When you are both a social and institutional conservative, and someone who believes in the central role of private markets in generating prosperity and supporting freedom, and yet live in one of most left-liberal electorates in the country you get used to being in a rather small and embattled minority.

In 2014 Rongotai had the fifth highest Labour+Greens share of the party vote (56.9 per cent, in an election in which those two parties together managed only 35.8 per cent across the whole country). And it was the second-best electorate for the Greens, typically rather more radical and subversive of society’s established institutions and symbols (“progressive”) than Labour: they polled 26.4 per cent of vote here (no wonder we got a dreadful cycleway), only a little behind their vote in neighbouring Wellington Central.

Out of curiosity, I went onto the Electoral Commission’s website yesterday to check out the Rongotai results in the flag referendum. Somewhat naively, I think I was assuming that perhaps 60 per cent of people here would have voted for the alternative flag. In fact, 62.6 per cent of people in Rongotai had voted to retain the current flag. The left-liberals must, in quite large numbers, have joined with the residue of conservatives to support retaining a flag that has been a symbol of our nation since 1902 (a time when we were governed by Dick Seddon, who deferred to no one in his assertion of our nationhood).

Or perhaps it was mostly just party politics.

Here are the 15 constituencies with the highest percentage vote for retaining the current flag

| 69 – Te Tai Tokerau | 78.5% |

| 67 – Tāmaki Makaurau | 77.5% |

| 66 – Ikaroa-Rāwhiti | 76.9% |

| 71 – Waiariki | 75.8% |

| 65 – Hauraki-Waikato | 74.2% |

| 68 – Te Tai Hauāuru | 73.6% |

| 23 – Māngere | 70.8% |

| 70 – Te Tai Tonga | 67.8% |

| 24 – Manukau East | 67.4% |

| 25 – Manurewa | 65.4% |

| 21 – Kelston | 64.8% |

| 8 – Dunedin North | 64.1% |

| 46 – Rongotai | 62.6% |

| 53 – Te Atatū | 61.9% |

| 9 – Dunedin South | 61.4% |

Not a single one is held by the National Party, or would even by marginal between National and Labour.

And here are the 15 constituencies with the highest percentage vote for the alternative design.

| 49 – Tāmaki | 51.9% |

| 48 – Selwyn | 51.7% |

| 2 – Bay of Plenty | 51.4% |

| 11 – East Coast Bays | 51.1% |

| 18 – Ilam | 50.8% |

| 6 – Clutha-Southland | 50.4% |

| 12 – Epsom | 49.8% |

| 52 – Tauranga | 49.7% |

| 33 – North Shore | 49.4% |

| 59 – Waitaki | 49.4% |

| 32 – New Plymouth | 49.1% |

| 57 – Waimakariri | 48.9% |

| 3 – Botany | 48.3% |

| 42 – Rangitata | 48.2% |

| 50 – Taranaki-King Country | 48.0% |

And not one of those seats is held by Labour, or would have been particularly marginal between National and Labour. (In case you are wondering, in John Key’s seat of Helensville, the vote for the alternative design was virtually right on the national average at 43.3 per cent).

Somehow the image of the voters of Selwyn or Clutha-Southland as radicals, keen to ditch symbols of nationhood, seems about as implausible as that of my Rongotai neighbours (or the students of Dunedin North) as conservatives.

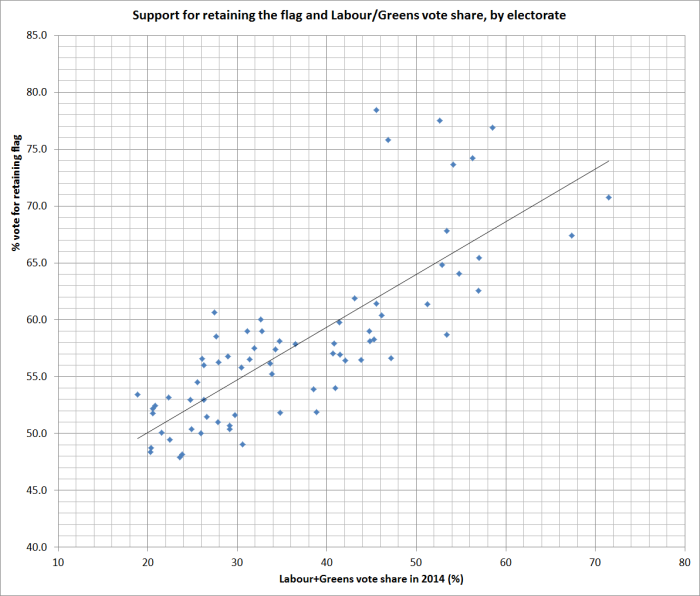

Here is a scatter plot showing the Labour+Greens vote share in 2014 against the support for retaining the current flag, by electorate.

The outliers are the Maori seats, where (a) opposition to changing the flag was particularly strong, and (b) where the Maori Party vote matters.

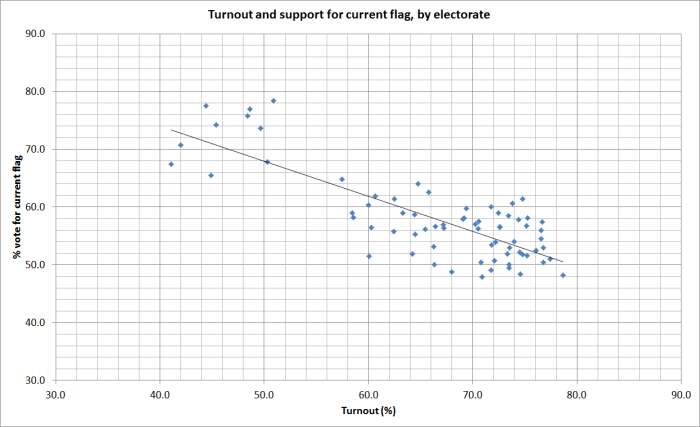

But I was also fascinated by the turnout patterns. This chart shows turnout in the referendum and percentage support for retaining the current flag, again by individual electorate.

I was struck by how strong the downward relationship was. Electorates where people favoured the current flag were also those where people did not participate to anywhere near the extent they did in the electorates voting for change.

Some of that is no doubt just established voting patterns. Older richer whiter electorates tend to have higher turnout rates than younger, poorer, browner ones, and on this occasion this correlated with the pattern of votes on the flag. If the people who didn’t vote had much the same characteristics as those who did (and we have no way of knowing that on this occasion), then if the turnout had been similar across all electorates the margin for the current flag would have been larger (perhaps more in line with the handful of published opinion polls).

All in all, it ends up rather unsatisfactory. Decisions on symbols of nationhood – once in a hundred, or five hundred, year decisions – shouldn’t really split along party lines. Party votes shares come and go, but flags are pretty permanent.

On this occasion I’m fairly sure an underlying majority wasn’t in favour of changing the flag in the first place, and even among those who did really favour change many didn’t like the alternative design. So the final decision probably reflected underlying preferences, even if the actual debate/process did end up all too party-politicised.

I guess we have to blame the politicians for the politicisation. David Cunliffe first promised a referendum, and then John Key copied him, and went on to make the process as much about him as about us, New Zealand. He lost, despite having turned the conservatives radical and the radicals conservative. Very odd.

Perhaps now he could turn his attention to serious issues which really do require a lead from politicians, such as turning around our decades of relative economic decline.

“Alice laughed. ‘There’s no use trying,’ she said. ‘One can’t believe impossible things.’

The only flag worse than yours is our Aussie one.

Did some-one put strange stuff in your dairy prioducts when voting?

LikeLike

Must say I thought it looked quite good on top of Catallaxy Files over the last couple of days! http://catallaxyfiles.com/

Conservative as I am, I’m not wedded to the current flag, but (a) it is ours and has been for more than 100 years, and (b) no one has yet come up with what grabs me as a compelling alternative

Changing institutions and symbols like flags probably should arise organically – a strong consensus builds around an alternative, which politicians then facilitate – rather than being driven by short-term partisan interests (Cunliffe first, and then Key – who did it rather “better”, even if he eventually lost)

LikeLike

I so wish the referendum had been to gauge the country’s interest in real constitutional (as opposed to the symbolic expression of nation-state) change. Toby Manhire reflects my thoughts and disappointments well;

http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/mar/24/new-zealand-flag-britain-status-quo

Personally, I’m glad we didn’t do the symbolic thing before really growing up and doing the grown up thing.

LikeLike

I believe if the vote was about becoming a republic and changing the flag accordingly, there would have been far more interest in voting.

LikeLike

maybe, but the overall turnout was 67.3% (with votes still to be counted), compared to the 78% in the last General Election, so wasn’t at all bad for a single issue vote.

LikeLike

Who says us residents of Selwyn are not radicals

LikeLike

My guess is that currently there are more people opposed to the idea of a republic (conservatives, National liberals like Key, Maori) than were opposed to the idea of flag change, and that a republic is a very distant, if not ephemeral, dream for ardent constitutionally-focused people. We’ve taken back control of our laws and earlier, our GG, so it’s likely to be a hard sell to go to a republic majority – what do we gain in practice, most will ask?

I think flags as symbols can be of powerful value to senses of nationhood, and that we missed a timely (a century since Gallipoli?) opportunity to change the flag that would have built on the cultural progress we have made over the last 100 years in building our own unique identity. While it wasn’t my choice, the alternative flag proposed met my basic test by dropping the union jack and being easily identifiable, and the ‘fern’ was acceptable. It was certainly better than so many ‘three stripes’ vertical or horizontal flags, few of which can be remembered and are often confused one with the other. I think those whose opposition to change was solely/largely because of the proposed alternative will find there never will be a flag with a greater percentage in favour of whatever alternative may be chosen by the majority than the one just rejected.

Michael, thanks for doing this work to show the political divide that tainted what ideally would be a non-political choice. Could there be a way in future to divorce a proposal to choose a flag from the political process?

LikeLike

For me whether we keep the Queen/King of England as our ceremonial head of state doesn’t matter much to me. What I’m more interested in terms of constitutional change relates to balance of powers matters. Our executive branch still has far too much absolute power. MMP has helped somewhat. Our Offices of Parliament were conceived as supposed to help, but they are failing miserably at the moment as the executive just ignores their recommendations. Even the British Westminster system has a second house unable to amend legislation but able to send it back to the House of Representatives if unhappy (a form of veto). We have seen here recently some very serious legislation passed with a simply majority of one – and that ‘one’ has in many cases been from a party with less than 1% of the popular vote. Lot’s of growning up to do.

LikeLike

Clive

Seems to me that in areas like this politicians should really just facilitate a change that has developed informally over time. Rather than seeing it as something politicians should lead on (words I heard Key use this week), they should probably be slow followers. Let alternative designs emerge, and be tested, scorned, refined etc, and eventually perhaps an alternative consensus choice will emerge. It will frustrate enthusiasts for change, but it sounds like a better way to me. It would take considerable self-restraint by politicians, but perhaps this episode will dim their enthusiasm for being at the forefront of such a movement.

LikeLike

I have no doubt that there was also a significant anti John Key factor in this.

consider we needed a discussion on change and that we should do it but the process was appalling. It failed.

Here is a reasonably good summation of that fail.

Wrong people, wrong objective, well we know how govt. continues that story.

LikeLike

The British Empire was great. It brought modernisation and the rule of law till this day prevails. I am proud to have a Union Jack on our flag and have pride with being part of the Commonwealth.

LikeLike

GGS: This is one of those very rare issues on which you and I are, it appears, in total agreement.

LikeLike

Was living in Australia back in 1990’s when they had a referendum on becoming a Republic. The country divided into two halves. The idea of a Republic began with a lot of enthusiasm, it was all the go … for a while .. but it finally broke down because the politicians could not crystallise who would be the Head of State and how the Head of State would be appointed, and what their powers would be

The people wanted a popularly elected Head Of State with full powers

The parliament wanted a ceremonial head-of-state, appointed by the parliament, with no powers

And so the idea foundered, the referendum failed miserably

I wouldnt get to carried away about a Republic unless NZ can resolve those same issues

LikeLike

Missed the link. sorry.

http://www.stuff.co.nz/stuff-nation/14283879/The-12-things-the-flag-process-got-very-wrong

LikeLike

I am on holiday in Sdyney. If you are concerned with Auckland becoming an Asian City. You should come here to Sdyney. The minute I touched down at the Sdyney International airport, I was greeted by sign after sign of Chinese Banks and Chinese construction and Chinese apartment developments for sale. When I walked out onto city streets I thought I had landed in Hong Kong. For every 100 Asian I walked past there was a glimpse of a Caucasian.

LikeLike

I’m constantly hearing this claim that “John Key made it all about himself”, but how is he supposed to have done that?

Certainly, his opponents said that it was all about him and many appear to have voted against the proposed alternative for that reason. But what did he himself actually do, or say, that justifies the accusation?

LikeLike

I think I only said he made it as much about him as about New Zealand, and I think Cunliffe (in kicking the whole thing of) was probably about as bad – both tried to make a key symbol of nationhood into an issue of partisan advantage. But even having kicked off the process, it would have been much more becoming had the PM simply said “my personal preference is my own business only, and I’m just another citizen”, rather than openly championing (down to his lapel badge) one particular option – which has clearly had the effect (together with Labour’s understandable response) of polarizing the vote to a considerable extent along party lines. You can see it both in my chart, but also in the NZAVS results in the Herald yesterday – back before Key started championing change, National voters were (as one might expect) more opposed to changing the flag than Labour and Green voters were.

He could respond that this polarization was never his intention, but he is a smart political operator and will have appreciated the impact of his choices, his phrasings etc. Of course, he usually wins and this time he lost but…nobody’s perfect.

LikeLike

How I read the flag initiative was that John Key raised the flag issue initially as a distraction which moved the opposition and the public away from other mundane and nonsensical issues like “Ponytail Gate”, the TPPA, expensive housing, and moved the topic onto a overriding debate over a flag which worked pretty well because all of us forgot every other issue other than “the flag issue”.

I think he got a bit carried away when it looked like he could actually have the numbers to win it. And by gosh he came close. All credit to him.

LikeLike