This post is mostly a brief follow-up to yesterday’s, with its comparisons between the performances of Uruguay and New Zealand. I concluded that post noting that it wasn’t obvious what would prevent our continued slow relative decline.

Comparisons of material living standards across time and across countries are fraught with measurement problems. No one seriously questions that 100 years ago we had some of the very highest material living standards, and equally no one really questions that we are long way off that mark now (some want to focus instead on wellbeing indicators: that is a topic for another day, but a country that has as many of its own people leaving as New Zealand has had shouldn’t be seeking to rest on any sorts of laurels).

Historical estimates are fairly imprecise, and only available for a small number of variables (typically GDP per capita). For more recent periods, we have much more, and better-measured, data – although always less than researchers and analysts might want – but even then we face problems in comparing outcomes from country to country. All of which suggests one shouldn’t put much weight on small differences – they might just represent imprecise measurement and translation.

The most common comparative metric is still GDP per capita. It has all sorts of problems, but one in particular is that there is huge variation across countries in how many hours the population works on average. If people in one country on average work twice as many hours as those in another country then, all else equal, the people in the first country will have higher incomes. That provides greater consumption opportunities, but isn’t much of a reflection of the productivity levels being achieved by firms in the countries concerned. For that, the best indicator that is reasonably widely available is GDP per hour worked. It is also much less affected by business cycles than GDP per capita. For international comparisons, one needs to convert the various estimates into a common currency, not at market exchange rates but at (estimated) purchasing power parity exchange rates.

For many countries there are no worthwhile estimates of GDP per hour worked. But the OECD has data for all its member countries (and a few others) and the Conference Board produces estimates for a wider range of countries, going back a little further in history. For the most recent years, they now have estimates for 68 countries. Here is a (long) chart of the 2014 estimates.

I’ve highlighted New Zealand and the countries estimated to have had GDP per hour worked 10 per cent either side of us. That range both recognizes the inevitable measurement imprecision, but also highlights the countries that have a broadly similar level of labour productivity to our own. It is a mixed bag: Cyprus, Japan, Slovenia, Slovakia, Malta, Israel, Greece. But none were ever – well, perhaps not for a couple thousand years in Greece’s case – world leaders. (I haven’t shown the OECD version but the rankings are similar – and Cyprus and Malta aren’t in the OECD).

If the New Zealand numbers are not perhaps quite “middle income” country levels yet, they seem uncomfortably close to them. And they are a huge distance behind those (mostly Northern European) top-tier countries, from Belgium to Switzerland.

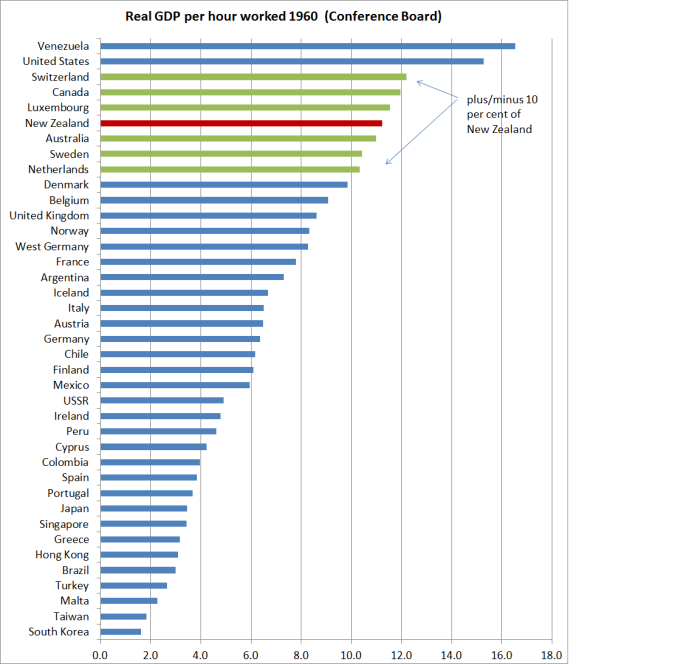

If it had always been so, that might be one thing. Many of the middling countries have always been middling countries. But we weren’t. GDP per capita isn’t GDP per hour worked, but it is fairly safe to assume that our productivity levels 100 years ago would have been among the highest in the world. And much more recently than that, the Conference Board has estimates for a reasonable range of advanced and emerging countries going back decades.

By 1960, New Zealand experts were already writing serious reports on our disappointing productivity growth performance. But then only United States and Venezuela (all that oil) were estimated to have had GDP per hour worked more than 10 per cent higher than New Zealand. In the space of less than one lifetime – and this is more or less my lifetime – our productivity levels have gone from still among the best in world, to lost among the rest. These sorts of declines aren’t normal phenomena. They typically happen when countries mess themselves up badly – think of Venezuela or Argentina, or even Zimbabwe. And, critical as I am of economic policymaking in New Zealand over 50 years, we’ve been a moderately well-functioning country (stable democracy, rule of law etc).

It isn’t that nothing has been done in response to our decline. We stopped doing a lot of what a commenter yesterday aptly called “dumb stuff” – the protection and subsidies that shaped our economy from the late 1930s to the 1980s. But we’ve done our share of other dumb stuff – all well-intentioned. The Think Big energy projects of the 1980s were an example. I class throwing open the immigration doors again 25 years ago in that same category – a new Think Big. A catastrophic decline in relative productivity here was, surely, a signal for resources to go elsewhere – and New Zealanders responded to that signal en masse (as, within New Zealand, people have moved away from places – perfectly pleasant places – like Invercargill, Wanganui, or Taihape as the relative returns have changed). So what possesses our bureaucratic and political elites to think that a path back to prosperity and higher productivity involved searching out and bringing lots and lots more people? If it was perhaps a pardonable error 25 years ago, it is an inexcusable policy failure now.

And then there are the totally flaky ideas that never actually amount to much: turning New Zealand into a financial services hub, R&D subsidies, becoming rich on back of wealthy Europeans fleeing terrorism, and so on. And if that looks like a criticism of the current Prime Minister, he isn’t obviously worse – more practically indifferent to the real issues – than his predecessors, or his potential successors. I watched Q&A interviews with James Shaw and Andrew Little at the weekend, and there was nothing there which gave me any hope that our political leaders even care much any more about our precipitous decline. Bank-bashing seemed easier no doubt.

We can’t, and shouldn’t try, to turn back the clock to 1910, or even (worse) 1960. But we shouldn’t lose sight of what we once had here, or give up believing that we can produce incomes for our people once again as good as those almost anywhere in the world. Governments don’t make countries rich – firms and individuals, ideas and opportunities do that – but governments can stand in the way. I’ve been asked a few times in the last few days what policy remedies I’d suggest. There are lots of smaller issues, but here are my big three:

- Stop bringing in anywhere near as many non-New Zealand migrants. At a third of our current target for residence approvals, we’d still have about the same rate of legal migration as the United States.

- Stop taxing business income anywhere near so heavily. We need more business investment to have any hope of reversing our decline, and heavy taxes on returns to investment aren’t the way to get more of it. The tax system should rely more on consumption taxes.

- Stop stopping people using their own land to build (low rise) houses, pretty much as and where they like.

It is a mix that would produce lower real interest rates (relative to the rest of the world), a lower real exchange rate, a lower cost of capital, lower population growth, and lower house prices. Plenty more innovative outward-oriented New Zealand firms – I heard Steven Joyce talking about them on the radio this morning – would find that a rewarding climate to invest and export, supporting better productivity and income prospects for all of us. Will we match Belgium, the US, and Ireland (see first chart)? Well, perhaps not, but who knows – for all our locational disadvantages, we do plenty of things better than those countries. But we certainly really should be able to do much better than Cyprus, Malta, Slovenia and Greece, if we are willing to take the issue, and challenge, seriously.

Michael

Lot of estimates – how are those “estimated” measures arrived at?

LikeLike

They start from national data – GDP, and labour market measures of hours worked. Countries measure things in slightly different ways. The bigger challenges are the purchasing power parity exchange rate estimates. The ones for recent years rely on the International Comparisons Project led by the World Bank

http://siteresources.worldbank.org/ICPEXT/Resources/ICP_2011.html. Among advanced countries my impression is that the results are reasonably good, but the comparisons of advanced to emerging or poor countries are much more difficult and unreliable.

If one only wants to focus on changes over time, one can cut out the PPP phase and just look at real growth in real GDP per hour worked in national currency terms. Even since 1990, we’ve been about third worst in the OECD. For longer periods – the OECD has data for many of its countries back to 1970 – we look (from memory) even worse, better I think only than Mexico.

They are all “estimates” so we shouldn’t get too hung up on precise numbers, but equally we have to use what we have, and these are the data. Given the exodus of NZers over almost 40 years, the official stats don’t seem inconsistent with the revealed behavioural preferences of NZers (and note that in those charts, Australia has also slipped, just not as badly as we have, so they have still been a useful exit valve option for NZers)

LikeLike

So do you think that dropping our tax rate to say 25% and GST increased to 18% and/or if we had reduced immigration and thereby as a consequence raised our wages by 30% (to match Australian wages) would enable us to keep Fisher and Paykell manufacturing in NZ?

LikeLike

As so often, you leave the exchange rate out of that mix. Our real wages rise only as productivitiy improves.

I don’t know enough about the F&P specific story, but I’d have thought NZ wasn’t a natural location for manufacturing large appliances for sale in North and East Asia. If it were, issues about population/distance/location would be moot.

LikeLike

The exchange rate is a consequence of running a interest rate policy higher than our major trading partners. Pushing GST upwards has a inflationary impact on consumption and therefore would keep our inflation high leading to higher interest rates and a higher NZD. Ignoring our higher interest rates as a major impact on NZ productivity points to to myopic tunnel vision in your thinking.

LikeLike

To the contrary, our high real interest rates relative to those abroad, is central to my model and story. My package of measures would materially lower real interest rates. GST increases push up the price level, and one year’s inflation rate, but if you go back and look at the 1986, 1989, and 2010 GST increases none warranted even a temporary increase in interest rates. Increasing the future cost of consumption tends, if anything, to be deflationary.

LikeLike

That’s not correct, increasing GST filters through to higher prices which is inflationary which in turn does drive up interest rates. As we are already sitting on interest rates higher than it needs to be, an increase in GST tends to lend support to a already high interest rate policy. There would not be a big blip on statistics as you suggest. But you would not expect to see a upward blip if our interest rates are already way over the top. The problem with a higher GST

1. It makes our retailers less competitive and gives a boost to online purchasing which is currently a billion dollar hole for local NZ retailers, that have a $400 exemption and a $700 exemption if you are coming on a flight. My partner bought $3000 of Apple computer equipment in Sydney airport the other day and she just waltzes in through customs GST free. Customs in NZ was too busy looking at fruits and foodstuff and can’t really be bothered about collecting GST.

2. Because of the transparency and access to the lowest priced product offered by the internet and fast courier, manufacturers margins are directly affected with a higher GST regime. Our GST at 15% is already way over the top when compared with our trading partners. There is a incorrect believe that GST has no effect on businesses because it is collected from the end consumer but that assumes that a higher GST rate can be passed onto consumers. The reality is that the consumer now has choices overseas which means that there is a ceiling that prices can be on charged. Any increase in GST reduces productivity as you would sell less as you try and raise prices, your input costs rises as your wages rises due to lack of migration and your output reduces as GST push your prices to be uncompetitive against external manufacturers. Our NZ manufacturer is being squeezed at both ends and ends up decimating NZ industry.

LikeLike

I won’t respond in detail, but I have some considerable sympathy re how far we can raise GST. I’d probably be uncomfortable going above 20%. But a consumption tax is a different issue from GST, with different enforcement issues.

LikeLike

I agree absolutely with your three steps, Michael, and add three more:

4. Eliminate all income taxes including tax on business profits.

5. Increase GST to 33 1/3 % and increase all benefits by about 11% to leave beneficiaries no worse off.

6. Switch to a Sovereign Money banking and monetary system.

This would see this country increase its GDP per capita at a rate faster than ever before, and we could catch up, to be once again among the richest in the world.

LikeLike

I’m pretty sure you’d need to raise benefits by more than 11% to fully compensate for that sort of GST increase. The usual benchmark has been that a GST increase of 2.5% raises the CPI by around 2.2% – and that is probably an understatement as altho rents aren’t subject to GST, new construction is, and by extension existing house prices and required rents will rise.

I’m sympathetic to a much higher consumption tax, but would probably favour a progressive version.

LikeLike

Really interesting charts. I was surprised to see the Northern European countries doing so well, especially as many have taken steps to transition housework to a paid basis. I guess they have a lot of corporates with that magic combination of proprietary tech + brand + distribution, which makes them so productive.

LikeLike

Is there much to be said about the shift of employment toward the service sector? Keep reading that productivity is naturally lower in services relative to ‘industry’? I guess this also implies less capital/debt +equity which means retuns on capital in services can be high even if aggregate productivity measures are relatively low? I.e firms measure results by returns, economist’s by productivity trends

LikeLike

Services is a real mix. There are some areas where it is very hard to measure productivity (growth), some where many countries barely try (often core govt areas), areas where there is little scope for genuine productivity growth (a waitress, or a violinist), and then other sectors with really rapid productivity growth (think of telecoms). Services are typically less capital intensive, so that globally the amount of new investment required for each dollar of new output is less than it was a few decades ago, but since capital is mobile across industries you wouldn’t expect returns to capital to be permanently higher in services than in any other sectors.

LikeLike

I don’t favour a consumption tax. I think a corporate tax of 12-15% would be enough to make a noticeable difference (even though many US multinationals pay less than that). You could fund it by a mixture of asset-testing existing transfer payments; a land value tax, fixing student loans and maybe an increase in petrol tax.

LikeLike

We already have a land value tax. It is called rates.

LikeLike

Rates are in the main a charge for goods and services provided to property – that’s why they (rates) attract GST. Most councils have gone away from land value based rating to calculate the general rate – much more commonly it is charged based on capital (as opposed to land) value. Additionally, many LAs are using fixed charges, UAGCs (i.e., flat fees) and other targeted rates – making the capital or land value value-based component of rates a smaller and smaller proportion of overall rates as time goes on. Bit different for rural – as of course they receive less services, so don’t pay many of those fixed charges for infrastructure. We moved recently from a 100 acre LSB to an 800m2 property in town – and paid twice the rates for the urban property. .

LikeLike

I don’t favour a lower company tax rate per se, since it only benefits overseas shareholders (for NZ owners it is, in effect, just a withholding tax). But I’d be happy with a 12-15% rate on capital income, under a dual tax model.

LikeLike

Not too clear what you mean by capital income? Is that Capital gains which means that you would support a Green Party policy of a CGT tax of 15%?

LikeLike

No, definitely not capital gains. I think there is little or no economic case for taxing them. Capital income basically means profits and interest. In Scandanavia they tax it at lower rates than labour income is taxed. I linked last week to some notes of a presentation I did on the issue a few years ago

Click to access Towards-a-Nordic-tax-system-for-New-Zealand.pdf

LikeLike

Here’s another blow to productivity. The new Health and Safety Act.

Ask businesses what they think of the time wasting this is creating. Ask many about the stupidity that passes for covering your arse from the Nazi’s at Worksafe.

How does having a tear in the seat of your occasionally used forklift constitute a H&S fail?

It this sort of rubbish that is causing our productivity to fall.

sure there is plenty that is good but any fail and a Director can go to Jail.

They are roaming around our town like crazies.

Replace all your electrical leads every three months or have them ticketed. Jees I have some that are years old and still pass the test. Its just gross waste. ( and like the Drug Testing etc a rort that is driven by sectional interests who lobby stupid pollies that have never done stuff and who are naive and gullible.

If you are a builder and have say 35-40 portable tools, some of which you may use only every few months, they still have to be ticketed every 3 months.

Just mindless bulls**t.

We use domestic irons at work, computers, and a phone system (you know those portable two phone handsets), well they all have to be ticketed. even the goddamned vacuum cleaner.

Idiocy of the first order.

But then we can go jump off the waterfall and drown.

Look for many shutting up shop and taking their pension to spend.

wouldn’t go a day without hearing this at the moment.

It just ain’t worth the bother for many small businesses.(who were safe before.) Paper work by the mile and no reward.)

Of course your desk is a workplace so make sure that you have ALL things electrical in your office including the kettle or coffee machine tagged. Write your self a health and safety policy and then hope like hell you never fail at anything that could be attached to that policy in a court.

Of course the Lawyers and Consultants who really need jobs will have another way to suck business dry and lower our Productivity, for their benefit.

Bahh.

LikeLike

Raising Productivity is about working more efficiently at a better cost per product.

In a production system that means investing in better plant and systems including it.

But we don’t do that at all well.

Sure we are good at buying new cars and trucks but not so good at plant.

I would argue that one way to increase the gains is to increase the depreciation rates on fixed plant. Not on 4 wheel cars and trucks but fixed to the floor type plant.

That allows cash to remain to be spent on new plant.

I also think that cars should have their depreciation lessened and leasing costs trimmed or even disallowed. There is no way a lawyer (or anyone else for that matter) should be able to claim the costs of more than an average vehicle against the taxpayer. I would have a ceiling on the amount allowed at say $35000. Watch what would happen to the tax take.

What is magic about 20% as a depreciation rate. Nothing at all

Why should we not be able to depreciate new plant down to nil over 3 years?

If you keep it after that then no benefit to write down and therefore tax to pay. If you sell it and buy more up to date plant then you are most likely increasing your productivity.

Trucking companies survive on their depreciation. 20% of 400-500k gives you a big cash boost so why not allow much smaller businesses to benefit from a good cash flow.

LikeLike

A few thoughts: –

I was interested to see Japan well below Germany in both charts, I’d always thought of both as being similarly successful manufacturing countries. Why was I wrong and why are Japan so much lower than Germany?

Perhaps our success upto 1960s was out of character and since then we’ve been reverting to our norm, or what it should be?

Is our poor growth because businesses are in poor-growth sectors, or because our businesses have been performing poorly relative to global sector averages, or both? Similarly, what were we doing right earlier last century? Is it as simple as saying we had the agricultural produce that the UK/world wanted, a good exchange rate and a good price, and now we don’t?

I was interested to see (according to the web) that at some historical point our exports were 90% agricultural and our exchange rate with the UK dipped as low as 0.8 between the Great Recession until after WWII, because of a drop in demand, but I haven’t found balance of payments type figures going back to earlier last century

LikeLike

Japan has inferior micro regulatory policies (see eg the extremely inefficient and protected farm sector, or retail). Germany, like most N European countries, scores well on regulatory quality. [Altho, on checking some of the indicators this difference is less marked than I had thought].

On your final point, we had really large current account deficits up to around the Great Depression – but that is what you would expect in a new country growing rapidly. Yes, our real exchange rate to sterling was lowered a lot in 1933 and not restored to the previous parity until just after World War Two: our experience of the Great Depression had been much worse than the UK’s, we ran reckless policies over 1935-38 (almost leading to a major default) and then we did extremely well (relative to them) economically out of World War Two.

Was our success to 1960 out of character? Perhaps – and note that I’m uneasy about thinking we could again get back to being among the very highest income/productivity countries in the world – but in a sense that goes to my point: if fundamentals have gone against us, and the opportunities here are less good than they once appeared, it is sensible for NZers to leave, and crazy for the govt to run a large scale programme to bring in lots of new people. People left the Dakotas or Montana, or rural areas all across the US. They left the Highlands of Scotland. They left Invercargill and Taihape. And, apparently reasonably, they have been leaving NZ. Them doing so is, in my view, the best hope for those of us who stay – so long as govts stop doing “dumb stuff”, interfering with the adjustment.

I’ll think a bit further about the answer to your sectoral question. Denmark is one example, and Ireland is another, where agric remains important, but other sectors have emerged much more strongly than in NZ. But they have big locational advantages and we have big locational disadvantages.

LikeLike

It is not a large immigration program when that currently policy is largely replacement. If we look at the specific details. NZ stats indicate 14k immigrants this year arriving from overseas. Government aims for 45k which means the remaining 31k is being offered to foreign students. The reality is Foreign students stay long enough on a work visa to get enough work experience before they depart back to their own countries ie generally they leave. If you drop immigration you are directly reducing the number of students to come to NZ to study shaving at least $1 billion off a lucrative $3 billion dollar industry.

You have written off manufacturing as NZ being too far away from population markets but you do not want migrants to top up our declining population and now you want to discourage international students and you want to force wages to rise to match Australias 30% difference so that we keep our young ones in NZ to maintain NZ population rather than bring in migrants to replace our departing young.

When you refer to short term pressures on our NZ resources you also do not factor in the 31% increase in spending by tourists and forget that tourist numbers have increased by 300,000 from 2.9 million to 3.2 million. I would have thought that 3.2 million tourists with an extra 300k tourists this year (sure it may have been spread over 12 months) running around Auckland would have a bigger impact than 14k new migrants or if you want to include international students 45k.

LikeLike

No, I haven’t written off manufacturing – my comment was about bulky moderately low value items. But this will always be a challenge place to manufacture from, for world markets. And we have limited natural resources, and middling (at best) universities, which I why I argue policy should not be trying to drive up/hold up our population.

LikeLike

I spotted your comment about large current account deficits because we were growing, makes sense. I had wondered about that, I had thought that perhaps if we had high GDP we might have had a curr acc surplus. Perhaps we had low imports (of goods) as the country provided most things that were needed and we were mainly importing capital?

But at the same time as we had rapid growth we had very high GDP per capita. That seems to be a contrast to one of your current positions that immigration is one of the problems indirectly causing a lack of GDP per capita growth. (I hope I’ve got that about right).

Not that “then” and “now” are necessarily the same, but it does make me wonder how they are similar/different, and whether it helps the discussion.

LikeLike

The key difference is new opportunities (and lack of them). late 19th C NZ had a lot of land not being used much, if at all, capable of producing food that Britain demanded, and needing more people to take advantage of those opportunities. The opportunities were magnified by falling transport costs and refrigerated shipping, and technologies in the dairy industry that made large scale high quality dairy exports possible and very rewarding. We were doing so well we could then take many more people and still be among the richest in the world.

But all that was before World War One. We’ve had nothing similar since.

(prob a bit terse, but that is the gist of the story. Happy to elaborate at some stage)

LikeLike

The Tax Working Group rejected a Nordic tax system, from memory. Was that the end of it?

Seems to work well for the Nordics if GDP per hour is a goal – which seems laudable.

LikeLike

The tax working group supported a tax on invested equity in property. It was intended as a tax on all property equity and not isolated to investment property. The intent is too move New Zealanders away from investment in property including your paid up own home and to have that money invested in the so-called productive sector ie small businesses that have a 80% chance of outright failure.

LikeLike

The McLeod review back in 2001 favoured that option – it was a more first principles review, unlike the (effective but limited) TWG

LikeLike

Reply to Blair’s comment

Yes they did – but then the TWG wasn’t really looking at “root and branch” issues (let alone medium term economic performance). The 2025 Taskforce reported more favourably on the option,

Of course, in the Nordics they don’t have low capital income tax rates, just a lot lot lower than their labour income tax rates. But that is no reason why we couldn’t have, say, a 12.5% capital tax rate, and a max labour income tax rate of, say, 35%.

IRD is very wedded to the current approach to tax – and there are areas where I strongly agree with them, eg opposition to CGT – and of course the govt has had no real interest in any more serious thinking about what might be required to turn around NZ’s econ performance.

LikeLike

I thought your 2012 speech was very persuasive. I would have two questions for you in 2016. One, what evidence do we have from other countries that have cut capital taxes – do they in fact result in less revenue, or more revenue? Two, how does this affect the current debate over multinational corporations who derive large profits from OECD countries but seemingly pay no tax.

LikeLike

Will have to think/dig a bit on that. My expectation is less capital tax revenue (which doesn’t mean the strategy is not effective – after all, the long term goal is to raise wages, which are still taxed heavily).

I haven’t thought deeply about the current issue, but I’m really uneasy about measures that seek to raise global taxes on business (there are always some real cross-country allocation issues of course).

LikeLike

Regarding Land use restrictions and density, I attended a seminar held by Auckland Council yesterday. The key speaker was Joe Minicozzi, a urban planner from USA. He has done quite alot of work demonstrating the higher taxable value(rateable value) of higher density sites. He also showed in a very graphical manner the roading, piping, sewerage costs, parking costs and the prohibitive maintenance costs with a low rise city, unregulated and spread widely making US cities bankrupt due to the American car culture. The lower taxable value of low rise cities has led to at least 200plus bankrupt city councils in the USA with more to come.

LikeLike

A guy called Charles Marohn has founded a movement called Strong Towns targeting exactly that. Also in the US context where I think local government pays more of the bill for roads.

LikeLike

The government is the taxpayer. Therefore either the ratepayer pays or the taxpayer pays, either way it is still you and I that foots the bill.

LikeLike

Sounds interesting. Did he have a paper? I’m reasonably skeptical of his general conclusion, but open to evidence – but in any case, density should arise from free private choices, externalities reasonably priced, not because any of us have a view, well founded or otherwise, on whether it is “a good thing”

LikeLike

http://www.forbes.com/sites/citi/2014/03/14/why-downtown-development-may-be-more-affordable-than-the-suburbs/#550bbe287ab3

LikeLike

Thanks

LikeLike

http://conversations.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/events/joe-minicozzi

This is a video of the lecture on that day.

LikeLike

Have you considered the effect of tourists on the productivity calculator? The largest export earner in Singapore is actually Tourism with 15.2 million visitors. NZ only gets 3.2 million. If we take out tourism how does NZ productivity measures up?

LikeLike

Mechanically, various people point out that labour productivity would be lower without tourism than with it (since on average tourism jobs are relatively lowly paying).

I’m not sure I want to use that argument myself – we take what export opportunities we can get – but it is consistent with a line I’ve used that no advanced country of any size gets rich on tourism. (and for a place so remote the challenges are even greater. Last time I looked, France had something like 80m visitors pa)

LikeLike