I’ve never had that much interest in climate change. Perhaps it comes from living in Wellington. If average local temperatures were a couple of degrees warmer here most people would be quite happy. And as successive earthquakes seem to have the South Island pushing under the North Island, raising the land levels around here – you can see the dry land that just wasn’t there before 1855 – it is a bit hard to get too bothered about rising local sea levels. Perhaps it is a deep moral failing, a failure of imagination, or just an aversion to substitute religions. Whatever the reason, I just haven’t had much interest.

But a story I saw yesterday reminded me of a post I’d been meaning to write for a few weeks. According to Newshub,

In documents released under the Official Information Act, a briefing to Judith Collins on her first day as Energy Minister says the cost to the economy of buying international carbon units to offset our own emissions will be $14.2 billion over 10 years.

In the documents, officials say “this represents a significant transfer of wealth overseas”, and also warn “an over-reliance on overseas purchasing at the expense of domestic reductions could also leave New Zealand exposed in the face of increasing global carbon prices beyond 2030”.

The cost amounts to $1.4 billion annually.

The Green Party says the bill will only get bigger if no action is taken by the Government to reverse climate pollution, and it continues to open new coal mines and irrigation schemes.

Roughly speaking, this suggests we’ll be giving roughly 0.5 per cent of GDP each year to people in other countries, just because of an (inevitably) somewhat arbitrary emissions target. Many useful economic reforms might struggle to generate a gain of 0.5 per cent of GDP. These are large amounts of money, inevitably raised at a still larger real economic cost. And this is on top of the economic costs of domestic abatement policies.

Of course, whatever New Zealand does in this area makes no difference to the global climate. We are simply too small. Most people recognise that we sign up to arbitrary targets through some (not unrelated) mix of wanting to be a good international citizen and (perhaps as importantly) being seen as a good international citizen. If we were regarded as not “doing our bit” there might be a risk of trade restrictions or other adverse repercussions a little way further down the track.

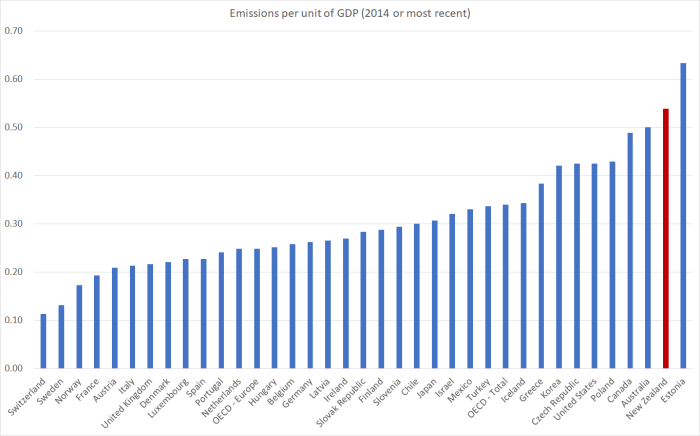

If one is an emissions and climate change zealot, the New Zealand data looks like it could give you grounds for zealotry. For example, here are total emissions (in CO2 equivalent terms) per unit of GDP (using PPP exchange rates), from the OECD databases. Why per unit of GDP? Well, generating GDP takes various inputs, and emissions of greenhouse gases are often one of them.

But emissions levels are, at least in part, about geography and industry structure. They aren’t just a matter of “wasteful” choices. Thus, steps to reduce emissions might also reduce the number of units of GDP. (In emissions per capita terms, we don’t rank as far to the right – being quite a lot poorer than (say) Australia, Canada and the United States).

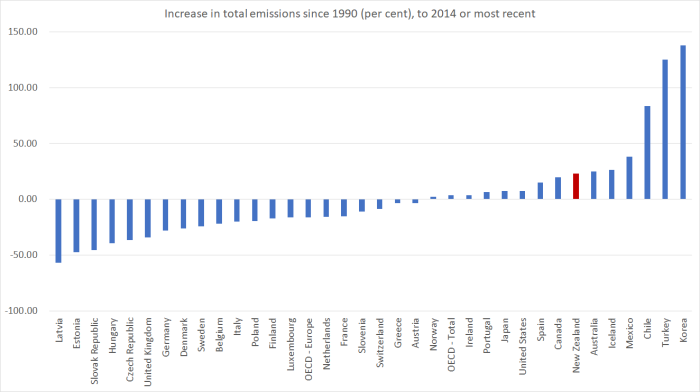

The self-imposed emissions reductions targets are, I gather, expressed in terms of total emissions. Again using OECD data, here is how the various countries have done on that score since 1990 (the typical reference date – and a somewhat convenient one for the former eastern bloc countries, which often had very inefficient heavy industries).

But one of the things that marks us out relative to most of the OECD (and certainly relative to those former eastern bloc countries on the left of the chart) is the rapid growth in population we’ve experienced since then. In fact, New Zealand’s population has increased by more than 40 per cent since 1990. By contrast, all the world’s high income countries’ population has increased by only around 15 per cent over the same period. And all else equal, more people tend to mean more emissions (although no doubt it isn’t a simple one-to-one relationship).

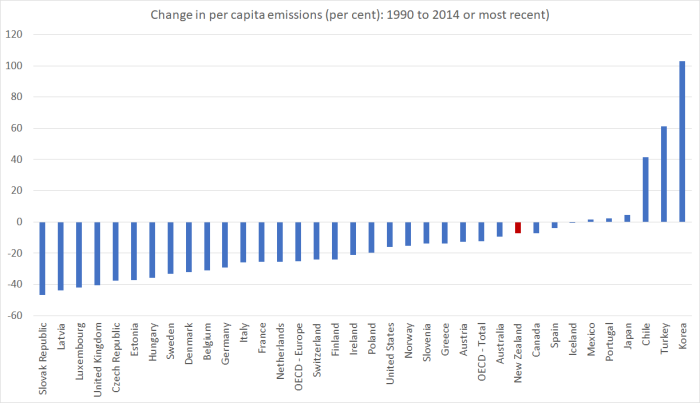

In per capita terms, our greenhouse gas emissions have actually fallen since 1990. Of course, so have those of most OECD countries. Here are the data.

Our average per capita emissions have been falling less rapidly than many other OECD countries, but not that much less rapidly than the OECD total. And all this in a country where I gather – from listening to the occasional Warwick McKibbin presentation – that the marginal cost of abatement is higher than almost anywhere in the world. Why? Well, all those animals for a start. And the fact that we already generate a huge proportion of our energy from renewable sources (all that hydro). And, of course, distance doesn’t help – aircraft engines use a lot of fuel, and neither a return to sailing ships nor the prospect of, say, solar-powered planes at present seem an adequate substitute.

So you have to wonder how our government proposes to meet its self-imposed targets, without doing so at great cost to the living standards of New Zealanders.

In fact, it seems the government is wondering just that. A few weeks ago,

The Minister for Climate Change Issues, Hon Paula Bennett, and the Minister of Finance, Hon Steven Joyce, today announced a new inquiry for the Productivity Commission into the opportunities and challenges of a transition to a lower net emissions economy for New Zealand.

The terms of reference are here. As they note

New Zealand has recently formalised its first Nationally Determined Contribution under the Paris Agreement to reduce its emissions by 30 percent below 2005 levels by 2030. The Paris Agreement envisages all countries taking progressively ambitious emissions reduction targets beyond 2030. Countries are invited to formulate and communicate long-term low emission development strategies before 2020. The Government has previously notified a target for a 50 per cent reduction in New Zealand greenhouse gas emissions from 1990 levels by 2050.

Which does look a little challenging (in 2014 total emissions were about 3 per cent lower than 2005 levels – 30 per cent looks a long way away). That isn’t too surprising. After all,

- the marginal cost of abatement is particularly high in New Zealand

- the rate of population growth in New Zealand has been rapid, and

- the rate of population growth is projected, on current policies, to continue to be quite rapid.

In fact, SNZ project another 25 per cent population growth by 2050 – quite a slowing from here, but still materially faster than the populations of most other advanced economies will be growing. And, recall, more people typically means, all else equal, more emissions. The 2050 target, in particular, requires quite staggering reductions in per capita emissions – actual emissions now are a quarter higher than in 1990 – if anything like these population increases actually occur.

The terms of reference for the Productivity Commission inquiry go on at length about all manner of things, including noting (but only in passing) that there may be “future demographic change”.

Recall that New Zealanders are actually doing their bit to lower total emissions. Our total fertility rate has been below replacement for forty years. And (net) New Zealanders have been leaving New Zealand each and every year since 1962/63. If New Zealanders’ personal choices had been left to determine the population – the natural way you might think – total emissions in New Zealand would almost certainly be far lower than they are now. Check out the low population growth countries’ experiences in the second chart above.

Instead, we’ve had the second largest (per capita) non-citizen immigration programme anywhere in the OECD (behind only Israel), a programme that (as it happens) got underway just about the time (1990) people benchmark these emissions reductions targets to.

As I’ve noted repeatedly, neither the government (or its predecessors), nor the officials, nor the business and think tank enthusiaists for large scale immigration, can offer any compelling evidence for the economic benefits to New Zealanders (income and productivity) from this modern large scale immigration. And when they do make the case for large scale immigration, they hardly ever mention things like emissions reductions targets (I’m pretty sure, for example, there was no reference to this issue in the New Zealand Initiative’s big immigration advocacy paper earlier in the year). Even if, to go further than I think the evidence warrants, one concluded that the large scale immigration had made no difference at all to productivity levels here (and remember that, for whatever reason, we have actually been falling slowly further behind other countries over this period despite all the immigration), once one takes account of the substantial abatement costs the country is likely to face if it takes the emissions reduction target seriously, the balance would quite readily turn negative. We would need to have managed quite a bit of spillover productivity growth from our not-overly-skilled immigration programme (and recall that no gains have actually been demonstrated) just to offset the economic costs, direct and indirect, of meeting emissions reduction targets which are made more onerous by the rapid increase in population numbers.

So I do hope that as the Productivity Commission starts to think about how to conduct their emissions inquiry, they will be thinking seriously about the role that changes in immigration policy could play in costlessly (or perhaps even with a net benefit) allowing New Zealand to meet the emissions reductions targets it has set for itself. On various assumptions about the economic costs or benefits of immigration, how would the marginal costs of abatement compare as between lowering the immigration (residence approvals) target, and other policy mechanisms that are more often advocated in this area? It would be interesting to see the modelling work on these issues. If the Productivity Commission doesn’t take seriously the reduced immigration option, it would be hard not to conclude that ideology was simply trumping analysis.

Of course, reduced population growth through lower immigration isn’t a solution for every country. On the one hand, people who don’t come here, stay somewhere else. And on the other, most advanced countries have much smaller immigration programmes than we do. But if it isn’t a solution for every country, it looks like a pretty sensible and serious option for New Zealand specifically. And the interests of New Zealanders should be the primary focus of our policymakers, and their advisers.

It is also brings to mind the old question as to why the Green Party in particular seems to remain so committed to large scale immigration, and the “big New Zealand” mentality, that has driven politicians here (of all stripes) for more than a century. Not only would a lower population be consistent with New Zealanders’ personal revealed preferences (birth rates and emigration) and actions, it would assist in meeting emissions targets. Perhaps to idealistic Greens that seems like “cheating” – it doesn’t reduce global emissions, although it may put the people in places where the costs of reducing global emissions is cheaper than it is here.

But even if so, then what about one of those other pressing Green concerns – water quality and the pressure on the environment from the increased intensity of agriculture? There is increasing recognition across the political spectrum that there is a major issue here, and it is an area where New Zealand actions and choices make all the difference. Cut back the immigration target and, over time, we would see lower real interest rates and a lower real exchange rate. Against that backdrop it becomes much easier to envisage governments being able to impose much stiffer, and more expensive, standards on farmers (the offset being the lower exchange rate). With a less rapidly-growing population, the (probable) reduced growth in agricultural output would be less of a concern (economically) and real progress could be induced on the environmental fronts (emissions and water pollution etc), without dramatically eroding the competitiveness of New Zealand’s largest tradables sector.

(Much the same sort of argument can be advanced in respect of congestion and pollution costs associated with growth in tourism: less rapid immigration would result in a lower real exchange rate, making it more feasible (economically and politically) to levy the sorts of charges that might effectively deal with pressures that the sheer number of tourists is imposing in some parts of the country – in a country where the natural environment is really what draws people.)

It is past time for a serious debate on just what economic gains (if any) New Zealanders as a whole are getting from continued large scale non-citizen immigration. The emissions reduction target might be seen by some as an arbitrary, even unnecessary, intervention, and is no doubt seen by others as a moral imperative, perhaps the very least we could do. I don’t have a dog in that fight. But the targets are a fact – a domestic political reality, and probably an international constraint we have to live with even if we didn’t really want to. Against that background, and given the high marginal cost of abating greenhouse gas emissions in New Zealand, and with little or no evidence of other systematic gains to New Zealanders from the unusually large scale immigration programme we run, we really should be taking more account of our immigration policy in thinking about how best (most cheaply) to reduce effectively greenhouse gas emissions, as well as the water pollution that increasingly worries many New Zealanders.

It is the abundance of methane gas emissions from the 10 million cows that the world is concerned about and the increasing water pollution from the unmanaged droppings of those same cows. The other concern is of course the 3.5 million tourists in their freedom campers doting the landscape and dumping refuse into rivers and clogging up roadways with their slow leisure drives that hog up the smaller regional roads.

LikeLike

Never had much interest in climate change and you are a christian??

You need to change that.

LikeLike

So many Christians think. I’m not so sure. Each person has capacity and attention span for only so many issues, and I can think of many issues on which there is a more clear-cut Christian perspective (not, to be clear, typically those covered in this blog), and which get more of my attention/focus/concern.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Perhaps but we have been given the responsibility for the dominion of the Earth. I would have thought it should be right up there.

LikeLike

Yes, fully accept that. As I say, it may well be a failure of imagination, or the contrarian in me that simply pushes back against the zealotry that often seems to surround the climate change debate. I’m also conscious though of the increases in crop yields and hence real wealth/consumption to date (not necessarily replicable in the future).

And altho the intro to the post was deliberately a bit flippant, I’m sure that living in Wgtn probably is an influence. If so, quite possibly an unfortunate one in that regard.

But there are many injunctions in Scripture, all of which we are called to take seriously.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Another great column. Population planning is central to combatting climate change yet it is deliberately ignored because it is considered too sensitive or simply too hard. New Zealand needs to get its act together.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree – another great column.

NZ’s climate change response is yet another example of the failure of government. Its the government’s job to pull together all the issues and provide a coherent strategy to deal with all of them.

LikeLike

And all to achieve a 0.048 degree of temperature rise by 2100.

LikeLike

So we have to pay $1B to overseas countries for what? The immigration means the people have come from another country to add to our emissions – so the reduction in their country of origin has to be counted. And we the food we produce is used by other countries – so the agri-emissions will occur somewhere, So we should be able to discount that as well.

If sea levels are rising would the $1B/yr buy a lot of stopbanks? Or better still send it to third world countries for clean water programmes? If its people you want to save then the bang for buck there is far higher.

But climate change politics is never about solutions or saving lives is it. Its about power for those who cannot achieve it on their own merits.

LikeLike

Thats called the Fart tax for methane gas emmissions from our 10 million cows.

LikeLike

“Perhaps it is a deep moral failing, a failure of imagination, or just an aversion to substitute religions…” I grew up in an end-of-the-world cult and I recognise a similar apocalyptic psychology around climate change —

nearly every storm or flood is seen as a sign of end times (climactically speaking) even when there is no proof the weather event is in any way significant meteorologically. Which is not to say climate change theories are not correct in their gloomy predictions, but it has become just as much a religious movement as a scientific one (proved by the fact that anyone who doubts it is cast as a “denier”, which is a modern word for “heretic”).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Can NZ charge non-NZ citizen immigrants their share of the $1billion climate change bill?

LikeLike

Every NZ resident tax paying person is already paying for it. The question is whether those 10 million cows should pay more of that $1 billion cost.

LikeLike

For every 100 new PLT arrivals we need to increase the cattle herd by 300 to pay for the imported component of the newcomers upcoming consumption

LikeLike

PLT includes International students that already contribute $4 to $5 billion to the local economy, also the 32,000 foreign workers paying tax to the construction and service industries. Frankly we could do without those cows. Dairy industry is just unsustainable and far too damaging. More people would be better for the economy. 1.5 million Aucklanders generate $75 billion in GDP so much more productive than 10 million cows that generate only $11 billion in export GDP.

LikeLike

Can NZ charge migrants their share ….

Good question … a question that is not contemplated in Government’s immigration policy settings for the past 3 decades – every time a new PLT arrival lands on our doorstep NZ’s production of emissions immediately increeases and the source country of origin of that migrant goes down by a corresponding amount

LikeLiked by 1 person

Each additional cow generates the waste equivalent of 20 people.

LikeLike

The following was first written in 2010 and updated in 2011 and 2012 when the price of a barrel of oil was up around $90

“for every new migrant arriving in NZ, the incremental cost is an immediate additional imported cost to the economy of USD $800 pa per person”

One reason why NZ needs to consider closing its doors to immigration. Over the past 10 days 2 comments have been posted (by some-one else) drawing to your attention that NZ consumes 160000 barrels of oil per day. That’s 13 barrels of oil per person per year for every one of 4.4 million ppl. Man, woman, and child. A cost of USD $800 per year per person. (NZD $1000). However that is (currently) offset by NZ production of 90000 barrels per day which is exported, leaving a net cost per person of USD $500 pa. The problem is those fields producing the local 90000 bpd will be exhausted within the next 10 years. Which means in 10 years time the imported costs to the existing population will increase from USD $500 pp to USD $800 pp in constant $ terms.

HOWEVER, for every new migrant arriving in NZ, the incremental cost is an immediate additional imported cost to the economy of USD $800 pa per person.

AT current July 2012 cost of USD $90 pb the annual additional (imported) cost is now USD $1170 or NZD $1450. Thats crude oil, not the processed refined cost.

iconoclast 21 Oct 2011

http://www.interest.co.nz/property/56293/further-improvements-nzs-balance-sheet-needed-theres-sustained-pick-national-property#comment-649825

LikeLike

A barrel of oil has fallen to $43 a barrel.so you need to update your numbers. But factor in electrification of cars as soon as Elon Musk can get his gigafactory up and running the consumption of oil drops even further.

LikeLike

Can you please advise how we will acquire all those Tesla’s without overseas funds and without having to increase the dairying herd and the upcoming exhaustion of all our oil and gas fields

LikeLike

NZ household net wealth is $1.2 trillion and that’s not anything to do with the Dairy industry. Plenty of spare capacity to buy Elon Musk’s teslas.

LikeLike

Well Mr bill doesn’t think anything needs to change with immigration settings and indeed the Govt. line is we need more workers to build more houses to fill with more immigrants who will buy and use more cards, planes and roads.

Virtuous circle stuff.

http://www.interest.co.nz/property/87849/no-reason-change-migration-settings-construction-english-says-defends-inability

LikeLike

Now you’ve set Grate Stuff off raving about the 10 million cows again but, seriously, why did we end up being responsible for agricultural emissions created to produce other peoples food? That’s not reasonable. Same with, for example, Chinese steel. The responsibility belongs to the end consumer IMHO.

Additionally, apart from climate change, there are multiple issues staring us in the face: mineral and biological resource depletion, species extinction, plastics pollution, sea, land and air degradation.

We have huge issues looming and all caused by extreme population overshoot, including the ongoing Middle East/North Africa disaster. Even countries such as the UK, apart from having massively degraded their natural environment are now incapable of providing for the food, energy and raw material needs of it’s current population. Worse, their environmental footprint extends all the way out to our green and pleasant land. Places like Bangladesh – what can you say? Maggots on a piece of rotten meat? something like that. We need a couple of spare planets perhaps but we can be an example to the world. The last thing this world, this country and our fellow species need is more people.

LikeLike

Change it to insect protein. Hugely more protein per sqm.

LikeLike

Problems are merely a holding position awaiting a scientific solution. Too many people, too many immigrants, too many cows, too many Erlich’s – too little belief in science to provide an answer. Unless of course one has a political agenda……..

LikeLike

I’m not sure what you have in mind but no doubt there are, at least theoretically, technological solutions to some of the issues Owen but have we the time and can we afford to implement them on such a scale. For places like Bangladesh or North Africa it’s already too late; they have already dangerously compromised their supporting environment. Seriously though, do you think it’s a good idea to pretty much carry on with what we’re doing if there is even a possibility of collapse through overpopulation and it’s consequences.

Compromising the myriad life support systems of our one and only planet, our earth, on a possible “scientific solution” would have to rank as one of the most absurd suggestions I have ever heard.

LikeLike

In response to David George. Show me a problem that was deemed “catastrophic” in the last two hundred years that wasn’t remedied by science. Medical problems are a good illustration.

Close to home we are well on the way to fixing the issues that caused the so called “dirty dairying”. Science and technology has been applied and answers delivered. The leaching of nitrogen is being tackled and answers are emerging. Rivers are improving except for the nitrogen issue.

I did not propose “doing nothing”. I am a strong believer in investing heavily in R and D as the most effective means of dealing with problems. Having travelled in East Germany before and after the wall I am astonished how a desolate and seemingly irreparable landscape, polluted waterways, foul air, etc has been turned around.

The river Thames is a well known illustration. As we become aware of problems and we demand answers they are found, not always quickly but eventually and we move on.

If immigration and too many people is a real problem and the community recognises it we will deal to the problem. It may be “absurd” to you but it sure works.

LikeLike

Well of course we should attempt to mitigate damage to the environment, that is what I said in the first place. Carrying on our current path carries such a huge risk it cannot be justified, nor can assuming an answer will appear simply because it has in the past. Some things are just not worth the risk and mans history of pollution, depletion, extinction and habitat destruction provides no comfort at all.

In many case we well know the answers but lack the will or the door has now closed to implement them, we have pushed ourselves so hard up against natural limits that in many cases there is no option but looming collapse. We have northern hemisphere boats fishing the Antarctic, mines tapping minerals of increasingly infinitesimal purity, drilling for oil in the most extreme conditions, oceans with more plastic than fish; none of that indicates a world with any more capacity for more consumers – we are beyond safe limits now.

So my point is, yes while we can overcome some localised problems, a sustainable future remains only a remote possibility with our present population never mind increasing it like we have – fifty year doubling time anyone?

Perhaps philosopher Nassim Taleb can help make the point. “We have only one planet. This fact radically constrains the kinds of risks that are appropriate to take at a large-scale. Even a risk with a very low probability becomes unacceptable when it affects all of us –– there is no reversing mistakes of that magnitude.”

https://fabiusmaximus.com/2016/07/06/nassim-nicholas-tabel-climate-change-risk-98101/

LikeLike

“Show me a problem that was deemed “catastrophic” in the last two hundred years that wasn’t remedied by science.”? What about the Irish Potato blight? Population of Ireland in the 1840s was 8 million and is now 4.5 million.

Looking this up on Wikipedia found a quote that may be relevant to various current issues: “between 1801 and 1845, there had been 114 commissions and 61 special committees enquiring into the state of Ireland, and that without exception their findings prophesied disaster; Ireland was on the verge of starvation, her population rapidly increasing, three-quarters of her labourers unemployed, housing conditions appalling and the standard of living unbelievably low.”

The trouble with history is it is too optimistic: only written by survivors. Is there a history of Tasmania written by first nation Tasmanians?

LikeLike

And this from August 2011

Consumption of Oil Imports. That is one of the most powerful reasons why New Zealand has to curb immigration. Alternatively every migrant arriving in the country should be required to put up a bond or deposit of $5000 pa for every year of the expected duration of their stay in the country. At the expiration of each year $5000 is taken out into the consolidated revenue for the oil and petrol they will consume. A migrant arriving at age 20 with a life expectancy of 50 years should put up a bond of $250,000. Otherwise New Zealand will have to work the treadmill faster and pull on the cows teat that much harder. If they leave the country they can have the un-consumed remainder of their account back.

iconoclast 31/08/2011

http://www.interest.co.nz/opinion/55136/wednesdays-top-10-nz-mint-bill-gross-whats-really-wrong-australian-free-trade#comment-640397

LikeLike

Your studies are totally outdated with todays electrification progress and oil price collapse.

LikeLike

I dealt with the idea of a fee for immigrants in this post

https://croakingcassandra.com/2017/03/22/new-zealand-initiative-on-immigration-part-10-recommendation-and-conclusion/ responding to the New Zealand Initiative having floated the idea.

In that post, I just took account of public infrastructure, but in principle one could add these sorts of additional external liabilities. (at one extreme, $1bn per annum is just over $200 if divided by 4.7m people including the new migrants, or something over $20000 if all the $1bn annual cost was assigned to the 45000 annual new migrants. Neither number would be a proper estimate of the marginal cost.

Personally, I have mixed views on a fee. If we are going to have large scale immigration some such arrangement makes a lot of sense (for non-refugee migrants). But if we cut the numbers back to, say, 10000 to 15000 per annum, quite a few of whom would be spouses of existing NZ citizens, I’m not sure I think it would be worthwhile, or that fair. For the remaining non-family places, we could be a lot more demanding in our skills tests, and give ourselves a much higher chance that NZers would benefit from the migrants, without the more crudely mercenary approach of a fee.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Recently, not so long ago, about 1 month, one young person standing on the parapet of Grafton Bridge brought the entire city to a grinding halt for half a day, then 2 weeks later, one single person driving north on the Southern Motorway had a heart attack under the Penrose overpass, which again, one single event, brought the entire city to a grinding halt for nearly half a day.

Which raises the question if we are absorbing nearly 1000 new arrivals into Auckland every week and adding 400 additional motor vehicles to Auckland roads what is the cumulutive impact on the heart of the city by adding just one more migrant and one more vehicle

LikeLike

Then we should have leveled Mt Eden, One Tree Hill and Mt Roskill and built 50/60/70 level tower buildings. We would not have the traffic congestion that Aucklanders are currently faced with in their daily commute.

LikeLike

The average dairy farm in NZ has the same greenhouse gas emissions as 700 cars. But when methane capturing through indoor farming has proposed, it doesn’t suit the green party types- in case the cows are offended. So it has never got much traction here.

Also cars are not as big a factor as you would imagine – I think all the cars in Auckland only produce about 3% of NZ greenhouse gases – but accept about 90% of the guilt. Buses produce more ghg emissions per person than cars – so changing to public transport will make the problem worse. Of course taxis and Uber are worse still.

But you never hear these ‘real’ figures. Only that Sweden did something so we should.

LikeLike

I don’t think you are measuring the same type of emission, Cows belch methane gas which is a 100 times more damaging to the Ozone than a cars carbon dioxide emission.

LikeLike

I think the figures take that into account. A cow does the damage of 1.5 cars – but the car would pump out a lot more volume of gas than the cow.

And you right – its belching so the ‘fart’ tax is not really accurate.

LikeLike

“Agriculture has long been a sticking point for efforts to reduce emissions in New Zealand.

In 2003, the government tried to levy farmers to pay for emissions research. Dubbed the “fart tax” (burps are actually more of a problem), it was met by protests organised by Federated Farmers. In what became an enduring image of the protest, National MP Shane Ardern – who also farms in Taranaki – drove a tractor up the steps of Parliament.”

http://www.nzagrc.org.nz/news,listing,133,our-problem-not-our-grandchildrens.html

An Industry dubbed standard so I guess we are stuck with the name Fart Tax.

LikeLike

“Perhaps it is a deep moral failing, a failure of imagination, or just an aversion to substitute religions”

Yes to the first two, the third is simply ad hoc justification of your aforementioned failings.

And “I’m alright, Jack” is just as destructive as “beggar thy neighbour” trade policies.

I suggest you read “Storms of My Grandchildren” by James E. Hansen. If you wish, I will happily post you my copy. And his website contains later papers, especially on projecting future possible consequences of our carbon emissions based on paleoclimatology – the study of millions of years of data: compare that to economics, covering a relatively shallow timespan.

It’s worthwhile noting that for us late-life fathers of primary school aged kids, the title “Storms of My Children” would be more apt. Just fifteen years ago, a common line was that adults then would not see any visible effects in our lifetimes. That thought has perished in the wake of non-stop climate disasters around the world that nearly all carry, increasingly, a climate change component in their causation. This should be personal, for you and all parents and grandparents (I’m both, but the chronological order got a bit muddled)

And just as you would/should be disturbed if your economics knowledge, gained through decades of learning and practice, were derided as a religion (and all religions do deserve derision, in my opinion), so too are the dedicated atmospheric physicists -like you, mainly public servants – who warned us about the effects of burning fossil fuels as far back as 1894 (Arrhenius). Of course, now climate change reaches across all the physical sciences, absorbing the energies of many of our very best scientists.

This post and the comments flooding in does nothing for your overall credibility, in my opinion.

I do trust I have not caused offence.

LikeLiked by 2 people

No offence. I do, however, have a contrarian streak resistant to all zealotry.

But, as I said, I don’t have strong views on the climate issues, and the post treats the emission reductions target as a given (whether people like the target, disapprove of any target, or think the target should be more demanding. Then the main question the govt and its advisers should be grappling with is how best to meet the target. I suggest that not using policy to drive up the population might well be one of the lowest cost, non-distorting options, in the specific circumstances NZ finds itself in.

Perhaps that conclusion is wrong, but it is an analytical issues amenable to careful analysis and (to some extent) modelling. Perhaps there are cheaper/easier ways to meet the target. If so, by all means do those. Emissions targets won’t be a major strand of my arguments about NZ immigration policy, but equally it looks as if it might be a factor that needs to be included in the policy analysis mix.

LikeLiked by 1 person

There are, of course, competing scientific theories about greenhouse gases and their effects, not least that the gases being trapped in the atmosphere are preventing another ice age. Yes, these are real scientists, albeit in a minority, arguing this point of view! Those advocating current theories about climate change (or the dominant paradigm as philosopher of science Thomas Kuhn might call them) are unquestionably religious in their zeal for promoting them and also ridiculing dissent. It fits entirely with Kuhn’s description of “normal science” and how scientists behave. Michael is absolutely right to draw attention to that aspect of the debate.

LikeLike

“I do, however, have a contrarian streak resistant to all zealotry.”

There you go again, and I must say that the lack of self awareness from a self-described – I almost wrote self-confessed – “Christian Conservative” is almost endearing.

But the accusation of zealotry can be made against anyone who has studied a topic in depth and found that we can improve our lot by changing we way we are doing things, and advocating for that change. In many ways, then, societies evolves via zealotry. Maybe its not such an insult, after all…

I can’t resist this, sorry, but Noam Chomsky on climate change and economic theories is relevant in this discussion. (It’s only 2.37mins and is quite funny, in a dark way).

I would add RBC to Chomsky’s citing of EMH as stupid economic theories. Studying both of those for exams was an exercise in self control.

I take Michael’s point that we have dug a hole for ourselves on emissions policy (thanks to another zealot, Tim Groser), but some immigrants will be leaving a higher per capita emissions economy, others the opposite, and if you take a global perspective, which is the metric that truly matters, it’s pretty much a wash. The margins aren’t really relevant here.

Another point against Michael’s proposal is that we just don’t know who we are turning away, and may miss out on future brilliance – Steve Jobs’ parents were migrants.

The proven, first best policy for lowering population growth is poverty reduction, so I would rather focus on actually getting big bangs for our bucks, and work our Gini at least back to 1970s levels. This includes education, especially on climate change consequences – my 8yo daughter surprises me with her level of knowledge and concern (but not worry) already – which will accelerate emissions reduction as today’s kids become tomorrow’s adults (while we watch from our pastures).

So just as Michael attaches one of his hobby horses to emissions reductions targets and their consequences, I can attach one of mine (progressive policies).

And I reckon mine is better 🙂

LikeLike

I take it from your introductory comments that you are suggesting that Christian conservatism is a form of “zealotry”? It isn’t a description I recognise. Conservatism, to the extent it is a stable body of thought, is innately sceptical of large change, and inclined to stress the value (often hard to pin down) in established institutions and traditions. The very opposite of zealotry. As for the Christian side, it is faith that emphasises fallibility, fallenness, and the need for grace. Yes, there can and should be a zeal for the things of the Kingdom, but often with a sense that only at the end of all things, God’s judgement will restore the world to rights. Human effort and ambition makes a difference, but only to a limited extent.

As for population, well yes, New Zealand would have a flat or falling population if it was just down to the choices (individual) of NZers. And in most advanced countries there would also be little population growth. Immigration policy – a large scale government intervention – changes that picture quite markedly.

As for emissions policy, well yes I think the margins are relevant here. We NZers might want to do our bit, but doing our bit tends to be more expensive than for those in most other countries, and it isn’t obvious why we should exacerbate the pressures thru rapid govt-led population growth. If NZers were having more children, I’d have no argument.

LikeLike

Michael, I really do thank you for your considered replies. They are polished and illuminating. However… 🙂

Para One: this got to my funny bone. I’ve studied conservatism (did very well with my essay) and I would reply that of course, conservative can be zealots. At the moment, virtually the whole US administration can be described as zealots, along with their best friends, the tyrannical Saudis. You can see zealots in every sphere, including some climate change activists, and including, as Chomsky pointed out in the video link, in economics. My proof of your zealotry: “God’s judgement will restore the world to rights.”

So what is a Zealot? Courtesy of Online Oxford: A person who is fanatical and uncompromising in pursuit of their religious, political, or other ideals.

Ok, ‘fanatical’ may be a bit harsh, I thought, but there’s this, a definition of ‘fanatic’, from the same source: a person with an extreme and uncritical enthusiasm or zeal, as in religion or politics.

Again, I mean no offence, but whereas new scientific findings can easily alter my thoughts on the urgency of emissions reductions, no such avenue is available to you because that sentence of yours I quoted is not based on science – in fact, it specifically rejects science that says it is nonsense. I suspect you are definitely uncompromising and uncritical as regards this very marginal view of the world.

Para two: would a flat or falling population really increase a country’s citizens welfare? I think the empirical evidence weighs against this view, and it would actually turn out to be a strong economic headwind. Have you looked at this in the literature? Basically, flat to rising is the minimum we want to maintain per capita income in an era of rapidly ageing population. Governments actually live in the nominal, not the real, to keep their voters happy.

Para three: we know immigration fluctuates wildly, and the same settings that allow a boom in incoming migrants can easily accompany the opposite (of course, we don’t stop people leaving). So I agree with the government about avoiding a knee-jerk reaction to a (probably) temporary phenomenon. And the xenophobic nature of much of the opposition to immigration does not help our overseas image for when the time comes when we may be desperate for people to come (to support us in our retirement villages). That said, we need to be wiling to spend more now to facilitate that influx.

Now, you say if NZers were having more babies, you’d have no argument. So as a thought experiment, assume that we are, in fact, having more babies (Australia seems determined to bring that to fruition by driving us out), then solve the (lack of) reductions problem for that case, and simply apply it to the present reality.

Finally, the economic consequences of a 14-16b hit over 10 years is not that significant. It can be easily covered by reversing the previous tax cuts for the higher income earners (given their lower MPC, not an economic biggie) or by providing a safe haven for private savings, wherever they originate from i.e. issue govt bonds. Better to do one of those – or both – and concentrate on genuinely reducing our emissions at least cost. In fact, we may find it results in a net economic benefit, anyway. The unexpected does happen.

Cheers.

LikeLike

Luc

There is a lot there. Just quickly

1. I don’t recognise the current US administration as conservative, and certainly not as Christian conservative. If Pence ends up becoming President – a longer-term outcome I would welcome – I might have to reconsider.

2.I don’t understand why you think I couldn’t change my mind on climate science? At present, I don’t have much a view – as i said, I’ve never had much interest – and my interest is mostly in the economics and politics of how we achieve the arbitrary reduction target we have adopted.

3 Yes, I am quite comfortable that a flat or falling population would work out just fine. It has, for example, in various eastern European countries, and is in Japan. There is nothing in any literature I’m aware of that envisages major problems – and as I recall the first scholarly piece on the subject i read dates back as far as the late 1930s (when people were last worrying about the possibility of declining populations).

LikeLike

Michael,

My comment on whether you would change your mind refers only to your “God’s judgement…” sentence.

LikeLike

So much comment I’ve had to skim it or else I’ll not have dinner ready when the family returns. Meanwhile enjoy reading someone who likes the idea of increasing population: https://www.greaterauckland.org.nz/2017/05/23/new-zealand-plan-10-million-new-zealanders/

LikeLike

Thanks for the link. Peter Nunns’ story is in some ways a pleasing one……except for the small consideration of what all these people might do (earning first world incomes) here. Actively putting more people in this remote space with few strong economic opportunities beyond the fixed quantity of natural resources looks to have been a bad choice for the last 70 years. Things could change in future, but there isn’t much sign of that surge in productivity – signalling great opportunities for more people – yet.

LikeLiked by 2 people

$1.4 billion annually – does that equate to a separate tax bill of $1,000 per household? If it arrived in its own envelop maybe policy would change.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The average household has just under 3 people.

LikeLike

Please refund the overcharged amount to myself.

This is a rort attached to a ponzi scheme. Worse than our problem with Offshore Trusts for at least they are playing with their own money.

1.4 billion will buy a couple of hips, some decent mental health care for those with mental health issues that cannot help themselves.

Instead we pee it up against some wankers 300 million dollar business jet.

Sooner Trump cancels there’s the better and we can do the same.

We wonder why we are broke as a country. Stupid is as stupid does.

Remember the Danish story about the emperor with no clothes. Well this is the 21st century version.

Many years ago there was an Emperor so exceedingly fond of new clothes that he spent all his money on being well dressed. He cared nothing about reviewing his soldiers, going to the theatre, or going for a ride in his carriage, except to show off his new clothes. He had a coat for every hour of the day, and instead of saying, as one might, about any other ruler, “The King’s in council,” here they always said. “The Emperor’s in his dressing room.”

In the great city where he lived, life was always gay. Every day many strangers came to town, and among them one day came two swindlers. They let it be known they were weavers, and they said they could weave the most magnificent fabrics imaginable. Not only were their colors and patterns uncommonly fine, but clothes made of this cloth had a wonderful way of becoming invisible to anyone who was unfit for his office, or who was unusually stupid.

“Those would be just the clothes for me,” thought the Emperor. “If I wore them I would be able to discover which men in my empire are unfit for their posts. And I could tell the wise men from the fools. Yes, I certainly must get some of the stuff woven for me right away.” He paid the two swindlers a large sum of money to start work at once.

They set up two looms and pretended to weave, though there was nothing on the looms. All the finest silk and the purest old thread which they demanded went into their traveling bags, while they worked the empty looms far into the night.

“I’d like to know how those weavers are getting on with the cloth,” the Emperor thought, but he felt slightly uncomfortable when he remembered that those who were unfit for their position would not be able to see the fabric. It couldn’t have been that he doubted himself, yet he thought he’d rather send someone else to see how things were going. The whole town knew about the cloth’s peculiar power, and all were impatient to find out how stupid their neighbors were.

“I’ll send my honest old minister to the weavers,” the Emperor decided. “He’ll be the best one to tell me how the material looks, for he’s a sensible man and no one does his duty better.”

So the honest old minister went to the room where the two swindlers sat working away at their empty looms.

“Heaven help me,” he thought as his eyes flew wide open, “I can’t see anything at all”. But he did not say so.

Both the swindlers begged him to be so kind as to come near to approve the excellent pattern, the beautiful colors. They pointed to the empty looms, and the poor old minister stared as hard as he dared. He couldn’t see anything, because there was nothing to see. “Heaven have mercy,” he thought. “Can it be that I’m a fool? I’d have never guessed it, and not a soul must know. Am I unfit to be the minister? It would never do to let on that I can’t see the cloth.”

“Don’t hesitate to tell us what you think of it,” said one of the weavers.

“Oh, it’s beautiful -it’s enchanting.” The old minister peered through his spectacles. “Such a pattern, what colors!” I’ll be sure to tell the Emperor how delighted I am with it.”

“We’re pleased to hear that,” the swindlers said. They proceeded to name all the colors and to explain the intricate pattern. The old minister paid the closest attention, so that he could tell it all to the Emperor. And so he did.

The swindlers at once asked for more money, more silk and gold thread, to get on with the weaving. But it all went into their pockets. Not a thread went into the looms, though they worked at their weaving as hard as ever.

The Emperor presently sent another trustworthy official to see how the work progressed and how soon it would be ready. The same thing happened to him that had happened to the minister. He looked and he looked, but as there was nothing to see in the looms he couldn’t see anything.

“Isn’t it a beautiful piece of goods?” the swindlers asked him, as they displayed and described their imaginary pattern.

“I know I’m not stupid,” the man thought, “so it must be that I’m unworthy of my good office. That’s strange. I mustn’t let anyone find it out, though.” So he praised the material he did not see. He declared he was delighted with the beautiful colors and the exquisite pattern. To the Emperor he said, “It held me spellbound.”

All the town was talking of this splendid cloth, and the Emperor wanted to see it for himself while it was still in the looms. Attended by a band of chosen men, among whom were his two old trusted officials-the ones who had been to the weavers-he set out to see the two swindlers. He found them weaving with might and main, but without a thread in their looms.

“Magnificent,” said the two officials already duped. “Just look, Your Majesty, what colors! What a design!” They pointed to the empty looms, each supposing that the others could see the stuff.

“What’s this?” thought the Emperor. “I can’t see anything. This is terrible!

Am I a fool? Am I unfit to be the Emperor? What a thing to happen to me of all people! – Oh! It’s very pretty,” he said. “It has my highest approval.” And he nodded approbation at the empty loom. Nothing could make him say that he couldn’t see anything.

His whole retinue stared and stared. One saw no more than another, but they all joined the Emperor in exclaiming, “Oh! It’s very pretty,” and they advised him to wear clothes made of this wonderful cloth especially for the great procession he was soon to lead. “Magnificent! Excellent! Unsurpassed!” were bandied from mouth to mouth, and everyone did his best to seem well pleased. The Emperor gave each of the swindlers a cross to wear in his buttonhole, and the title of “Sir Weaver.”

Before the procession the swindlers sat up all night and burned more than six candles, to show how busy they were finishing the Emperor’s new clothes. They pretended to take the cloth off the loom. They made cuts in the air with huge scissors. And at last they said, “Now the Emperor’s new clothes are ready for him.”

Then the Emperor himself came with his noblest noblemen, and the swindlers each raised an arm as if they were holding something. They said, “These are the trousers, here’s the coat, and this is the mantle,” naming each garment. “All of them are as light as a spider web. One would almost think he had nothing on, but that’s what makes them so fine.”

“Exactly,” all the noblemen agreed, though they could see nothing, for there was nothing to see.

“If Your Imperial Majesty will condescend to take your clothes off,” said the swindlers, “we will help you on with your new ones here in front of the long mirror.”

The Emperor undressed, and the swindlers pretended to put his new clothes on him, one garment after another. They took him around the waist and seemed to be fastening something – that was his train-as the Emperor turned round and round before the looking glass.

“How well Your Majesty’s new clothes look. Aren’t they becoming!” He heard on all sides, “That pattern, so perfect! Those colors, so suitable! It is a magnificent outfit.”

Then the minister of public processions announced: “Your Majesty’s canopy is waiting outside.”

“Well, I’m supposed to be ready,” the Emperor said, and turned again for one last look in the mirror. “It is a remarkable fit, isn’t it?” He seemed to regard his costume with the greatest interest.

The noblemen who were to carry his train stooped low and reached for the floor as if they were picking up his mantle. Then they pretended to lift and hold it high. They didn’t dare admit they had nothing to hold.

So off went the Emperor in procession under his splendid canopy. Everyone in the streets and the windows said, “Oh, how fine are the Emperor’s new clothes! Don’t they fit him to perfection? And see his long train!” Nobody would confess that he couldn’t see anything, for that would prove him either unfit for his position, or a fool. No costume the Emperor had worn before was ever such a complete success.

“But he hasn’t got anything on,” a little child said.

“Did you ever hear such innocent prattle?” said its father. And one person whispered to another what the child had said, “He hasn’t anything on. A child says he hasn’t anything on.”

“But he hasn’t got anything on!” the whole town cried out at last.

The Emperor shivered, for he suspected they were right. But he thought, “This procession has got to go on.” So he walked more proudly than ever, as his noblemen held high the train that wasn’t there at all.

Hans Christian Anderson.

Doubt it is ever taught to children these days but lot of wisdom in the story.

Apologies for taking so much space.

LikeLike

No indeed, my 8 year daughter came home from school very excited talking about stories on how Moanna opens a coconut which got me totally confused about what was the underlying message and then broke out into a Maori song and dance, a totally hopeless second language that is not used other than by a few thousand people in NZ and no where else around the world. We sure are setting up our young New Zealanders to fail.

LikeLike

Michael, I accept your point about population (why not take the low hanging fruit) but I would not necessarily accept Warwick McKibbin’s assumptions about cost of abatement. Based on a comparison with some projects in Tasmania, I think utility scale solar in Marlborough could reach around 8c/kWh in the near future (including the cost of debt and equity). This would work quite well in combination with S.I. hydro. And electric cars will achieve cost parity with combustion vehicles sooner than most people think, for example https://cleantechnica.com/2017/05/20/ubs-chevy-bolt-drivetrain-4600-cheaper-thought-tesla-model-3-likely-profitable/. Finally, although NZ climate is not ideal for rooftop solar, the equipment is now so cheap (around 7c/kWh levelised cost in Eastern Australia, so perhaps it could get to 10-12c in Auckland) it will make sense for households to have small systems to self-generate during the day.

LikeLike

Thanks Blair. I guess Warwick’s estimate were done well before solar became economic. Having said that, as i think you allude to, one difference between NZ and Aus is that our residential power use is heavily to warm things, and yours is more to cool them. That aligns supply and likely demand better in Australia than it does in NZ.

We still face the twin issues of air travel (altho I’m not clear whether those emissions are in the target variable) and animal emissions, the latter of which are a disproportionate share of NZ emissions by OECD stds.

LikeLike

I read that article the other day and it was this that caught my eye:

“…while the government will wear the cost of buying credits for industries exempt from the Emissions Trading Scheme such as agriculture.”

So (whilst ag remains exempt) taxpayers, not farmers, will bear the cost of our methane gas emissions.

I’d rather my taxpayer contribution to this was used to pay landowners to reduce their emissions, as opposed to some (likely) offshore entity to purchase their credits.

In other words a taxpayer subsidy to buy animals off the land, but with a proviso that the subsidy can only be used to pay down debt – and any landowner taking on the subsidy to reduce herd numbers would also need to accept a covenant on the land title setting a maximum/sustainable animal weight limit with respect to future agricultural use – such as that used for land place in QEII Trusts;

http://www.openspace.org.nz/Site/About_covenanting/Buying_covenanted_land.aspx

Seems silly to spend the money to pay to continue to pollute. Why not spend the money to REDUCE our poilution? Isn’t that more a win-win solution to the problem of the CC/emissions reduction commitment?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sounds plausible to me Katharine. But I think it is partly where the population pressures come in – the felt desperate need to keep driving up export volumes to, in some sense, keep pace with the consumption needs of a rapidly growing population.

LikeLike

Absolutely, that’s definitely why the government keeps promoting intensification/increased production – given so many economic metrics are focused on GDP per capita.

This National government executive branch in a particular just simply doesn’t seem to have the intellectual firepower to think laterally and strategically (we’ve got no really new ideas aside from a national bike track) – that, or ideology simply gets in the way of their intellect and they are using Ministerial directions such that the departments come up with all the wrong outputs/conclusions.

Point is, I’m sure there are innovative, highly educated folks in the public service but they don’t seem to be making an appearance on the radar. Too much Ministerial oversight/influence I suspect is squashing innovation. The bright ones among the central government departmental ranks are either keeping their head down for fear of retribution if they don’t share in the executive’s ideological position or they are seeking employment elsewhere.

LikeLiked by 1 person