After the last OCR review I noted that if I was going to go on agreeing with the Governor, there might not be much point in writing about the OCR decisions. I agree with him again today.

Writing earlier in the week about what the Bank should do I concluded

So where does it all leave me? Mostly content that an OCR around 1.75 per cent now is broadly consistent with core inflation not falling further, and perhaps continuing to settle back where it should be – around 2 per cent. Of course, there is a huge range of imponderables, domestic and foreign, so no one should be very confident of anything much beyond that.

And I was pleased to see how much emphasis the Governor placed today on the inevitable uncertainties around the (any) forecasts and projections. Trying to project where the OCR might appropriately be a year or two from now is mostly a mug’s game. Getting the current decision roughly right is towards the limit of what the Bank can actually usefully do. I think they have today, although only time will tell.

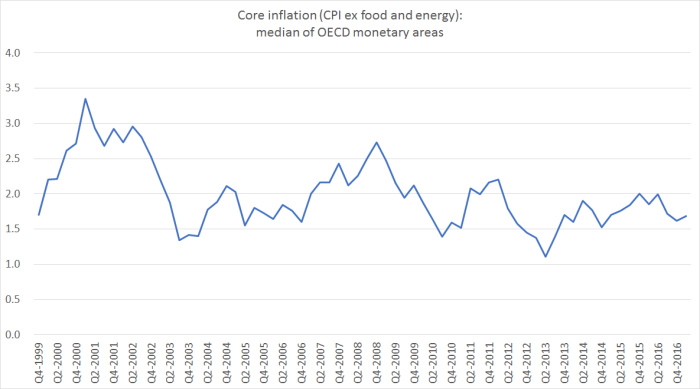

I also liked the continuing emphasis on how low core inflation is globally. This is my chart making that point, taking the median of the core inflation rates of the places in the OECD with their own monetary policy (so that the euro-area counts as one observation, and individual euro-area countries don’t count at all).

But there were some puzzles and some unsatisfactory aspects in both the statement itself and in the press conference the Governor and his chief economist just hosted.

First, it is quite remarkable that there is no mention at all in the document of the forthcoming hiatus. After 25 September, we’ll only have an acting Governor for six months (itself a questionably lawful appointment), and we won’t have a permanent Governor until next March. The Policy Targets Agreement expires with the Governor, and there won’t be a formal Policy Targets Agreement in place during the interregnum. The Reserve Bank Act requires that the Monetary Policy Statement address how the Bank will conduct monetary policy over the following five years. Given that we also have an election approaching in which most of the opposition parties are promising some changes to monetary policy, there is more than usual uncertainty about the path ahead – the people and the law/PTA to which they will be working. It isn’t the Bank’s place to take partisan stances, but it would be only reasonable – in a genuinely transparent organisation, complying with the law – to touch on these issues, if only briefly. At a trivial level, the PTA has been reproduced in the MPS for decades, reflecting the central role PTAs have in New Zealand short-term macroeconomic management. What will be done in the November and February MPSs?

Rather more importantly, although I agree with the Governor’s current stance, I’m not sure I’d be taking the same view as him about the outlook for monetary policy if I shared his economic forecasts.

Here is my puzzle. This is the Reserve Bank’s chart of their estimate of the output gap.

They now reckon it has been pretty flat around zero for the last two to three years. I’d be surprised if there has been quite so little excess capacity – and in fairness, they do explicitly highlight the quite wide range of estimates they have – but it is their current central view. But then look what happens starting now. They expect quite a material positive output gap to emerge. And they think that will translate into quite a lift in wage inflation.

Now, it is quite true that they need to see a lift in wage inflation if core inflation, across the economy, is to settle near 2 per cent, the target the Governor has committed to. But if I really believed that things in the wage-setting markets were likely to turn around that much that quickly, I’m not sure I’d be running with such an “aggressively neutral” (ANZ’s words) stance right now. Perhaps it doesn’t really matter to the Governor – the sole decisionmaker – because he won’t be there?

I’m a bit puzzled as to why they expect such a material increase in capacity, and wage, pressures. They expect to see real GDP growth accelerate a bit. Over the 18 months to the middle of next year, they expect quarterly growth to average 0.9 per cent. By contrast, in the last couple of years, on their preferred production measure, real GDP has grown by only 0.6 per cent a quarter on average.

It isn’t that clear why they expect such an acceleration (which we’ve seen forecast before). Perhaps it is partly the lagged effect of last year’s fall in the OCR? But then, as they note, bank lending standards appear to have tightening, and funding margins risen, which will offset some of the effects of the OCR cut. Dairy prices have certainly increased, which will provide some support to spending. The exchange rate has come down a bit recently (more so this morning) but the level the Bank assumes – a TWI above 75 for the next year or so – isn’t much below the average for the last couple of years.

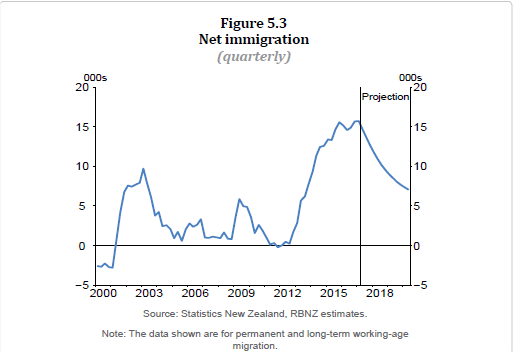

And then there is immigration. Here are the Bank’s projections.

They expect the net immigration numbers to start falling over very sharply, starting now. As the Governor noted, they (and other people) always get their immigration forecasts wrong. But any significant reduction in immigration – and this is a halving in the next couple of years – is a material reduction in both demand and supply for the whole economy. It is more than a little surprising that the Bank believes we will see both an acceleration in total real GDP growth and a sharp slowdown in net immigration.

The Bank appears to still believe the story that, at least this time round, high net immigration has eased overall capacity pressures. If they are sticking to that story – and they appeared to in the press conference – then perhaps that is why they think we should be expecting a sharp pick-up in wage inflation starting now. It doesn’t ring true to me – and it has never been how New Zealand immigration cycles have worked in the past – but if that is part of their story, something they genuinely believe, then – as I already noted – I’m a bit surprised by the “aggressively neutral” policy stance. On my own reading of course, any material slowdown in net immigration (unless it is accompanied by a big Australian economic rebound) will weaken near-term demand more than supply, as it has typically done in the past.

Two other points that came up in the press conference seemed worth commenting on.

Bernard Hickey asked the Governor what the Bank’s definition of full employment was. The Governor was quite open, if a little tentative, in suggesting something around 4.5 per cent. That is lower than the actual unemployment rate has been since the first quarter of 2009 – eight years ago. But, as Hickey noted, it is still above the Treasury’s published estimate of near 4 per cent. The actual unemployment rate now still stands at 4.9 per cent.

The Bank’s chief economist and Assistant Governor, John McDermott, then picked up the question. The gist of his response was that it was a silly question. At some length he tried to explain how the Bank relies on the output gap for its assessment of overall capacity pressures in the economy. He went to argue that labour market variables were so slow to respond that if one waited to evidence from them before moving it would almost certainly be “too late”. Doubling down, he argued that in a New Zealand context it was “almost impossible” to estimate any sort of NAIRU, and that any attempt to do so was just ‘guessing”.

In a way, I wasn’t surprised by these arguments. He used to run the same lines to me when I worked for him. But familiarity doesn’t make the arguments any more convincing. For a start, everyone recognises that inflation targeting is supposed to work by focusing on the forecast outlook, perhaps 12-24 months ahead. Monetary policy works with a lag. In principle, waiting to see actual outcomes – on whatever measures – will typically mean acting too late.

But, on the one hand, this is the very same central bank which set a new world record this cycle, by twice beginning to increase interest rates (in 2010 and 2014) only to have to quickly reverse themselves. It is quite a while since they were too late to tighten (and McDermott was the Bank’s chief economist in both instances).

And what of the output gap the Bank wants us to put our faith in? Here was one of the leading international experts (and a former practitioner) on inflation targeting, Prof Lars Svensson writing on measures of excess capacity (LSRU is the long-term sustainable rate of unemployment, the bit not influenced by monetary policy)

What does economic analysis say about the output gap as a measure of resource utilization? Estimates of potential output actually have severe problems. Estimates of potential output requires estimates or assumptions not only of the potential labor force but also of potential worked hours, potential total factor productivity, and the potential capital stock. Furthermore, potential output is not stationary but grows over time, whereas the LSRU is stationary and changes slowly. Output data is measured less frequently, is subject to substantial revisions, and has larger measurement errors compared to employment and unemployment data. This makes estimates of potential output not only very uncertain and unreliable but more or less impossible to verify and also possible to manipulate for various purposes, for instance, to give better target achievement and rationalizing a particular policy choice. This problem is clearly larger for potential output than for the LSRU.

He summed it up recently even more succinctly

My experience of practical policymaking made me very suspicious of potential output, essentially an unverifiable black box, and consequently of output gaps. Instead, it made me emphasize the (minimum) long-run sustainable unemployment rate and consequently the unemployment gap.

And it is not even as if McDermott’s point about lagging labour market data has much obvious validity relative to measures of the output gap. I had a look at the peak of the last (pre 2008) boom.

The unemployment rate troughed in the September and December quarters of 2007.

The output gap – as estimated today – peaked in the September quarter of 2007.

But that caveat (“as estimated today”) matters hugely. At the time, there was huge uncertainty about, and significant revisions to, estimates of the level of the output gap. In the December 2007 MPS, for example, there isn’t a chart of the quarterly estimated output gap. But the estimate for the average output gap for the year to March 2008 was 0.6 per cent. At the time, they (we) thought the output gap had peaked in 2005. The Bank’s current estimate is that the output gap in late 2007 was around 2.5 per cent. Those aren’t small differences. And they are pretty inevitable. By contrast, there has never been any doubt that the labour market was at its tightest in late 2007.

No one is going to disagree that it is hard to estimate a NAIRU – or Svensson’s LSRU – with hugely great confidence. But much the same – typically only more so – can be said of almost any of the concepts the Bank uses in its modelling, forecasting and policy assessments (eg neutral interest rates, potential output, and equilibrium exchange rate). And, relative to output gap measures, the unemployment rate is a directly observable measure of excess capacity, easily comprehended and prone to few revisions. And unemployment is something that citizens care directly about.

In McDermott’s shoes, I’d have said something like “we really don’t know, but we are pretty confident it is lower than the current 4.9 per cent unemployment rate. Treasury’s estimate of around 4 per cent might not be far from the mark, but we won’t really know until we get nearer. The fact that the unemployment rate is, with quite a high degree of confidence, above the NAIRU is consistent with wage and price inflation having been pretty subdued for a long time, and is consistent with the Bank’s stance, of keeping interest rates below our estimates of neutral for the time being”. It wouldn’t have been hard to have run that line.

Perhaps people (eg FEC) might like to ask the Bank why it appears to put so much less weight on direct measures of unemployment than, say, their peers in the United States (or most other central banks) appear to. None takes a mechanical approach, none assumes the NAIRU never changes, none assumes they know it with certainty. But they seem to think it matters – and might matter to citizens and politicians to whom they are responsible – in a way that simply eludes the Reserve Bank. It is partly why I’ve come to the conclusion that some form of what the Labour Party is promising – a more explicit statutory focus on unemployment in the documents governing the Reserve Bank and monetary policy – is the right way ahead for New Zealand. Concretely, I’ve suggested that the Bank be required by law to publish periodic answers to Bernard Hickey’s question – what is full employment, what is the (estimate) NAIRU?

Finally, I was interested in the Governor’s evasiveness when asked about possible statutory changes to the provisions in the Reserve Bank Act that currently make the Governor the sole legal decisionmaker. It is fine to emphasise that in practice monetary policy decisions have always been made in a collective environment – whether the Official Cash Rate Advisory Group in the past, or the current mix of the Governing Committee and the Monetary Policy Committee. But we don’t have rules and laws for good times and when things are working well. And, as it happens the Bank and Governor haven’t covered themselves with glory in the last seven or eight years.

The Governor simply avoided answering the question of whether the law should be changed, even if only to cement in the collegial practice. Since (a) the Governor is leaving shortly, and (b) the Minister of Finance has commissioned advice on the issue and Labour (and the Greens) are campaigning for change in this area, it is hardly as if letting us know his views would tread on taboo territory. Perhaps to do so would have been to acknowledge that in no other central bank does one unelected person – a person selected other unelected people – have so much power, not just in monetary policy but in financial regulatory matters. It is something where change is well overdue.

Challenged as to whether legislative reform in this area might not enhance transparency (eg publication of minutes, or even the airing of alternative views), the Governor fell back on his old claim that the Reserve Bank is one of the most transparent central banks in the world. That simply isn’t so. It scores well, as I’ve put it previously, when it publishes material on stuff which it knows little or nothing about (the outlook for the next few years, where its guess is as good as mine, and none of the guesses are very good). But it is highly non-transparent when it comes to the stuff they do know about. Thus, we don’t see any of the background papers that go into the OCR deliberations (although I did once use the OIA to get them to release 10 year old papers), we see no minutes of the deliberations, no record of the balance of the advice the Governor receives. And competing views (on the inevitably uncertain outlook, and the right policy stance) are not aired at all. That is a quite different situation from what prevails in many other advanced country central banks (although of course there is a spectrum, but we are at one end of it).

As another telling example of how untransparent thiings are in New Zealand, I was reading the other day a piece by John Williams, the very able head of the San Francisco Fed, and a member of the FOMC. In the US system he is a pretty senior guy – not Janet Yellen, but not just a Reserve Bank chief economist ever. His widely-distributed article was devoted to advocate a material change in how US monetary policy is done – abandoning inflation targeting in favour of price-level targeting – to provide greater policy resilience in the next serious downturn. I’m not persuaded by Williams’ case, but what struck me is how open the system is when such a senior figure can openly make such a case. The markets didn’t melt down. The political system didn’t grind to a halt. Rather an able senior official made his case, and people individually assessed the argument on its merits.

The other bit of the paper that struck me was this

Now that we’ve gotten the monkey of the recession off our backs, we have the luxury of being able to look to the future. This presents us with the opportunity to ask ourselves whether the monetary policy framework and strategy that worked well in the past remains well suited for the road ahead.

Such introspection is healthy and constitutes best practice for any organization. In fact, the Bank of Canada has already shown us the way. Every five years, they conduct a thorough review of whether their policy framework remains most appropriate in a changing world. This is an exercise all central banks should undertake, including the Fed.

I’ve made this point myself previously. The Bank of Canada is very open about these reviews they conduct. By contrast, in New Zealand, it is still a struggle to get from the Reserve Bank and Treasury papers relating to the lead-up to the 2012 PTA, and all the (limited) deliberations then took place behind closed doors. We will have a new PTA early next year, and we know – from other documents Treasury has released – that Treasury had some sort of review underway and almost completed before the Minister decided to delay the appointment of a permanent Governor. But given that PTA is the guide to the management of the key instrument in New Zealand short to medium term macro policy, it would be both appropriate, and more truly transparent, for much of the background thinking and research to occur openly. It is too near the election now, but a jointly hosted conference every five years reviewing the experience with the PTA and looking at alternative options (even if none ends up adopted) would be one feature, in our system, of meaningful transparency. We have very little of that at present.

(And, sadly, we’ve never seen anything from our Reserve Bank on the possible challenges if the practical limits of conventional monetary policy are exhausted in a future severe downturn).

It will be a challenge for the new government to lift the performance of the Reserve Bank in future. It would be easier to make a strong start in that direction by legislating first to make the appointment of the Governor a matter for the Minister of Finance (and Cabinet) – as it is in most other places – not something largely in the hands of the unelected faceless Reserve Bank Board (which doesn’t even seem to manage well basic record keeping).

“As the Governor noted, they (and other people) always get their immigration forecasts wrong.”. This week I was told that the target time to process a specific visa was advertised as 25 days but because of lack of staff it is now taking 2 to 4 months. Much the same happened with my families visas a decade ago when 4 months became 7 months. My point being lack of adequate staffing is resulting in a delays that make prediction difficult. Like steering a super-tanker. Is it the same lack of staff that permits so many rorts – there doesn’t seem to be anyone checking that promises are kept: that students are studying instead of unloading drugs from containers and skilled migrants are doing skilled jobs?

These unnecessary delays in processing visas are likely to be skewing our potential migrants from high skill to low skill. A true talent may be unwilling to wait months to start work and choose to go elsewhere. Dr Eric Crampton of NZ Initiative has written about this.

LikeLike

Yes, there are those administrative problems, altho the problems macroeconomists face in predictions 12-18 months ahead tend to be of a different order (eg what impact will changes in student work rights etc have, how will the Aus labour market change etc).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Forecasting is an essential tool. It is not a mug that forecasts. It is lazy and a cop-out attitude to not forecast. This is another great reason why a Chartered Accountant should be the next Reserve Bank governor. The future is always uncertain but you build a model and you build a set of assumptions that derive your forecast. It is these base assumptions that is critical. You may get it wrong but with clear and written base assumptions then you can rationalise what went wrong and make course corrections where necessary.

LikeLike

We are probably mostly talking at cross purposes he. Today’s OCR decision inevitably has some implicit or explicit forecasts behind them (as any firm’s business decision today does). The RB gets different in that it tries to projct what it will do 2 or 3 years hence. that is a fool’s errand – now even more so than most times, as wedon’t know who the Governor will be,or what the Act or PTA will look like.

LikeLike

Re projected wage inflation and immigration, thought Box C was interesting:- “….employers [may] address labour shortages by increasing their hiring of lower-skilled workers, and investing more in training. Employers are also expected to increasingly look offshore for labour.”

LikeLike

That’s quite a drop in net immigration, is there any further reasoning available for that drop?

LikeLike

[…] a US context, I linked a couple of weeks ago to a speech by John Williams, head of the San Francisco Fed, openly exploring whether the Fed […]

LikeLike

[…] that the Fed shift away from inflation targeting, towards something more levels-focused. As I noted […]

LikeLike

[…] As I noted then […]

LikeLike