I finally caught up yesterday with Grant Robertson’s interview on The Nation.

There was the odd good aspect. It sounds as though the variable Kiwisaver policy, as a tweaky tool to supplement to monetary policy, is heading for the dustbin, joining the capital gains tax proposal. Other bits bothered me – in particular, the lack of any sense in Robertson’s comments of the importance of markets, competition, relative prices etc. He is clearly a believer in the power and beneficence of “smart active government”.

And I’m still a bit uneasy when I hear Robertson talk about changing the Reserve Bank Act to place a specific onus on the Reserve Bank to promote employment (or reduce unemployment). It will be important to see details. In principle, an amendment to section 8 of the Reserve Bank Act to say something along the lines of “achieve and maintain a stable level of prices, so that monetary policy can makes it maximum contribution to sustainable full employment and the economic and social welfare of the people of New Zealand” might do no harm. It would, in fact, be not dissimilar to words that have been in the Policy Targets Agreement in the past. On other hand, requiring the Bank to, say, actively target the lowest rate of unemployment consistent with maintaining price stability would be another matter. Right at the moment it might be quite good advice to this Governor, who seems particularly uninterested in the plight of the (cyclically) unemployed. But over time it would risk imparting a bias to the Reserve Bank’s choices that might well lead to persistently higher inflation outcomes over time. That wouldn’t help anyone.

But the bit of the interview I was most interested in was the discussion around a possible different approach to help facilitate people moving from one job to another, as technology and opportunities evolve and change. Robertson seems taken with the Danish “flexicurity” approach. I didn’t know much about it, but in my younger days the idea of active labour market policies had had some appeal, so I thought I would take a quick look. In some respects, Denmark’s experience is one to try to emulate: prior to World War Two it was largely an agricultural economy, heavily reliant on agricultural exports to the United Kingdom, but poorer than us. Now, while agriculture still plays an important part in the Danish economy ,other sectors have become much more important in the external trade and Denmark’s per capita income is far higher than New Zealand’s.

Here is how the Danish government describes “flexicurity”

A Golden Triangle Flexicurity is a compound of flexibility and security. The Danish model has a third element – active labour market policy – and together these elements comprise the golden triangle of flexicurity.

One side of the triangle is flexible rules for hiring and firing, which make it easy for the employers to dismiss employees during downturns and hire new staff when things improve. About 25% of Danish private sector workers change jobs each year.

The second side of the triangle is unemployment security in the form of a guarantee for a legally specified unemployment benefit at a relatively high level – up to 90% for the lowest paid workers.

The third side of the triangle is the active labour market policy. An effective system is in place to offer guidance, a job or education to all unemployed. Denmark spends approx. 1.5% of its GDP on active labour market policy.

Dual advantages The aim of flexicurity is to promote employment security over job security. The model has the dual advantages of ensuring employers a flexible labour force while employees enjoy the safety net of an unemployment benefit system and an active employment policy.

The Danish flexicurity model rests on a century-long tradition of social dialogue and negotiation among the social partners. The development of the labour market owes much to the Danish collective bargaining model, which has ensured extensive worker protection while taking changing production and market conditions into account. The organisation rate for workers in Denmark is approx. 75%.

The Danish model is supported by the social partners headed by the two main organisations – The Danish Confederation of Trade Unions (LO) and The Confederation of Danish Employers (DA). The organisations – in cooperation with the Ministry of Employment have also jointly contributed to the development of common principles of flexicurity in the EU, resulting in the presentation of the communication “Towards common principles of flexicurity” by the European Commission in mid-2007.

And here is a link to an accessible VoxEu piece from a few years ago on the flexicurity approach and Denmark’s experience after 2007.

The Danish “flexicurity” model has achieved outstanding labour-market performance. The model is best characterised by a triangle. It combines flexible hiring and firing with a generous social safety net and an extensive system of activation policies. The Danish model has resulted in low (long-term) unemployment rates and the high job flows have led to high perceived job security (Eurobarometer 2010).

….

The employment protection constitutes the first corner of the triangle. For firms in Denmark, it is relatively easy to shed employees. Not only notice periods and severance payments are limited, also procedural inconveniences are limited. The employment protection legislation index of the OECD for regular contracts is only 1.5. The Netherlands and Germany, countries with employment protection legislation, have an index of 2.7 and 2.9 respectively.

And here I started getting a bit puzzled. Denmark certainly makes it a lot easier than many European countries to shed employees. But it is even easier in New Zealand. On all 4 components of the OECD’s indicators of employment protection legislation, New Zealand ranks as less restrictive than Denmark – quite materially so by the look of it.

The OECD indicators on Employment Protection Legislation Scale from 0 (least restrictions) to 6 (most restrictions), last year available Protection of permanent workers against individual and collective dismissals Protection of permanent workers against (individual) dismissal Specific requirements for collective dismissal Regulation on temporary forms of employment OECD countries Australia 1.94 1.57 2.88 1.04 Austria 2.44 2.12 3.25 2.17 Belgium 2.99 2.14 5.13 2.42 Canada 1.51 0.92 2.97 0.21 Chile 1.80 2.53 0.00 2.42 Czech Republic 2.66 2.87 2.13 2.13 Denmark 2.32 2.10 2.88 1.79 Estonia 2.07 1.74 2.88 3.04 Finland 2.17 2.38 1.63 1.88 France 2.82 2.60 3.38 3.75 Germany 2.84 2.53 3.63 1.75 Greece 2.41 2.07 3.25 2.92 Hungary 2.07 1.45 3.63 2.00 Iceland 2.46 2.04 3.50 1.29 Ireland 2.07 1.50 3.50 1.21 Israel 2.22 2.35 1.88 1.58 Italy 2.89 2.55 3.75 2.71 Japan 2.09 1.62 3.25 1.25 Korea 2.17 2.29 1.88 2.54 Luxembourg 2.74 2.28 3.88 3.83 Mexico 2.62 1.91 4.38 2.29 Netherlands 2.94 2.84 3.19 1.17 New Zealand 1.01 1.41 0.00 0.92

And then I wondered about just how the unemployment rates of the two countries had compared.

At least for the last 15 years, our unemployment rate has hardly ever been higher than Denmark’s.

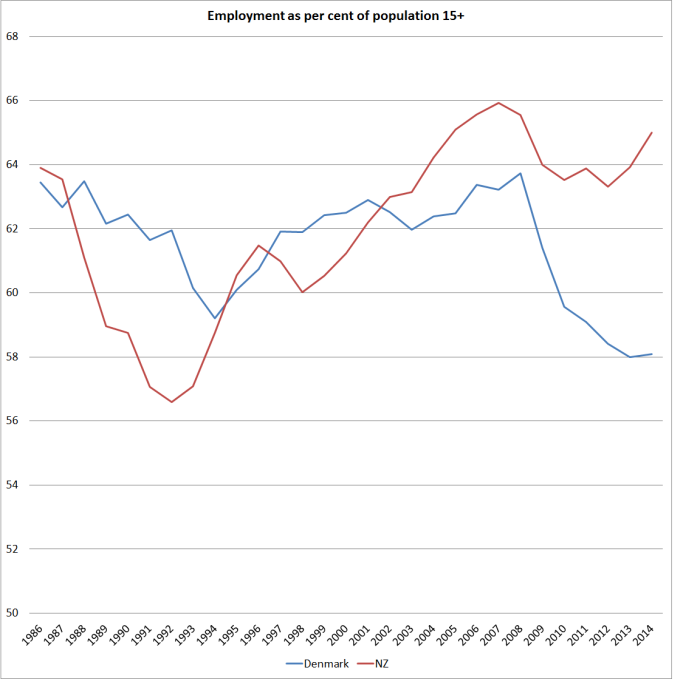

And what of the share of the population in employment. There the difference in recent years is quite startling, and all in favour of New Zealand. The sustained fall since 2007 in the Danish share of the population that is employed is among the largest in the OECD, matched only by Greece, Ireland and Spain.

Of course, the recent employment (and unemployment outcomes) aren’t just the result of employment protection legislation and active labour market policies. Demand is an issue too, and by pegging to the euro Denmark gave up the ability to use monetary policy to support demand (and the euro area authorities have largely exhausted their capacity). I guess the Danish unemployment rate isn’t too bad, but I wasn’t quite sure what the Danish labour market experience had to offer that should attract New Zealand.

I imagine that life on the unemployment benefit is a bit more pleasant in Denmark than in New Zealand, but it isn’t obvious that the Danish structure, as a package, is producing, over time, better outcomes than what we have here. And their model is vastly more expensive, and more heavily regulated, consistent (of course) with Denmark’s position as the OECD country with the third largest share of government spending as a per cent of GDP (57 per cent). New Zealand, by contrast, has total government spending of around 41 per cent of GDP

Perhaps more regulation and more spending was Robertson’s point. I guess we have elections to debate such preferences, but it seems a stretch to believe it would be an approach that would make our labour market function better. It isn’t obvious Denmark’s does.

Labour needs to do what Helen Clarke did and that is to get the Greens to agree not to seek cabinet ministerial positions but would still support Labour to form a coalition government. Labour looks too much like the Greens to be able to attract the center vote which means the Green vote is being split between Labour and the Greens with both parties being decimated. In order to capture the Center votes from National they must be seen to be a strong independent party capable of governing. At the moment they look like a Greens lackey.

LikeLike

Labour and Grant Robertson getting off Capital Gains Tax is not believable because everyone knows they want to tax property heavily. Who is going to vote for a party that clearly do not believe in the policies they are putting forward?? They come across as liars.

The Bright Line test by National is more acceptable because everyone knows it is cosmetic tax policy and really intended to quieten the RB and Treasury economists who are influenced by the share portfolio industry and National do not really want a CGT and being pressured John Key has succumbed. Far more acceptable to the center vote as that 2 year rule would more than likely push prices up even higher as supply is crimped due to no one selling the next 2 years.

LikeLike

I think the Compulsory Variable Superannuation rate is a brilliant idea that encourages real savings that would actually go towards more productive assets. Higher interest rates just encourage more bank savings that is a liability and a cost to the bank which inevitably leads to more indiscriminate lending as we have seen during the Allan Bollard fiasco when banks went low documentation loans as interest rates rises, they panic as their costs start to rise and their margins eroded.

LikeLike

I was expecting a commenting from you on that policy!

Among the many problems I see with it is that it just would not work (to relieve any material amount of pressure on monetary policy). The people it will hit hardest are the people at the bottom, with no additional liquidity buffers, but for people at the upper end of the income scale, it is just a minor convenience – the govt forces you to put money in one bucket, and you make up for that by drawing it out of another bucket. Labour even seemed to recognise the essential unfairness last year, and talked about easing the burden on people at the bottom – which is fair, but undermines the whole point of the policy (temporarily dampening demand).

LikeLike

“Temporarily dampening demand??” The problem with being a super well paid economist in a ivory tower, there is a tendency not to notice the carnage out in the real world when interest rates hit 9%. The construction industry was single handedly decimated by Allan Bollard. Life savings to the tune of $6 billion was lost in a series of 60 plus finance company collapses. Divorces were rife and families ripped apart when they had to deal with job losses and loss of self esteem plus loss of homes. All this well prior to the GFC but of course conveniently blamed on the GFC.

LikeLike

I’m a voluntarily retired unpaid homemaker……

But yes, there was a lot of damage. Booms and busts are like that. The issue here is whether variable Kiwisaver could have made much substantive difference. I don’t think so. I don’t think anyone at the RB now thinks so.

LikeLike

I have already done the maths on it. A percentage change in a Variable Superannuation rate has almost an equal impact as a percentage change in interest rates on available consumption dollars of the average NZ household and also on businesses. In fact it has a fairer impact on all businesses whereas interest rates unfairly affect the profit margin of companies that rely on debt to fund their businesses and give cash businesses an unfair advantage.Businesses should compete fairly in the market with like products instead of having a RB decision that affects the cashflow and profit margin by a stroke of a pen by the RB.

LikeLike

But you always focus on the income effects, and don’t give attention to the substitution effects. Most models will put more weight on the latter. And, since there would be no exchange rate effect, the change in a variable Kiwisaver rate would have to be materially larger than any change in interest rates to get the same effect (even if I were to grant that the income effect was material).

LikeLike

Take Singapore as an example. They currently have Employer contribution of 8% and employee contribution of 8%. Prior to the GFC Singapore had Employer contribution of 15.7% versus employee contribution of 15.2%. How is that policy unfair to people at the bottom when Singaporeans at the bottom can retire financially comfortably compared to kiwis that will retire paupers??

LikeLike

Two separate issues. One is about compulsory Kiwisaver. I don’t support that, partly because Grant Scobie at Treasury already showed that with NZS people at the bottom already have much the same standard of living in retirement as they do before 65. It takes a lot of savings to generate an indexed annuity of $25000 per couple.

But the Labour policy tool was a variable Kiwisaver, and there I don’t think anyone has produced evidence that it will work – especially not to dampen demand in boom times. Plus, from memory they proposed that the RB should be the one using the tool (in conjunction with Tsy). If it worked, it would take some pressure off the exchange rate in booms, but the tool would still mostly rely on Rb judgements and forecasts.

LikeLike

NZ governments should probably avoid unduly meddling in the labour market but perhaps they should not shy away from polices that can encourage targeted employment growth “..as technology and opportunities evolve and change” which seems to be something many countries are facing at the moment. Having recently returned from the UK, the Conservative backed ‘Northern Powerhouse’ idea seemed like a decent government initiative to create employment north of London in evolving sectors. Whether the market would have got there in the end is a matter of debate but governments can be useful in kick starting such initiatives – perhaps because the public sector horizon should be longer and wider than that used in the private sector. Wishful thinking perhaps!

LikeLike

On a (sort of) related topic, this article caught my attention;

http://www.stuff.co.nz/national/crime/73808611/corrections-cuts-community-work-supervisors-hours-as-offenders-fail-to-show

Jobs are going to be lost because:

“Offenders in the region turned up for community work 29 per cent of the time on average. That is below the national rate of 36 per cent, according to Corrections figures, the union said.”

So nationally, nearly 70% of those sentences are never completed? Or are we following the ‘no shows’ up (and I assume) sending the offenders back through the court process? All very costly … and I’d say a re-think on that issue is probably needed.

LikeLike

Denmark intrigues me as a reader of history and economics.

Denmark between Ireland and New Zealand was a major supplier of agricultural goods to the UK. James Belich in “Replenishing the Earth” describes how in 1900 how Britain took 75% of Denmark’s food exports (mainly bacon and butter) and this accounted for 60% of Denmark’s total exports (P.447).

Yet somehow Denmark has been able to diversify its economy away from agricultural exporting dependence in the past century and increase its per capita income in a way NZ has not been able to.

Shouldn’t finding out how Denmark achieved this feat be a serious topic of investigation from NZ’s economic profession?

If it isn’t flexicurity what is Denmark’s secret?

LikeLike

Various people have looked at it from time to time. In all honesty my impression is that people – probably including me – tend to see what they want to see. I don’t think there is yet a remotely definitive study.

My story would put some considerable weight on the interaction of population and location. SInce 1870 NZ’s population has grown from 15% of Denmark’s to around 80%. We probably have more agricultural potential than Denmark – a lot more land – but that persistent rapid population growth crowds out efforts to develop other exports more rapidly (or even to make agric more capital intensive), through a mix of high real interest rates (or credit rationing pre 84) and a persistently overvalued real exchange rate.

And our distance from markets means more of an uphill battle to develop those alternative industries, even if the macro policy environment had been more conducive.

LikeLike

Thanks for the reply Michael. My wife is Finnish so I know what you mean by an unconducive macro policy.

My focus has been on affordable housing. I also favour decentralisation. It is my belief that the obvious poor policies (and culture from residents) for urban planning in NZ and a historic tendency to overly centralise all areas of government control has meant NZ lacks urban frameworks which would facilitate a modern, innovative based diversified economy. Hence we are stuck with being overly reliant on agricultural exports -despite the obvious problems of squeezing additional growth from that lemon to maintain our first world status.

But as you say there is probably a tendency to see what I want to see.

My one hope is that affordable housing despite having a disturbing large number of vested interests supporting the status quo is within NZ’s power to reform. Whereas places like Finland are stuck with the euro macro-policy that has a whole continent of vested interests preventing effective reform.

LikeLike