The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) is often loosely described as “the rich countries club”. It isn’t an entirely accurate description – there are several high income oil exporting countries who don’t belong (as well as places like Singapore and Taiwan), and some countries that are members (notably Mexico and Turkey) aren’t particularly high income. But it is a grouping of mostly fairly advanced fairly open economies (New Zealand’s been a member since 1973). And the organisation claims to be able to offer useful advice to countries as to how to improve their economic performance. I’ve become increasingly sceptical of that proposition, especially as regards New Zealand.

On a biennial cycle the OECD’s Economic and Development Review Committee (EDRC) meets in Paris to review each member country’s overall economic performance, and offers some specific advice both on general economic management issues and on specific topics agreed in advance between the secretariat and the country concerned. I wrote about the process, which draws on extensive staff work, on the day New Zealand was last reviewed in April 2015.

The next review is almost upon us. The EDRC is scheduled to discuss New Zealand on 20 April, so the draft text is probably already in the hands of New Zealand government agencies. The final text will presumably be released in late May or early June. This year’s agreed special topics are “Increasing Productivity”, and “Labour Markets and Skills”. The latter topic apparently includes the New Zealand immigration system, and when the OECD team came to Wellington last year I participated in a meeting with them, along with various government agency representatives, on some of the strengths and weaknesses of our system. Historically, the OECD tends to be very strongly pro-immigration – without much evidence for its benefits, especially in remote places like New Zealand – and I expect their treatment this time will again reflect that presumption, probably with some suggested tweaks at the margins. But, as often, the OECD might be able to present some cross-country data on the issues in interesting ways.

Quite what they’ll come up with to increase productivity could be more interesting. In many ways, New Zealand is a test for whether the OECD has much useful to say. For a member that was once among the richest and most productive OECD economies and now languishes a long way down the league table, New Zealand has been a bit of an embarrassment to the OECD. After all, we did an awful lot of what they suggested 25 to 30 years ago.

I’m writing about the issue because a few days ago the OECD released one of their flagship cross-country publications, Going for Growth. These documents often contain a lot of interesting cross-country comparative material – data collection and presentation is one thing the OECD defintely does well. But they also get specific, and have a couple of pages of economic policy priority recommendations for each country. Since the OECD must already have written their full substantive report on New Zealand for the forthcoming EDRC survey, one might have expected that the recommendations for New Zealand would be particularly incisive and well-focused, offering suggestions which, if adopted, would clearly help reverse our long-term underperformance. As they note, labour productivity gaps between New Zealand and the other advanced economies have continued to widen over the last quarter century. As the OECD’s own chart illustrates, real GDP per hour worked is now about 37 per cent below the average for the countries in the upper half of the OECD (these are countries from Luxembourg and Norway at the top, to Italy and the UK at the bottom).

So what does the OECD propose for New Zealand?

- Reduce barriers to FDI and trade and to competition in network sectors. Recommendations: Ease FDI screening requirements, clarify criteria for meeting the net national benefit test and remove ministerial discretion in their application. Encourage more extensive use of advance rulings on imports and improve the publication and dissemination of trade information. Sell remaining government shareholdings in electricity generators and Air New Zealand. Remove legal exemptions from competition policy in international freight transport.

- Improve housing policies. Recommendations: Implement the Productivity Commission’s recommendations on improving urban planning, including: adopting different regulatory approaches for the natural and built environments; making clearer government’s priorities concerning land use regulation and infrastructure provision; making the planning system more responsive in providing key infrastructure; adopting a more restrained approach to land regulation; strengthening local and central government emphasis on rigorous analysis of policy options and planning proposals; implementing pricing to reduce urban road congestion; and diversifying urban infrastructure funding sources.

- Reduce educational underachievement among specific groups. Recommendations: Better target early childhood education on groups with low participation in such education. Improve standards, appraisal and accountability in the schooling system.To improve the school-to-work transition, enhance the quality of teaching, careers advice and pathways, especially for disadvantaged youth, and expand the Youth Guarantee. Facilitate participation of disadvantaged youth in training and apprenticeships. Students from Maori, Pasifika and lower socio-economic backgrounds have much less favourable education outcomes than others.

- Improve health sector efficiency and outcomes among specific groups. Recommendations: Increase District Health Boards’ incentives to enhance hospital efficiency, improve workforce utilisation, integrate primary and secondary care, and better managed chronic care. Continue to encourage the adoption of more healthy lifestyles.

- Raise effectiveness of R&D support. Recommendations: Further boost support for business R&D to help lift it to the longer term goal of 1% of GDP. Evaluate grant programmes. Co-ordinate immigration and education policies with business skills needs for innovation.

The general goals seem fine, in as far as they go. And some of the specifics seem sensible enough too (others – more R&D subsidies, government encouragement of “more healthy lifestyles” – seem distinctly questionable). But could anyone with a reasonably in-depth understanding of the New Zealand economy and its performance over the last few decades, really think that that list, even if adopted in full, would really make a material difference in turning around New Zealand’s long-term productivity underperformance? I’m all for fixing the housing policy disaster, but when the OECD talks of the agglomeration gains that might make possible, have they actually looked at the dismal Auckland productivity performance over a period when Auckland’s population has already grown very rapidly?

It is also quite surprising what they don’t mention. Perhaps macro imbalances, such as our persistently high real exchange rate, or our (typically) highest real interest rates in the OECD, don’t easily fit in a structural policy document – although they are significant symptoms that a list of possible structural policy remedies needs to notice.

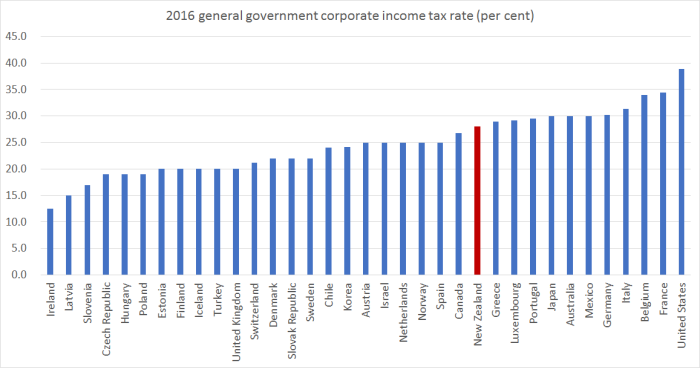

But the OECD does publish as part of Going for Growth quite a range of cross-country comparative data on various structural policy indicators. Even then there are puzzling omissions. There is nothing at all, for example, on immigration policy. And company tax is also missing. Here is the data from the OECD website on statutory company tax rates for 2016.

New Zealand is in the upper third of OECD countries – and with a company tax rate well above that group of countries (from the Czech Republic to Switzerland) at around 20 per cent. I’m all in favour of reducing FDI barriers, for example, but for many firms who might consider establishing here, the likely tax bill is probaly a more significant consideration. And I suspect it offers more payoff in improving productivity than the health system, whatever the merits of the specifics they propose there.

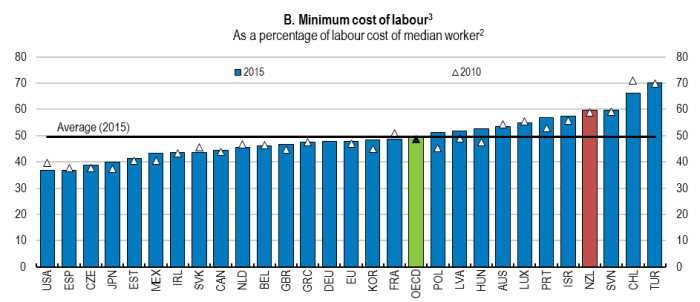

It was also interesting that the OECD does not mention our labour laws. It is well-known that our minimum wage is quite high relative to median wages/labour costs. In fact, the OECD again illustrate it in their indicator pack. This is their chart, and I’ve simply highlighted New Zealand.

It is a quite a stark picture, but doesn’t seem to be a priority issue for the OECD. Actually, I doubt altering the minimum wage laws offers very much on the productivity front, but even if one is simply concerned about disadvantage (as they very much seem to be) we know that getting people into jobs is the best path towards longer-term economic security. One needn’t go to the US end of this spectrum, but places like the Netherlands and Belgium aren’t exactly known as bastions of heartlessness, small government or whatever.

Overall, I think the list still suggests the OECD has very little idea what has gone wrong in New Zealand, and hence has little more than a generalised grab bag of ideas to offer in response – many no doubt quite useful in their own way, but mostly likely to be tinkering at the margins.

Out of curiousity, I had a look at what they had to recommend for the previous country on the (alphabetical) list – the Netherlands. It is an interesting country too. Productivity – GDP per hour worked – is above that for the group of countries in the upper half of the OECD. Indeed for decades productivity levels in the Netherlands have been very similar to those in the United States. Per capita income lags a bit behind, because Dutch people on average don’t work long hours each year (although the participation rate is high). But it is, by most counts, a very successful economy. Real GDP per hour worked is about 65 per cent higher than in New Zealand.

What does the OECD recommend for them?

- Lower marginal effective tax rates on labour income.

- Ease employment protection legislation for regular contracts and duality with the self-employed.

- Reform the unemployment benefit system and strengthen active labour market policies.

- Increase the scope of the unregulated part of the housing market

- Increase direct public support for R&D [even New Zealand spends more on this than they do]

Setting aside the OECD’s taste for R&D subsidies, it mostly seems sensible, plausible, and well-targeted. They seem to have a better idea what to offer an already rich and successful country in the heart of Europe, than they have to offer a once-rich now-underperforming remote one. For us, that is a real shame.

One can only hope that when the productivity chapter of the forthcoming New Zealand economic survey comes out, they can offer a more persuasive grounded set of recommendations as to what might make a real difference in reversing our decades of underperformance.

(For a more optimistic take on the OECD’s recommendations for New Zealand, see Donal Curtin’s assessment.)

“It is also quite surprising what they don’t mention. Perhaps macro imbalances, such as our persistently high real exchange rate, or our (typically) highest real interest rates in the OECD, don’t easily fit in a structural policy document – although they are significant symptoms that a list of possible structural policy remedies needs to notice.”

Yep.

LikeLike

Yet, our real interest rates and FX rates are ‘market’ determined. I think Michael argues this is due to continued population ‘demand shocks’; tend to think we are in debt to the rest of the world so we pay more; I’m not smart enough to prove that is the main issue but the bank receives more from those in debt than it pays to those with credit balances…

LikeLike

Yes, they are market-determined, but market prices are an outcome of actual and expected supply and demand forces, some of which are themselves the choices of firms and households, and some are more or less directly influenced by govt choices. For example, when govts increase their consumption of real goods and services, it tends to increase the real exchange rate and real interest rates. My argument is that our govt-controlled immigration policy has a similar effect – more visible than some places because we NZers choose only a modest national savings rate. A similar immigration policy in a country with a much higher savings rate – Singapore say, on both counts – will produce different results.

LikeLike

No, interest rates are monopoly determined by our Australian owned banks. Graeme Wheeler without proper research and no due diligence rushed a 60% LVR and 40% equity onto banks. In effect banks now have a substantial captive customer base who have borrowed on 80% LVR and 20% equity. This in effect prevents those customers to leave for another competiting bank to take advance of lower interest rates being offered. HSBC has been dutifully competiting and offering 3.99% interest rates but customers with existing banks are unable to shift due to Wheeler’s and the RBNZ interference with natural market forces. The Commerce Commission is simply not doing their jobs to ensure there is competition.

LikeLike

Indeed what is missing is also the OECD recommendations on cows.

In their first comprehensive report on New Zealand’s environment in a decade, the OECD’s environmental review team called for agriculture to be brought into the Emissions Trading Scheme and said the Government needed a plan for meeting its greenhouse gas targets, while still earning more from exports.

“New Zealand’s growth model, largely based on exporting primary products, has started to show its environmental limits, with increased greenhouse gas emissions, diffuse freshwater pollution and threats to biodiversity. A long-term vision for the transition towards a low-carbon, greener economy is necessary,” says the OECD report.

LikeLike

Thanks for your explanation. I had wondered who OECD where when their ‘Going for Growth’ was mentioned in the news. It would seem they mean wealth production per capita.

At present I’m more concerned by the sharing of the cake than the size of it. Assuming a fairly rapid depopulation in NZ my house would not be worth a million – more like a tenth of that but I would still have my house and when I die my children would have very little inheritance but then again they wouldn’t need it for getting onto the property ladder. And our problems with traffic, the homeless, pollution would dissolve. Maybe less real cash in the pocket for my working children but a better lifestyle. Can we persuade Bill Gates to move to NZ – that would up leave us all $20,000 better off.

Who benefits from growth? Can anything grow forever and what happens when growth stops?

LikeLiked by 1 person

of course in the long long run everyone benefits from growth – we live longer, have more and generally better “stuff” etc than our ancestors a couple of hundred years ago. In general, i reckon smartphones are overrated (says he resisting his wife’s injunction to upgrade the years one), but it access, in your pocket, to knowledge that almost all humans, in almost all history, we’d have found hard/impossible to find, as astonishingly cheap prices.

(which doesn’t mean i’m indifferent to distributional questions in the shorter-run).

If the choice were on offer – which it isn’t – of having Dutch productivity here and more unequal incomes/consumption then many would probably prefer to take that choice, because most/all of the people at the bottom would also be absolutely better off than they are now.

LikeLike

It is true I do not want to return to the lifestyle we had growing up in the 50s. (Although I expect we were as happy as children today).

The instinct for equality is deep. They have found monkeys will angrily refuse a treat if another monkey is offered a better treat.

The Smartphone is cheap; we do not need an increase in national wealth for everyone (except you and me) to have one. In the past valuable items were for the wealthy: things such as meat whenever you want it, books, transport, clothing. These are all now cheap and getting cheaper. But the tremendous improvement in living standards has everything to do with rewarding ingenuity, competition and cheap Chinese labour. None of these necessitate NZ to aim for growth. Compare growth in Auckland, stablity in Dunedin and decline in Oamaru – don’t they all have smartphones?

LikeLike

You should add a Ipad pro 13 inch and that will really make a difference to your day to day. You could spend the entire day on the beach and bring your office with you on that Ipad Pro 13 inch to do all your blogging and research at your finger tips, answer email without the eye strain of a small smart phone screen. The Ipad Pro connects to your smartphone so you can read and reply to all your phone messages and make video conference calls.

LikeLike

Thanks for the advice! 90% of the year sitting on the beach isn’t a great option in Wellington, but I get the gist……

LikeLike

You can also extend your battery output with accessories like powerbanks. I carry 2 power banks in my iPad pouch. Also pay for extra internet mobile data. It would be great when they have unlimited data for use outside of the home but at the moment you are limited to about 15gigabytes of data a month. You have hotspot wifi with your smartphone so you don’t need to have an extra mobile connection for your iPad.

LikeLike

Might be OK in Mt. Maunganui or Ohope but then you would need a deep pocket these days to buy the beach batch. Morgan might let you bunk in at his place.

LikeLike

I am just an ordinary fellow that has wandered my way through just over 70 years in NZ. No great qualifications of any kind, made a few dollars along the way and lost a few as well. Employed a lot of people spent a lot of money on goods and services and done quite a bit of time in service clubs etc.

I have never though the OECD had much to say that made sense or was particularly insightful and helpful to kiwi’s as citizens.

Indeed I often wondered where they were coming from and kinda decided that they parroted the latest Finance Ministers, Treasury and RBNZ brain farts. Seemingly not, it appears to be the other way around, though who knows.

I think actually we suffer grievously from short person syndrome. All our leading pollies seem to be short and suffer the necessary complex from being so which is why we we fail so miserably at having sufficient self esteem to tell these oversea’s control freaks that actually we don’t need/want their advice and that actually we have people with more perception of our needs than they can ever give. We just don’t listen and act for NZer’s. We bother ourselves falling all over the next greatest silly idea that makes pollies happy instead of making our countrymen and women happy.

I find that more and more we need a real dose of NZ First policy. Don’t you just hate that. But it is true.Kiwi’s seem n o longer to rate with our pollies. Hence all this immigration to our detrement.+

The latest trade figures show we are still going backwards despite the fact many Kiwi’s are working harder and harder and smarter but the govt, has us screwed.

http://www.stats.govt.nz/browse_for_stats/industry_sectors/imports_and_exports/OverseasMerchandiseTrade_MRFeb17.aspx

Surely its is time we got to grips with our exchange rate problem.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting idea about height and self-confidence. There is a known link between height and pay but I believe a much smaller correlation between height and intelligence. [The latter maybe related to the ability of a child to absorb useful proteins into body and brain.] Which leaves the link between height and pay which is somewhat similar to the gender pay gap. And there is a third correlation between good looks and pay. [I score on 2 out of 3 but unfortunately they are all minor factors compared to talent.]

If it was only immigration I might vote NZ First despite a total loathing of some of their racist supporters. If Winston promised to never say the word Chinese I just might vote for him. For example his attack on elderly Chinese immigrants getting superannuation after just 10 years in NZ – I know this can also apply to immigrants from the UK who been in 3rd world countries abroad for most of their working life. So a good point was lost on the public because of the racist over tones. I also totally disagree with their protectionist policies and their right wing populist attitude to law and order.

I have a friend who was present when Allan Bollard gave a speech and all he could remember of the occasion was his being very tall. And John Kenneth Galbraith was about 2 metres. I’ve never actually met an economist – are they unusually tall? They do seem to be predominately male – search Wikipedia for ‘famous economists’ and the first 32 were men.

LikeLike

The list of short noisy politicians and supposed leaders is endless. From rugby to Parliament there is no shortage of short ones vying to make themselves relevant by making a noise and telling everyone what is best for themselves.

Savage, Holyoake, Lange, Rowling, Muldoon, Cullen,Key, English, Bennet, Litlle et al.

LikeLike

Winston peters is not anti immigration. What he preaches is sustainable immigration. What it means is more of the human rights difficulties that prevent older people from joining their migrant children in NZ. But because we will continue with more and more tourists who need cheap and low skilled labour which are jobs New Zealanders do not want to do, industry will continue to require more migrant labour. Winston will not stand up to industry requirements. Therefore nothing really would change under NZFirst.

LikeLike

For rather different reasons, I’m inclined to agree with your final sentence. Winston was a senior minister in a coalition or confidence&supply agreement under the Nats in thre 90s and Labour in the 00s and, despite all the talk, did nothing material on immigration policy then. As things stand now, it seems unlikely the NZF vote share this year will exceed that in 1996.

LikeLiked by 2 people

What I am surprised is the pandering of white natives to the NZFirst party which is pretty much a Maori led party with most of its key members predominantly Maori. Voters now have a choice of a National government coalition with the Maori party or a National coalition with NZFirst another pretend to be white Maori party or a Green Party also stacked with Maori. White natives have abandoned the white native parties like Peter Dunnes United party and David Seymours ACT party.

LikeLike

Labour is not much better pandering to Willie Jackson and the 7 guaranteed Maori seats. The Maori King has moved his support to the Maori party. Smart man. He is basically telling the 7 Maori seats to vote with the Maori Party. This in effect gives Maori effective control of the National government with the likely support from Paula Bennet also Maori that pretends to be white and inconspicuous.

LikeLike

Am I am imagining it or have there been suspiciously few concrete proposals to address the underlying macro imbalances. I don’t mean pie in the sky stuff, only proposals that are consistent with modern economics. This blog has offered one such set of prescriptions; has anyone else?

LikeLike

Sorry but I think this doesn’t sound right, or feel right, or for that matter have any basis in reality,

“real GDP per hour worked is now about 37 per cent below the average for the countries in the upper half of the OECD ”

My reality antenna are twitching, I think you need to look at the measure used. firstly nominal GDP I suspect is measured differently, secondly what is real GDP and how is it measured, I suspect the “real” part of this equation is out, thirdly you need to look at hours worked and that definition, which I suspect is measured differently. They could be inflating the denominator real hours worked by mis-measurement or mis-defintion, as there is a lot of part time workers in NZ, perhaps they are being aggregated wrongly.

I reckon you go back 30 years you will find the error.

We are not 37% below the OECD average especially when you look at some of the cot cases that make up the OECD.

If it looks like a duck, quacks like a duck, then it is a duck, or official bullshit.

You could well be basing your arguments, especially immigration which is your default goto catchall for our supposed pitiful economic performance on a falsity?

LikeLike

I’m not sure why you think the broad sense of the numbers doesn’t ring true. There is a variety of ways of estimating those gaps, none perfect by any means, but I didn’t think anyone really doubted we were once among the wealthier and most productive countries in the world, and now aren’t. In this particular post, I just used the OECD’s own basis for comparison (population-weighted estimates of real GDP per capita of the upper half of the OECD, done using 2010 PPPs). Thus, to stress (a) we are not 37% below the OECD average, but below this measure of the richer half of the OECD, and (b) this isn’t a measure of real GDP per capita, where the gaps are smaller because NZers work longer hours per capita than people in most of the rest of the OECD (and esp than people in the richer half of the OECD).

Relative to Australia, until the late 60s/early 70s there was no consistent flow one way or the other across the Tasman – flows just reflected short-term cyclical differences. In the last 40 years, the overall flow has been heavily skewed in the\ direction of people leaving here for Australia. that suggests something real has changed and that perceived opportunities (largely probably reflected in productivity) have become materially better there than here. In the 2025 Taskforce’s report, that gap was around 35 per cent.

One should always be a little sceptical of particularly interesting statistics – they may well be wrong. In this area, I’m always a bit uneasy about PPP-based comparisons, even tho one has to use them to do levels comparisons. But one other comparison relevant in this area – and less reliant on strong assumptions – is growth in real GDP per hour worked, expressed in national currency terms. For that measure, the OECD has date for 23 members going back to at least 1970. Over the 45 years to 2015, only Switzerland had very slightly slower productivity growth than NZ – and even in 1970, on most measures, they were already richer/more productive than we were.

My immigration/location/real interest and exchange rate story might be wrong, or a much smaller part of the story than I reckon, but the evidence for our actual underperformance (whatever the cause) is pretty strong.

LikeLike

Something real happened. We stopped making things. I was with Fletcher when Fletcher dominated and was NZ’s largest company with huge manufacturing making things. It is now just a pale shadow in the construction sector.

LikeLike

I’ve been following this blog for about a month and in that period I don’t think Michael Reddell has suggested immigration is holding back NZ productivity; he is just saying there is no case for the supposed benefits that most politicians and the media claim.

I do not have the background to understand productivity figures; when I grew up it was fairly clear that most employees (men) worked in factories 40 hours per week and made things that were sold.The world is different now. There are service industries that are hard to measure (to quote GBS a more productive surgeon will cut off two legs rather than one). And for example supermarkets employ people to work 7 days a week covering long trading days. If we went back to opening just five days and from 9am to 6pm wouldn’t productivity dramatically increase at the expense of convenience to the public. Then there are self-employed workers who may wish to exaggerate the hours they work for various reasons.

So I do not really grasp the productivity data that makes up much of the arguments in this blog but I tend to trust the experts and especially bodies like the OECD who will be applying the same measures in multiple countries.

What I can understand are low wages. I have some knowledge of the UK, France and NZ and it seems rather obvious the NZ has low wages. For example looking at housing costs compared with the UK and it does seem our problem may be low wages not high prices. My belief is that immigration as currently practiced in NZ is holding down wages for the poor. That is the main reason I follow this blog. I will just keep reading until I understand productivity or I find I am wrong about the growth of modern slavery in NZ..

LikeLike

Bob

I do argue that our large-scale non-citizen immigration programme is holding back productivity growth in NZ (and, in consequence, holding back real wages).

(And, yes, productivity isn’t everything. As you suggest, if we went back to our pre 1980 shopping hours, labour productivity of shop workers might well be a bit higher, but it would be a lot less convenient for most of the rest of us. Like GDP, productivity is a proxy for things that are generally, but not always, well-being enhancing.)

LikeLike