and relatively low youth unemployment, and did not dig into the fiscal, education and/or cultural paradigm that allows this to work without having disaffected youths sleeping under bridges. After all, we have the latter situation even with a minimum wage! Even parts of the U.S. is making baby steps towards a more generous minimum wage, so Switzerland is in pretty stark contrast to the rest of the OECD, and it would be truly interesting to know more.

So this reader would like to see more work by these journalists at that level of bottom-up analysis rather than the broad brush “vision thing” (I think I’ve borrowed that from Muldoon) that so often comes to nothing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fran is not an Ambrose Evans-Pritchard and never will be.

LikeLike

Luc: Fair points.

But re Ireland – what the Key interview focused on was the tax structure to secure MCN/employment.

That was not at the heart of the banking crisis.

LikeLike

Thank you, Fran.

Apologies for conflating your article with Key’s more general public praise of what was then still the Irish miracle.

LikeLike

If I understand it correctly your “graph of employment rates of lone parents -v- partnered mothers” is only showing lone parents and the fact that in Switzerland they are usually working. They could be teenage single mothers or maybe in their fifties recently widowed or divorced. It would be interesting to know more since the experts say two parents in a stable relationship is the single most significant factor in whether a child becomes a successful adult (mental health, addiction, crime, education attainment, divorce and those kind of measures).

I remember reading a few years ago that Switzerland has roughly half the ratio of teenage single mothers as other European countries. The reason given being application for benefits was from the canton; asking your neighbours for charity is a disincentive.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, you are reading that (part of the) chart correctly.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Lindt v Whittakers? To close to call: I’ll take both….

LikeLike

To Blair’s point, market cap for Lindt around $22bn NZD

Whittakers??? Not so much. (although i was recently behind an Australian woman in my local suburban supermarket checkout queue, who was buying up substantial quantities of Whittakers chocolate to take back to Aus as “superior to anything on offer at home”)

LikeLike

Just a note on minimum wage and tertiary education in Switzerland.

At least half of employees are covered by a minimum wage via Gesamtarbeitsverträge (i.e. collective contracts between trade unions and employers’ organisations) or Normalarbeitsverträge (i.e. laws by the federal government for certain sectors, e.g. retail, domestic workers).

The tertiary education sector includes vocational qualifications. There are schools/exams which offer higher education specifically for those who have completed vocational training. People start working or get practical experience early on and can then specialise or prepare for leadership positions through these schools/exams. Their share of the total tertiary sector has declined from 50% in 2005 to a third in 2015. So a substantial proportion of those with tertiary qualification has gone through the vocational training track/stream.

I’m biased since I’m originally from Austria which has a similar system, but I’m a strong supporter of streaming and the dual education system. Ideally in my view we’d want to confer skills to most young people while also giving them the opportunity to get higher qualifications later.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks. That is useful information.

LikeLike

If Austria were your home instead of New Zealand you would…

be 23.44% less likely to be unemployed

make 40.13% more money

have 8.44% more free time

be 48.44% less likely to be in prison

experience 27.35% less of a class divide

all that and it is a beautiful country judging by a day trip to Salzburg. Do they have a spare economist for the RBNZ.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Takes me back to my young days when the schooling did just that. e.g. Hutt valley High school, basically academic but with some practical as well. Petone Tech where the trades were the focus.

But apparently the educators and the Unions knew better and so that went out the back door. There is now some moves to restore the order of things to how the world should be.

Learning is life long. Don’t think so, just look around at all the oldies and not quite so old who can use computers and write code etc. All come about just lately and long long after we all left the clutches of the education controllers.

LikeLike

Really – don’t know where you get that from

I was writing code in IBM assembler and Cobol for IBM mainframes in 1960’s and 1970’s, then Super-minis 1970’s and 1980’s

LikeLike

iconoclast

June 19, 2017 at 7:53 pm

Really – don’t know where you get that from

I was writing code in IBM assembler and Cobol for IBM mainframes in 1960’s and 1970’s, then Super-minis 1970’s and 1980’s

You might well have been but you were certainly not mainstream if you were. Unlike todays kids who are learning this stuff in Primary school. The 60’s IBM’s could do what my cellphone does now.

The reality is that most people never got to play with nor own a computer until the very late 80’s and early 90’s.

LikeLike

Call me cynical but nothing I have read from Fran or the Initiative is news and nothing it seems that could not have been deduced from a desk top right here. No need to rack up carbon miles and waste so much money unless of course it was another “old boys/girls ” trip.

Ego driven it would seem. Laziness really when all the info is at the touch of a keyboard or does this actually make the point that education is the key? Being educated in the use of google and a few searches and spreadsheets.

Watched Harwich on Q+A on Sunday. Totally unimpressed. Has old ideas trotted out in a very Dutch or German way. Control , control, control.

Don’t think we should give much credence to his work.

It still amuses or perhaps perplexes me why we need to rish off and look at other countries bad habits when we have plenty of open minded people and people with exciting minds and idea’s that we never harness. Copying Britain, Germany, France or whoever means we just get the worst of the deal.

We need to develop our own way of doing stuff.

That’s what we are being told to do by those supposedly in charge. Unfortunately they don’t listen to those of us in the real NZ. Youth rates are probably the foremost example.

Minimum rates were always going to be a disaster, especially for young men, keeping kids at school when they needed workplace places is a disaster for them (Lack of mentors at a young age for many),fitting students up with loans to go to prop up many broken down teachers (especially tradie retards), is another disaster for youth. (As bad or worse than the current scam with immigrants, who clearly keep wage rates down by being here),

But no matter what noise we made the Nice Mr Key was only intent on pandering to the voters who would keep him elected.

I doubt the National Party will ever be other than socialist for ever more.

LikeLike

Disagree – to get a decent feel for a country you have to go there and converse with locals. Of course that applies to the Brits like myself whereas most educated Kiwis have been on OE’s and as a friend who spent a decade travelling all over the world told me it didn’t matter how remote a place you went to you could be sure of meeting another Kiwi there.

Will anyone propose the obvious solution on how to give NZ all the advantages that the Swiss have: close half our the universities. My suggestion AUT and University of Auckland – that would also solve Auckland’s housing and transport problems. Other advantages is several billion in property and land; kids at college trying much harder to attain uni entry which might make them less ignorant; smarter manual workers; no disgruntled graduate secretaries/receptionists.

Reminder lets catch up with Switzerland and be

be 50% less likely to be unemployed,

make 80.26% more money,

spend 2.7 times more money on health care,

have 11.11% more free time,

be 56.25% less likely to be in prison,

experience 20.72% less of a class divide,

live 1.46 years longer .

LikeLike

Hi Michael

I just ed wanted to refer to my paper Education and Labour Productivity in New Zealand, 2010, Applied Economics Letters Vol. 17, issue 2, 169-173, which was published online in 22 April 2008, where we (with Jason Timmins) found no association between the stock of labour with vocational skills and productivity.

Most of the gains come from University and higher education in NZ and the product of university and higher education with R&D.

We can have as many plumbers, electricians and car mechanics as one can, but productivity is not going to increase. This is not how productivity increases.

Education is one factor among many. Education speeds up the diffusion of NEW technology. I cannot see how vocational training do that!

LikeLike

Thanks Weshah – that useful. Of course, we still need good plumbers and builders, and they can expect to earn pretty well,

LikeLike

I remain skeptical of university education. If a university is a machine that takes in teenagers and churns out thoughtful adults then much depends on the quality going in. Certainly there are students who do poorly at school who shine at university but they are rare. What it does do is delay starting work. Is it a coincidence that I have meet 4 programmers who I will admit to being better than me (I mean on their average day they were better than me at my best) and none of them went to university – programming is like playing a musical instrument: the earlier you start the better.

The argument that university education is the super cure for the economy is true for maybe the first 5% but becomes less true as dumber people enter the system. Politicians such as Mrs Clinton assert that a university education is worth a million dollars because that is how much a graduate earns in a lifetime in excess of a non-graduate. Nobody believes sending every child to university makes sense. There has to be a cut off point and it seems as if Switzerland has it about right. Note they may have some far brighter plumbers than us and some of them will move on to university. A combination of practical and abstract thinking may be the solution to increasing our productivity..

LikeLike

ABB is a Automation and infrastructure giant with a CHC91 billion or NZD130 billion in sales. These guys build factory robots. Not sure why productivity would be so low in Switzerland?

LikeLiked by 1 person

The constant refrain of Productivity

Can you please explain which is the more productive and when does the increase occur

A drainlayer employs 10 manual ditch-diggers in 8 hour days to dig ditches

Another drainlayer purchases a $75,000 digger and employs 1 digger driver to dig the same amount of trenches

LikeLike

If one thinks in terms of labour productivity, your second example involves greater productivity. And it frees up 9 people to do other stuff. If one thinks of GDP per hour worked, the increase occurs when the change in production patterns occurs. There is an implicit assumption that the displaced workers are in time re-employed elsewhere, as they have been now through a couple of hundred years of technological change etc.

In terms of total factor productivity it isn’t possible to answer the question with the information provided.

LikeLike

Except that if those 9 end up being on the dole then productivity goes way down as the one doesn’t earn enough and pay enough tax to keep the 9.

And there’s the problem. You can replace men with machines and total. Productivity goes up for the remaining staff but if we just shift that 5 to another job productivity only improves if the displaced can produce enough to at least cover the work they previously did. If they don’t then total productivity goes down. Conversely if they are employed in a more productive job then productivity goes up.

Productivity also only goes up after the cost of capital etc. is accounted for otherwise you might as well not bother (other benefits excepted.)

LikeLike

Needs an edit function please.

LikeLike

Profit only goes up after the cost of capital is accounted for, but productivity is something different.

Recall the concerns all the way back to the Industrial Revolution about technology destroying jobs. Of course, at one level it did, but in time – sometimes very quickly – those people were reabsorbed in other roles. At least on average, the new roles paid more than those that had gone before. Thus, our material living standards are so much higher now than they were 200 years ago.

Of course, not every individual is better off through the adjustment phase, and there are reasonable arguments for public support for such individuals – the price, if you like, of allowing overall living standards to improve.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Productivity went up because those displaced workers just begged on streets and therefore did not count in to productivity as they are now in social welfare. Also poor people die relatively early which means that if you lose your job around age 45, you might just be unproductive for 5 years before you die from poverty begging on streets. Therefore within 5 to 10 years of a industrial revolution displaced workers just die and disappear from the statistics.

LikeLike

One should be disturbed by this junket to Switzerland by a bunch of captains of industry

Education is not a tangible thing that one can observe, touch, feel, assess and evaluate. And also if these captains of industry were to arrive at the same conclusion as Fran O’Sullivan then the question arises as to what they can now do about it – nothing

The whole thing seems to be a waste of time at the same time as placing a question mark over the smarts of these captains of industry, unless of course it was just a cover for a conducted junket overseas

As I pointed out above, the income of the top two largest Swiss companies is greater than the GDP of NZ, that should have been a warning in itself – they could have simply visited those two companies alone

LikeLike

The question is how did their companies manage to get so big? I think it fundamentally boils down to a large domestic market, a large work force, a large capital market and lower cost of funds which still means more people rather than less. Our problem is we have NZ economists that are of the strange opinion that a cow is more productive than a person. A cow that eats and create unmanaged waste to the equivalent of 20 people is more productive than a person. 10 million cows that eat and create unmanaged waste that is equivalent to 200 million people and create only $13 billion in GDP is more productive than 1.5 million people in Auckland that create $75 billion in GDP.

Of course if you compare a company like ABB that employs 130,000 workers but generates sales of $130 billion then of course our 1.5 million Aucklanders can’t quite compete in the productivity stakes.

But the first mind set problem we need to solve is to stop the idea that a cow is more productive than a person.

LikeLike