The OECD released today its biennial Economic Survey of New Zealand. I will write about it in due course, but there are 170 pages to read.

Usually these reports are just released on the website from Paris. But today the OECD’s Chief Economist, Catherine Mann was in town, to help promote the OECD’s view of the world. There was a press do this morning apparently, and then a Treasury guest lecture presentation, attended by all manner of past and present bureaucrats, and some others with an interest in what Catherine Mann had to say.

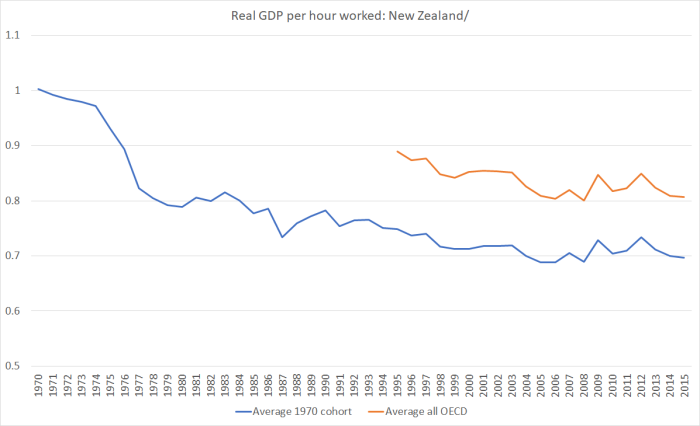

She gave us some brief observations on the state of the world economy, before turning to present the New Zealand survey – the OECD’s story about what is going on here, and what should be done to make things better. To their credit, the OECD is quite open about the ongoing severe underperformance of the New Zealand economy – as they note, the productivity gaps to the richer OECD countries are large and, if anything, are getting larger. Here was my variant (from a post last week) of the sort of chart she showed.

But the point of this post is about the bit where she took my breath away. I couldn’t quite believe what I was hearing. I don’t think even the Minister of Finance or the Prime Minister would have made such bold – but unsupportable – claims.

She presented a chart showing growth in real GDP per capita in the OECD as a whole in the US, the euro area, and in New Zealand. As she noted, growth in all regions is still lower than it was in the 20 years or so prior to the 2008/09 recession. In the other three regions, the OECD is picking that per capita GDP growth will pick up in 2017 and 2018, but in New Zealand they are picking it to slow a bit. I looked at the chart and didn’t make much of it – there is plenty of year-to-year volality, and I wouldn’t put much weight on just two years’ data.

But Mann couldn’t help herself. She was here to tell a good news story, and proceeded to try to do so. You might, she said, look at that chart and think it wasn’t a very good story for New Zealand – real per capita growth was picked to slow after all – but, no, in fact it was really a good thing. Perhaps, I thought, she was going to say that the economy was overheating and needed to level out. But it was a bigger bolder claim even than that.

Her argument was that per capita growth was just slowing “mechanically” because we’d acquired so many more people, and were forecast to keep on doing so. Of course, she said – advancing no story for why – this would weaken per capita GDP “arithmetically” in the short-term. But – and here I scurried to write down as much as possible her actual words – because we were taking in so many more people to work and study, who would add value, bring fresh ideas, and create new businesses we were creating the underpinnings of a longer-term stronger economy.

Apparently, high levels of immigration were now bad for per capita income in the short-term, but would be good in the long run. It was pretty much the opposite of the conventional New Zealand evidence – that demand effects exceed supply effects in the short-term. But set even that to one side for the moment.

[UPDATE: On reflection, perhaps she had in mind some of the European countries with waves of refugees crossing borders, adding to population and probably not doing much for economic activity in the very short run. But that is nothing like New Zealand’s immigration system – most people arriving either have a job to go to, or are paying for a course of study about to begin.]

Because, in fact, she reckoned she had evidence that we were already seeing significant benefits. And what form did these benefits take, in the assessment of the chief economist of one of the world’s premier international economic agencies? Why, it was wage increases.

She had another chart, showing real wage growth for the US, the euro area, and New Zealand. On this measure, real wages had been rising strongly in New Zealand in the last two years – more strongly than the average for the 20 years prior to the recession. (And over the same earlier 20 years New Zealand had had the lowest average real wage increases of any of the regions she showed). And what was her story to explain this? Why, it was the immigrants. We were bringing in highly skilled immigrants, who will be earning higher wages, and – look at the chart – we see it in the data already.

Many of you will no doubt be wondering about this alternative universe. But it is real data. And, in fairness, comparing wage increases across countries is quite difficult, because countries measure things different ways. In this case, she used a measure of “labour compensation per employee, adjusted for the GDP deflator”. Ideally, one would want to use wages per hour worked, rather than per employee, but set that to one side for now. More importantly, in commodity exporting countries – where the GDP deflator (value of the stuff produced here) inflation rate goes all over the place, no one but no one thinks that the GDP deflator is a meaningful statistic to use to deflate anything year to year. When dairy prices plummet, on that measure real wage inflation rises, and vice versa. From year to year, it tells one nothing meaningful. And this, recall, was a presentation specifically focused on New Zealand.

Here’s an alternative – much better – measure of real wage inflation for New Zealand. It uses the private sector LCI (analytical unadjusted measure) adjusted for the Reserve Bank’s preferred measure of core inflation, the sectoral factor model. There is some short-term variability, so I’ve used annual average increases.

Not much sign of the recent high rates of wage inflation the OECD’s chief economist was touting. The QES – an actual compensation measure – is even weaker.

Of course, there isn’t much sign of the really highly-skilled migrants either. Mann seemed to have forgotten that the OECD skills data – which they use quite a bit in this report – shows that while New Zealand’s immigrants are relatively highly-skilled compared to migrants to other countries, they are on average less highly-skilled than the natives. There hasn’t been a sudden change in immigration policy in the last couple of years that has generated some step-change increase in the skill level of migrants.

A sceptic sitting near me whispered, “just drink the Kool-Aid Mike”……

I was puzzled by all this, and waited for the question time at the end of her presentation. I asked Mann quite what her optimistic take was based on – that while immigration would apparently be denting per capita GDP now, it would soon lead to an acceleration. After all, I noted, we’d had large immigration inflows for decades, and on the numbers she had presented we’d had the lowest productivity growth and lowest real per capita GDP of the countries she had shown. I wondered if she could explain her optimism in terms that took account of New Zealand’s experience over the previous 30 years or so (not my chosen period, but the one she was using in her own presentation).

It was a pretty astonishing response. She argued that this was an “immigration-driven economy”, and asserted that the skill characteristics of the immigrants were high, repeating that the evidence for this was the high real wage increases we’d seen in the last couple of years. Moreover, she asserted, the pre-recession period wasn’t that relevant because we had so many more immigrants now (and presumably could therefore expect much larger future real economic gains). She seemed not to be aware at all that the largest single component of the increase in the net PLT inflow had been the reduction in the number of New Zealanders leaving. Or that the new analytical immigration data suggested there wasn’t anything very exceptional about the inflows of non-citizens we are seeing now (there was something similar 15 years ago). Was she aware that there had been no increase in the residence approvals targets – indeed a cut more recently – and that a significant chunk of the rest of the increase in the net inflow wasn’t more people chosen for their high skills, but (eg ) working holidaymakers and students mostly studying in relatively low-level courses. It was a quite extraordinary degree of ignorance in someone holding forth so confidently on the undoubted gains New Zealand would see from the large immigration flows. I don’t expect the chief economist of the OECD to be across all the details of New Zealand (a rather small and minor member of the OECD), but if she isn’t, she shouldn’t be holding forth with such breezy confidence on such a major issue of New Zealand economic policy and economic performance. Instead, she seemed to have a doctrine, and patched together something that superficially appeared to make the data fit the doctrine.

It went on, because she attempted to explain away why our real wage inflation had been less than that of the US or the euro-area in the couple of decades prior to the recession. It was, she claimed, because the historical US numbers were (somehow – it wasn’t made clear how) biased upwards, and the New Zealand numbers were biased downwards. Perhaps, but it was a new claim on me, and not one for which there was a shred of evidence produced.

It was an astonishing performance. She then invited the OECD’s desk officer for New Zealand to add any comments. I felt a little sorry for him – especially as he was an old friend of mine. He noted that the actual slowdown in real per capita GDP growth the OECD was picking for this year and next was mostly to do with them using the expenditure measure of GDP, and the gap that had opened up between the expenditure and production measures (ie just technical stuff). He certainly wasn’t running an immigration story for that, as Mann had attempted to do.

He (who knows my story reasonably well) went bravely on attempting to address my question about how this optimism about the economic effects of immigration fitted against the backdrop of the last 30 years. But it was clear that neither he, nor the institution, had any sort of narrative explanation that would even begin to fit the bill. He seemed reduced to quoting the recent IMF cross-country empirical piece on immigration. As he noted, in that sample (which included New Zealand as one of 14 countries), immigration did appear to have boosted per capita GDP. But, as I pointed out in a post when the work was published even if that result was true on average for all the countries in the sample, there was no reason to be confident it had been so over this period for New Zealand (since these are average results). More importantly, perhaps, the same study actually found negative effects (although not statistically significant) of immigration on both labour productivity and total factor productivity – again, on average across this sample of countries.

I’ve seen quite a few leading international economic agency senior officials in my time. This was one of the worst performances from such a senior person I’ve ever seen. She may well have been quite good in her own area – international economics – and in fact I went along mostly because she had a very good academic reputation, and had performed well when I’d seen her previously. But when she lapsed into advocacy and cheerleading for New Zealand’s immigration policy, without getting fully familiar with a credible story that fits the New Zealand data and experience, she probably did herself, and the cause, more harm than good.

[UPDATE: For anyone interested, her presentation slides – including the charts I tried above to describe – are here. ]

someone needs to explain growth accounting to these people. Adding inputs – be it capital (as National did under ‘Think Big’) or labour (as National is currently doing, doesn’t necessarily have any impact on total factor productivity. It creates the illusion of growth, nothing more. Policymakers should be focussed on how to boost TFP.

LikeLike

In fairness to the OECD, they are whole-hearted TFPers. But their model of the world is one in which immigration lifts TFP so when they turn to NZ it is simply a case of “have faith, rub the magic lamp, and all this immigration will in time produce the TFP”.

All this despite being an organisation that five years or so published a nice paper showing that their models couldn’t explain NZ’s underperformance remotely well.

It was quite striking – but not at all surprising – that in her presentation yesterday there was no mention of the real exchange rate, and only the merest hint of noting that our real interest rates have been above those in the rest of the advanced world for decades.

LikeLike

Peter, when a cow eats and generates unmanaged waste to the equivalent of 20 people, the Labour component of your growth accounting is clearly wrong. With 10 million cows that is the equivalent of feeding and handling waste of 200 million people, the GDP of $12 billion of milk and meat generated looks extremely sickly compared to the $75 billion in GDP generated by 1.5 million people in Auckland.

LikeLike

New Zealand has agreed to cut greenhouse gas emissions further as part of a new global Paris agreement.

“Agriculture produced 45% of all emissions by industry in the 5 year period of the rst CP, yet it had no direct financial obligations. This placed the financial burden of reducing emissions on the other half of emitters, and the costs of growing emissions from agriculture on the taxpayer.”

Click to access The-Paris-Agreement-February-2016.pdf

The Paris Agreement will likely cost New Zealand tax payers $1.4 billion a year of which 45% carbon dioxide pollution is due to the Agricultural industry. Methane gas was not included which means that if it was included NZ would have stood right beside Trump in not signing the Paris Agreement

LikeLike

Stuff reported that mediocre management was part of our problem. Perhaps mediocre economists could be added to that.

LikeLike

Our decline started when our NZ economists decided that a cow was more productive than a human being.

LikeLike

I think it was her on Mike “I’m the definition of Kool Aid” Hosking this morning. Apparently the productivity issue is simply because people with skills can’t move to areas that need their skills (and therefore earn more) due to a lack of housing. I assume this refers mostly to Auckland where average wages are higher.

So the universal solution (a true miracle elixir that will cure all) is to simply build more houses. Oh, which of course requires importing a bunch of building labour…

But then I’m really confused about the whole chickeney-eggy thing. We take in high levels of immigration, most of whom end up in Auckland. This creates a housing shortage given we don’t build enough to meet the demand. We then claim we need to push these people out into the regions. Where apparently there are highly skilled people who are underpaid who need to move to Auckland to be paid more and solve our productivity/wage issue. But they can’t because Auckland is gummed up with homeless immigrants.

So really the whole policy can apparently be boiled down to a concerted effort over multiple governments to depress wages not only in Auckland (where immigrants get trapped) but also the regions (where highly skilled people who should be in Auckland are trapped). And in parallel try to create asset inflation (benefiting mostly those that owned housed early or inherited them) and massive household debt accumulation (for the rest trying to get ahead in a low wage environment) via a mismatch between housing demand and supply?

Feels like even the OECD has fallen into the believing in the bizzaro world of New Ponziland…

LikeLike

I think they largely have a standard model, which may often work reasonably well. It is most evident in their beliefs around immigration, where they seem reluctant to confront the specifics of NZ’s actual experience. Until I’ve read the report in detail, I’m reluctant to be too critical, but in my observation so far they’ve always been reluctant (for example) to engage with the data that show that whereas in (say) London GDP per capita is far far higher than in the rest of the UK (making a strong case for more people), in NZ Akld’s GDP per capita isn’t that much above that in the rest of the country and indeed that gap has been narrowing. One possible interpretation – not perhaps the only one – is that, if anything, too many have come to Auckland, and the opportunities there just aren’t great. In what is still a highly natural resource based economy, that wouldn’t be a particularly surprising conclusion.

LikeLike

I think once most economists outside of NZ become more aware of our 10 million cows and 30 million sheep which distorts our rural GDP per capita compared to Auckland they would recalculate livestock as being more productive than people.Common sense would tell you a cow is never more productive than a person.

LikeLike

Your “chickeney-eggy” paragraph is a joy. It may be worth considering immigrants intentions; I read somewhere the fact that immigrants prefer to move to big cities was discovered by sociologists a hundred years ago. Fairly easy to see why: better chance of meeting others of your own kind, usually better work opportunities and of course a foreigner will have some knowledge of Auckland but little idea of life in say Dargaville or the thousands of equivalent small towns.

From conversations with immigrants taking our major sources of residents as India, China, Philippines, UK, South Africa then the immigrants from the first three share an ambition to own detached house on its own freehold section. So given time Auckland will be a mix of apartments inhabited by native Kiwis surrounded by traditional housing inhabited by first and second generation immigrants.

LikeLike

Surprisingly, after 4 weeks of trialing out Air BnB. I finally decided to rent out my 45sqm Mt Eden apartment to weekly tenants as the cleaning costs was a little to much effort. Surprisingly my new tenants are from the UK. One British lady is relocating from Sydney to Auckland to join an Scottish engineer and a British chef. It is excellent that I can help prop up the pakeha Crown British faction of the biparty Treaty of Waitangi. In other words, there are only 2 ruling parties allowed under the Treaty of Waitangi, Pakeha Crown British or Maori. Too many Asian migration is watering down pakeha Crown British majority to the benefit of Maori. I am starting to think this high influx of Asian migration is a conspiracy driven by Maori leadership to water down pakeha dominance in government.

LikeLike

True Believer – chuckle – reminds me of this snippet

missionaries and fanatics

In the deep south a revivalist meeting is in progress. A charismatic evangelist fires up the congregation with fire and brimstone. Many see the “light” and become immediate devotees. In a state of heightened fervour, the congregation contribute generously as the collection plate is passed around.

chartists and fanatics

In the far north, a charting seminar is in progress. A charismatic presenter fires up the congregation with promises of untold wealth and riches. Novices learn charting is the light and the way. Convinced they have found salvation and the holy grail. In a state of heightened expectation the congregation contribute generously. Signing on for the never-ending journey to “el-dorado” and “valhalla”.

LikeLike

Question

Does the OECD always send out a charismatic envangelising presenter – or is this a first

LikeLike

It is quite unusual – i was quite involved with the NZ side of these surveys for a long time, and have never seen a launch like this. of course, senior OECD officials do come thru for other reasons from time to time.

LikeLike

As I suspected

which runs the risk of being characterised as a “by invitation” of the current government

LikeLike

possibly, altho her presence is a bit of a mixed blessing. most of the pro-productivity reforms they are calling for, the govt has no intention of doing, and they don’t really welcome having the dismal productivity performance highlighted by a senior international official in public

I suspect it was prob some mix. Mann was probably keen to get around the members – as she said, it was a long time since she had been to NZ, and it mostly rained then – and perhaps someone (whether in Wgtn or Paris) suggested that the release of the Survey wouldn’t be a bad occasion/opportunity. And in many ways, it is a good opportunity – it was just a shame that her presentation got so gung-ho with so little apparently to support it.

LikeLike

Seems from the presentation NZ tertiary education attainment is below average (slide 13) but NZers have high problem-solving skills in ‘tech rich’ environments (12) while being overqualified for their jobs (14) which are increasingly shifting to ‘high-skilled occupations’ (10), yet, productivity growth has been relatively poor (7). Well-bring is high (slide 1) though which is obvious given the former observations….

LikeLike

Thanks. I’ve now included the link to the slides – i didn’t realise they had put them online.

LikeLike

[…] think many of these results don’t stand up to close scrutiny (eg on the IMF here, or the OECD here), or may not have much application to a single extraordinarily-remote location, but they neither […]

LikeLike