It is a trifle unsettling to check out the Geonet pages, notice the large cluster of continuing aftershocks around “25kms east of Seddon”, and then to realise that looking out my window I can more or less see that spot. It surprises me quite how much damage and disruption Wellington has already had despite being several hundred kilometres from Culverden and the site of Sunday night’s major quake.

US politics and a good book make worthwhile distractions.

I’ve just been reading The Broken Decade: Prosperity, Depression and Recovery in New Zealand 1928-39, by the local historian Malcolm McKinnon. It is, as far as I’m aware, the first substantial scholarly history of the depression years in New Zealand.

The Great Depression was a tough time for many people in many countries, New Zealand not excluded.

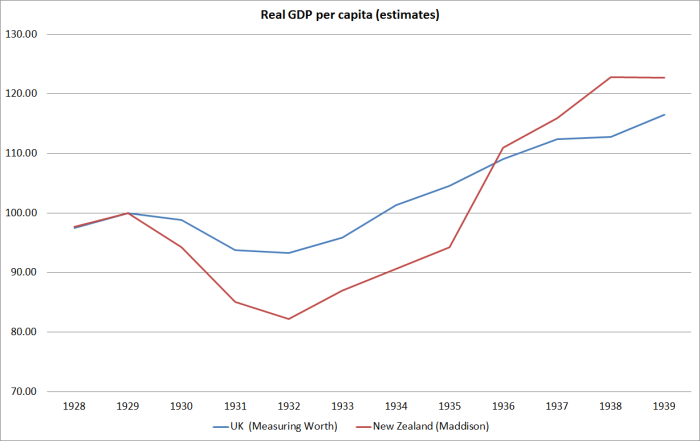

Whereas for the UK, the fall in real per capita GDP wasn’t much larger than the experience in the 2008/09 recession (and the 1930s recovery was faster), in New Zealand real GDP per capita is estimated to have fallen by almost 20 per cent.

No wonder there was a net migration outflow during the Depression – small, by the standards of some we’ve seen since, but then the travel costs back to the UK were much greater than today’s three hour flight to Sydney, Brisbane or Melbourne.

No wonder there was a net migration outflow during the Depression – small, by the standards of some we’ve seen since, but then the travel costs back to the UK were much greater than today’s three hour flight to Sydney, Brisbane or Melbourne.

What made it so tough for New Zealand? We went into the Depression with staggeringly high levels of debt – high government debt (perhaps around 170 per cent of GDP just before the Depression), and a highly negative net international investment position. Most of the external debt was owed by the government (central and local), and most government debt was external. And within New Zealand there was a huge level of farm debt – mostly not owed to banks (which didn’t do that sort of long-term finance) but to government agencies, non-banks, relatives, and to other individual private sector entities. Many farmers bought their farm, and the seller (whether family or other) left mortgage funding in the farm to be paid off over the subsequent decades.

When export prices, and consumer prices, fell very sharply, the debt overhangs became much more pronounced. In respect of the farm debt, wealth was reallocated among New Zealanders (lenders better off, borrowers worse off, at least if debt servicing was maintained). In respect of the public debt, the servicing burden became much more difficult, and a larger proportion of New Zealand’s nominal GDP has to be devoted to servicing that debt. Nominal GDP is estimated to have fallen by a third between 1929 and 1932 – and export receipts fell 40 per cent. The additional servicing burden was particularly severe on the foreign debt which still had to be serviced in sterling, as New Zealand’s own newly-emerging currency gradually depreciated against sterling.

The extent of the fall in activity in some cyclically-sensitive sectors was pretty stark: building permits issued for new houses and flats fell by almost 80 per cent.

But, no doubt as ever, it wasn’t all contraction and decline. Electrical appliances were becoming ever more widely adopted, and with it electricity generation continued to expand right through the Depression years.

Perhaps even more striking was dairy sector production and exports. Sheep numbers in 1935 were almost unchanged from the level in 1929, but the number of dairy cows in milk was 42 per cent higher than in 1929. And here is total dairy production.

I’m not sure I understand quite what was going on in that sector: presumably some combination of new technology, the desperation that came from the high levels of debt hanging over these farmers, and low direct marginal production costs (family labour) made it worthwhile to markedly increase cow numbers and overall milk production despite the low international prices for dairy products.

And substantial as the overall drop in real per capita income was, the fall was spread very unevenly across the population (as is no doubt the case in every recession). Unemployment was high – estimates vary, but even among adult males the unemployment rate probably peaked near 15 per cent (I’d give you 1991 comparisons if only the Statistics New Zealand website were not down in the earthquake aftermath). And there was a lot of resistance to wage cuts during the Depression, but for many of those who kept their jobs – and especially those in salaried jobs, not affected by cuts in overtime hours – real purchasing power actually increased during the Depression. My own grandfathers were in their mid-late 20s when the Depression began – both were in work throughout, and both bought new houses in the early 1930s. As McKinnon highlights, as much through his large selection of photos as from the text, “life went on”: society ladies graced race meetings, the All Blacks still played, and so on.

McKinnon’s book advertises itself as focused on the politics of the period, rather than the economics, and although there is a lot of economic-related material in the book, New Zealand is still lacking its first book-length economic history of the era (although of course it is treated to some extent in the few economic histories of New Zealand). Putting New Zealand’s experience systematically in cross-country comparative perspective (eg New Zealand, Australia, Canada, Ireland – and perhaps Uruguay and Argentina – and, say, the United States and the United Kingdom) would be fascinating.

It is a richly documented book, but with some gaps. For a book avowedly focused on the political side, it was surprising that the author had made use of New Zealand official archives, but not those of the UK – key export market, key source of finance in a stressed period, and of course key international relationship more generally. And even locally, although the book covers the whole period 1928 to 1939, there is very little attention to developments on the right of politics after 1935, including the formation of the National Party.

In terms of policy responses to the Great Depression, my own sense is that the politicians did about the best they could. With hindsight it was clear that a substantial currency deprecation would have been a helpful remedy – perhaps the single most potent response New Zealand could have deployed in the face of a severe global downturn. But in 1929 there still wasn’t a strong sense of New Zealand even having its own currency, let alone it being something that our government could control the value of. As time went on, the option of a more structured devaluation became a centrepiece of the policy debate – advocated by many economists – but even then the dividing lines weren’t clear cut. Export industries generally welcomed the idea, but workers and unions – focused on the expected rise in the cost of imports – didn’t. And for a government with a massive foreign debt, the additional servicing burden from a currency depreciation was a certainty, while the expected increase in tax revenue over time was no more than a hypothesis. When the government finally acted in early 1933 to formally depreciate the exchange rate, it prompted the then Minister of Finance, William Downie Stewart, one of ablest figures then in politics, to resign in protest. For several years afterwards, the devaluation remained a point of political contention (and even scholarly contention – at the time the US academic Kindleberger, later famous, argued that our devaluation had largely just pushed down the international price of dairy products).

Of course, the standard Keynesian line is that countries should have used fiscal policy more aggressively to attempt to maintain demand through the Depression years. Sadly, New Zealand was already debt constrained, and external debt markets were fragile at best. Additional public spending (even if totally domestically financed) might have boosted demand, but it would also have put more pressure on the balance of payments (in a non floating exchange rate world). A few years ago, in Paul Goldsmith’s book on the history of the New Zealand tax system, I stumbled on what should surely be the last word on the possibility of New Zealand borrowing and spending more back then, from Keynes himself.

Visiting London in late 1932 (after the worst of the disruption to the UK external capital markets was over), Minister of Finance Downie Stewart met Keynes. Stewart recorded in his diary:

“I asked him if he would borrow if he was in New Zealand in order to get through the crisis. He said, “Yes, certainly if I were you I would borrow if I could, but if you asked me as a lender I doubt whether I would lend to you.”

By that time, the fall in the price level had taken the level of government debt to well over 200 per cent of GDP.

The servicing burden of high levels of public debt was a major issue in many countries during the Depression. In some cases, it led to direct defaults: Germany, for example, simply ceased paying reparations (and New Zealand, as a small recipient, was a loser from that). The UK, and various other European countries, ended up defaulting on their war debts to the United States (the UK also suspended some of our war debts to them). In other cases – not just involving government to government debt – the approaches were more subtle, but they involved effective defaults nonetheless. In the United States, for example, government bonds had typically been payable in gold. The Roosevelt administration had those clauses revoked, and at much the same time went off gold, effectively depriving holders of a large proportion of their contracted returns.

In New Zealand (and Australia) there was a different approach again. In respect of domestic government bonds, holders were simply forced to accept a lower interest rate on existing debt than they had contracted for – as part of the legislation, if they didn’t accept the exchange, they would face a punitive tax to achieve the same effect. I wrote about that interesting episode in a Reserve Bank Bulletin article a few years ago.

What was interesting, in both countries, was the reluctance to do anything about the foreign debt (much the largest component of both countries’ public debts). The unexpected fall in the price level, and in nominal incomes, had massively increased the burden of the debt. But both countries still needed access to those funding markets, to rollover maturities at very least. Neither country defaulted on central government external debt, focusing instead on the goal (about which they could do nothing much directly) of raising the world price level, so as to lower the effective servicing burden. That finally happened, although in New Zealand’s case market unease about New Zealand’s external debt remained a serious concern – much more so than anything in the last 30 years – right down to the outbreak of the war. Had it not been for the war, external default might well have happened in 1939/40.

This has been a fairly discursive post. There are a lot of other aspect of the Depression in New Zealand I could write about – especially the handling of distressed farm debt – but I’ll save those for another day. For anyone interested in New Zealand’s experience of the Depression, I’d recommend McKinnon’s book. It is a sobering remind of an event that still shapes perceptions, and where – among the now very old – memories are still often seared by the experience. Never again, people hoped for decades. And then there was 21st century Greece.

I must read this book, it seems to back up my position that WW11 saved both Labour and NZ financially.

Something historians especially those wit a left lean have ignored til now.

Regarding the lift in cow numbers, both my grandfathers were sheep farmers, one of whom had a fair bit of debt having bought an additional farm in 1926, both milked cows during those years.

Mostly to get some cash flow and occupy sons who had to leave school early because of the lack of same.

Again the outbreak of war meant those same boys (who mostly volunteered for the airforce) got an education, foreign travel and a good start financially after the war.

If they survived!

Which they did but one of my mothers uncles lost three sons, so war is not the best answer.

LikeLiked by 1 person

On the 1939 situation, my interpretation is substantially drawn from the writing of Brian Easton, who is pretty left wing. I think the room for debate is about what the consequences of default might have been. NZ was still one of the very richest countries in the world, and one could argue that altho the debt was high, the problem was mostly a liquidity/confidence effect. A few years of austerity and I suspect we’d have been right again without too much long term damage.

LikeLike

Long-standing family friends survived the Depression much the same way on their Rangitikei hill country sheep farm: the (then) father and young adult son hand milked a herd of dairy cows very early every morning, and the son drove the full milk churns out of the hills to the closest Dairy Factory, near Taihape. No wonder he joined the Air Force on the outbreak of WWII – he probably viewed it as a rest therapy!

LikeLike

Let us not talk about the impact upon women.

LikeLike

My impression would be that mostly there wasn’t a systematic female effect, altho the book does highlight one – the failure of the unemployment support system to cover single women, who were presumed to be able to rely on family.

Presumably in families where the husband (typically) lost his job, life was very tough for all of the family. On those dairy farms likewise. And yet my mother reports that in her household (as a young child then) there was always a resident maid.

LikeLike

Having talked to my Dad about his experiences of that time, and read a few books on the global Depression, I am left with the view that monetary reflation is the most important line of defence against a depression. One wonders if there is really enough institutional pressure on our technocrats to make sure it doesn’t happen again. Yes, we have the inflation target and the financial stability reports etc. But perhaps we should make it clearer that the authorities are explicitly expected to pull out all the stops to reflate, if “it” does happen again.

LikeLike

Yes, I agree. I think that is also partly the case for erring towards the stimulatory side of things now, not just here. Having said that, recall that some of that mentality was part of what allowed inflation to get away in the 60s and 70s – people who had lived thru the Depression being determined never to be implicated in a repeat. It isn’t an argument against now – in some circles i think the problem is still excess inflation fear among people my age who grew up in the high inflation years – but it is a reminder of the need to read the signs pretty carefully.

LikeLike

Rather than looking at the experiences of larger countries like Canada and Australia, New Zealanders may be more interested in looking at the economic and political experiences in Newfoundland during the Great Depression.

Similar to New Zealand, this small, self-governing colony was carrying large debts and a diminished pool of labour from WWI, while the prices of its fish and forestry exports were also collapsing. These factors, combined with the mood of the population and decisions of the business elites, eventually led to the government fleeing an angry mob and the suspension of responsible government. Fifteen years and two questionable referenda later, the former Dominion of Newfoundland became a Canadian province.

Who knows, had history worked out differently New Zealand could have suffered a similar loss of sovereignty following a default and now be an Australian state.

For more info, see pages 81-83 in Reinhart and Rogoff’s “This Time is Different”.

LikeLike

Yes, I agree that Newfoundland should be on my list. I suspect geography – greater distance – and population (larger than Newfoundland) probably would not have just seen us fold into Aus even if there had been a default in 1939/40.

LikeLike

Australia constitution already accepts NZ as a state of Australia. All we need to do is hold a referendum and decide if we want to part of Australia. It can happen as easily as ticking a box. One of the conditions that prevent us from moving ahead and has been the stumbling block is the requirement to drop The Treaty of Waitangi and other apartied policies that favour Maori more than others.

LikeLike

You should now read John A Lee’s Socialism in New Zealand, first published in 1938, and just see what and how that first Labour Government did what they did. It is fascinating reading. A lot of the men in that Government didn’t even have a secondary education – certainly Lee didn’t. They were self educated.

LikeLike

I did read it years ago. It was a fascinating government – a few good things, some very bad ones, and a mostly effective conduct of the war (albeit more repressive than, say, the British wartime govt).

LikeLike

For those interested in history, as fascinating as it is, I feel your point about our financial generals engaging in fighting yesterday’s battles is perhaps the best point in that post. Times have moved on since 1928, 1939 and the 1970s, yet much public policy rhetoric (i.e. Politicians’ propaganda) still recalls those earlier battles.

While I support inflation targeting to a large degree – but I think movements in wages should be accorded more prominence in our central bank’s deliberations that what is currently apparent – the emphasis is currently asymmetric. For example, after a period of below target inflation, a country should then be allowed to operate slightly above target for a time to restore nominal prices and wages to where they should have been.

I have just this semester completed a longish essay on government debt for a writing paper (300 Macro, more about optimizations than government accounts these days, didn’t pay much attention to the issue, and was US-centric, anyway) and its one its two main conclusion was as yours as regards inflation: too many survivors from bad ol’ days still in powerful offices. I hasten to add this is not to be taken as that I am advocating a free-for-all!

My main conclusion, by the way, was that the most appropriate indicator for debt stress is financing costs/GDP. I excluded financing costs/revenue because governments can and do (like our current one) manipulate that to suit their own political purposes. Of course, this raises the topic of the effects of current and future shocks!

One quibble: for me, the inclusion of Greece as a scare tactic detracts from your analysis. The experience of that country, hobbled by political dysfunction, elites’ corruption, lack of a sovereign currency, and the influence of a baleful Germany makes any comparison of NZ to that country simply irrelevant.

LikeLike

But surely Luc unless you take history into account then you are just reinventing the wheel all the time. And creating havoc each time. I think history is essential to understanding the present.

LikeLike

Yes, I agree, but applying history to current events is fraught with danger. We need to be very careful. For example, NZ today has an internationally respected currency, a largely credible inflation targeting central bank and, especially since MMP, stable governance. The 1930s and 1970s are mainly relevant these days only to historians. IMHO.

LikeLike

Just an observation on your Greece point. My reference wasn’t intended as a scare tactic, but as a rueful reflection on the capacity of human beings to (again) mess up their monetary arrangements. For all its many other problems, a huge factor in Greece’s current debacle is an insufficiency of demand, and being in the euro severely limits their options to do anything about that (in the same way as NZ’s maintenance of too high an exchange rate for too long in the 30s, and the US staying on gold until 1933 posed much the same sort of constraint. There were understandable reasons why each of those choices, past and present, were made, but with hindsight monetary mismanagement made things materially worse and for longer than was necessary.

Doesn’t mean monetary policy can solve all problems. Of course it can’t deal with structural productivity slowdowns. But that wasn’t the 1930s story – and isn’t what marks Greece out now.

LikeLike

The Open Bank Resolution (OBR) recently introduced by the RBNZ is a direct consequence of Greece. Rather than a open cheque book by the government guaranteeing depositors savings. Greece rebalanced their banks balance sheets by giving saving deposits a haircut. OBR allows the RBNZ to do exactly that.

LikeLike

No, that is incorrect as a matter of history. OBR has been in development for probably 15 years, well before the recession/crisis of 2008/09. It was driven by the Bank’s desire to have workable technical options other than govt bailouts.

LikeLike

But OBR was not the tool of choice when the recession hit and bank liquidity stalled. Treasury and the RB reached for a Bank deposit guarantee scheme instead which ended up bailing out South Canterbury Finance’s fraud to the tune of $1.6 billion in taxpayer funds.

LikeLike

You need some context. First, we – and the govt – had allowed normal market processes to work for the clearly insolvent finance companies that had already failed over 2007/08. There was never any question of bailouts, guarantees, or the like. ANd in response to your second comment, the RB has always – wrongly in my view – opposed deposit insurance or the like as a response to bank failure risk.

The retail deposit guarantee scheme in 2008 came about because (a) we were in the middle of a global panic (a word I use advisedly), (b) other countries were deploying guarantees (notably and first Ireland), often with spillover effects on other countries, and (c) specifically because we were advised that Australia was going to announce such a guarantee that day. The advice from the RB gave no reason at the time to think that SCF or the other remaining large finance companies were in negative equity positions, and so once the political decision to adopt a temporary deposit guarantee was made, there was a choice: to cover the finance companies or not. Had we not done so it would have been a near-immediate death sentence, as funds moved quickly to guaranteed banks. With hindsight SCF proved to be in much worse condition than anyone external (including rating agencies) knew, and that situation probably worsened after the guarantee was extended, but with the information we had at the time (and i stress that rider) I still think the decision to (a) adopt a deposit guarantee scheme, and (b) cover finance companies was both politically and economically prudent. At the time, we saw it as very much in line with the Bagehot maxim, hoping to forestall possibilities of serious runs on solvent institutions by a pretty liberal approach.

Of course, there were mistakes around the RDG scheme. Some involved the Minister acting against official advice. Some were officials’ mistakes (and I was very heavily involved, so will take some responsibility).

LikeLike

The timing of the introduction of OBR still points to Greece being the trigger point. Prior to Greece, the RB clearly opted for the traditional deposit guarantee.

LikeLike

Michael, thank your for your clarification on Greece. I did fear that your readers without much, or no, formal economics learning (and mine is admittedly pretty minimal) would see that as a frightening comparison.

Interestingly, though, I see Greece as initially a fiscal disaster, one that their monetary authorities, if professionally qualified rather than just political appointees, must have been banging their heads against the nearest wall over. And rather than an aggregate demand problem, I also see present day Greece as a supply problem: i.e. we peasants can’t demand much if we ain’t got not much money! Fiscal stimulus could fix that, if it was allowed to.

And I agree that monetary authorities cannot solve all problems, but I would further add that that these days, monetary policy is increasingly not the answer at all.

LikeLike

I was led to believe the change in government had a significant change in policy. It certainly looks like it. classical economics rarely works in practice. Bruning found that out bigtime.

LikeLike

Perhaps it is a semantic issue, but I’d include coming off gold (or devaluing in a NZ/Aus case) in an orthodox prescription. Had Germany come off gold in 1930, perhaps things would have been less awful – but it would probably have been politically impossible to do so (even Hitler kept up the figleaf of gold), and Germany’s pre-existing problems were more political than economic.

In terms of NZ, there was probably at least as major continuity as discontinuity around the 1935 change of govt. What is striking is how much unconventional policy was done under the 1931-35 govt. There was already a recovery well underway by 1935 – thru some combination of world recovery and the lower exchange rate. Labour ended up adopting excessively loose macro policies which ran them into the fx crisis of 1938 (and that risk of default in 1939), which then helped usher in the decades of fx controls and import controls.

LikeLike

Michael,

Germany went off the gold Standard but did not devalue and thus got into BOP problems when they got to full employment. They were the only country to do this. It appears Hitler geared the inflation from the measure and the population’s reaction to it.

LikeLike

Thanks for that clarification. Of course, Germany was also heavily into direct trade restrictions, bilateral clearing agreements etc (all ways of trying to manage those BOP pressures). In a sense, the NZ picture was a muted version of that. The exchange rate had been devalued in 1933, but wasn’t later when Labour’s macro-expansionism went ahead (incl thru the global 37/38 downturn), ending in extensive exchange and import controls.

LikeLike

Michael, I can’t remember if I have drawn your attention before, to a very important analysis by Prof. Nicholas Crafts: “Escaping Liquidity Traps: Lessons from the UK’s 1930’s Escape”.

He shows that monetary stimulus had an extremely effective conduit into the economy, in the form of large-scale development of new housing, affordable to a large proportion of the population, at stable land prices Prof. Crafts absolutely nails it that this was possible at the time “because the draconian restrictions of the Town and Country Planning Act 1947” were yet to come.

As we should have discovered by now, regulatory distortion to supply of land for housing, turns urban property into an asset class in which even more destructive bubbles form than in financial instruments, with monetary “stimulus” doing more harm than good.

I will email you a long essay of mine expanding on this important issue. I call it “The Elephant in the Macro-Economic Room”. Again, you might have seen it already; I don’t know.

We have an interesting contemporary working experiment in this to consider – in the USA, there is a set of cities in which urban land prices are anchored by the availability of low-cost rural land to the “housing” market; and we see extremely disparate outcomes to the same monetary stimulus, between that set of cities and the ones with land availability distortions. Monetary stimulus really does seem to have stimulated many cities in the South and heartland, and actual construction of housing is an important part of this stimulus. There are numerous positive multiplier effects from actual housing construction, and obviously the same “added dollars” can either get new homes built and capture this benefit; or they cause zero-sum increases in the value of unimproved urban dirt, with a politically addictive “wealth effect” seeming to compensate for the lack of REAL economic activity in response to the “stimulus”. The latter is of course a form of Ponzi scheme, not a perpetual economic driver.

Besides the new housing construction, another positive impact from the stable-urban-land-price model is that low interest rates lead to mortgages being paid off faster and/or repayment burdens being lower, which must then leave households with a lot more discretionary income. No actual debt increase is required for the “wealth effect” under this model, hence it is the polar opposite of the “Ponzi” wealth effect in the land-inflation model economies.

US aggregate economic data is now next to useless in determining the outcomes of many policy approaches because there are two or more totally disparate sub-economies in terms of the way policy filters through into outcomes. And urban land is not a factor to be sneezed at, not something minor enough to be safely ignored.

LikeLike

The government at the time was boosting housing so it is no surprise it was rising. Bear in mind the UK recovery was weak and classical economics had had it dropping in GDP per cap[ta before the Depression hit. The UK never had a decent recovery after WW!

LikeLike

At least on the Measuring Worth series, UK GDP pc rose right thru to 1929. That said (and like NZ) the 1920s had been a decade of pretty weak performance. Quite how one explains that still seems open to question – eg the role of things like reverting to gold at the pre-war parity, the massive overhang of war debt, the unemployment insurance system which helped price marginal labour off the market.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Utopia, you are standing in it!.

LikeLike