How natural resources contribute to the prosperity of nations is much-debated. There is little doubt that a) natural resources can be wasted, mismanaged etc, such that a country well-provided for by nature still ends up pretty poor (Zambia is my favourite example, partly because I worked there), and b) that it is perfectly feasible for some countries to do very well indeed with little in the way of natural resources (one could think of Singapore or Japan, but also Belgium or Switzerland). The quality of the human capital of the people in a place, and the “institutions” that are put in place or sustained, make a huge difference. Location looks as though it might matter too.

But equally, it is easy to think of countries where it is pretty clear that natural resources have made a great deal of difference indeed in lifting the economic prosperity of the nation. One could think of Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Brunei, Equatorial Guinea and so on. It isn’t natural resources in isolation that makes them rich – Iraq and Iran still manage to mess themselves up – but in combination with some basic level of property rights, institutional quality, and human capital (native or imported) the natural resources have lifted living standards in such countries above levels that could otherwise readily be explained.

The quantity of natural resources in each country is fixed. That doesn’t mean that what can be done with those resources is fixed – able people and smart technologies find more efficient ways of extracting the resources or utilising them. We’ve seen that in New Zealand with the growth of agricultural sector productivity over 150 years or more. But the fact that the endowment is fixed means that each additional person added to the country reduces the average per capita value of that endowment. If the natural resource stock is small to start with, it isn’t a point worth bothering about (and so a lot of economic models largely ignore fixed factors). But if it is a large part of what an economy produces, and exports, it can matter rather a lot. It is why I’m unconvinced that rapid immigration policy driven population increase makes a lot of sense in New Zealand or Australia, where the overwhelming bulk of what we sell abroad is natural resource dependent. The point is more immediately pressing in New Zealand – where we haven’t uncovered major new natural resources for a long time – than in Australia, but is no less conceptually relevant there.

In this post, I wanted to illustrate the point by looking at the experience of Norway and Britain with North Sea oil and gas. The oil and gas were always there, but weren’t known about for most of history – and even if they had been known about, it wasn’t until offshore drilling and processing technology got to a certain point that the resources had much value. By the 1970s, Britain and Norway were beginning to get into oil and gas production.

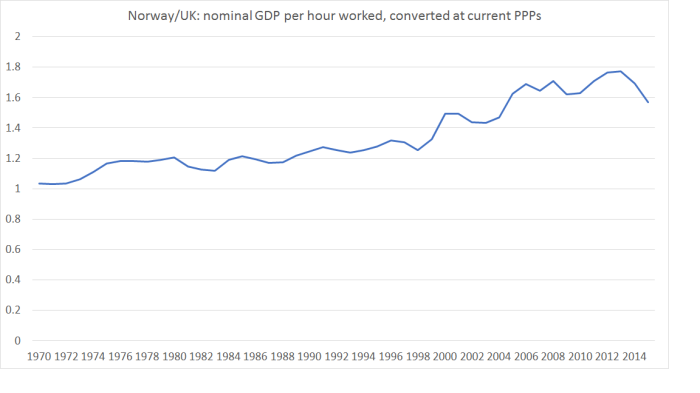

Britain and Norway were both advanced economies in 1970, drawing on the skills and talents of their people and growth-friendly institutions and cultures. Natural resources probably matter a bit more in Norway, but oil and gas weren’t then among those resources. And in 1970, OECD data indicate that GDP per hour worked in the two countries (converted at PPP exchange rates) were about the same. As it happens, GDP per hour worked in New Zealand then was around the same level.

These days, by contrast, GDP per hour worked in Norway is around 60 per cent higher than that in the UK (which is in turn quite a bit higher than New Zealand’s). Norway has among the very highest material living standards of OECD countries, and the UK is still in the middle of the pack.

These days, by contrast, GDP per hour worked in Norway is around 60 per cent higher than that in the UK (which is in turn quite a bit higher than New Zealand’s). Norway has among the very highest material living standards of OECD countries, and the UK is still in the middle of the pack.

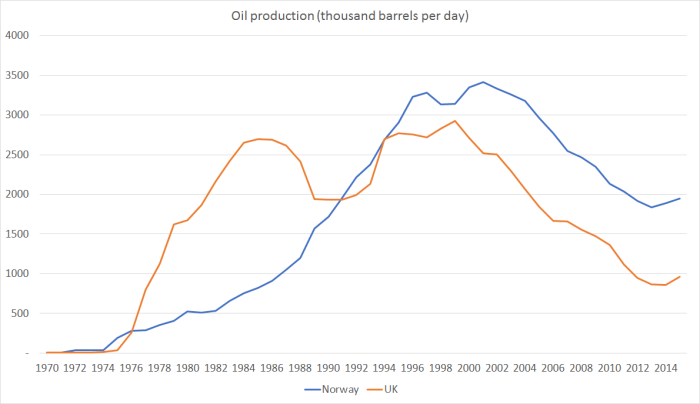

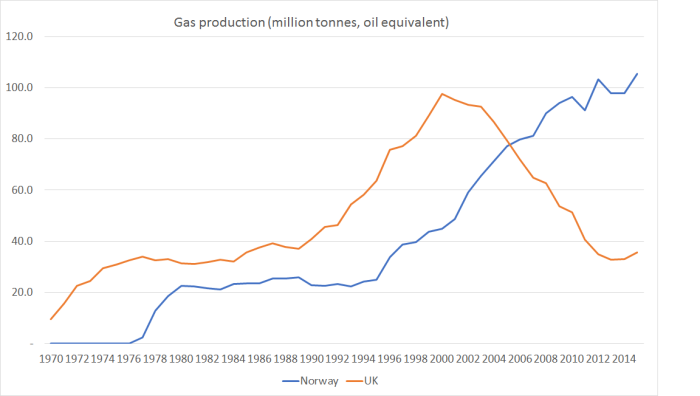

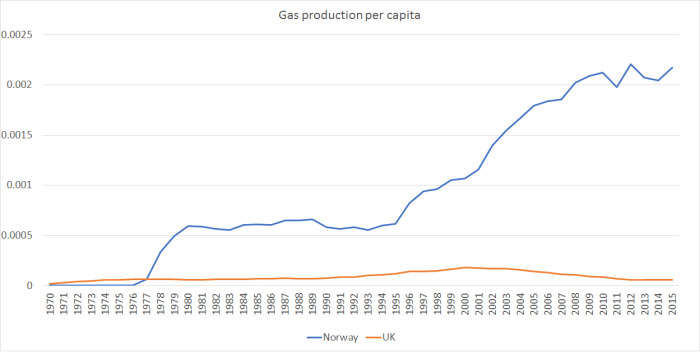

Here are the charts for total oil and gas production in the two countries since 1970, using data taken from the BP Statistical Review of World Energy.

First oil

And then gas

Over the 40 years to 2015, the two countries each produced roughly the same amount of oil and the same amount of gas.

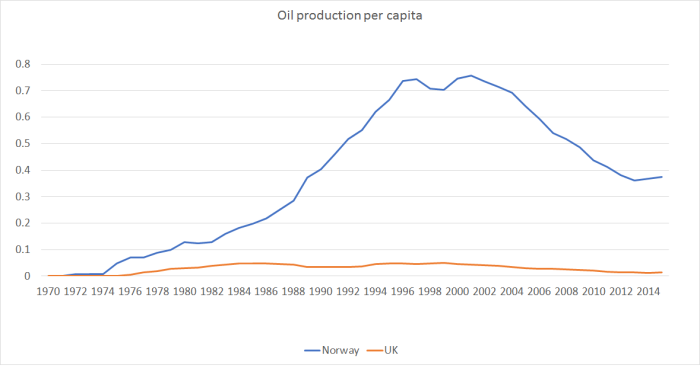

There are all sorts of differences between the two countries. I’ll come back to some of those, but the first I wanted to emphasise was population. Norway now has around five million people, and the UK currently has around 65 million.

Here is per capita oil and gas production for the two countries.

That “windfall” – the discovery of large recoverable oil and gas resources – made a big per capita difference in lightly populated Norway, and not much of one in heavily-populated Britain.

Determined sceptics might argue that it is all a mirage and that somehow Norway would have got to its current living standards anyway. If I was focusing on GDP per capita they could, for example, point out that in Norway a materially larger share of population is employed than in the UK. But, as it happened, I was focusing here on GDP per hour worked (and if anything, employing a higher share of the population should probably lower, at least a bit, average output per hour, if the less productive people are the last to be draw into the workforce). As it happens too, the employment/population gap between Britain and Norway is narrower than it was in 1970.

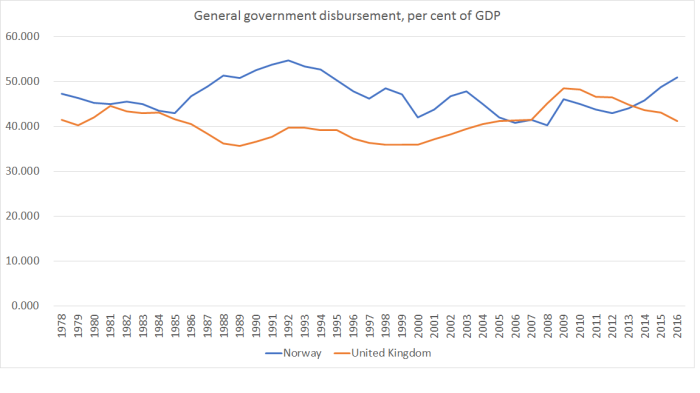

Perhaps too people might set out looking for areas in which Norwegian policy is superior to that in the United Kingdom. But there isn’t much to find. As a share of GDP, for example, government spending in Norway has typically been larger than it is in the UK.

And I went through the structural policy indicators released last week as part of the OECD’s Going for Growth. Norway isn’t badly run by any means, but on a majority of the indicators Norway scores less well than the UK.

Location probably favours the UK as well – the south of England is very close, and accessible to, the high productivity populous countries of France, Belgium, Netherlands, Germany. Norway isn’t remote – certainly not by New Zealand standards – but it isn’t quite as advantageously located for prosperity as the UK is.

In sum, don’t think any dispassionate observer would doubt that oil/gas – combined with the responsible management of the revenue – is what explains Norway’s rise over the last few decades to the top of the OECD league tables. And if, by some historical chance, there had been 65 million people living there, rather than the five million who actually were, it just wouldn’t have made very much difference. For the UK, the oil and gas were a “nice to have”. For lightly-populated Norway they made a great deal of difference.

For New Zealand, for whom extreme remoteness is a given, and where fixed natural resources make up so much of our export earnings, it is something to think about. There is a reasonable alternative story to tell under which the average New Zealander would have been better off – given the current state of global and local technology etc – if there were three million of us not 4.7 million. Perhaps that would have been the case, if we hadn’t restarted large scale immigration after World War Two.

My take Michael on New Zealand’s economic model of focusing on primary resource dependence while running a high immigration policy -is I agree with you Michael -it is logically inconsistent. Our ‘she’ll be right’ attitude has blinded us to the long term consequences.

I have a look at primary resource dependence in Canterbury in the below link. I probably take a different tack from you Michael -I think we have gone past the point as a country where we can look to primary resource production for our future economic activity -we need a new model.

View at Medium.com

LikeLiked by 1 person

We are no longer Primary resource dependent. We are now more increasingly tourism and international student dependent and immigration is a by product of that increasing tourism and international student dependence.

But yes we do need foreign pickers for our agricultural produce but that impact is miniscule compared to the needs of the average tourist and international student.

LikeLike

“We are no longer Primary resource dependent”

Well that’s a relief and a blessing I’m sure GGS. You mean we can shut down dirty dairy, our rape and pillage of the seas, ugly polluting mining, the damming of our magnificent rivers and end filthy fossil fuel production?

Who would have guessed that a few tourists and third world “students” could bring such bounty, wealth and prosperity to we lucky Kiwis. It might be better to keep quiet about it though – those Aussies will be stealing our cunning plan. Never forget Phar Lap and Split Enz!

LikeLiked by 1 person

As I pointed out last week, services exports are bang on the average share of GDP for the last 30 years, and well below the peak (about 15 years back). But in any case, i argue that most NZ tourism is natural resource dependent – they don’t come for the wonderful art galleries, cathedrals, or monuments to world power, but for the green and wild land.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Michael, Tourism and international students export GDP would always be bang on average as I have already pointed out to you. The reason is the $20 billion that tourists and international students spend is directly injected into the local economy which directly results in an equivalent increase in local GDP. It stimulates domestic GDP from the workers being employed that will then spend in the local economy. That $20 billion directly translates to wages and salaries of chefs, waiters, prostitutes, baggage handlers and cleaners that will go onto buy in the local shops and stimulate local GDP in services, consumption and housing.

LikeLike

Exactly, they come for the green and wild land. Not to see the millions of tons of cow dung, polluted streams, chemical wash, algae bloom from leaching from cow dung, get skin cancer from ozone depletion from cows methan gas emissions.

LikeLike

Don’t forget the most visited place in NZ is not your average green and wild location. The most visited place in NZ is still Auckland, with 18 million inbound and outbound passengers every 12 months. Let’s stick to facts rather than rhetoric.

And it is 3.5 million visitors not just a few. That number is 4 million this year and then the next target is 7 million.

Below is Australia’s foreign visitor numbers. Yes they have a similar immigration targets to service this many tourists.

“There were 725,800 visitor arrivals during January, an increase of 17.0 per cent relative to the same period of the previous year.

This brings us to 8.37 million visitor arrivals for year ending January 2017, an increase of 11.4 per cent relative to the previous year. This represents an extra 853,000 visitors on the previous year. ”

http://www.tourism.australia.com/statistics/arrivals.aspx

LikeLike

THanks Brendon. I enjoyed, and largely agreed with, your piece. I’m not sure there is much between us. I’m sceptical that many non natural resource based industries will prove sustainably viable in NZ (people will found smart companies, and then they’ll be more valuable/productive abroad. With a flat population – what we’d have typically with my proposed immigration policy – we’d have a much better chance of some of them proving viable, and of productivity growth in natural resource industries being sufficient to produce pretty good incomes (better than now relative to the OECD) for the people now here. Probably not as good as if, say, we’d stopped at 3m, but not bad. And that is even if we take seriously the environmental issues. We are after all still discovering what products grow well where in NZ – with 175 years of history, not a couple of thousand – and we know that there is plenty of land in NZ that has higher value primary uses than dairy.

LikeLike

Yep, like Branson said the other day. Grow dope and make pills to sell to the world. It grows so well here all over. But do we think that the govt. and all the goody two shoes will ever manage to get their minds around this.

Other plants that can do the same. Hemp is one, i.e. the one with no bang in it.

LikeLike

Yes, apparently our insects are also of premium quality.

In a world where livestock contribution to CO2 emissions and global warming is a serious issue, it makes sense to look at other sources of sustainable food. Farming insects can produce up to an order of magnitude more protein per unit land area, with a much lower environmental impact than farming cattle or sheep. Anteater’s mission is to “accelerate the advent of sustainable agriculture”. And clean, green NZ could become a premium supplier of edible insect products, if Anteater have any say in the matter.

https://sotw.nz/tag/startup-weekend/

LikeLike

Nice article. First I’d heard of Sam Mahon’s latest project – so I Googled it and it looks like it is going ahead. Is he still seeking donations?

There are some councils doing good work in an attempt to wean their ag communities off cows/price taking commodities and onto higher value, niche products. Tararua for example;

https://tararuacropping.wordpress.com/

We would have a wonderful cropping/ag future if only we could find a way to fund ourselves out of the debt that cows have wrought on us. High volume/low margin – with levels of both human and environmental stress never seen before in NZ. Animal protein it seems has all the hallmarks of a sunset industry. We must be mad.

LikeLike

In paragraph 2 you make the statement ‘Iraq and Iran still manage to mess themselves up’ How do you justify this, I thought that they have both been invaded.

LikeLike

Iraq was pretty messed up pre 2003, or even pre-Saddam, relative to say Saudi Arabia and Kuwait. Iran invaded? By Iraq I guess, but that was a long time ago now. They’ve largely made their own mess since.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree, I think the decline started with the very first Christian Crusades into Muslim lands pretty much destroyed a very high level and productive Muslim civilisation, many of its great cities and libraries burned and looted to enrich the Crusaders.

LikeLike

I’m guessing nz production from our natural resources (farms) is probably similar to the UK. So rather than arguing that if we had a smaller population our gdp per capita would be higher, the opposite could be possible ie. lots more people and production from our natural resources would be a smaller proportion of gdp. As I said yesterday our distance to Asia is probably similar to the americas. So why not think we can succeed?

Perhaps our issue is farming is currently such a big and successful part of our economy that nothing much else gets a look in.

Someone will end up making artificial meat and milk one day, then we’ll have to look at alternatives.

Or perhaps we’ll all emigrate.

LikeLike

My hypothesis would be “emigrate” – not everyone, of course (there is a famous paper on Why People Stayed in east Germany, even after 1990) but enough. After all, that is what has already been happening for the last 40 years without those inventions.

Yes, we might be as close to Asia as California is, but California is part of a continent of 500m people, and east Asia is home to a couple of billion,. and we are pretty much alone down here. Smart companies are and will be created here, but mostly they’ll be more valuable based somewhere else (unless they are drawing on something location specific – ie some natural resource or other).

You could be right that 100m people here would transform GDP pc prospects for the better, but it a) seems like an enormous risk, and (b) it would leave whatever entity was here no longer “New Zealand” as it has been for the last 150 years or so. And I can’t see why we – existing NZers – would want to try that.

And of course we’ve tried the “get bigger” strategy (on a smaller scale) for decades now, with no sign of it working.

There aren’t many people in Hawaii or Iceland or the Falklands or Greenland either.

LikeLike

Speaking of Iceland, have you ever compared NZ with Iceland economically? To me it seems NZ and Iceland are quite similar – largely resource based (Iceland has large fisheries and energy resources – think things like aluminium smelting), very remote; and yet, with only 300,000 people it supports a GDP per capita far in excess of NZ ($46,000 per capita vs $36000 for NZ, thereabouts), with commensurate high living standards. Imagine trying to crowd half a million people into Iceland to see what would happen.

Would be curious if you had any thoughts.

LikeLike

I haven’t done anything systematic on the NZ/Iceland comparisons, but my impression is similar to yours. At one stage the biggest point of comparison was our large foreign debts – at one stage at the RB I sent one of my staff there (happened to be in Europe anyway) to have a look.

Of course, one difference is the Iceland used to be quite poor – esp say compared to the NZ of 100 years ago.

LikeLike

Australia’s land mass is similar to the USA and New Zealand’s land mass is equivalent the U.K. So not exactly the lack of land or natural resources for a larger population.

LikeLike

Is location that critical? Surely transport costs are declining. (Explaining why it is viable to export high value timber as logs or pseudo-logs for other countries to process).

I suspect moving lamb from North Wales or Scotland to the London market may be similar to the cost of shipping it from NZ although lead times would be worse. After Brexit the paperwork for moving from Calais to London will be similar to Christchurch to London.

Technology helps – it costs nothing to see in real time, full vision our baby-granddaughter waking up and gurgling in PNG but 10 years ago it cost a fortune just to phone.

LikeLike

“that critical”? In many ways, you wouldn’t think so – and for basic goods it isn’t. I remembered being surprised a few years ago to learn how cheap it was to ship a container of lamb to London. So we can do quite well selling that sort of stuff. but the evidence suggests that for a lot of high tech manufacturers and services proximity (not just to markets, but to suppliers, value-chains, professional services etc) seems to be mattering more and more. I wish it were otherwise, but it seems to matter more than we have really appreciated, and so when able people in those sectors start companies here sooner or later most find they do better (are worth more) based someone nearer the centres of world economic activity.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Don’t forget all those cities with tens of millions of people and countries like the US with hundreds of millions used to look like Auckland. I guess if you looked at the perspective of native Americans which I was told was fabled as high as 70million native Indians before the new migrants replaced their peasant lives with new migrant cultures and new technology completely decimating an existing native Indian culture in the process creating a great USA.

LikeLike

Interesting comparison Michael, if I read your analysis correctly you are basically saying Norway is a “proxy” for New Zealand, both of us have a population of approx. 5m. However we have totally different economic histories with Norway being a “nothing” country till 1969 and the discovery of oil. But at least someone was home and they invested wisely. Shades of why some nations choose to fail or rather in this case, succeed.

While some of your commentators indicate it is just a matter of “changing our model” I guess as simple as changing our undies in their minds, I see us being like Norway in 100 years. By that stage vast quantities of oil and gas will have been discovered around NZ, and of course will be economic to extract. But two things will have happened by then, we will be using other energy sources and have missed the bus, and the usual socio/political regime will be true to form “we will choose to fail”!

LikeLike

I wasn’t trying to draw detailed comparisons with NZ, despite the coincidence of similar population size. I was just trying to illustrate, this time with the Norway vs UK comparison, the way large populations can dramatically deplete the per capita benefits of similar-sized natural resource shocks.

200m people in Aus, and the mineral booms of the few decades would have been largely irrelevant. With 20m they’ve been enormously beneficial.

LikeLike

Yes I know that was the point you were trying to make but I ignored it as “reductio ad absurdum” as reducing our population to “1” would give the best result. Who in your economic model determines the optimum population to achieve the best ratio?

Besides natural resources aren’t finite, look at Australia, and look at the US, most commentators would have said the US had no oil or gas left, technology proved them wrong.

If we used your model on the US economy, and its anti immigration component, say in the late 19th century, America as we know it would not exist, as the Scots and Irish who built America would have stayed at home so the America could optimise its then pre Industrial takeoff “wealth” (or lack of it)

In my view you are trying to impose a static on a dynamic…does not compute 🙂

LikeLike

Two quick points. Natural resources are finite – but the actual quantum/value of those finite resources are often only revealed v slowly (as eg North Sea oil and gas).

Re the US question, yes I have toyed with the issue you raise. I guess my overall response is that I’m not trying to rearrange the world, just looking for insights that help explain why little old NZ was once the richest country on earth and is now so very so-so (clearly not poor, but a poor performing reasonably wealthy country). The US – or indeed the whole of the Americas – was a vast “new” continent (to advanced technologies etc). We are a couple of isolated islands. There is a variety of other points – some econ, some geopolitical – i could make, but the kids are summoning me to watch a movie!

(on the americas, if one wanted to be deliberately contrarian, one could argue that the average European who moved to the americas – and their descendants – might well have been better off not to have)

LikeLike

Bring in solar power, wind power, wave power and now you have an unlimited and infinite natural resource.

LikeLike

Some big assumptions there Ross. Sorry but natural resources are not infinite and the example you quote is misleading. US Oil production peaked in 1972 and almost equaled that output again in 2015 but with such a dramatic decline in return on energy required for extraction/production that the net energy return for oil is still significantly below the 70’s production. Such is the level of decline that copper at a mere 0.6% of ore is now being mined at places like Bingham Canyon Mine. We are very much scraping the bottom of the barrel in so many areas: water, fisheries (Northern hemisphere ships in the Antarctic Ocean?), fossil fuels and minerals. Technology may have some solutions but will they be affordable and scaleable to meet the needs and wants of the people we already have? Probably not I would suggest.

I wonder about the future consequences for places like the UK with a growing population and their need now to import energy, minerals, timber and food. Despite the many great things about the Brits (innovative, rule of law, education etc) I suspect it will become increasingly difficult for them to maintain their per capita wealth and income.

The growth of America is likely an unrepeatable example based as it was on some very exceptional circumstances – a huge country laden with resources combined with the means and need to exploit them, Europe in a series of turmoils and a constitution that facilitated and a belief that encouraged liberty, private property and wealth. Despite that they decided to restrict immigration to quite low levels at times. From 1941 to 1960 – a time of extraordinary growth in the economy and wealth of the American people only 3.6 million immigrants came in. Vastly less (per capita) than our current levels.

LikeLike

Thats where you are wrong. Some natural resources are finite. Others like solar, wind and wave energy is infinite. Increasingly our technology is moving into that space. Even a nice prime piece of meat is being talked about as being 3D printable.

LikeLike

Sorry. My mind was on the UK/norway comparisons, and so I was thinking about mineral resources. Some other resources are renewable – eg our pastoral/agricultural land – but still finite. Is anything infinite – God apart? I’d suggest probably not.

LikeLike

Finite as far as the current technology but as we adapt and improve our technology new sources become available. I believe Elon Musk’s target of inhabiting Mars is the next technological frontier so even the land mass once considered finite is now looking like its not.

LikeLike

Well, yes, as i noted in the original post the oil/gas always were in the North Sea, but (a) the countries weren’t aware of it, and (b) couldn’t have extracted it anyway.

If the Martian landmass really does come into play, i guess it won’t be very good for those countries with lots of land on earth.

LikeLike

I’m certainly not suggesting that the exploitation of natural resources should be the entirety of our economy. “Send off the ore/timber/crude oil and sit back and enjoy” is a sure recipe for failure but to increase your population at an exponential rate while relying heavily on those resources is a high risk strategy.

The middle east is clearly in population overshoot, masked for the present (in most parts) by some solid income from their oil resource. I can imagine things becoming extremely (more) unpleasant in that part of the world in the future. They have chosen to compound their looming problems with a medieval attitude to personal and economic freedom, democracy, women rights and a (dare I say it?) religion that rejected the enlightenment and continues to suppress much of modern scientific thought at great cost to their present and future.

LikeLike

If you look at the history of China. It was a great trading nation when it was open to the rest of the world opening the Silk Road into Europe. But when it started to become inward looking and adopted protection policies and closed its borders it decline rapidly.

LikeLike

Oooops sorry didn’t realise you would end up with the entire Paul Kirby site. Please delete as supposed to be just a link.

As for David Georges concern for the UK, and lack of natural resources, you only have to look to Japan, Singapore, Hong Kong, Germany (like the UK coal only) to see that thesis doesn’t fly.

If you read “Waves of Prosperity” by Greg Clydesdale it demonstrates how China, 12-14th Century, then India followed by the Spanish, followed by the Dutch, followed by the English advanced society by technical change and productivity improvements in transport (shipping) business practices etc. None of those countries had natural resources.

LikeLike

I will certainly be reading the Waves of Prosperity book, thanks Ross.

I don’t think anyone has suggested that countries can’t prosper despite few natural resources, well not with the global trade and supply chains we have today. The advantage of technical and military superiority allowing the acquisition of resources and empire was the usual M O in the past. Japan prior to WW2 a more recent example.

I used the example of modern Britain since that was the one that Michael had chosen but it would appear to fit the pattern of a collapsing power. It’s rise was spectacular. A highly innovative and industrious population + embracing science (the Enlightenment) + reasonable resources +, property rights + law and order = Strong economy with a powerful military leading to the first global empire with access to a seemingly boundless supply of labour and materials. Today, despite a massive financial sector parasiting on the global economy, the ballooning current account, private and public deficits and declining currency would tend to suggest that all is not well. Surely you can see that having a large population dependent on dwindling resources represents a relentless drag on wealth.

In Jarod Diamond’s “Collapse” the usual cause of societal collapse is resource depletion (sometimes associated with climate change) so there is plenty of history to suggest that blatantly exceeding reasonable limits of extraction represents a significant risk for the future. Doubling our population every 35 years (i.e. 2% growth) would require some very significant changes to the way we pay our way in the world and is therefore both risky and unsustainable. Actually 2% growth is totally unsustainable whatever we do.

LikeLike

Thats not correct, we are already proving that our NZ environment can sustain around 10 million cows and 30 million sheep. a cow eats and excretes wastes to the amount of around 20 people which is equivalent to handling the food and waste production of a 200 million population as sustainable. I can guarantee that an average person is smarter and more productive than a cow.

LikeLike

I referenced Jarod Diamond, a wee extract from his website:

how could any society fail to recognize that big problems are looming up, and why doesn’t the society take measures to alert disaster? It was surprise at this question that caused the archaeologist Joseph Tainter, in his 1988 book The Collapse of Complex Societies, to dismiss out of hand the possibility that complex societies could collapse as a result of depleting environmental resources. Tainter considered it implausible that complex “societies [would] sit by and watch the encroaching weakness without taking corrective actions.” But that is precisely what has often happened in the past, and what is happening under our eyes today. Hence my chapter draws up a roadmap of group decision-making, starting with failure to perceive a problem in its initial stages, and ending with refusal to address the problem because of conflicts of interest and other reasons. Chapter 15 considers the environmental policies of big businesses, many of which are viewed as, and some of which actually are, among the most environmentally destructive forces in the world today. But other big businesses are powerful forces for environmental sanity: why do some businesses find it in their interests to protect the environment, while others don’t? My last chapter lays out the dozen major environmental problems facing the world today, our prospects for solving those problems, and the differences between the dangers facing us and the dangers facing past societies.

http://www.jareddiamond.org/Jared_Diamond/Collapse.html

LikeLike