I was participating in a debate the other day with a prominent economist and a leading business person. Both seemed keen on actively growing New Zealand’s population further – the economist in particular calling for a “population policy”, and appearing to argue that a much larger population was a critical element in improving New Zealand’s productivity outcomes. The principal channel that he appeared to have in mind was better physical infrastructure, notably (because he explicitly mentioned them) high speed trains between our major cities. Both my interlocutors seemed keen on a much larger population for Auckland – to which my response was along the lines of “what, and dig an even deeper hole than we’ve already dug”, given the economic underperformance of Auckland relative to the rest of the country over the last 15 years. None of this advocacy for an active policy role in growing population further appeared to give any recognition at all to

- the economic underperformance of Auckland

- the lack of any evidence that countries with smaller populations tend to be smaller or less productive than those with larger populations, and

- the lack of any evidence that small countries have been achieving less productivity growth than large ones.

As far as I can see, the only OECD country where there might – just might – be a strong case for an active government role in trying to grow the population is Israel, surrounded by much more populous hostile states. And even then, Israel’s survival so far – I remain a little sceptical that it will last longer than the Crusader states of earlier centuries – is more down to technology, organisation, institutions, and embedded human capital than to numbers of people.

But what prompted this post was a comment from the economist that not only should Auckland’s population be markedly further increased – and the residents urged into apartments – but that governments should be actively aiming to increase the population of our other cities and regions. The specific aspiration that caught my attention was the suggestion that our second biggest city – at present, Wellington and Christchurch have similar populations – should have a population around half that of Auckland. I was somewhat taken aback and responded “but that isn’t typically how things are in other countries”, to which the confident response was “oh yes it is”. So I thought I had better check the data.

I set aside very large countries, and extremely small ones. Most of Malta, for example, is Valetta. Even among the large countries there is quite a range of experience: Britain, France and Japan have single dominant city, while Germany, Italy, and the United States don’t. But I found 22 advanced (OECD or EU) countries each with a total national population of between 1.3 million (Estonia) and 17 million (Netherlands), and I dug out the data, as best I could, for the populations of the largest and second largest urban areas in each of those 22 countries. 20 of the 22 countries are in Europe, and Israel and New Zealand are also in the sample.

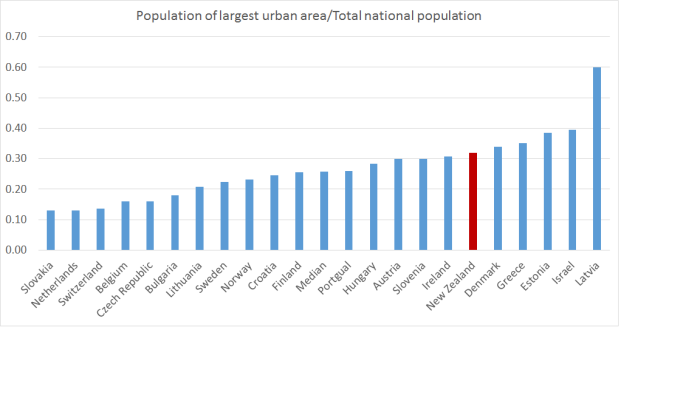

Here is the share of the total national population accounted for by the largest city in each country.

Among these smaller advanced countries, our largest city’s share of total population is a bit above the median, but nowhere near the highest share. Of course, as I have noted previously, except for Israel (Tel Aviv), our largest city has grown faster than any of these countries’ largest cities in the post-war decades.

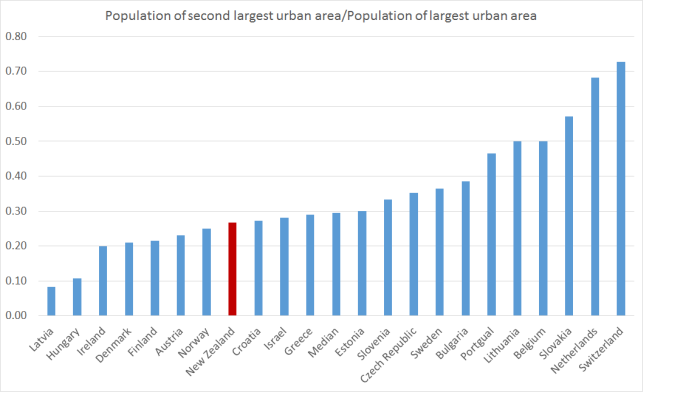

But what about the specific point at issue: the size of the second largest city relative to the largest city. Here is that chart.

There is huge range of experiences even among this group of relatively small advanced countries – from Latvia and Hungary where the second city is tiny relative to the largest, to the Netherlands and Switzerland at the other end. In those two countries, the largest city is quite small relative to the total population. There isn’t an obvious correlation between economic success and the relative size of the second largest city. Ireland and Denmark are much richer than New Zealand, but so are the Netherlands and Switzerland. And Latvia, Hungary, Slovakia, Portugal and Bulgaria are poorer than us. New Zealand’s number isn’t much different from the median country’s experience.

One thing worth bearing in mind in this sample is that in most of these countries, the largest country is also the capital. That isn’t so in New Zealand, Israel, or Switzerland – or, for practical purposes, the Netherlands. All else equal, one might hypothesise that Wellington would be smaller if it were not the capital – but that might just have left Christchurch as the clear-cut second largest city.

Since there is a wide range of experiences across similarly wealthy countries in the relative size of largest (and second largest) cities, it might be wise to be rather cautious in concluding that government policy should be actively directed to altering the relative size of some or other groups of cities. Patterns across countries are likely to reflect some mix of history, geography, and economic opportunities. In some countries, outward-oriented economic activity is heavily concentrated in big cities (one might think of London), in others it derives largely from non-urban natural resources (one might think of Norway).

As it happens, as a matter of prediction rather than prescription, I do think that a successful reorientation of policy in New Zealand would increase the relative size of second and third tier cities relative to Auckland. But it would do so because (a) Auckland’s population would no longer be supercharged by an aggressive immigration policy, and (b) because, as a result, overall population growth would be lower, there would be less pressure on real interest rates and the real exchange rate, and the outward-oriented economic opportunities, which are at the heart of the provincial economies, would be more attractive, and would see more business investment taking place.

If, instead, governments persist with large non-citizen immigration programmes then, for all the talk of the attractive lifestyle the regions offer, it is a recipe for even more of the same. Why wouldn’t that happen – doing the same thing again and again and expecting a different result doesn’t, to put in mildly, make much sense. For the last few decades, Auckland’s population has grown rapidly relative to that of most of the rest of country. And its relative economic performance appears to have languished – there is certainly lots of activity to keep up (more or less) with the needs of a growing population, but little productivity growth. Indeed, the large productivity margin one might normally expect to see in the data for largest cities is quite small in Auckland, and has been shrinking further. There is no sign of some critical tipping point being reached in which – say – high speed trains are about to transform our economic prospects.

As for the regions, one hears enthusiastic talk from time to time of encouraging migrants to the provinces – and last year the rules were further tweaked in that direction. But that is simply a recipe for further undermining the quality of the migration programme – less able people who are desperate to get in will go to the provinces, to pick up the additional points on offer. We want people to move to Invercargill or Napier – if they do – because the business opportunites there are sufficiently good to attract people, not because the government puts points “subsidies” on offer, which simply mask the serious structural imbalances in the economy. The best path to better provincial performance – not an end in itself, but probably part of a more successful New Zealand – is likely to be the removal of the distortions and policy pressures that have given us such a persistently overvalued real exchange rate for so long. Using policy to simply bring in lots more people won’t do that – any more than it has for the last 25 years.

This discussion is a microcosm of the why, how and where we’ve got to in Auckland to date. Both the economist and businessman are living in a bubble (probably a character Villa in Parnell and Ponsonby) and both definitely won’t have to contend with living in squalid apartment conditions competing with knockdown cheap immigrants for their jobs into the future. Absolute zero consideration for the citizens that have to live in this scenario long after they’ve made their bonuses and profits and have passed on their wealth and estates to their children. What is it with New Zealand business and the fascination with rentier capitalism? Get creative and do something real and valuable instead of sucking the life force out of the economy.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Get rid of the tourists and you will get rid of the knockdown cheap migrants. These two come hand in hand.

LikeLike

How would you get rid of the tourists? I’m not sure I’d want to, altho an economically successful NZ might be a more expensive place to visit (over the long haul). No country gets rich on the back of tourism, but isn’t just part of modern life (we do, and they do it)?

LikeLike

You can’t have one without the other. Fact of life, get used to it. Tourism is a $14 billion industry and the target is $25 billion in the next few years. Tough luck. foreign tourists have foreign needs therefore expect Chefs, waiters, prostitutes, baggage handlers and cleaners to top the list of skilled migrants that NZ hospitality industry will demand more and more of.

Andrew Little is dreaming if he wants locals to be trained and be apprenticed as curry chefs, foreign language waiters and geisha prostitutes.

LikeLike

I’m sure the industry will “demand” them. A government with any serious regard for the interests of its own people would simply say no.

Which doesn’t mean there are not some speciality roles in which temporary foreign workers might not be appropriate.

LikeLike

In fairness to my two specific interlocutors, neither is an Akld resident and one has a successful export-oriented firm. Nonetheless, I think your more general point stands.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Michael… bit off topic for this post, but I would be interested in the recent discussion paper on productivity produced by the RB… work by Steenkamp… which suggests that the return on capital has been very poor, which has been a drag on productivity and could be a partial explanation for the productivity puzzle…

I guess in respect of cities… many cities globally have these sorts of issues, but there are large agglomeration effects that accrue within cities…

The puzzle continues…

LikeLike

Yes, I haven’t got past the summary of Daan’s paper yet, but will try to write something about it next week.

Re agglomeration, I guess the thing about Auckland is that the agglomeration effects seem (on average) to have been so small. Arguably what comes of pushing more people into a place, beyond the “natural” capacity of the location to support suich gains.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The problem with the common assumption of agglomeration effects, linked to size and form of cities, is that all the studies being relied on, actually fail to prove causation, mistakenly relying on correlation in what are limited data sets anyway.

The study that SHOULD be getting the most recognition, is West, Bettencourt et al, which look at a truly representative large data set of cities.

http://www.newgeography.com/content/002987-density-not-issue-the-urban-scaling-research

It does seem fair to claim increased outright city population correlating with higher productivity on average. However, I think your intuition is correct, Michael, that there are circumstances now prevailing in many developed-nation cities, that significantly undermine the capture of agglomeration efficiencies.

In fact as the New Geography article points out, many advocates are leaping to the assumption that higher density, period, is associated with higher productivity, and this is completely wrong. This assumption has rested, in the past, on analyses of data sets of cities where the dense and productive ones largely evolved this way. It is absurd to think that this evolution can be magically replicated simply by planning a more compact city footprint by way of growth boundaries and upzoning. For example, Manhattan obviously evolved like it did without any compact-city planning ideology, but because global finance clustering fortuitously happened there.

In the case of the UK, whose cities have all been arbitrarily constrained in their horizontal growth and forced to be higher density, for decades, the result is REDUCED productivity, not increased! Several papers from Cheshire and colleagues at the LSE, and several by Alan W. Evans and colleagues, cover this effect. In fact most agglomeration effects in most cities most of the time, were helped to evolve by reason of availability and affordability of land. Land being hundreds of times more expensive per square foot, and almost all already built-out, is a powerfully anti-competitive effect.

The USA is an instructive counter-example in this modern era, in that it is possibly the only nation that still has some proportion of its cities unconstrained in their dispersion, and hence still forming clusters in the same way that most cities once did. California no longer has low-cost exurban land available, due to regulatory overkill, but that very famous cluster, Silicon Valley, evolved in the first case on low-cost exurban land. What is most instructive about the USA is that growth and the associated clustering that is FOREGONE in the cities succumbing to regulatory overkill, merely shifts to those cities that are still freely dispersing, where there is space and low land costs.

Auckland might well appear to be “fast growing” compared to data sets of cities that share the modern planning fads that tend to deflect growth to elsewhere – and the largest cities in any given nations are the most prone to these fads – but it does not match the fastest-growing cities in the developed world today, which are all middle-tier and small cities in the USA without “planning” chokes on dispersion, which are capturing the growth foregone elsewhere in the USA. Auckland is most certainly not growing as fast as Houston, Dallas, Atlanta, Austin, Raleigh, and Charlotte; and possibly Nashville, Indianapolis, Kansas City and several others are ahead too. These cities are growing fast BECAUSE they are staying affordable, simply getting on and building whole new edge cities and financing the infrastructure for growth, properly.

I believe that in time, the economics profession will be unable to evade the realities of agglomeration, growth, opportunity and inclusion, which CAN and do co-exist. The cargo-cultist planning-driven approach is doomed to failure other than the provision of a few exclusionary cities with lucky economic back-histories; these fail anyway on the opportunity and inclusion factors – and all other cities that are not so lucky, will fail on everything.

NZ is making a massive mistake by default, pursuing the failed UK model where ALL cities are in planning straitjackets and there is nowhere for real honest growth to be deflected to. Auckland shares with several other “success story” cities (according to the planners), including NYC, London, and Vancouver, the dirty little secret that much of the “intensification” is actually overcrowding among immigrants (who were used to these living conditions in their country of origin) and the poorer incumbent locals (the following generations of whom will be completely priced out).

LikeLike

I think you have the wrong end of the stick as usual because it is actually industry the drives the type and the numbers of immigrants, permanent and temporary to get the jobs done. Government cannot change targets willy nilly because industry will at the end of the day prevail over time will force a minimum target. The 50k target has stood forever which does usually mean that it is the minimum time tested target. The recent 5k that National was under pressure to change downwards as a poll saving gesture will just put a lot of businesses under real pressure and I know a few restaurants that have closed because they were unable to replace their chefs. And clearly hoteliers are screaming for skilled chefs. Real businesses that need labour to get their businesses growing.

Therefore you cannot look at the migration targets and decide it is wrong because it is fundamentally a derived target time tested and not a dreamt up target.

If we want higher productivity then we have to change the type of industry focus from low skilled and low productivity enterprises to high skilled and high productivity type industry. Our top 4 industries, Tourism, Milk, Meat and International Students all require an army of low skilled labour and that will not change the productivity dynamics. It is about time you face reality and recognise that industry drives the type of migrants and not the government. So change comes from changing the type of industry focus and not to change the type of skilled migrants or even to stop migrants all together because our Tourist, meat, milk and student industry are already screaming for labour and its all low skilled, chefs, waiters, cleaners, hearders, butchers, baggage handlers, prostitutes and more cleaners and more cleaners.

LikeLike

But ‘who’ sets the direction of industry? I would say largely business people and per World Bank rankings, in NZ, this is a relatively free choice. After all, NZ is a magic destination which visitors are prepared to pay to experience so companies are established to meet the demand and while these enterprises may be staff heavy, they are typically capital light. Which is all rational: an entrepreneur eyes a return on capital – not aggregate productivity statistics. Better for the government to focus on education, education, and education…….

LikeLiked by 1 person

Education by itself does not create jobs if there are no highly skilled jobs in NZ we will continue to see mass exodus of young kiwis. That is why young highly trained kiwis depart overseas for better jobs and better pay in countries that provide those highly skilled jobs.

LikeLike

Don’t we have a problem with unemployment among the unskilled among the domestic population?

LikeLike

Hospitality New Zealand(HNZ) general manager of operations and advocacy Tracy Scott said with the growth in tourism, vacancies were increasingly filled by temporary migrant workers.

“Sometimes it comes down to Kiwis just not wanting to do that kind of work. It’s hard work with odd hours and it suits people who are passing through on holiday.”

Federated Farmers dairy chair Andrew Hoggard said he would be concerned if the supply of migrant workers was cut back. In low unemployment areas like Southland, it was hard to recruit Kiwis.

Turbo Staff recruits for the construction industry and managing director Ihaka Rongonui said he had about 130 Filipinos on his books in Christchurch and they made up more than half his placements.

http://www.stuff.co.nz/business/80812202/key-industries-would-struggle-without-migrant-labour

LikeLike

People tend to become more willing to do such jobs when the pay rate is higher. If fewer immigrant workers were available, wage rates in those sectors would tend to raise and, on the other hand, interest and real exchange rates would be lower.

LikeLike

I’d say there’s more economic upside in Auckland becoming a widely admired medium sized city – like say Kyoto, Barcelona or Vienna – than a large generic city.

LikeLike

Largely agree, altho I suspect Akld was mostly be a gateway rather than a destination. And Vienna’s population is still almost 50% larger than Akld’s.

LikeLike

I keep trying to point out that it is absurd for planners and politicians to postulate Hong Kong as the model for far too many cities including Auckland. Auckland needs to just run with its existing identity and be proud of it, like Nashville and Indianapolis have instantly recognisable identities, even worldwide. The kind of immigrants we want, should be the ones that want to share in our traditional way of life – Indy and Nashville get plenty of immigrants – not ones that will participate in turning Auckland into another borg-cube rentiers paradise.

LikeLike

The overall residence target is certainly “time-tested” – has been in place for 15 years or so (and was essentially a number plucked out of the air when it was devised), and in that time there has been no sign of an acceleration in productivity growth. Many of the details have been subject to quite frequent change, including the wave of new working holiday schemes, the ability for students to work while here etc etc.

Our actual inflows are a mix of business and govt-determined. At the limit, the govt could clearly stop any non-citizens coming, or it could adopt an open borders policy. Actual policy is nothing like either extreme.

I agree it would probably be unwise to make sudden non-foreshadowed changes of policy. But to give indsutry and indviduals say a year’s notice of a progressive reduction in the residence approvals target, and a progressive tightening in the work visa rules (so that, say, over 5 years we get to the point where, generally, no one earning under $100000 pa is generally able to get a work visa) would be entirely reasonable and would, in my view, lead to improvements in NZ productivity and overall economic performance, and increases in real wages for NZers.

LikeLike

As long as industry is service driven then it is low productivity. I went into a top chinese restaurant in Melbourne recently and there was a separate waiter for each dish presented and a chef accompanying each dish presented. There were more waiters and chefs hanging around than there were clients, expensive but well worth the visit just to see the number of service personnel pampering your every need.

LikeLike

Sure works out for cleaners to be able to get a wage of $100,000 a year. But not sure if it works out for businesses if we have to pay cleaners $100,000 a year.

My young IT aspiring nephew with a honors degree just got his wings in Computer science is just weighing up his options as a lawn mowing gardener because I am paying $40 for a half an hour job to mow my lawns which meant that moving lawns was paying more than an IT graduate in Auckland.

How is that helpful if low skilled labour is paying more than high skilled kiwi labour even in the current environment where the person currently mowing my lawns is a migrant from India for $40 an hour? Oh yah thats because he bought the lawn mowing business off a kiwi bloke and i felt discriminatory against him if i dropped the charge out rate.

LikeLike

My son with double degree from Monash, one honours, and 20 years high level experience in Australia including 8 years with IBM Australia has been embroiled in the recent extreme outsourcing of IT to India. Last year IBM laid of 5000 staff and replaced them with IT staff from India at $10 per hour

Mowing lawns is looking good

LikeLiked by 1 person

A high-performing economy eventually drives out low-paying (= low labour productivity) jobs, shifting the overall mix of sectors in the economy, and encouraging the adoption of technology as it becomes feasible/economic. The typical farmer milks many more cows than 100 years ago, assisted by the rise of technology. Telephone operator jobs largely don’t exist any more.

By contrast, when I lived in Zambia many of my expat neighbours routinely had perhaps half a dozen servants (maids, gardeners, cooks, child-minders).

LikeLike

Sure, you may need fewer people to milk more cows but this is where your productivity equation falls over because in the past you did not have to worry about the waste of a small herd of cows. But now we are dealing with 10 million cows which need to be looked after, deticked with tons and tons of chemical wash, cleaners need to clean up the machinery, electricians to service the machinery, the waste water treatment, the leaching into waterways, the dirty waterways, the contaminated drinking water, the methane gas pollution in the atmosphere, the ozone layer depletion, the deforestation and maintainance of feeding grasslands that once was a mighty kauri forest.

The industry at $10 billion is already creating a havoc on the natural environment. There is nothing natural about exporting 99% of milk production. In other words, our local population do not drink all that milk that is being produced but the industry extracts a very heavy subsidy and the people pay a very high price environmentally.

LikeLike

Your productivity equation is totally up the creek when 10 million cows generate a export GDP of only $10 billion but 4.5 million people generate $160 billion in net disposable income.How can cows ever match humans for productivity. Only economists can dream up such nonsense.

LikeLike

The late Sir Paul Callaghan was a non-economist whose insights on this subject showed up the economists. Watch one of his presentations, “Beyond the Farm and Theme Park”.

LikeLike

Reading between the lines together with you comment about “points subsidies” driving less gifted, or less able. or more desperate migrants, to the regions, it stands out that the 3 places with international airports are going gang-busters, while Wellington is languishing in the size stakes could well benefit if the lever pullers could extract themselves from the Wellington airport expansion imbroglio and simply get on with providing Wellington and thus the lower North Island with a competing gateway (competition for Auckland) – would go towards producing some rebalancing you skirt around – declaration – I’m not a Wellingtonian and have never lived there

LikeLike

Does a nation of 5 million people need several international airports? The USA works on gateways, hubs and spokes, after all.

Certainly our largest airport, Auckland, suffers from an unlikelihood that it will ever be as efficient a gateway / hub as the famous US ones.

NZ needs a far-sighted program of “new cities”, not planned to death like Brasilia or Canberra, but being pragmatic about what the country needs, and the practicality of the do-ability somewhere that land is low-cost, infrastructure is low-cost due to terrain, and NIMBYism is absent. Low-cost market-led growth in housing and business premises along the model of the USA’s noted examples, should be a central element. All existing airports should become “spokes”, and a real international one built somewhere else as a kick-starter of a new “opportunity urbanism” city.

The correct role for planners in such a city, is described by Bertaud, Angel, Romer and colleagues in various works including videoed presentations. Stick in rights-of-way for future trunk infrastructure to ensure that it can be done at low cost once needed. 100 years + ahead of the actual growth. It costs almost nothing to do this, and costs a LOT later on if you have NOT done it. I understand there is exactly 3 kms of “designated corridor” protected in NZ right now. DUH! DUH! DUH!

LikeLike