I was reading this morning Robert Waldmann’s critique of Olivier Blanchard’s defence of the IMF’s involvement with Greece since 2010. I agreed with much of what Waldmann had to say, and remain fairly unpersuaded by Blanchard’s case.

But one of Waldmann’s comments caught my eye. It was the suggestion that Greece has achieved a massive internal devaluation over the last few years.

I’ve pointed out previously that that doesn’t seem right. The measure of a successful internal devaluation is surely in the degree of resource-switching that has gone on.

Those wanting to put an optimistic gloss on the data can certainly produce real exchange rate measures that seem to show some gains in competitiveness. Perhaps, but it is difficult to adjust for compositional effects (the least productive people will have lost their jobs, but presumably want to be employed again one day).

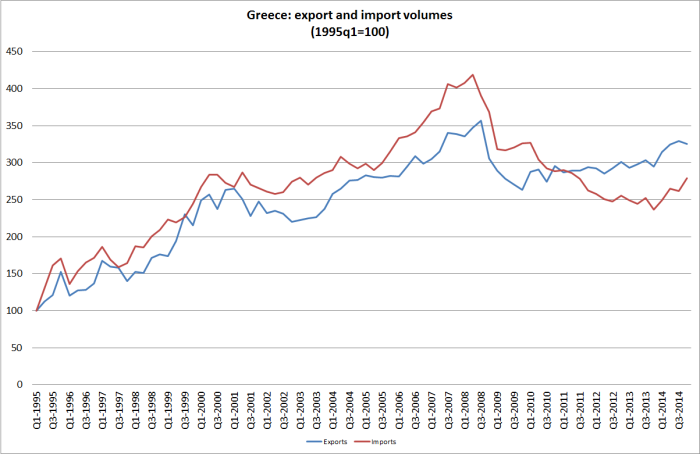

These two charts just look at some of the key aggregates, drawing from the OECD’s quarterly national accounts database.

Exports have been recovering somewhat since the trough after the global recession of 2008/09, but the volume of exports is only now back to 2007 levels. In an economy with unemployment in excess of 25 per cent, there is no crowding out of the export sector.

Import volumes have certainly fallen, very substantially. That might reflect competitiveness gains, and greater opportunities for domestic import-competing tradables producers. But it looks a lot more likely to mostly reflect a severe compression in demand. The collapse in real investment is particularly telling.

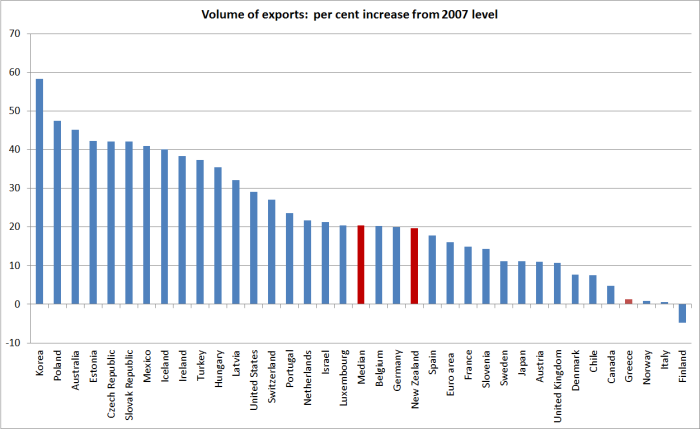

Out of curiosity I also dug out from the OECD data on export volumes for all the OECD countries since 2007. This chart shows export volume growth from the 2007 annual level to the most recent quarter (mostly the March quarter of 2015).

Of the 35 individual countries shown (OECD members, plus Latvia), Greece has had the fourth weakest export volume performance over that period. The result isn’t particularly sensitive to the starting point: I also looked at growth since the 2007-2008 quarterly peak, and Greece was second worst on that. With so much spare capacity, and no room to use domestic macroeconomic policy tools to stimulate demand, Greece needed export growth more than any other country in the group. But it has simply not achieved it – and not even really begun to achieve it.

Who knows what the outcome of the weekend’s meetings in Europe will be. But it looks as if Greece still desperately needs a substantial real exchange rate devaluation. For Greece, resource-switching has not occurred within the euro, despite years of extraordinarily high unemployment. It is hard to see how any of the recent “austerity plans” will materially alter that situation any time soon. Flexible exchange rates tend to make the adjustment easier. They provide no guarantee, but what does staying with the status quo offer economically?

In passing, the New Zealand export performance has not been that impressive – around the median of this group of countries, and not much different from the euro-area countries as a whole (and these aren’t per capita data, and we’ve had stronger population growth than most).

It now looks like the Germans are going to force a Grexit. I can’t help thinking that in the long run this is a good thing because, as far as I can tell, the Euro is a project that has brought misery to millions of people and will continue to do so indefinitely.

LikeLike