Having highlighted the Reserve Bank’s late Friday afternoon pre-Christmas release of the results of its “regulatory stocktake”, it will be interesting to see what other material government agencies slide out in the next few days, hoping for little or no sustained coverage. I had a reply the other day to an Official Information Act request to Treasury, in which I’d asked about the basis for Treasury’s enthusiastic endorsement of TPP in the Joint Macroeconomic Declaration. What they released wasn’t very interesting or useful (although if anyone wants it send me an email) but they did note “that the official government assessment of the final TPP agreement is contained in the National Interest Analysis, which will be publicly released soon”, which may also mean before Christmas. That document should be interesting – and hopefully it will get some coverage – although coming from those who negotiated the deal it is no substitute for a serious independent analysis and evaluation carried out by, say, the Productivity Commission.

This morning’s Herald was a bit of a surprise. The editorial ran under the heading “Rates rise may be first step to true recovery”. Last week’s Fed Fund rate target increase is, according to our leading newspaper, “the first confirmation confidence is returning to at least one major economy since the global financial crisis”.

Of course, central banks don’t usually raise interest rates unless they think their own economies are doing reasonably well and that inflationary pressures might otherwise be about to start gathering. Perhaps curiously, neither the word “inflation” nor the idea appeared in the Herald’s editorial at all.

But perhaps the leader-writers have forgotten about all those other advanced countries that have raised interest rates in the last six years, only to have to cut them again. Central banks that have set out to tighten generally found that they had made a mistake (with the benefit of hindsight) and have had to reverse course. And it isn’t just the tiddlers. The ECB raised rates back to 2011, no doubt thinking that the crisis was behind them. They were wrong. Business, so we are told, is likely to draw confidence from the Fed’s action last week, and be more willing to invest. It is an interesting nypothesis, but one which bears absolutely no relationship to what has been seen in the various countries that raised rates in recent years only to have to cut them again. Investment rates around the advanced world remain low. It gets tedious to keep mentioning New Zealand’s two policy reversals in the last six years – but there is no sign that either of those ill-judged sets of tightenings did anything very positive for our economy.

Time will tell whether the Fed’s tightening last week was really warranted or desirable. But even if it does prove to have been appropriate, it seems most unlikely that it will have been because higher interest rates and a higher exchange rate combine to give fresh impetus to the entrepreneurs and other investors in the United States. Surely we deserve better analysis than the Herald provided today?

As I noted, investment remains pretty subdued around the advanced world. New Zealand is no exception.

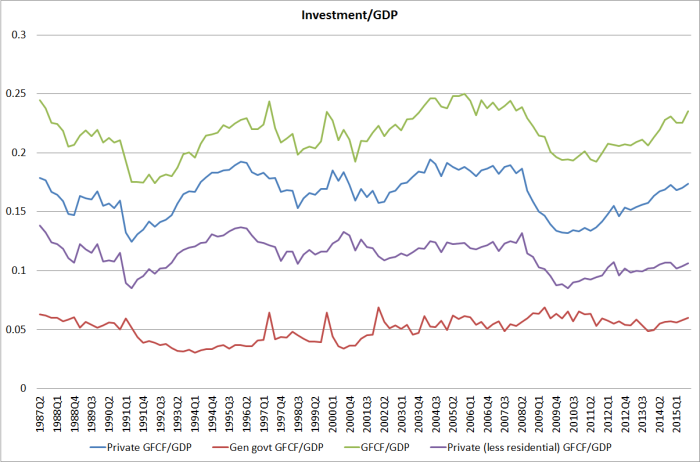

Here are a couple of charts drawn from last week’s national accounts release. The first shows various cuts of gross fixed capital formation as a share of GDP: total, total private, total private excluding residential investment (ie a proxy for business investment) and general government.

With the exception of government investment, all of these series are well below their pre-recession peaks (typically in around 2006 and 2007). In some respects that is really quite surprising. New Zealand has had:

- High average terms of trade, which should typically spark new investment to enable the economy to take full advantage,

- The Christchurch repair and rebuild process (which doesn’t make us richer, but does add hugely to gross investment),

- No serious domestic financial crisis to materially disrupt the credit allocation process, and

- Much more rapid population growth than we had in the last few years prior to the recession.

New Zealand’s population is estimated to have grown at around 1 per cent in 2006 and 2007. By contrast, it is estimated to have increased by 1.95 per cent in the year to September 2015. As I pointed out last week, faster population growth rates would typically be expected to have big implications for investment, since the capital stock is around three times annual GDP. More people require more capital, and getting that capital means a lot more investment.

For good or ill, government investment has remained quite strong, and will be boosted a bit further by last week’s announcement. But my business investment proxy – the purple line – at around 10.5 per cent of GDP (and showing no sign of strengthening) is still two full percentage points lower than we saw through the later pre-recession years, when population growth rates were much lower than they are now. And recall that even this measure includes the non-housing non-infrastructure rebuild expenditure.

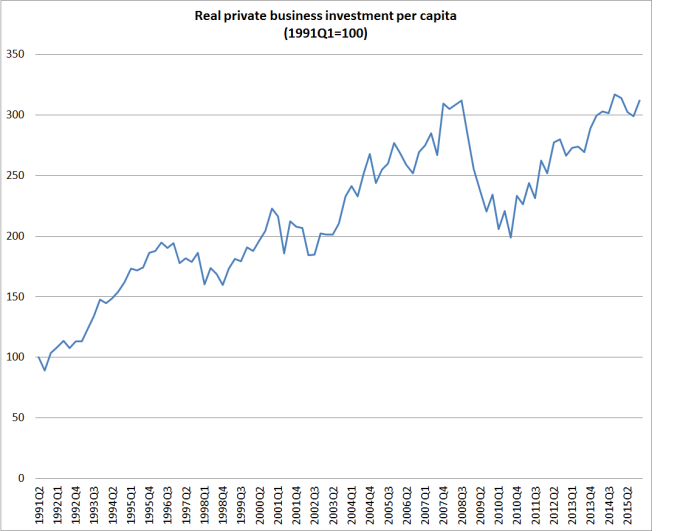

For analysis over time, I tend to focus on ratios of nominal investment to nominal GDP. That is partly on the advice of Statistics New Zealand, who point out that deflator problems – which are particularly serious for investment – make ratios of real investment to real GDP quite problematic over time. But for those with a hankering for real investment measures, here is real private investment (excluding residential investment) per capita. Even now, this series has only just got back to pre-recessionary levels, eight years on. And with the unexpected surge in the population, if everything was working well – and especially if the Reserve Bank was right about supply effects of migration exceeding demand effects even in the short-term – we should have expected to have seen this series at new highs.

Businesses invest to the extent that the expected returns to investment look attractive. In New Zealand, at present, there just don’t seem to be that many projects that have been passing that hurdle. Unfortunately, it isn’t obvious why things should be any better next year.

.

If you overlay the 90 day interest rate onto the investment chart you find that as interest rate rises investment starts to fall and when interest rates stay on the lower end, investments rise.

LikeLike

New Zealand is not investment friendly.

1. Keeping interest rates higher diverts investments in productive investments into savings in banks. Higher savings in banks leads to higher lending. You can’t have one without the other.

2. Fish and bird habitats are put ahead of jobs and productivity, rejecting $100 million monorail to Milford Sounds

3. Harbour views are placed ahead of investments in hotels rejecting key projects like extending the Auckland Harbour to receive larger ships, rejecting the Dunedin Hotel $100 million bid, $400 million waterfront rugby stadium

4. Rejecting mayor Les Mills Britomart $1.1 billion project

5. Blocking mining oppotunities

LikeLike

6. Blocking investments in farms

LikeLike