A couple of weeks ago I wrote about the results of the Reserve Bank’s Survey of Expectations – the quarterly survey of relatively well-informed participants and commentators. Those expectations were still very subdued, with little sign of any expectation that (for example) core inflation would soon return to the 2 per cent target midpoint, which the Governor has undertaken to focus on.

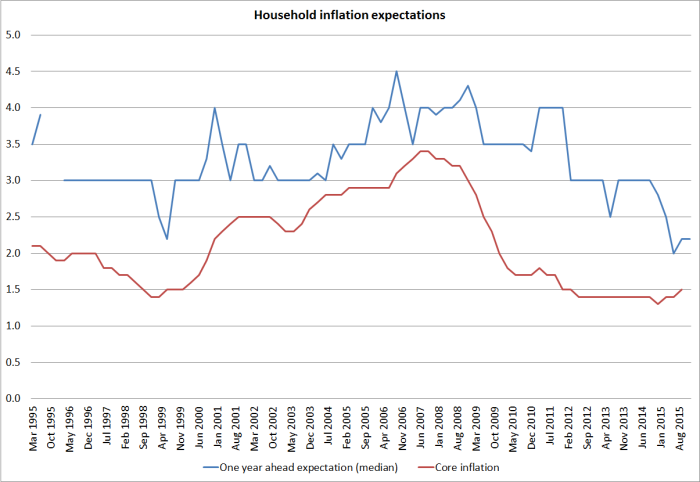

Since then a couple of other inflation expectations surveys have come out. Both the ANZBO business survey and the Reserve Bank’s household expectations survey question on inflation have had an upward bias for many years. Reported expectations are, on average, well above both actual inflation at the time the survey was taken, and above the actual inflation rate for the period to which the expectations related. Both are measures of year-ahead expectations.

The Reserve Bank’s household expectations measures remain very subdued. In the 20 year history of the survey median year ahead expectations have never been lower than they have been over the last few quarters. And when the survey started, the inflation target midpoint was 1 per cent inflation not 2 per cent. Unless the relationship between core inflation (ie excluding the “noisy” bits like swings in oil prices) has suddenly changed, if inflation actually picks up materially over the coming year – as the Reserve Bank keeps telling us it will – these respondents will be surprised.

The survey also asks respondents directly whether they think inflation over the next year will go up, down, or stay the same. Again, there is a systematic bias in the survey – net, respondents have always expected inflation to rise. But outside the depths of the 2008/09 recession – the inflation effects of which people then thought would be short-lived – expectations for headline inflation rising have never been weaker. And, as a reminder, the most recent headline annual inflation rate was a mere 0.3 per cent

The survey now also asks about five year ahead expectations. We only have data since December 2008, but for what it is worth these longer-term expectations have never been lower than they are now.

The latest ANZBO survey came out yesterday. Inflation expectations dropped slightly, and looking at the chart that also seems to be a record low for the series. The Reserve Bank might claim to take comfort from the fact that expectations are still 1.6 per cent, not too far from the target midpoint. They shouldn’t. Again there has been a persistent bias in this series, and no obvious reason to think that that relationship has changed.

At the other end of the range of measures, New Zealand has a 10 year conventional government bond and a 10 year inflation indexed government bond. The gap between the two isn’t a pure measure of inflation expectations, but in normal circumstances it won’t be too far from what investors are implicitly thinking that inflation will be. The monthly average difference for November, as reported on the Reserve Bank website, was 1.40 per cent.

There is talk today of business confidence being a little stronger than it was. Perhaps, but the Reserve Bank’s job is to target inflation, near 2 per cent. It hasn’t done that successfully for some years now, through the ebbs and flows of business confidence, commodity prices, and the Christchurch repair process. And there is no sign in any of the recent surveys and related measures that that failure is about to remedied any time soon.

As the Governor contemplates his final OCR decision for the year, he should be thinking very carefully about these rather disconcertingly low expectations. The Governor often tells us that he wants to stabilise the business cycle. But if inflation expectations do become, in effect, entrenched at levels inconsistent with the inflation target, it can be very difficult – and potentionally quite destabilising – to get them up back again.

On a slightly different topic, I noticed the other day that the Bank of Canada has a page on its website about the extensive research programme it is planning in advance of next year’s quinquennial review of the Canadian inflation target (a non-binding agreement reached with the Minister of Finance). The Bank of Canada has a strong track record of undertaking serious research in advance of these reviews. They plan to undertake significant work on each of the following three topics:

- The level of the inflation target

- Measuring core inflation, and

- Financial stability considerations in the formulation of monetary policy.

The first of these topics particularly caught my eye. As they note:

Canada targets 2 per cent inflation, the midpoint of a 1 to 3 per cent inflation-control target range. Since the last renewal of the agreement in 2011, the experience of advanced economies with interest rates near the zero lower bound has put the 2 per cent target under increased scrutiny. After taking all factors into consideration, the Bank will undertake a careful analysis of the costs and benefits of adjusting the target.

The process is an admirable one. I have previously urged that, with the next (legally binding) PTA due to be negotiated in New Zealand in not much more than 18 months that a similar, open, process should be getting underway here – commissioned jointly by the Minister of Finance, the current Governor, and the Secretary to the Treasury. That would be quite a contrast to the very secretive way these things are typically done in New Zealand – in the case of the 2012 PTA, secretive even after the event.

Doing the work is vitally important, but so is getting it out into the public domain and ensuring open scrutiny and debate of material that will influence the key document in short-term macroeconomic management for the next five years. It would be valuable at any time, but should be particularly so now, after years of undershooting the target, and as the near-zero lower bound moves uncomfortably close again. For example, with the benefit of hindsight was the move to a focus on the midpoint a mistake for New Zealand? I don’t think so, but in view of his track record the Governor may, and there could be reasonable arguments on either side of the issue – particularly in view of the potential interaction with financial stability considerations.

But what I thought was particularly praiseworthy was the Bank of Canada’s willingness to openly acknowledge that questions should be asked, in the light of changed circumstances, as to whether the 2 per cent target midpoint is still appropriate. The issues are a little more pressing for them than for us, since Canadian interest rates are much near zero than ours are, but we cannot afford to be complacent. And if it was decided that a higher inflation target was appropriate, the time to make that call is when there is still conventional monetary policy leverage available. I’d probably still prefer authorities to take serious legislative steps to remove the zero lower bound, but the questions and issues should be asked and examined. In New Zealand to date – including in the Bank’s Statement of Intent – the issues and risks are not even acknowledged.

Interesting about the persistent bias.

“At the other end of the range of measures, New Zealand has a 10 year conventional government bond and a 10 year inflation indexed government bond. The gap between the two isn’t a pure measure of inflation expectations, but in normal circumstances it won’t be too far from what investors are implicitly thinking that inflation will be. The monthly average difference for November, as reported on the Reserve Bank website, was 1.40 per cent.”

I wonder if going long the nominal bond and short the inflation-indexed would be profitable? Could probably leverage quite a bit.

LikeLike

That could be a risky trade – one dovish speech by Wheeler and you are out of the money.

LikeLike

Sounds rather risky to me – over 10 years you would have to be punting on something like an even deeper global deflationary environment, in which the RB ran out of OCR-space. I’m sympathetic to that story, but even if it happened, our exchange rate would plummet (no yield pick up over the rest of the world), providing a boost to the domestic price level. Personally I reckon 1.4% might be about right – with a possible (perhaps impossible to price) that authorities actually move to raise inflation targets at some stage over that period.

LikeLike

So I guess you’re saying that the market forecast (in the price) is about right, but that surveys have persistent bias. Sounds plausible to me. But if there was a persistent bias in the market forecast, then this could be a good trade if transaction costs could be kept low.

LikeLike

In an uncertain world, stick to investment fundamentals, food, health and shelter.

LikeLike

Perhaps the RB should stop thinking and worrying about a non existent inflation problem and start focusing on what is important to grow the economy.

LikeLike

Not sure why Andrew Little has left Grant Robertson in charge of finance because clearly he does not have a clue. Perhaps social welfare or education would be better for him.

LikeLike

I must admit, I don’t really fully grasp the concept of inflation expectations especially how such expectations are formed, by whom, and over what future period: seems a bit beyond day to day life and not really BBQ chit chat. That said, I was born in the late ‘70s so haven’t experienced periods of high and volatile general price inflation, though, can relate to house price inflation which does tend to fare up the odd BBQ!!

Seems major central banks all want to ‘anchor’ inflation expectations at policy targets (predominately 2%) but in light of structural changes since the early ‘90s, is this possible with the toolkits on offer or actually desirable? Global supply chains, capital mobility, lower search costs via the internet, a drive toward firm level rather than collective wage bargaining, and broad acceptance of ‘flexible product markets’ seem to point toward the general price level falling rather than rising: and why should that be a problem?

I guess at the end of the day inflation is likely to be ‘always and everywhere’ positive as it will be difficult for any government – mainly borrowing in nominal terms – agreeing to any other arrangement other than that in which debts can be repaid with legal tender which has depreciated at least a little bit……

LikeLike

re your last para, I’m not so sure. after all, for the last 6-8 years inflation has been lower than was expected [priced], and govts have done little about it. And Japan – for better or worse – got reasonably well-entrenched, albeit modest, rates of deflation

LikeLike

…true that, though, action may yet be taken: per the Bank of Canada example, “the level of the inflation target” is under review – I bet you a chocolate fish won’t be lowered…!!! 🙂

LikeLike

In an uncertain world stick to investment fundamentals, food, health and shelter.

LikeLike

There is talk today of business confidence being a little stronger than it was. Perhaps, but the Reserve Bank’s job is to target inflation, near 2 per cent. It hasn’t done that successfully for some years now,

The best question is; why target inflation?

It ain’t what it used to be as the saying goes and in our history targeting inflation, that in general is imported from other parts of the world, has resulted in a poor performing economy dependent on stealing other peoples money to prop up our extensive social welfare system by transferring that money to others.

That money needs be invested by those that will take the risk..

(As soon as the economy looks like its on the go a clown at the RBNZ decides to kill the bloody economy. Right from Brash onwards.Its efficiency and new product that beat inflation not strangling the baby before it gets out of its baby clothes. i.e. remove subsidies, labour rules, open the door to real competition, invest a hell of a lt more into science and technology and innovation, not by govt. grant but by providing for better business rules about the process, reward those that do this.Remove incentives to invest in flash cars ( by lowering depreciation on them and upping the depreciation on fixed plant. allow it to be tossed in 3 years like Germany does.)

Stop targeting the invisible and start targeting growing wealth for Kiwi’s. with deflation looming large all round the world we had better change our tack quickly or we will be in for another 35 years of lousy economy till something else comes along.

Playing the fool with interest rates, (which allows banks to screw us all), doesn’t encourage business to take a risk nor innovate, incentives do.

Target wealth creation. Only way to go.

Do I think I will ever see a Politician or a Public Servant realize or do that?

Unlikely.

LikeLike

Targeting wealth creation is fine – just not a goal monetary policy can sensibly pursue (directly).

LikeLike

Is there any justifiable reason to have “Monetary Policy” other than to create a barrier to wealth?

It is just another socialist construct to control OPM.

LikeLike

Two arguments typically:

– to better manage financial crises (the US argument in 1913)

– to allow more flexible econ responses to very adverse shocks (eg the ability to lower the exchange rate in the Great Depression) – something like the background to the RBNZ,

Have central banks, net, been good for the world? I think that should be treated as an open question.

LikeLike

Income or perhaps economic growth targetting may be a more preferable option.

http://www.interest.co.nz/opinion/78932/nzier-labels-inflation-targeting-no-longer-fit-purpose-says-rbnz-should-target-income

LikeLike

I am going to do a post about that paper later in the week.

LikeLike

Can I offer a slightly alternative view? (And yes it might be biased by my personal circumstances a little.)

I am quite content with reported inflation at 1% or a bit lower. I don’t see any benefit in a higher rate. For example, when I look at my power bill, it is way higher than it was two years ago. My health insurance has increased 30% over the last two or so years. Contents insurance more than doubled. Rates went up 8%, with barely any movement in the capital rating. Data released by MBIE suggests that petrol prices are overpriced still, with importers’ margins increasing significantly over the last two or three years… My “personal” inflation “feels” quite a lot more than the official figure (the risk of deflation seems remote). Perhaps this effect might be a partial explanation of the persistent upward bias in household expectations. Historically household inflation expectations look quite resilient, and for what it’s worth they have increased since June 2015 a little, if not since September.

Could I also make a comment on the exchange rate? The nominal rate has already fallen a great deal this year and I’m not persuaded adjusting OCR settings to induce a further fall in the real exchange rate so as to boost prices in the shorter term is desirable – if this leads to higher inflation then it ultimately reduces our international competitiveness I thought. (Or is there a short-term/medium term dimension I have overlooked?)

I understand the adverse link with unemployment if the OCR is set too high, but I wonder whether a preferable means of reducing unemployment would be to reduce and better target immigration in much the same way as you have suggested in other posts. Wouldn’t this option, all else equal, have the positive effect of enabling the labour market (particularly real wages) better respond to genuine skill supply constraints? And lower unemployment would also potentially stir inflation, right?

LikeLike

Thanks Kenneth.

If there is any bias in the CPI, formal research suggests that it tends to slightly overstate inflation. But, either way, the CPI-based target is the one the RB is supposed to deliver on. As I’ve noted, one could reasonably argue for a higher target.

Re the exchange rate connection, Reserve Bank research in the last couple of years suggests that when the exchange rate falls there isn’t much of a pick-up in inflation. That seems to be because the exchange rate mostly falls when the economy is weakening, so that although the prices of some imports rise, other inflationary pressures are weakening.

As you say, I do favour cutting non-citizen immigration inflows. But in the short-run that would tend to raise unemployment a bit (or at least require the Bank to cut the OCR to offset the effect?). There would be fewer people on the labour market, but there would also be less spending, and all the research suggests that in the short-term at least the latter effect outweighs the former effect.

LikeLike

[…] ideal (and few are directly comparable across countries), but together they have been providing a reasonably consistent picture of weak, or weakening, expectations of future inflation in New Zealand. No one knows quite to what […]

LikeLike