I went along yesterday to a Treasury guest lecture, to hear from one of great figures in the history of New Zealand economic policymaking, Sir Roger Douglas, and his co-author Auckland University economics professor Robert MacCulloch. Their presentation was based on a recent paper proposing a wholesale reshaping of New Zealand’s tax and welfare system. I’ll get back to that.

Roger Douglas is 79 now, and if his voice is weaker than it was once way, his passion for a better New Zealand is as clear as ever. In his brief remarks, there was more evidence of a passionate desire to do stuff that would make for a more prosperous, and fairer, New Zealand than one is likely to hear from our current crop of political leaders in an entire election campaign.

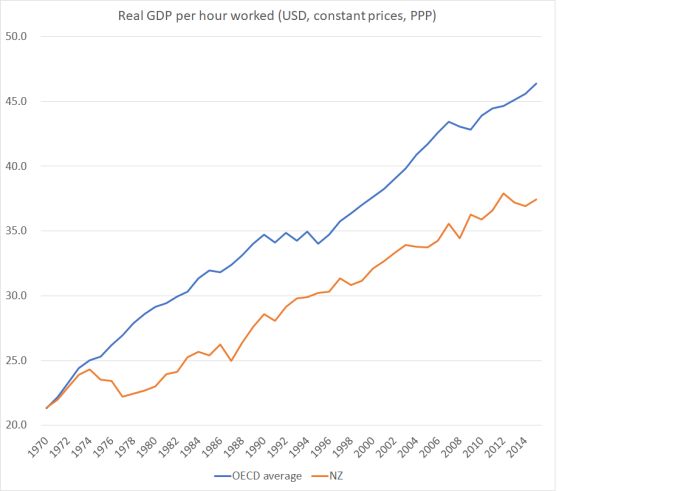

I very much liked the fact that they started their lecture with a chart of real GDP per hour worked (my favourite productivity indicator) for New Zealand and other OECD countries. Things are, very much, not okay economically was the intended message. Music to my ears.

Unfortunately, given that they made quite a bit of the graph, they got the wrong chart.

What they showed was something very like this.

Both speakers made something of it, telling of a large gap that opened up in the Muldoon years, but which then closed substantially again following the reforms of the 1980s and early 1990s, only to resume widening again in the last 15 years or so (when, as they noted, no politician has been willing to do any significant reforms).

But the chart looked a bit odd to me, and I wondered about all the new – mostly poorer – countries that had entered the OECD in the last couple of decades.

Sure enough, when I got home and dug out the data myself, it became clear that what they (or whoever prepared the chart for them – I think they mentioned the Reserve Bank) had done, was simply to average the real GDP per hour worked of whichever countries the OECD happened to have data for in any particular year. That is how I produced the chart above.

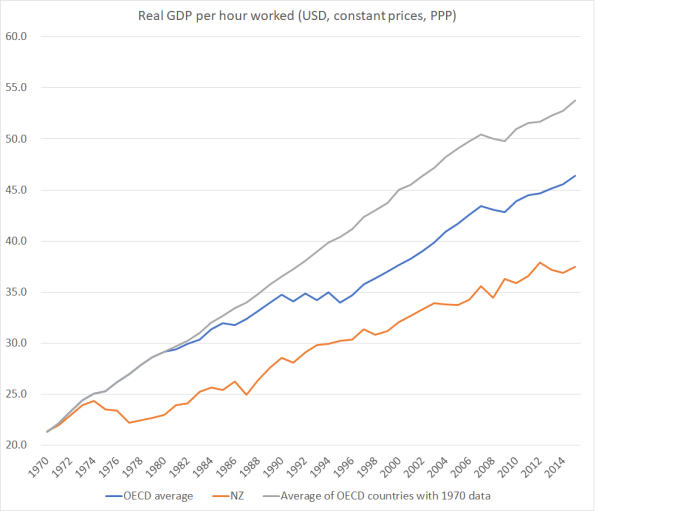

Unfortunately, in 1970 when the chart starts. the OECD had this data for only 23 countries. By 2015 it had data for 35. The odd rich country (Austria) was missing in 1970, but so were almost all the emerging markets and former communist eastern European countries now in the OECD (several weren’t even separate countries then). It is only since 1995 that the OECD has had data for all 35.

So here is another way of looking at the chart. The extra line is the average real GDP per hour worked for the 23 countries the OECD did have data for in 1970 – a fixed panel of countries throughout the whole period.

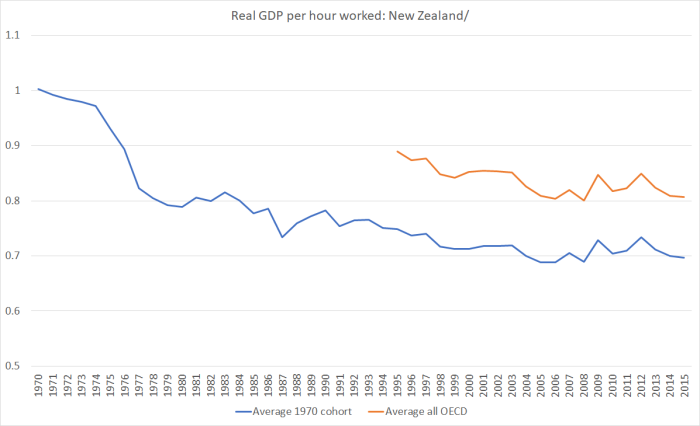

And here is how New Zealand productivity (on this measure) has performed relative to the OECD. I’ve shown both the measure relative to the average of the OECD countries with data for the whole period, and relative to the full sample of countries for the period since 1995 when data are available for all of them. Remember that most of the new-joiners are poorer than us, so the orange line is above the blue line.

There has been the odd good year here and there – and a few phases (including, actually, the Muldoon years, and the last decade) when we’ve gone sideways – but over the entire period since 1970 there has never been a phase when, on this measure, we’ve done consistently better than the group of other OECD countries. The pretty clear trend has been downwards.

I really wish it had been otherwise – not just because it is my country too, and I care about its fortunes, but because I supported a great deal of the reforms that were done (and which I still consider were mostly to the good). But even if the reformers expected, and hoped for, something better – some closing of the gaps – it just hasn’t happened.

I probably wouldn’t make much of it on this occasion, except that (a) Sir Roger is an eminent figure, and (b) the presentation yesterday, and the (no doubt unintentionally) misleading slide, was being presented to quite a large crowd of past and present econocrats.

However, the main focus of the Douglas/MacCulloch presentation was a proposal for a radical reshaping of the tax and welfare system. There is a nice accessible summary here (which includes a link to fuller versions). The gist of the proposal is as follows:

- much lower income tax rates,

- a lower company tax rate (and eliminated “corporate welfare”), and

- higher GST

But, “in exchange”, people have to contribute a set proportion of their income (and there is an employer contribution too) to dedicated private accounts for:

- health

- risk events (unemployment, disability etc)

- superannuation

There are lots of details, but on health everyone would have to buy an insurance policy against catastrophic events (anything more than $20000 per annum) and would have to meet other expenses either from their own health account, or if that was exhausted from direct government funding. Something similar applies to unemployment: your risk account is your first line of support, but if that is exhausted the government remains provider of last resort.

For retirement income, if I understand the scheme correctly, in many ways it isn’t much different than what we have now: a universal basic state pension, on top of which is private savings (including through Kiwisaver, although as they note Kiwisaver isn’t compulsory and their retirement accounts would be). The difference is that the age of eligibility would be gradually raised from the current 65 to 70.

It would represent a massive rejigging of the system. They argue that, in respect of health, it is largely the Singaporean model, and in Singapore health outcomes are very good and health expenditure (public and private) as a share of GDP is remarkably low. I don’t know enough about the Singaporean system to comment further, including whether it is likely to be replicable elsewhere.

There are all sorts of potential practical and philisophical problems. I wouldn’t rule out the possibility of some real benefits, for some people in time, or even more generally. But Douglas and MacCulloch argue that it is a politically feasible way to get necessary reform going again. And on that – fairly critical – count I’m sceptical.

In a fuller version of their paper they state

Most of the long-term reduction in government spending under the “Savings-not-Taxes” regime comes from the following sources. First, pension spending drops from $28.1b (under the existing system) to $17.4b (under the new regime) due mainly to the rise in the retirement age from 65 to 70 years old between 2015 and 2035. Second, there are the cuts in ‘corporate welfare’ and interest-free loans and grants to students from high-income, high-capital families.

In other words, huge changes to the entire tax and welfare system, to get the NZS age up from 65 to 70, to get rid of what they describe as (and I agree with them) as “corporate welfare” (film subsidies, Callaghan funding and so), and to eliminate interest-free student loans and related support to high income earners.

In the question time, I asked why they regarded the sweeping change as more politically feasible than simply focusing on those three items. I guess I sort of knew how Douglas would reply – it was a variant of a line he has used for many years, about doing lots of changes which can (a) distract people, but (b) provide an opportunity for everyone to benefit in some area. But I wasn’t really persuaded. They argue, for example, that people from high income families currently getting interest-free student loans would benefit from the lower tax rates in the Douglas-MacCulloch plan. Fair enough I suppose.

But the big money is in NZS cutbacks. It isn’t clear how the people who are most uneasy about raising the NZS age – the current middle-aged – are likely to benefit systematically very much from anything in the Douglas-MacCulloch package. Any gains/savings would be probabilistic at best (especially as health expenditures rise with age), and the potential personal losses (five extra years without NZS) certain and specific. I think change can and will be made – governments in the 1990s did raise the NZS age by five years, and got re-elected – but I don’t see how the huge “throw everything in the air” approach really helps. Grey Power, and Winston Peters, will be quite capable of seeing through to the bottom line.

Similarly, corporate welfare is a real scourge. But how does reforming the tax and welfare system on a large scale make it easier to, first, scrap those provisions, and then later resist the endless pressures that will come from various loquacious vested interests to put them back in place? I just don’t see it. It looks like an approach that, rather than making major savings more feasible, would simple multiply the number of enemies the reformers would make.

All that said, and sceptical as I am, it was good to see a serious plan outlined by people who really care. And credit goes to The Treasury for hosting the event.

(In passing I’d also add that one thing I really like about the package is that it would put sickness, disability and accidents all on the same footing).

In many respects, the saddest line of the day was one made almost in passing by Professor MacCulloch. He told us that he administers a fairly generously-funded visiting professorship at the University of Auckland, which aims to bring in distinguished or innovative, leading international thinkers to contribute to policy debate and development in New Zealand. But the last three people who had been invited had declined the invitation to come. There was, so far as they could tell, nothing bold or interesting on the table here, no real prospect of significant reform, or interest in it from our political leaders.

Things were very different, in that regard, 20 or 30 years ago. It is not as if, sadly, we have in the interim solved all our problems, and re-establishing a position as a world-leading economy, or a world-leader in dealing with the various social dysfunctions. We just drift, and allow our elites to tell themselves (and us) tales about how everything is really just fine.

Funny you should write this article, when, in your previous article a comment about Sir Roger prompted me to go have a look at his wikipedia entry.

An entry that caught my attention:-

“In his maiden speech in the Address-in-Reply debate on 7 April 1970 he devoted the greater part of his speech to the case against foreign investment in NZ’s domestic economy.”

The more I analyse the conceptual philosophical components of foreign investment the more I have difficulty accepting the touted end benefits

Given your skill at laying your hands on archival material are you able to provide a link to that paper at New Zealand Parliamentary Debates Vol 365 pp. 123–128 – I would like to study it

LikeLike

Hi Michael

I’d be VERY wary of the Singapore health model – actually all Singapore data – as it’s almost certainly doctored (no pun intended).

Having lived in Singapore 9 years and had the odd exposure to the system including two operations, I can tell you the system is amazing BUT it’s also incredibly expensive. Basically, from what I saw if it it was a two-tier system. Those who could go private had amazing doctors and facilities – I stayed in one room after an operation which was Wall to wall marble ! – BUT for ordinary people they get the ‘HDB’ version which is very spartan. I’m guessing a lot of their data is not accurately capturing the private side – which anyone who can afford uses. They also have major problems with over use of antibiotics. As Trump says “who knew healthcare could be so complicated”

I’m always very wary of Singapore stories

LikeLike

Thanks Peter. I share your general unease about Singapore stories, so good to have some specific reasons to doubt the health one.

LikeLike

Well these graphs suggest Rogernomics did not lead us to the free market paradise Roger promised. Indeed the graphs demonstrate it failed our economy. Not even a smidgen of sustained improvement in these measures. Indeed Rogernomics produced the horrid inequality and hopeless underclass we have today.

And yet here Roger and his neo-liberal followers are, still chanting “more market, more market.”

Interestingly these graphs suggest the old socialist and mixed economy pre -1974 model served us well.

While I wouldn’t advocate a return to the repressive governmental controls of that model I think it is reasonable to suggest the free market model is no better.

Perhaps some new thinking starting from the premise that the economy should produce the greatest good for the greatest number is in order.

.

LikeLike

What the graph you are referring to doesn’t tell you is that rogernomics had only begun to have a long-term effect when Black Monday 19 October 1987 happened, global stock markets crashed, New Zealand suffered worse than many of the other markets. While most of the western markets recovered within 2 years, the New Zealand never recovered, the economy stalled and rogernomics did not provide a panacea to the event

LikeLike

“.. greatest good for the greatest number..” is the utilitarian view of morality that as an atheist I have myself but it does run into some difficulties at the extremes – I remember reading that during the rubber boom in Brazil a hundred years ago you could buy very young Polish virgins and from the point of view of the Polish economy this export may have met this criteria. It is difficult to balance a large number of small positives against a small number of dreadful negatives. Similar dilemmas occur when deciding which drug treatments will be provided by Pharmac or how many dialysis machines to have and who will use them.

I agree with you that a good society needs more than just a healthy economy. But it would help.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I like the proposal a lot and think it would help with rebalancing, efficiency, national savings, cost disease and equity. Not sure about the politics though. Seems like something you would have to spend political capital to do.

LikeLike

I don’t have much respect for Roger Douglas’s policy prescription. The analysis seems to blame NZ’s economic woes on the public sector -with the idea that if only it was more like the private sector, then that would fix NZ.

Health the area I work in. NZ in comparison to overseas does wonders on the smell of an oily rag. There is plenty of evidence that our health outcomes are quite good given the proportion of GDP the country spends.

Health accounts (to make the public health sector more like the private sector) is a dumb idea. It does not acknowledge that market failure exists in privatising health -in particular in the area of asymmetric knowledge wrt health treatments/outcomes and huge economies of scale -that push the industry to having one provider -for expensive A&E services, intensive care, expensive scanning equipment, consultant specialities……

I have talked to a Dutch GP who said health accounts was used in the Netherlands and it caused chaos in the mental health field -for obvious reasons -the asymmetric knowledge problem is even more extreme in this part of healthcare.

In my opinion, NZ in the 1980s did a good job of removing the politically connected, self-entitled wealthy elite -subsidised farmers and import license businesses who were gaming the system for their benefit but to an overall cost to NZ.

But that has been replaced by another self-entitled, politically connected, wealthy elite -individuals and businesses who game the system to benefit from property gains (and increases in population). Again at an overall cost to NZ.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I find it extremely difficult to understand how you could connect NZ trillion dollars worth of residential property to gaming the system and therefore at an overall cost to NZ?? Looks like a huge gain for everyone that owns a home. Sure looks pretty widespread and not just a few property investors. Everyone including you, is free to sell their property to another buyer at a much lower price than market price to stop prices going up. David Chaston of interest.co.nz recently completed a study on house prices and came to the conclusion nothing is really unusual about house price increases. It has been a norm in the modern era of health, long life and prosperity. Smacks of a wealth envy by the don’t haves.

Population pressures are driven by tourists and the international student community which is a massive $15 to $20 billion export industry. Migrants are taken in because New Zealanders need certain skills to keep their industries running and recently for Earthquake disaster repairs and chefs and foreign language speakers for the service industry. With more and more New Zealanders not leaving and more returning from Australia, fewer migrants will make the threshold. Younger Migrants have always been taken in to fill up the tax coffers and as a replacement policy to keep older kiwis from falling and drooling saliva all over the carpets with no one to care for them.

LikeLiked by 1 person

His readers picked a number of holes in that analysis done by Chaston;

http://www.interest.co.nz/property/87961/adjusting-inflation-gains-house-prices-past-four-years-are-actually-nothing-special

This one being particularly useful;

“… here’s the Gummster’s take on this excellent series of numbers … our nominal house price ( $NZ ) in 2015 was 74 times what it was in 1963 …

But our nation’s GDP ( $US ) has only grown 26 times in that time period ( $US 6.639 B in 1963 : $US 173.8 B in 2015 ) …

… so in relation to our GDP , the growth of our economy , houses are nearly 3 times the price in 2015 than what they were in 1963 … And yet houses are an unproductive asset”

The cost to NZ is reflected in our poor productivity.

LikeLiked by 3 people

It is doubtful NZ ever had a modern era productive economy when you start to add in the livestock which at the top of our peak productivity was completely reliant on 70 million sheep. Now currently 10 million cows. Economists fail to correctly calculate productivity especially in a archaic economy reminiscent of the Roman Empire where sheep and cows dominate the worlds economy. It is about time we started to become more modern in our appreciation of the modern era productive economy.

LikeLike

View at Medium.com

LikeLike

Increasingly it is becoming apparent that economists measure of productivity is badly wrong.

https://hbr.org/2015/09/what-economists-get-wrong-about-measuring-productivity

LikeLike

The “gaming” is fairly simple to understand, rather staggering, and must have had a huge effect.

If I use the Reserve bank’s inflation calculator. http://www.rbnz.govt.nz/monetary-policy/inflation-calculator I can quickly see that since Q1 1985 (the first Douglas budget) “Housing” has risen 249% more than “Wages”.

That anyone can say “nothing is really unusual” about this beggars belief. It’s inequity and iniquity on a vast scale. People must have literally made out like bandits.

LikeLike

The summary link suggests there would be a $3.2b rise in Goods and Services Tax – did they mention what percentage GST would need to be raised to in order to achieve that?

I also don’t understand the connection between the reform proposal and its potential to lift productivity from the perspective of economic theory – given that a lifting of productivity seems to have been the opening gambit in proposing such a reform.

I agree with Brendon’s comments and am particularly sensitive to any big policy moves toward privatisation of healthcare (I’ve got too many friends/relatives in the States whose whole life decisions seem to revolve around stresses/matters associated with their medical insurance/insurers – and their premium costs in addition to co-pays are just beyond belief). It seems to me that competition is non-existent and extortion is rife in that system.

That said, I fully support major reform of both tax and welfare, but from an economics perspective at this stage I am more inclined toward Morgan and Guthrie’s ‘Big Kahuna’. But I’ll read Douglas and MacCulluch in full too – as I do think NZ needs another 1980s style major overhaul – and I believe the more options on the table from different philosophical foundations the better.

LikeLike

I think the Gst increase was from 15% to 17.5%

LikeLike

17.5% is about far enough before the black market kicks in. And now I have to decide whether my daughter’s boyfriend who mows lawns for a living is cutting my lawn as a business transaction or as a gift to a friend and I’m just giving him cash because I’m feeling generous.

I liked 10% GST it was easier to calculate in your head. GST tends to hit the poor harder than the rich unless we add it to all property and in-feasibly to purchases made abroad.

LikeLike

Thats a lot of lawns to mow because the threshold for GST registration is $60,000. Under $60,000 you can run a business without charging GST.

LikeLike

Yes, I suspect the 2010 income tax/GST ‘switch’ was particularly regressive in its nature. And now Joyce has had to attempt to offset that regressive effect with additional welfare measures. No the answer in the long term.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am surprised that they began a presentation on health and welfare reform by revisiting our poor economic performance since the 1970s. Michael, were they suggesting that health and welfare are holding us back?

LikeLike

I think the story line was a little bit about that, but also a bit about social failure, and a more general desire to criticise the policy malaise of the last couple of decades and setting the scene to make the case for restarting radical reform.

But they could easily have done the presentation on the specific paper with nothing on NZ’s past econ performance.

LikeLike

Being in my ‘family establishment’ years those Muldoon and Roger Douglas eras almost seem comedic in retrospect. For many, of course, it was more a tragedy than a comedy. While NZ needed the reforms, the results were anaemic at best. It is a true wonder to me that Douglas can even get an audience.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Michael

I think your most pertinent observation in the original note is that the fire seems to have gone out of the NZ political machine when it comes to making major adjustments.

Its interesting reading the comments above as I’m sure they give clear evidence as to why capable politicians are not too enthusiastic about being the next Roger Douglas (or Max Bradford or Ruth Richardson). In NZ its clearly bloody hard to make changes and avoid being reviled.

Does Bill English or Andrew Little relish being hated? It seems not. Who can blame them?

As Michael Cullen and Bill have shown, you can get (at least) 9 years behind the wheel as long as you don’t turn it too hard.

Compounding the “problem” of conservatism brought on by fear of the electorate (and public stoning) is the grim reality that few politicians have much real capability.

Under National we have had 4 Ministers of Commerce. The first turned up with a huge will to make change and the ability to push his reform platform through, the subsequent 2 delivered to their capabilities which meant delivered nothing. The jury is out on the incumbent.

Is there an answer to these two impediments (conservatism and incapability) to government imposing difficult changes? The “solution” you quote Douglas as proposing is laughable.

Tim

LikeLike

Under an MMP government it is rather difficult to get all your minority support parties to bow to the governments will. Even with the landslide election victory that got National Party 60 seats out of 121 but this only represented 49.6% of the votes which meant that it is still only a minority government relying on other parties to form and stay in government.

It is unlikely we will ever see strong leadership government in NZ whilst we have MMP.

LikeLiked by 1 person

National+ACT had an absolute majority of seats at the 2008 election. Had National been seriously interested in reform, I don’t think they’d have had a problem getting the votes. (Getting re-elected might have been a different matter.)

LikeLike

Not sure anyone of us really votes for ACT other than Epsom voters that vote strategically to keep National in government. It does mean that no one really wants the extreme right wing policies that ACT proposes. The middle ground is where most of the votes are which unfortunately for Labour seems not to understand and have therefore swung too far left. Most of us do realize social welfare is the price of peace and stability. Better to pay welfare than to pay for barb wire, guns and security guards.

My natural vote is towards the Labour party being an employee but I have no choice but to vote National because Labour party does not understand its employee voter base talking ridiculously about taxing property when it is employees that buy rental property. Employees = Labour. Talk about dumb and stupid.

I do think that National Party have given away too much to the Maori Party though in terms of dropping Helen Clarke’s Foreshore and Seabed Act, but I can see why Key has done it. Clearly he needed to balance the flakiness of Peter Dunne and the extremism of David Seymore. But kudos to the Maori minority that they are able to extract so much from a MMP tail wagging the dog type of government that we now have.

LikeLike

Theresa May in UK is finding out what MMP in NZ looks like. I cannot believe that she would give up 5 years of government and call a snap election to gamble that the Conservatives can garner 100 more seats under an MMP government. Sure looks like she is going to be Prime Minister of the UK for a very short time. Wonder if she breaks any record for the shortest term UK Prime Minister ever.

LikeLike

In the last 100 years, Bonar Law served for a shorter time.

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Bonar-Law

Fascinating viewing tho, and still early….

LikeLike

Interesting question Tim. I’m not sure I know the answer, but altho our economic performance (productivity) problem is clearly much more serious than those of other Anglo countries, I’m not sure there is any greater interest in reform in the other Anglo countries.

Maybe it is worth reflecting on what created a climate where radical change happened in the 30s or 80s. Something about large sudden adverse shocks on the one hand, and political leaders with a vision of something different. In the 80s case, perhaps that was Jones (as stalking horse) rather than Labour – the 84 Labour Party certainly didn’t campaign on radical change, but Jones shook free enough centre-right voters, with a message that something was v badly wrong, to make the Douglas agenda possible.

The problem now is that, housing aside, there is no general felt sense of a severe problem – the drift downwards in relative productivity is slow, the unemployment rate (while too high) hasn’t shot up massively, And housing is one where, for all the concern many will have for the next generation, there is the fear of what change might mean.

Does it need a crisis – even a pseudo one – and a leader with vision and selling ability to combine. I wonder how long we might have to wait.

LikeLike

The graph (either one) simply shows what we all now know – and that is that the regime Douglas encumbered us with was an outstanding failure !!!

The promises he made back then have never even remotely come true. Well I guess thats not fair. Trickle down and all that stuff hasnt come over the horizon yet. But his promise of lower wages certainly have come true.

All the emphasis on productivity is quite simply wrong. That only applies if a country is making low cost commodity products that throughout history get cheaper and so yes productivity does matter. BUT thats not any way for a country to get rich and the emphasis on productivity simply pushes various outfits into never ending cost cutting – and consequent income reduction.

There are plenty of examples around the world of better standards of living that come from intellectual property, exclusivity, a better resource, application of new technology, etc, etc

For example one of new zealands advantages is water – yes Water. Currently we export in the form of milk products and red meat. The answer – cut the crap and export water – and yes use developing technology to make GE meat (made from anything but meat – its actually been around a while) and manufactured milk (Its only chemicals after all).

LikeLike

Actually I think most of our milk is exported as milk powder. I used to work for Rockwell Automation and Fonterra has some of the largest milk drying machinery in the world spending around $40 million a year in US manufactured automation blowers and dryers. And that’s only the Rockwell equipment and of course there is also ABB, Siemens, Honeywell, and the Japanese.

LikeLike

I’m a little bemused that serious people still think microeconomic reform can possibly lead us into the promised land. Douglas’ reforms, as noted in this post and in comments, did not achieve nirvana, yet Douglas is still chewing on that bone.

I suggest that is because he has no real new ideas and, like many governments, just wants to double down on previous reforms that have failed and somehow expecting a different result – the latest example is in thinking ever increasing surveillance and repression of civil liberties in the West will somehow eliminate the scourge of terrorism. In reality, doubling down like that without addressing the root cause – Western military and political intervention in the Middle East – already dooms those policies to failure.

On productivity in the mature advanced economies, the broad principle is well established: it’s investment in technology that drives productivity.

But what drives investment? Most crudely, it is replacing labour with capital, generating higher returns for the owners of capital but, of course, lower returns for labour. This is the real world most advanced economies inhabited between WWII and 1980. And it worked, albeit undone by crass macroeconomic (mis)management (vulgar Keynesianism, as Jeffrey Sachs put it).

It’s well established that the reforms of the 1980s aimed to, and did, reduce the cost of labour in the hope that the owners of capital would use their gains to accelerate capital investment. Otherwise, other than class warfare, why do it? But, in fact, the opposite happened because in the face of lower real labour costs, companies have less inventive to invest.

Compounding the above, rapidly ageing societies simply have less need for technological advances (except in health, of course).

So, perhaps we have been eagerly ‘reforming’ the supertanker by pointing it in the wrong direction.

Maybe, to prise loose the hoarded wealth of the owners of capital, we need to increase the labour share of income by government fiat. Maybe then, If people really do respond to incentives, and surely the owners of capital are people, too, then we can solve the productivity puzzle.

On the other hand, maybe we should just accept that mature, advanced economies should be delighted with 1% real per capita GDP growth, forgetting about productivity, and the government’s job is to spread the wealth around to at least maintain the new economic paradigm.

LikeLike

I should clarify the 4th paragraph. In that era, displaced workers could readily find new jobs because economic activity was so vibrant that creative destruction really was the way the world worked.

LikeLike

I don’t think displaced workers readily find new jobs. Thats the fairy tale ending. In reality many would just end up doing whatever is available, cleaning toilets, sweeping roads and dying in poverty. Its just the new generation replaces the old aging ones, times passes very rapidly and people forget ugliness too easily and the perception is that displaced workers get retraining and redirected and all is well.

LikeLike

Yes, that labour share of income problem is a really interesting one. I know very little economic theory, but the problem for the world as I see it from my lay perspective, is that wealth distribution has got so out of kilter that the really significant stores of wealth are concentrated in so very, very, very few owners of capital. Therefore, any attempt to solve the crisis in the labour share of income by way of government fiat (i.e., I assume you mean mandated wage rises) could well harm a vast majority of the business/employer owners of capital and spark widespread inflationary effects in those economies where a government chooses to implement such measures.

Which is why I believe considerations with respect to UBIs have gained more attention of late. But of course, they too have to be funded and in a place like NZ, that funding will come from owners of capital who themselves are not uber wealthy by any measure (as per the Morgan/Guthrie proposal in the Big Kahuna).

And that leaves me with thinking that perhaps the only way to stave off the growing disappearance of the middle classes (if it is to be via a UBI mechanism) is to globally reform corporate tax treatment and wealth/capital storage/tax avoidance mechanisms.

One of the most odd of the neoliberal ideological tenets to my mind is the idea that the growth of philanthropy is a positive function/aspect of a ‘good’ capitalist society. We award knighthoods and other honours for it to individuals who have elaborate trusts and other financial mechanisms in place to avoid paying both corporate and income taxes. It seems so ridiculous.

As Elizabeth Warren pointed out in the States – all she asks of corporate entities and individuals is that they just pay their taxes – and that will do.

LikeLiked by 1 person