Fidel Castro is dead. Sadly, the same can’t be said for the brutal regime that has controlled Cuba for 57 years now – the regime that suppresses speech, religion, and the exercise of democratic freedoms that we take for granted; the regime that executed thousands of its political opponents and which, to this day, imprisons many of those brave enough to stand against it; the regime that suppresses free economic activity; the regime that actively tries to stop its own people leaving. There have been plenty of awful Latin American regimes in the last 100 years or so, but fortunately most of the worst have now passed into history. But not the Cuban regime. I won’t rejoice in anyone’s death, but consider what type of man this was: Fidel Castro had enthused about the idea of a nuclear attack on the United States, and had to be put in his place, in no uncertain terms, by Khrushchev.

Last week I happened to be reading Stephen Ambrose’s history of the Eisenhower presidency – the last non-politician to become President of the United States. Never having read that much about Cuba, I was surprised to learn that US government agencies – and this at the height of the Cold War – were genuinely uncertain what to make of Castro at first, were reluctant to conclude that he was a communist, and (in parts of the government at least) were initially reluctant to see him toppled, for fear that others, notably his brother (the current President of Cuba) would be worse.

But this blog is mostly about things economic. I knew that pre-Castro Cuba had been a reasonably prosperous place by Latin American standards. The southern countries (Chile, Argentina and Uruguay) were richer, and so was oil-abundant Venezuela. But Cuba in the 1950s is estimated to have had real GDP per capita higher than, for example, that in Bolivia, Brazil, Paraguay, Honduras, El Salvador and Ecuador. Most Cubans – including Castro – were descendants of Spanish migrants, and in the mid to late 1950s, real GDP per capita in Cuba is estimated to have been around 75 per cent of that in Spain.

What has happened since then? Like all countries, Cuba has had its relatively good and relatively bad periods – the latter, notably, after the fall of the Soviet Union. And data sources for such a controlled economy aren’t that abundant, or probably that reliable. However, Angus Maddison’s international database does have real GDP per capita estimates (all on a PPP basis) for Cuba from 1929 through to 2008 (the successor Conference Board database doesn’t include Cuba).

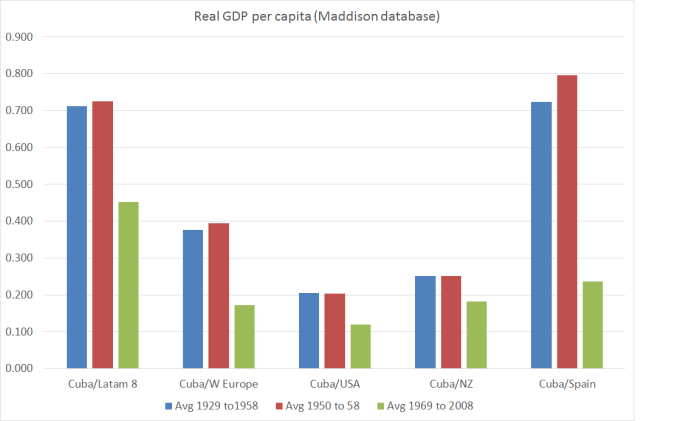

Here are estimates comparing real GDP per capita estimates for Cuba with those for other various other countries/groupings. Here I’ve shown averages for (a) the thirty years prior to the Castro takeover, (b) the 1950s immediately prior to the takover, and (c) the forty years from 1968 to 2008. And I’ve shown comparisons between Cuba and the United States, Spain, and New Zealand and also those with Maddison’s Western Europe measure and his measure for the eight largest Latin American countries for which there is annual data all the way back to 1929. Using these averages masks the shorter-term volatility, but in looking at the Castro period the picture wouldn’t be much different if, say, I’d used just the 2008 observation rather than the 40 year average. The big decline in Cuba’s economic fortunes took place in the 10 years after Castro’s revolution.

Against all these countries/groupings, Cuba’s performance in the Castro period has been worse than it was previously – dramatically so when compared to the Latin American grouping, Western Europe, or to Spain, the former colonial power.

Having said that, I was a little surprised that the deterioration had not been even more marked. If the numbers are roughly reliable – and that is a significant caveat – then in 2008, Cuba’s real GDP per capita was still higher than those in El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Paraguay.

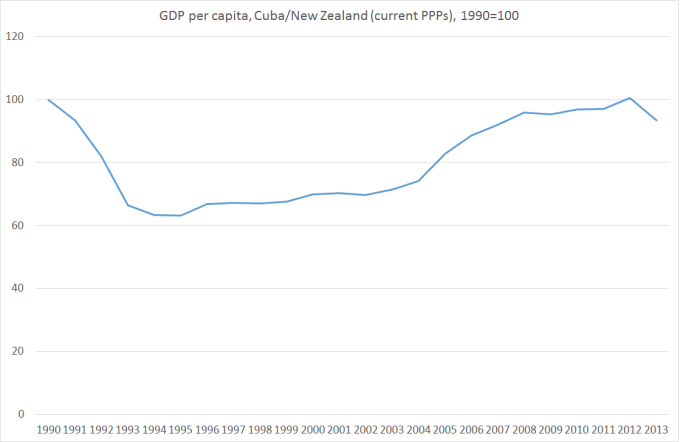

Looking around for something a little more up-to-date, I found the World Bank had data showing PPP-adjusted current price per capita GDP estimates for the period 1990 to the present. In Cuba’s case, “the present” only being up to 2013.

This is how Cuba has done relative to New Zealand over that period. I’ve just set both countries’ GDP per capita equal to 100 in 1990 and so shown the relative growth since then.

It is a little depressing. 1990 was just before the collapse of the Soviet Union, and you see the subsequent sharp fall in Cuba’s performance in the early 1990s. But over the entire 23 years, on this measure, there has been no change in New Zealand’s performance relative to that of Cuba.

(Here is a link to a post that puts Cuba’s economic performance in a rather more gloomy overall light. I think it is a little unfair to compare any country’s performance to world GDP over recent decades, given that China is a significant chunk of the world and China had – and has – so much ground it had to make up after the self-destruction over much of the 20th century.)

Of course, one of the other salient features of Cuba’s experience since Castro took power was the emigration to the United States. Cuba’s population in 1958 was around 6.8 million. Current estimates are that the Cuban-American population is around 1.2 million. That outflow – which would, presumably have been much larger if the Cuban government had not put tight exit controls in place – was large enough that Cuba’s population growth in the 50 years after the revolution was the second lowest of all the Latin American countries Maddison reports data for (only Uruguay – with its own large scale emigration- had a lower rate of population growth in that period).

New Zealand is, of course, another country that has experienced a large scale net emigration of our own citizens. Since 1958, it is estimated that 975000 New Zealand citizens (net) have left New Zealand permanently (and in 1958 our population was only 2.3 million).

I don’t want to make much of the Cuba/New Zealand comparisons. They can be crass, and risk trivialising the appalling oppression, persecution, and suffering of the people of Cuba, many of whom had – and have – no way of escape. And I’m not sure I believe the Cuban GDP numbers anyway – and I see Tyler Cowen also highlights that issue.

But, equally, it is too easy to come to simply take for granted the massive outflows of our own people over recent decades, and the disappointingly poor relative economic performance. Freedom is a great blessing, as is democratic choice (and legitimate exit options likewise), but our democracy – and decades of chosen leaders – has kept on failing our people. We really should have been able to do a great deal better.

UPDATE: Various people have commented on the possible achievements of the Castro regime, especially in literacy and health. Tyler Cowen had a link to this post, which I found useful in making sense of the merits of the case in that area.

Have you seen the Quarz stat summary of Cuba?

http://qz.com/846313/fidel-castro-cuba-under-castro-by-the-numbers/

Still, I would have preferred to live in Cuba rather than any of the other Central American countries (apart, perhaps, from Costa Rica).

LikeLike

Michael, thanks for the excellent analysis. I had been thinking the same thing myself about the exodus from two small island nations to their much bigger, more prosperous neighbours. I also wondered how our literacy rates compared, given that increasing literacy was one of the triumphs of the Cuban revolution and we seem to have an awfully high number of New Zealand’s young leaving school with very poor reading/writing ability.

LikeLike

Thanks Graham. Not sure how comparably the literacy rates are measured, but at least within the OECD area (common methodolgy) the recent study suggested NZ adults had the fourth highest literacy rate.

http://www.education.govt.nz/news/new-zealand-fourth-in-oecd-for-adult-literacy/

LikeLike

Thanks. I’d have taken most of the others over Cuba (exceptions perhaps Nicaragua, Guatemala and one or two others) for two quite different reasons: first, freedom of religion is hugely important to me, and Cuba was/is much more restrictive there, and second, the abuses in most of the other countries are now mostly a thing of the past. Chile, for example, was pretty awful in different ways from say 1970 to 1990. Cuba has has 57 years and counting…

LikeLike

Michael, thanks for the analysis, your posts are always very interesting reading.

Do you have any ideas, recipes or even a plan on how the underperforming NZ economy can be fixed?

LikeLike

Probably the largest single component of my prescription would be a sharp sustained cutback in our non-citizen immigration policy, which is very ill-suited to a country so remote and so natural-resource dependent. But I outlined in this post https://croakingcassandra.com/2016/06/24/17690/ a variety of other measures I would support, and some of the reasons why they, without the immigration policy change I propose (cutting the target inflows non NZers from around 45000 pa, to around 10-15K per annum) wouldn’t be enough. As that post notes, I really got thinking hard about this issues when I was involved in the 2025 Taskforce’s work in 2009 and 2010. I supported most of what they proposed, but it just didn’t seem enough, or sufficiently focused on the specifics of the NZ situation.

LikeLike

GDP/capital does not measure everything of value. What about life expectancy, education levels compared with other Latin American countries over that time period. Also need to factor in the US economic blockade.

LikeLike

Entirely agree with your first sentence, altho it is typically a fairly good indicator of whatever good stuff societies can afford. Re the US blockade, yes, altho on the other hand one also needs to factor into Soviet preferential purchasdes/subsidies in the earlier decades, and Venezuelan cheap oil more recently.

I’m not sure how the social indicators will have compared over time with those of other Latam countries, but did notice a piece this morning noting (from a contemporary ILO report I think) that in the late 50s, pre-Castro, Cuba already had one of the lowest infant mortality rates in the world, It isn’t terrible now, but the ranking is less good than it was then.

Literacy is an interesting one. Even if Cuba had 100% adult literacy, would one prefer that – and all the restrictions on what one can read or write – than say a 95% literacy rate and freedom? If there really were such a choice – which there needn’t be – different people might choose differently. I’d probably favour freedom.

LikeLike

Michael Reddell and freedom

Once upon a time .. a school teacher told us this story .. 80% of the people are like sheep, preferring a paddock with a fence around it so they know what they can, and cannot do. What the rules are. They dislike freedom. They need someone to set the rules. The other 20% cannot stand confinement. They need open space, the freedom to move, the freedom to think, and the freedom to act. They are decision makers. Remove the fence from around the 80% and they become lost. Place a fence around the 20% and they become lost

LikeLike

Every society needs rules, formal and informal (“how are things done here”). The question is which freedoms. Anglo societies have mostly flourished, and been some of the richest and most peaceable countries in the world in the last few hundred years with freedom of speech, freedom to toss out the rulers, freedom of religion, and respect for private property rights. Never absolute of course, not perfect, but typically better than the alternatives.

LikeLike

OK, now that’s out of the way let’s get on to the Productivity Commission report!

LikeLike

Coming…but probably not until Wednesday. It is a serious contribution to a discussion/debate that needs to be had, and I want to engage with it on that basis.

LikeLike

Speaking of Cuba and freedom, it’s hard to imagine without visiting exactly how pervasive the fear of authorities is there and how it plays out in their everyday life. I was shocked to see a Cuban friend in the privacy of her own home being too scared (like many Cubans) to mention Fidel’s name in case she was overheard through the paper-thin walls of her apartment and someone identified her as being critical of their Dear Leader. Instead, she stroked an imaginary beard to identify who she meant, which is a common pantomime. Another time I asked a woman who wanted to learn to speak English why she didn’t talk to foreigners in cafes in Havana. She snorted and said: “I’d be arrested as a prostitute.” Police are everywhere and feared.

LikeLike

Would be interesting to see if despite a drop in GDP, if the distribution of GDP was more equitable than prior to the Castro regime ie more individuals might actually have felt better off and a small number much worse off?

LikeLike

interesting possibility. of course, many of the “rich” got out in 1958/59.

LikeLike

Well Mr key seems to have treasury and productivity sorted in his opinion.

He was clear that Treasury don’t know anything and their forecasting is rubbish (in fact I agree), about as accurate as the RBNZ and he seems to consider that the question of productivity per capita is not worth bothering over.

.PM says Treasury’s forecasts of blow-out in debt by 2060 without NZ Superannuation changes “a load of nonsense”; says Treasury couldn’t get forecasts right 44 days before Budget ‘let alone 44 years out’; also downplays weak productivity

http://www.interest.co.nz/news/84800/pm-says-treasurys-forecasts-blow-out-debt-2060-without-nz-superannuation-changes-load

LikeLike

New lows reached by the PM. Quite sad really, and I suspect that in 2008 he never thought he’d be reduced to such a level of “analysis”. Must be quite embarrassing for his own policy/analytical staff.

LikeLike

Clearly economists are extremely poor at forecasting. Treasury and the RBNZ are usually out by a massive amount. It is time to bring senior and experienced Chartered Accountants into the Treasury.and into the RBNZ. Poor forecasting leads to poor decisions. If actual vary from forecasts you need to explain the variance. Economists have a bad habit of completely ignoring facts because it does not fit their static models. The PM is saying clearly to get out of your ivory towers and look at reality.

Poor productivity is driven by our white liquid gold, milking cows and tourists.

Farmers vote National Party so it is rather difficult for the PM to rubbish the 10 million cows that require an army off cleaners which is low skilled and low productivity. 10 million cows only generate a tiny $10 billion in export sales. Compare that with 4.5 million kiwis generate a net disposible income of $160 billion. If we counted the cows rural NZ would be highly unproductive compared to Auckland. One of the dirtiest commercial activities on the planet and economists in their supreme stupidity ignore the number of cows in their productivity calculations.

3.4 million tourists generate $11 billion but they also require an army of foreign chefs and foreign waiters and foreign prostitutes to service their foreign needs. Our low productivity in.this is that we provide fresh air and beautiful scenery which is free compared to the theme parks offered by the Goldcoast that extract billions for every theme park. Again our economists fail to recognise that free clean air and beautiful scenary is highly unproductive. Auckland international airport handles 17 million inbound and outbound passengers per annum. No wonder Aucklanders are considered unproductive. But statements from economists that Auckland is an anchor on NZ as a whole is just plain stupid.

LikeLike

We should also bear in mind that Michael’s graph does not account for the effects of the US embargo (people, goods and financial) imposed by JFK in 1960. For Cuba, the effects of that monstrous act were hugely significant.

In fact, Cuba estimated the cumulative cost of the embargo by 2013 to be US$1.126T. Of course, like their GDP figures, we should take their estimate with a generous dose of salts, but the fact remains that, with the embargo in mind, compared to New Zealand, Cuba’s relative performance seems pretty impressive.

All of which begs the question of just how badly served have we been by our financial overseers?

Or more cheekily: hey, how good can communism really be?

LikeLike

It also doesn’t take account of Soviet and then Venezuelan support. I’m not defending the embargo, but eastern European communist countries didn’t do that well even without embargoes.

LikeLike

I agree, but surely any rational analysis would find that Soviet and Venezuelan support, such as it was, would pale into insignificance compared to the effects of the embargo.

Humour aside, I’m completely agreeing with you that our economic performance has been abysmal, considering our endowments.

LikeLike

I’m not so sure about the blockade vs Soviet and Venezuelan support. After all, look at the collapse in Cuba’s GDP in the years immediately after 1990 when they could no longer sell sugar at far above world prices. The scale of the fall in GDP suggests the “subsidy” was pretty important. But it would be interesting to see a careful studying trying to evaluate the role of all three interventions.

LikeLike

I’m not defending Mr Castro but a counterfactual of 1950s status quo (Mr Batista et al.) would have ongoing US interference, assured GDP growth, dodgy human rights, and one third of the population living in poverty. Casting eyes around the world, such an environment breeds revolution. Luckily the US has learnt from such mistakes. Oh wait…

LikeLike

vs the actual situation of next-to-no human rights?! (recognising that you aren’t defending Castro)

and yes, I think US intervention abroad since WW2 (well, at least since Korea) has generally been counterproductive for the US and for the people in the countries intervened in

LikeLike