Over the weekend I was (as you do) dipping into the 1968 edition of the New Zealand Official Yearbook, in pursuit of some material I might write about later in the week.

As I flicked through the pages, I stumbled on a table showing labour productivity for the previous 12 years. It wasn’t an ideal measure. There wasn’t a good series of hours worked nationwide in those days, so this series was a measure of real GDP per person employed. But what really caught my eye was the numbers. Over only 12 years, labour productivity was estimated to have increased by 28.9 per cent. And this was in an era when experts, and official agencies, were starting to worry about New Zealand’s productivity growth, and to produce data showing that we were beginning to fall behind other advanced economies.

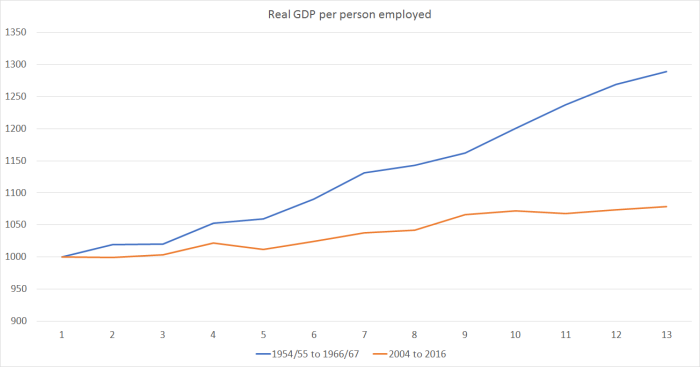

Here is the chart showing both the old data (for 1954/55 to 1967/68) and the same measure (real GDP per person employed) for the 12 years from 2004 to 2016. For the more recent period I have (a) used an average of the production and expenditure GDP measures, and (b) adjusted for a lift in measured employment of around 2 per cent in June last year, solely because of the change in the HLFS itself.

Over 12 years, they managed 28.9 per cent productivity growth in the 50s and 60s (with a fairly inward looking economy, with high levels of trade protection), and in our generation in the same period we’ve seen only about 7.9 per cent growth.

Of course, much of the slowdown is a common phenomenon seen across the advanced world, so this isn’t intended mainly as a stick with which to beat New Zealand governments specifically. But is a sobering reflection on how little material progress we, and other countries, are now making, relative to the astonishing progress seen in those post-war decades.

And, of course, we do have better data now. A rising share of part-time workers tends to dampen GDP per person employed. Here is real GDP per hour worked for the same modern period – ie 2004 to 2016.

Overall growth has been a bit stronger (12.1 per cent in total) on this better measure. But this measure also puts the New Zealand specific problems into sharper relief. We’ve had no productivity growth at all, on this measure, for four or five years. And that isn’t a global phenomenon, just a New Zealand one.

Could we manage 28.9 per cent productivity growth over 12 years again? It is only an average annual growth rate of a touch over 2 per cent, and the gaps now between New Zealand average productivity and that in the leading OECD economies are so large (they are more than 60 per cent higher than us) that it really should be achievable. But it would probably require, as a first step, giving up the rhetoric suggesting that really everything is just fine in New Zealand, and starting to focus on measures that might make a real difference.

Given that we are now the worlds largest exporter of milk with 10 million cows with $10 billion in milk exports, the growth in the primary produce has reached its limits. I guess you could have an argument that 70 million sheep back then is more productive than 10 million cows today perhaps?

LikeLike

10 Million Cows?? I think not! Maybe 6.5 million at a pinch incl male calves…

The problem is not the number of cows per se… is the value that is added post the farm gate before the product is sold… if the bulk of what the ‘end product’ is, is bags of milk powder then you haven’t added a lot of value… more cows does not increase productivity per se… more $$ per ton of milk solids does…

LikeLike

Could it be a problem that whereas back in the 1950s and 1960s manufacturing — albeit highly protected — constituted a much bigger proportion of our economy than it does today?

It strikes me that it’s much easier to make gains in productivity in manufacturing than it is to make gains in productivity in importing stuff and distributing it around the country.

LikeLike

100% use of robots to completely replace any need for human intervention would be the utopian world of productivity. The problem with too much use of robots is that robots have very little spillover into the local population. Robots do not eat, drink, no leisure or rest time. The local community would suffer as more robots are introduced into the workplace. Wealth will be isolated to the few shareholders with very little spillover into the local communities.

The government will need to start to look at a Robot tax in order to continue to provide for the growing mass of unemployed people.

https://qz.com/911968/bill-gates-the-robot-that-takes-your-job-should-pay-taxes/

LikeLike

Could we have 2% productivity growth again? I would have thought so.

Urban land use is a big part of the economy, so if the central govt forced/cajoled local govt to free that up, that would have a huge impact.

Oligopolies in domestic products and services are strong, so if we strengthened the commerce commission we would see more competition there.

The domestic sector has lower productivity growth than the external sector, so if we increased national savings and reduced the need for infrastructure spending, the exchange rate would fall and that would increase productivity.

The private sector has faster productivity growth than the public sector, so if we keep the public sector at a reasonable level.

None of these things are impossible for a strong government. The answer as to why these things have not been done is that in the context of a 3 year election cycle, productivity doesn’t win votes, whereas avoiding controversy does.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The NZ Wool Boom was one of the greatest economic booms in the history of NZ, the direct result of USA policy in the Korean War.

As a result of the Korean War, the US sought to buy large quantities of wool to complete its strategic stockpiles. This led to the greatest wool boom in NZ’s history, with prices tripling overnight. NZ experienced economic growth such as has never been seen again since.

Echoes of the boom reverberated into the late 1950s, by which time a record number of farms were in operation

Then suddenly, the export price of wool fell by 40% in 1966

LikeLike

Apologies – the above is a complete knock-off from Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_Zealand_wool_boom

LikeLike

Yes, the terms of trade were a help in the 50s and mid 60s (although even then there were nasty cyclical corrections). But recall that (a) this is real GDP I’m quoting (not purchasing power from higher prices, (b) official data at the time suggests that over the 54/55 to 67/68 period as a whole the good terms of trade didn’t inflate real purchasing power further, and (c) during this period, productivity growth in NZ was falling behind that in other advanced countries

LikeLike

I’m guessing the biggest gains were in in agricultural productivity.

We started aerial topdressing in 1949 – an integral part of the ‘grasslands revolution’;

https://envirohistorynz.com/2009/11/29/the-grasslands-revolution/

And there were productivity advances in milking shed designs;

http://www.no8rewired.kiwi/nz-inventions/rotary-milking-shed-and-herringbone-shed/

A farmer once told me about going to the US to teach their dairy farmers how to train cows to back up for use within the new Kiwi invented rotary shed design.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Assuming availability of a time machine, tend to think a worker in the 60’s would happily trade in the then productivity growth rate for today’s level of real GDP per person employed (especially if they were allowed to take their house and youth with them….)

LikeLike

I’m sure that is typically true. The comparison I’m highighting is one of growth rates, not levels. In those days, real living standards were increasing by a quarter in only 11 years or so.

LikeLike

…indeed; just tend to think the focus on current (low) productivity growth rates somewhat overlooks cumulative gains.

LikeLike

Fair enough……we are a great deal better off than (a) almost all Africans today, and (b) our own great grandparents. Then again, French and Germans – whose great grandparents were much worse off than ours (as well as being overrun by wars on their own territory) – are now materially better off (in economies more productive) than we are.

LikeLike

There has been some fundamental changes to the nature of our (and other developed economies) economy over the decades since the 50’s. The rise of the services sector not the least.

I can see some sectors making massive increases in real productivity over the years – agriculture, building (despite the counterproductive effects of increasing complexity and regulation) manufacturing and so on. But this service economy, now apparently 70% of the total, I can’t understand that.

How do you measure the productivity of a professional rugby player. Would we be better off financially by changing to seven a side? The other eight could be aged care workers or something. What possible difference would it make.

We used to make our own clothes and manufactured goods, we now import those and mechanisation has hugely increased productivity in primary and secondary industry. So what the hell is everyone so busy with now that we “have to” import workers. How come we are so busy being Fonterra head office seat warmers, dog groomers or tattooists or the thousand and one fluff type non jobs, many of them highly paid yet we can’t pay our farm workers a decent wage reflecting their working conditions, danger and contribution to our wealth and well being? You really do have to wonder about the whole thing and where its going.

https://rwer.wordpress.com/2017/04/30/economics-is-a-form-of-brain-damage/

LikeLike

Some my remember SMP (Supplementary Minimum Price scheme). Relatively fixed number of farmers, relatively fixed amount of land, sheep numbers peaked at 72 million in 1975, now what are they 27 odd million. Sheep per farmer and sheep per hectare have taken a productivity hit since those days.

We have some of the best farmers in the world,but there is only so much education you can stuff into them, and only so much variation in technology improvements that can be taken up, the land supply is fixed so productivity gains are minimal at this business level. At the margin some land can be shifted to other more productive uses, winery from grapes to bottle to market for example, or kiwi fruit, or avocadoes.

I guess at the next step up the chain from the farmer are the meat works and Fontera where technology offers substantial gains provided you can address demand for your product, sophisticated cheeses rather than milk powder, or branding such A2 milk for children to China.

The rest of NZ business tends to follow the “jobbing” model of production where it is hard to achieve massive gains.

Who can forget Helen Clark doubling the size of the Public Service, that probably halved productivity in this sector (an oxymoron anyway), and given the stifling rules and regulations from them and their cohorts in local government we are still paying that price.

Like the rest of the developed world productivity improvements have stagnated as our model has shifted to services. Like in retail you have to have a certain amount of staff to man the shop, a certain number to man your hotel…try cutting numbers and service suffers.

As for David’s lament above, “why cant we pay our farm workers a decent wage” simple, in dairying they are because of market forces to a degree but most of our famers are price takers at the farm gate competing on the world market. Hard to pay great wages when that market doesn’t want your lamb or wool, or youre competing against dairy produced in the subsidised EU model.

The past is no guide to the future really as again you could argue that Roger Nomics was a disconnect with the past…

LikeLike

Thank you for your response Ross, my questions were really rhetorical so I’ll tell you what I think is occurring.

The changes in farm workers relative remuneration is really a response to the finacialisation that has occurred to the economy over the past fifty years.

The farm debt has increased dramatically as the farms price has risen in response to its potential for capital gains and productivity gains. Even with our current low interest rates the average dairy farm needs to find about $200,000 per year in interest costs. An extra 10 or $20k for the farm worker shouldn’t be too much of a problem you would think. The farm worker is being squeezed to pay the bank interest. Interest costs directly caused by the need to pay the higher capital cost of the farm. Any profitability gain is magnified ten or twenty times into inflating the farm value, farms that are now among the highest priced in the world. The benefit does not flow to the worker; quite the opposite in practice. The farmers say “we can’t find worker”s and “our” government responds with a loose, fraud riven worker immigration policy targeted at third world countries with the effect of lowering pay even further. The neo lib free-marketeers in government are quite prepared to throw the people under a bus to preserve the interests of the big foreign owned banks.

Our young guys that were keen on farming would often start with basic farm work, milking etc. The plan being to save up and buy a herd so you could become a share milker. These farm workers today need to save up to buy their next pair of Redbands , there is no possibility of progressing to farm ownership and the whole rural sector is facing a social and economic upheaval. Farms pay more to the banks than the farmer and the worker both make in income, the money leaves the area (and the country to a large extent) and the district and its people are further impoverished.

Curiously the farmers can afford to pay extremely high wages, just not to the workers out in all weathers at all hours with a high risk of disease and injury, The Fonterra head office is a magnificent edifice with a highly paid staff in great comfort. Fonterra have a total of four thousand staff there and elsewhere on over $100,000 a year and some on over a million. No one is quite sure what they do or achieve but I bet she’s a pretty sweet number. An urban technocratic elite and the banking system have garnered all the surplus from the productive side of the economy (30%) and I think that is a very worrying trend as far as our long term future is concerned.

This whole dynamic is visible right through the economy Debt is high but has to keep rising; the economy needs to be continually juiced with rising credit/debtor or it will collapse. Private sector debt is approaching double the size of our economy and rising at double the rate of growth in the economy. We now have one eighth of our annual turnover (or GDP) a year (that’s $30,000,000,000) flowing into our economy from private sector debt expansion. Sustainable, not but take that away and it’s pretty much game over.

I had better stop but trust you can see an alternative explanation.

http://www.nzherald.co.nz/opinion/news/article.cfm?c_id=466&objectid=11622745

Click to access dairynz-economic-survey-2014-15.pdf

LikeLike

Hi Michael,

I know you’ve posted much commentary over time on the NZ productivity puzzle.

I incidentally came across an article on the Baumol cost disease that theorises why productivity is such an issue. Are you aware of this theory and if so whats your take for NZ?

https://www.vox.com/new-money/2017/5/4/15547364/baumol-cost-disease-explained?utm_source=pocket&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=pockethits

LikeLike

It is a nice article, and it is clearly an important phenomenon across time. I’m often interested reading books about periods say pre WW1 when poor students or struggling artists (eg Hitler in Vienna) could go to all manner of classical concerts, something that would be unaffordable for similar today.

I don’t think it explains anything about cross-country performance (although concerts probably should be cheaper – absolutely and relative to other items – here, all else equal, that in a higher productivity OECD economy), nor does it necessarily explain much about aggregate productivity (after all, we still staggering productivity gains in things that used to be very labour intensive – eg retail banking, where once people queued at the bank on Friday lunchtime for their weekend cash).

The interesting question – tho not necessarily one macro economists can shed huge light on – is which things are inevitable highly labour intensive, and which aren’t. Haircuts may well be, and live symphony concerts too. But as the article notes, taxis probably aren’t. Education and health probably have to be thought of at a much more disaggregated level. Much of medicine is very capital intensive, and there are big opportunities for productivity gains. But for the time being, one blood test still takes one nurse.

LikeLike

Michael,

this might be of interest http://voxeu.org/article/great-divergences-wages-and-productivity

LikeLike

Thanks. Looks very interesting. That said, my unease about the literature built on this productivity-dispersion thesis (including the Productivity Commission’s report here last year), is that we just don’t know what is normal, because there is no pre-2000 data (or so it appears).

LikeLike