I had a look at ten OECD countries/areas whose central banks have since mid-2009 raised their policy interest rates and subsequently lowered them again. I was curious as to how quickly those reversals came, and what else was going on.

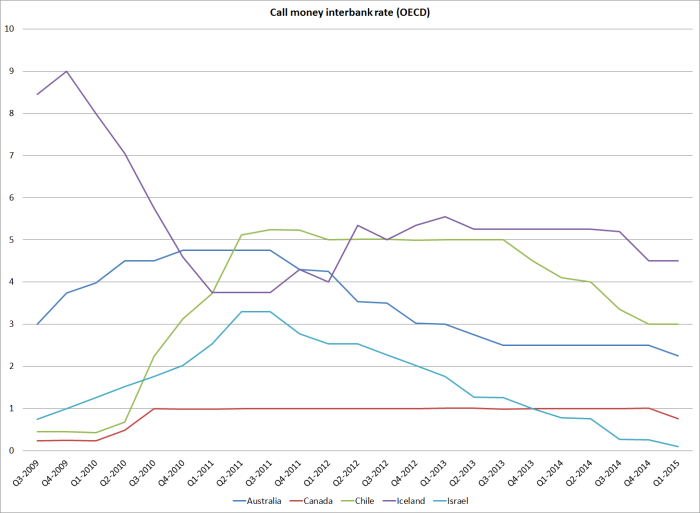

The overnight interest rates for these countries are shown below. Overnight rates aren’t the same as policy rates, but the OECD has these data readily available.

A couple of cases we can fairly quickly set to one side. The Bank of Canada began raising its policy rate in mid 2010, and only in late 2014 did it make a single subsequent cut. Iceland raised rates in 2011, and did not cut again until mid 2014. Given the turbulent circumstances of Iceland, the stability in policy rates is quite surprising.

Australia and Chile both benefited hugely for a time from the late phase in the hard commodities price boom that peaked in 2011. In both cases the increases after the 08/09 crisis seemed pretty well-warranted, and in Chile’s case the peak rate was held for two years before some cuts were put in place. In neither country’s case has inflation been uncomfortably low relative to the target.

I don’t know much about Israel, but the very shortlived nature of the post 2009 peak interest rate, combined with the fact that the policy rate has subsequently been cut to new lows, and that CPI ex food and energy inflation has been running well under 1 per cent for some time suggests a policy mistake.

The Swedish policy mistake has been well-documented by Lars Svensson (and only rather grudgingly accepted by the Stefan Ingves, the Governor of the Riksbank). Both Sweden and Norway will have been affected by the unforeseen severity of the euro crisis, but in Sweden’s case in particular there was a clear misjudgement by the policy committee.

The ECB’s policy tightening in 2011 proved to be extremely shortlived. I’m not aware of anyone who would call it anything other than a mistake. There is probably a variety of factors that influenced the ECB at the time, but they acted too soon, under no (inflation target) pressure, and quickly had to reverse themselves.

Finally, we have the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, the only one of our ten central banks to have reversed itself twice in five years. The 2010 increases took place at a time when a variety of other central banks were raising policy rates. There was some reason to think that the recession was behind us, and that it would be prudent to begin raising rates. I wasn’t involved in the Reserve Bank’s 2010 decisions – I was on secondment at Treasury – but from memory I thought they were sensible moves. As it turned out, by the time the rate increases were being put through the economy was already turning down again, and had a shallow “double-dip recession” The February 2011 earthquake was the catalyst for cutting the OCR again. Initially, it was sold as a pre-emptive step, but we fairly soon realised that the level of interest rates actually needed to be lower even once the initial shock had passed.

And then the Reserve Bank did it again. I’m not going to rehearse the ground I covered this morning, but it is difficult not to put this episode – the increases last year, now needing to be reversed – in the category of a mistake. It is harder to evaluate other countries’ policies, but I would group it with the Swedish and ECB mistakes. Monetary policy mistakes do happen, and they can happen on either side (too tight or too loose). But since 2009 it has been those central banks too eager to anticipate future inflation pressures that have made the mistakes and had to reverse themselves. As a straw in wind, in a country with an unusual governance model, it should be a little troubling that our central bank appears to be the only one to have made the same mistake twice. It brings to mind the line from “The Importance of Being Earnest”:

To lose one parent may be regarded as a misfortune; to lose both looks like carelessness.”

Michael I believe that both committees and single decision makers are capable of making mistakes. Further as I think you acknowledge the governor takes advice from his team and always goes with the consensus or majority view. And also these two mistakes happened with two different governors perhaps suggesting it’s not the person that is the problem.

Isn’t the problem here more with the Bank overall and the group think on neutral interest rates than the single decision maker? I think even with a committee the same outcomes would have occurred. You noted yourself in previous blogs the capture of the external advisors in the whole Bank policy formulation process. How would a committee solve this ? It could make it worse as no one is accountable with a committee.

Also maybe an issue is the lack of clarity about the target as there is a tension sometimes between the inflation target and pricing in wider asset or regional markets ( this is a global problem not just seen in NZ). For decades the Bank has been focused on house prices – often with good reason as these drive consumption investment and wider inflation pressures – but more recently this has morphed into a financial and macro stability concern creating a classic multiple target problem. What to do? Follow the inflation target and ease or try to manage the macro financial stability concerns and tighten? One dart and two boards. The market seems confused – the commentary more or less totally reflected this confusion ahead of the last OCR review. Trying to hit both boards with the same dart will lead to missing both and more of these kinds of misjudgements. There needs to be more clarity on what the OCR should be directed at and what other tools are available for macro financial concerns. Maybe revised legislation would help clarify this and provide the clarity of powers for macro financial policy you think necessary.

The UK MPC/FPC framework could provide a useful model. The MPC is directed to use the Bank rate, QE and FX intervention to achieve price stability whereas the FPC uses the balance sheet, macro financial and prudential tools for financial stability . The FPC need not and generally does not solely feature central bank representation.

LikeLike

Thanks for the comments Kelly

Yes, I agree that both single decision-makers and committees can make mistakes – see eg the Riksbank and the ECB. In general, I have argued for a committee not because I necessarily expect better monetary policy (over 25 years on average ours has not been particularly bad, or good), but on grounds of legitimacy and good public sector management.

And I haven’t gone deeply into the question of why the most recent mistake was made (I was mainly interested in making the case that it was a mistake). I think there has been a variety of factors at work (as there was with the MCI fiasco, altho as I note I doubt an external committee would have allowed that to happen).

It isn’t correct that Governors have always gone with majority views of their advisers, but in this case the recent tightening cycle certainly began that way and (as far as I know) probably ended that way too. So in that sense it is quite right to say that the fault is as much with the Bank collectively as with Graeme personally. As I noted it was an excess predisposition to see inflation risks looming that led to both the 2010 and 2014 mistakes – altho I’d argue there is more culpability for the 2014 mistake simply because of the passage of time, and what other countries were (or in this case, weren’t) doing. But a single decision-maker model, and a Governor (who has many skills but is) without much of a strong recent mon pol/macro (or even NZ economy) background) increases the risks of mistakes being made – of, eg, strong staff priors ending up in policy misjudgements. Think of the MCI – for all his many skills, elements in Don Brash’s style/personality helped make it happen as it did. But all sorts of other factors – some reasonable, some fairly inexcusable, contributed.

Actually, on the external advisers, I’d say that the better ones have not been so much captured, as frustrated. They are plugged into the process at a very technical stage, whereas on a Board (like the RBA’s) they’d be weighing advice that had already gone through the technical processes. I’m arguing for a committee with a majority of outsiders (and for something more like a BOE model, with one committee for each of monetary policy and financial stability).

LikeLike

Isn’t it really a problem of the interaction between fiscal and monetary policy not working. The NZ part of this story is that Bill English and presumably Treasury set out to tighten too soon, whilst the RBNZ was still in stimulation mode. So fiscal tightness meets commodity price drop and we have a problem.

To me the virtue of a quasi independent RBNZ is that it can act fast in an emergency. So in the last crisis the previous governor was able to collapse interest rates before a mass bankruptcy event was created.

Previous to this the previous governor was in just the same quagmire as the present one- namely fiscal tightness demands stimulatory interest rates. The predictable result (in hindsight) was a household debt explosion of $100 billion or thereabouts and rampant Auckland house price inflation as we borrowed big to bid up the price of each other’s houses and build new golf courses. Talk about an own goal. National and the present governor have just repeated the trick. This is clearly stupid.

One solution that occurs to me is a variable tax rate so that the fiscal balance can be more readily adjusted as conditions require without it being seen as a big deal. So in the present situation, if the RBNZ is lowering interest rates the Treasury would be lowering tax rates at the same time. Get it together boys.

LikeLike

Richard

Not sure I agree about the role of fiscal policy (which hasn’t been particularly aggressively contractionary in the last couple of years). I’d also be pretty hesitant about a variable tax rate. On the political rhetoric side, Muldoon wanted to introduce one, and then there was (rightly in my view) an uproar that adjusting tax rates should only be done by Parliament. The house price booms, and debt accumulation, mostly reflect the interaction of two lots of government policies – tight land use planning restrictions, and high target levels of immigration. I’m old-fashioned or conventional enough to think that monetary policy can do a reasonable job of stabilisation so long as other policies aren’t actively set to mess things up. Stable and predictable tax rates have a lot to commend them.

MIchael

LikeLike

To further clarify. You say:

” I’m old-fashioned or conventional enough to think that monetary policy can do a reasonable job of stabilisation so long as other policies aren’t actively set to mess things up.”

My point is there are three things actively set to mess things up – planning, immigration and trying to balance the budget.

LikeLike

I guess I’m coming at from the idea that if you want 2% inflation on average then that implies a 2% fiscal deficit on average. Perhaps that is not so, but it seems plausible enough. Thus a break even budget means interest rates have to be stimulatory enough to cause 2% inflation on their own. This will be via house price inflation in New Zealand given the current and historical settings.

Variable tax rates is one of the tools the US used by giving a social security tax break for 2 years I believe. Just because it is hard and needs some problems solving to get it up and running is no reason to discount the idea. Good ideas often start as messy ones.

LikeLike

Conventional theory would say (perhaps wrongly) that so long as expectations of inflation are around 2% and interest rates are varied around the (changing) Wicksellian “natural” or “neutral” interest rate, inflation will be around target. There shouldn’t be any need for fiscal deficits to bring that about.

Of course, when policy interest rates get to zero, the ground rules change. There probably is more room for active fiscal policy – as with those social security tax changes in the US, or the temporary cut in VAT in the UK in 2008/09. Here we didn’t need any of those things, because our OCR never got below zero. But I guess one could think of a second best argument – if we are going to have so much targeted immigration, maybe we’d have been better off with less fiscal contraction and higher interest rates. But that would have been a recipe for a still-higher exchange rate, further undermining our tradables sector.

LikeLike

As I understand it the RBNZ creates inflation by lowering the OCR so that private credit expands sufficiently to create the desired inflation, ie more $ in circulation. This only works if the private sector is willing to borrow. The government can create inflation by running a deficit, ie injecting money directly into the economy; either by increased spending (if there are productive projects to invest in) or by taxing less. I am drawing on Warren Mosler here.

I am not sure the common worry that the exchange rate will rise with higher interest rates is true, presumably it is the real interest rate after inflation that drives the carry trade. Anyway, the balanced budget, stimulatory interest rate syndrome appears to work primarily to boost Auckland land prices. Would a 1.5% deficit and mildly tighter interest rates to match work better?

My idea is this would set a higher bar for business investment. Instead of finance being seen as widely available and cheap it would be seen as freely available but expensive. So only projects with higher anticipated returns would get funded.

LikeLike

I guess what I am trying to say is the type of inflation created really, really matters. Good inflation presumably comes from profitable export businesses paying higher wages. Poor inflation come from higher Auckland house prices pushing up real estate, banking and legal wages.

LikeLike