Paul Krugman had a piece on his blog a day or two ago making the case for increased (“much more”) public investment spending in the US.

There are three strands to his case.

The first is a proposition that the US is still “in or near” a liquidity trap. I’m not sure I’d use the term, but the general point is one I sympathise with. Under current legislation and central bank practices (easy convertibility into banknotes on demand), few countries are very far from the effective lower bound on nominal interest rates. And if a new downturn comes, that could make it very difficult for central banks to do much to help stabilize economies. To me, that argues for action (legislative and administrative) to remove (or greatly ease) the lower bound constraint.

The second is a proposition that the last few years of disappointing real economic growth are helping to bring about a sustained reduction in future potential growth – in his words,

demand-side weakness now breeds supply-side weakness later, so that there are big payoffs to boosting the economy through public spending

In principle, it might be a plausible idea. But there is no real evidence that things turned out that way during the Great Depression when, extremely weak as demand was, TFP growth remained strong.

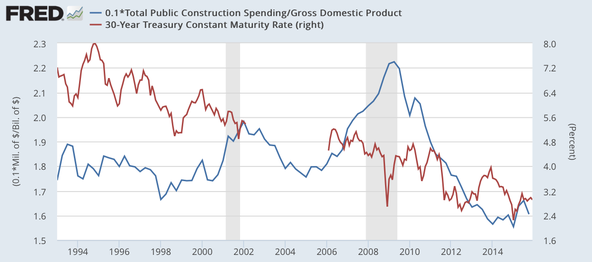

The third – actually first in Krugman’s list – is that public spending as a share of GDP is now very low:

Government borrowing costs are at record lows; markets are in effect pleading with the government to borrow and spend. So why not do it? It’s completely crazy that public construction as a percentage of GDP has declined to record lows even as interest rates have done the same

And he includes this chart

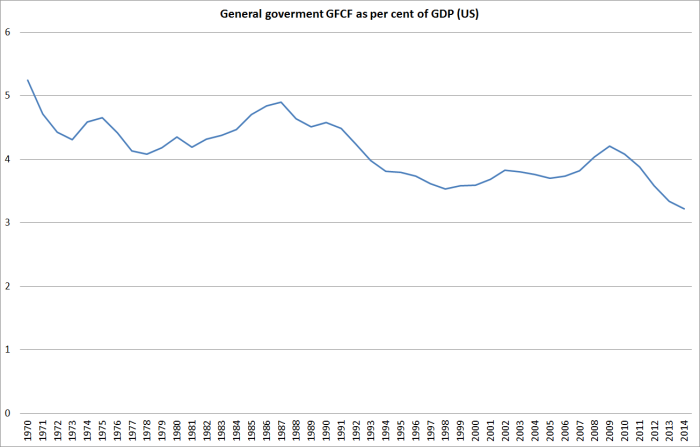

That chart only goes back to the early 1990s. But here, for the US, is general government gross fixed capital formation as a per cent of GDP since 1970.

It is at a record low, which might seem to support Krugman’s case.

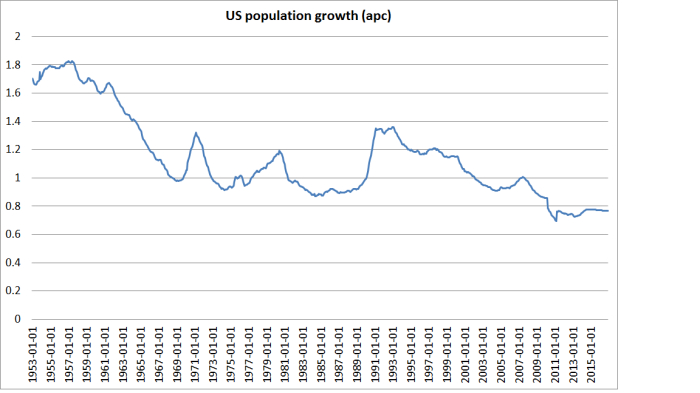

But then here is the annual rate of growth in the US population, in this case going back as far as the FRED series went, to 1953. And what do we find, but that population growth is also estimated to be at its lowest for decades – quite possibly in the entire history of the US.

If the population growth rate slows, less investment (as a share of each year’s GDP) is needed to maintain a desired stock of capital per person. That is a good thing, on the whole – available resources can be used for other stuff. These effects are quite large. Much of the government capital stock is in the form of quite long-lived assets, which depreciate slowly (schools, hospitals, roads etc). Depreciation is one – quite substantial – component of the gross fixed capital formation spending, but a large share of government capital spending is about supporting the needs of a growing population.

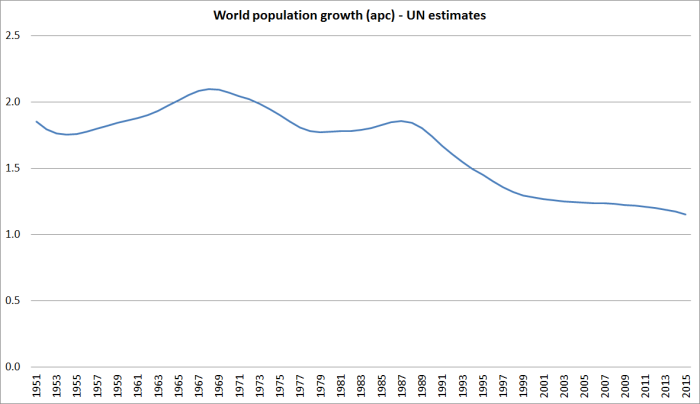

It isn’t just the US population growth rate that is slowing – global population growth rates have been slowing markedly too.

A lower rate of population growth, and associated lower need for investment, is now pretty widely recognized as one of the factors that has been driving real interest rates down around the world. One could argue, with Krugman, that markets are “begging governments to borrow and spend”, but it might be better to interpret is as markets as reflecting the twin declines, in population growth and in underlying multi-factor productivity growth. There simply aren’t as many attractive projects around as there were. It can take time for (desired) savings rates to adjust to that deterioration in investment prospects – and that is usually where monetary policy has a part to play. More government capital expenditure, if the remunerative projects aren’t there, doesn’t look like a particularly attractive way to boost the country’s longer-term economic fortunes. And as the US government is still running deficits, cuts in government savings don’t look particularly sensible either.

Perhaps the US is different, and the high-returning public projects (covering not just the low cost of debt but the overall cost of citizens’ equity) are there and able to be implemented effectively in a way that achieves those returns. But the political process is such that even if, in principle, a large pool of such projects are there, there is no guarantee that those would be the projects that would be picked.

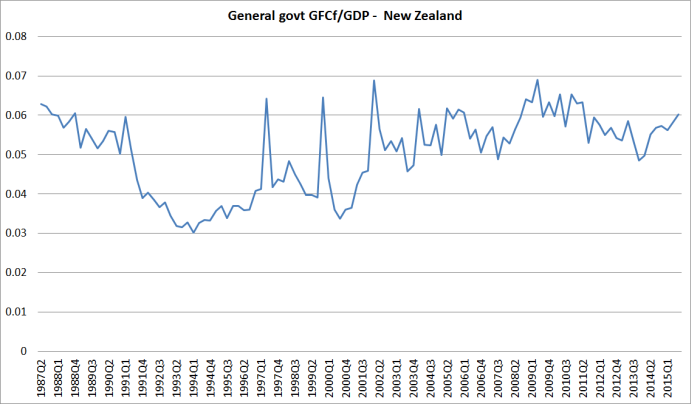

What of New Zealand? Here is the chart of general government gross fixed capital formation as a per cent of GDP back to 1987.

It hasn’t fallen, but then again our population growth – while volatile – has recently been higher than at any time since the 1970s. There is an awful lot of wasteful public capital spending here, that fails to pass reasonable economic tests – Transmission Gully, the Auckland rail projects, the Dunedin stadium, and the fearful prospect of large amounts of ratepayer money extending Wellington Airport’s runway – and we should be wary of the siren calls, even here, to increase government capital expenditure as a way of stimulating the overall economy. Poor quality projects make us poorer.

Are there exceptions – cases where demand might be so weak that perhaps even poor quality projects might help kickstart the economy (Keynes’s example of paying people to dig holes and fill them in again). I’m not sufficiently doctrinaire as to say “never”, but equally it is difficult to think of any actual historical episodes where “sorting out monetary policy”, and complementing that with growth-oriented structural reforms, would not have been a better option. It was in the Great Depression. It would have been in 1990s Japan. It looks that way in most of the world, including New Zealand, now.

Hmmm – just wonder if ‘sorting out monetary policy’ is really being achieved through unconventional polices such as QE, QQE, NIRP, LTRO etc. (with unintended consequences?) Think the fiscal argument can be applied to the euro area (relative to the US or NZ) given its unemployment scourge against an overall fiscal balance / external position that seems sustainable (assuming the union is a going concern): the vision within the Five Presidents Report is encouraging – while noting it is free from the reality of politics! Still, the people rely on their government representatives to implement ‘growth-oriented structural reforms’ so a step toward ‘growth oriented investment projects’ doesn’t seem that great given both should require economic logic which you would think would be quickly reflected in long term government bond yields (something the euro area seems to be attuned to these days…).

LikeLike

I was expecting a skeptical response from you!

Re monetary policy, no I don’t think it is being “sorted out” – there is no sign of the lower bound being effectively removed. MOst of the special measures so far have been signaling – about persistent low rates – more than anything, and some of the euro area ones have mostly been about the union holding together at all, rather than systematically expanding demand.

Re the euro area, yes in principle fiscal policy probably makes some sense in Spain – having given up the monetary tools – but…..to do so would probably not be feasible, since it needs external (to Spain) finance, and the euro itself can’t be taken as a given.

“Growth-oriented investment projects” sounds good, but where/what are such projects. I keep seeing SUmmers quoted as claimed JFK airport is, in effect, one. Sounds plausible, but then you wonder why the airport is still in public ownership anyway, and why private businesses aren’t making the choices to invest or not.

LikeLike

……on your last point, my gut feel is hurdle rates remain ‘high’ relative to where long term rates currently reside: if the private sector believes risk free rates will eventually return to ‘normal’ (and risk premiums are more or less in line with history), there is little incentive to part with cash today unless, in the case of large listed entities, the cash is shuffled to shareholders (nb: some of those hurdle rates in the attached link look eye watering!!)

The private-public-partnership model seems a decent approach as it should provide market disciple while providing confidence to turn the first sod: to that end, the EFSI seems a decent initiative (if you are prepared to think past the Ponzi scheme rhetoric….)

As an aside, I assume GFCF excludes current spending on supporting apprenticeships and higher education? What is the return on this investment into ‘human capital’? I was listening to an article on RNZ the other day re the chronic shortage of maths and science teachers and how NZ has gone from a heavily publicly funded higher education scheme to one where those entering the workforce typically carry a debt milestone around their neck……

LikeLike

Yes, iu’m sure you are right about the hurdle rates. then again, the implied forward risk-free rates (eg second 15 years of a 30 year bond) aren’t extraordinarily low either.

Re your final question, yes GFCf doesn’t include such current spending. I think the thing is that we have gone from generous support for students and trainee teachers (I recall the bursaries on offer when I left school) to a much more costly (to the indiv) training system without the salaries on offer to teachers rising commensurately.

LikeLike

Perhaps there is another way of investing in human capital as a means to stimulate the economy that doesn’t involve supporting the next generation into apprenticeships/higher education. Could government instead offer all school leavers the opportunity to take on a cadetship in environmental improvement (weed and pest eradication programmes, fencing off and planting freshwater margins, planting out eroding coastlines, reforestation of eroding hill country, eradication of wilding pines, etc.). Set the pay for such cadetships at around three or four times the minimum wage and limit the time any one person can spend in the cadetship programme to three years (and only available to NZ citizens between the ages of 17-21).

Effectively all young people starting out have the opportunity to immediately save (if they wish) or spend up large (if they wish). It would also perhaps eliminate the future need for a government-sponsored student borrowing scheme – as every young person would have had the opportunity to earn and save for their own higher education/training. It might also serve to break the welfare dependency (and gang recruitment) cycle as all young adults on that kind of pay could become immediately self-sufficient/independent. Youth unemployment would drop to all time lows, I suspect.

I just keep thinking that if we need to ‘helicopter money’ into the future, one needs a quick fix to get that money into real people’s (and preferably the younger generations) back pockets.

LikeLike

You have to bring into the equation, the interest free rate on the student debt. It does encourage students to take on the debt rather than for parents to fund their child’s education. I encouraged my child currently at Uni to buy a property. The weekly payments received from student loans goes towards paying the interest on the property which she owns rather than being a tenant of another landlords property and she rents out a room to another student.

Of course this assumes property prices rises sufficiently to repay the loan taken out in the future and lo and behold, it has. The rise so far can pay off her student loan debt 5 times over.

LikeLike

The general gist is that you cannot look at a debt in isolation of the assets.

LikeLike

Americans who want more infrastructure forget that it costs around twice what it does in Spain to produce the same project due to the many vested interests. if they focused on getting their costs under control you would see more infrastructure spending even sans government intervention.

Flyvbjerg on megaprojects and risk: http://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv/papers/1303/1303.7404.pdf

LikeLike

Michael

You seem to start with the assumption that civic infrastructure (transport, health, education, justice) all generates a low return. So every $1 a society puts to work in those spheres is a $1 generating a low yield. Furthermore if a $1 heads in that direction it isn’t available for more productive uses. What evidence do you have that such spend is low yielding and what evidence do you have of crowding out?

Looking at Wellington which has an economy based on smart people, isn’t there a case that (A) investing in good transport, health, education, justice attracts such people, and (B) such people attract capital?

Tim

LikeLike

Tim

No, there are plenty of pure public goods (justice as example) and a tendency to underfund them over time (statistics is probably another). Education is a complex one: much educational spending is just consumption and/or signaling, some is genuinely adding skills, but much of that is what consumers (or their parents) would pay for anyway. And even if average educational spending by govt is highly beneficial, there is no certainty that is true at the margin for additional spending.

My skepticism here was specifically about govt capex. Again, we need roads (and airports and ports, but they can/should be mostly privately owned) but do we need Transmission Gully? Whatever our respective optimism or pessimism about Wgtn, it didn’t stack up even on the NZTA’s own numbers. Same for the inner city rail loop in Akld. Or the Otago Stadium. So mine is a practical question: if people thought that for macro reasons govt capex was a good way to go where are the outstanding projects that over high (even just positive) risk-adjusted returns? In the US context, the political process probably makes it even harder to be confident of the answer there than here.

LikeLike

What is the point of the infrastructure being privately owned when they expect the government to pay for any extension? Take for example Wellington Airport which is 67% owned by a private company, Infratil. They refuse to take on the risks of $300 million extension and fully expect the Wellington ratepayer and the taxpayer to take on the risks and to gift that $300 million to Infratil, for the extension So what was the point of that airport being in private ownership. Lets just let the airport deteriorate and let Infratil take on losses and then buy back the Wellington airport for $1.

LikeLike

Or – my preference – let the sharehglders pay for any extensions, pro-rata, and refrain from pillaging the ratepayers (for which, to be clear, I blame the Council)

LikeLike

Chaps

Note we have moved off the point “is it worth building” to the issue of “who should pay”.

The getgreatstuff comments are misplaced or indicate misunderstanding.

The Airport extension is forecast to cost $300m. If airport users who get no value from it (people on smaller aircraft, people buying coffee, parking cars, etc) don’t pay anything towards it, then the estimated present value to the airport company from those who do benefit from the extension and do help pay for it may be about $100m. So on purely commercial grounds and avoiding cross subsidies the shareholders are expected to contribute that sum.

Clearly that makes it a dead duck on a purely commercial basis. Who would hand over $300m for something “worth” $100m?

However, Council has stepped up and effectively said “we believe this will add a great deal of value to Wellington that is not captured by airport charges and we will therefore consider providing some of the funding”. They have then contributed $3 million to a full consenting and evaluation process which looks like taking about 2 years and costing $6 million.

Because Council has finite resources it hopes that Government will eventually also join it in providing funding, in the event that it does make sense and is sufficiently likely to boost the regional and national economy.

Government in the form of Minister Joyce has said “come and see us when you have a deal”.

At present there is no deal. There are not even consents.

It now looks like being about a year before that point is reached and a lot can happen in a year.

Michael has previously indicated he thinks the whole idea is pretty dumb and everyone who wants to fly in/out of NZ should do so via Auckland with odd-balls able to use Christchurch.

But those who believe that consumers may well prefer to enter/exit NZ via Wellington and that having a third international long-haul airport could actually stimulate total demand, those people are best not to jump to conclusions.

On a personal level, I would like to point out the following. Wellington Airport has a fabulous record of adding value to Wellington. It is a major backer of cultural events and a a long term supporter of a number of environmental and social projects. It paid Council almost $12m in dividends last year (about $130 per Wellington household). It is the most efficient jet airport in Australia or New Zealand. On a per passenger basis its charges are lower than Christchurch’s or Auckland’s or most Australian international airports. It has grown international inbound passengers by about 80% over the last five years, an increase of about 4000 people a week, despite a large drop in the passengers carried by the National Carrier.

The Airport has zero intention of deviating from this track record and criticism that insinuates that the extension project indicates stupidity or venal motives is well off track.

Tim

LikeLike

Thanks Tim

As noted, I’m certainly not suggesting venality or stupidity on the part of the WIAL or Infratil, In the case of the Council it is more of an open question, but the sort of boosterism that drives local authorities almost everywhere, with too little hard skeptical analysis, is probably the bulk of the story. I live with the small scale absurdity of the Island Bay cycleway every day.

Whatever the motive, ratepayers’ money looks like disappearing into the project at some point.

I thought Oliver Hartwich had a nice contribution to the discussion today

http://nzinitiative.org.nz/Media/Insights_newsletter/Insights_newsletter.html?uid=1188

Michael

LikeLike